Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957): Criterion Blu-ray review

How much does (or should) a filmmaker’s biography affect our experience of watching their movies? For me, I admit, it has something to do with how much that biography is reflected in the work. I had an interesting discussion with the daughter of an old friend not long ago in which we tried to decide why we both could no longer watch Woody Allen movies, but could still watch Roman Polanski movies. What it came down to, we finally agreed, was that many of Allen’s movies embody self-justifications for his objectionable behaviour, while Polanski’s movies address issues which have nothing to do with his objectionable behaviour. It’s still possible to watch his films objectively as creative works while Allen’s seem to be uncomfortably tainted with reminders of what we know (or strongly believe) to be his deeply rooted flaws as a human being.

Elia Kazan is a slightly different case. The behaviour which many perceive to be unforgivable isn’t a matter of sexual crimes; it’s specifically political, and occurred at a time when an entire society was undergoing an almost maniacal upheaval over ideological beliefs. In 1952, Kazan was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and he initially declined to cooperate. This kind of resistance was what led to jail time for some and prolonged blacklisting for many more people in the movie industry – filmmakers such as Jules Dassin, Cy Endfield, Edward Dmytryk and Joseph Losey left the country to build careers elsewhere, while others (particularly writers) remained in the States and worked under pseudonyms, often having their scripts signed by other people to cover the true source.

But called back a second time, Kazan did name names. Even though those he named were already well-known to the Committee – so that it might be argued that he didn’t in fact betray anyone – Kazan was shunned by many of his colleagues and the shadow of his testimony followed him for the rest of his life, eventually garnering a sharply divided response from the audience at the 1999 Oscar ceremony when he received a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Prior to the business with HUAC, Kazan had been an accomplished director with an interest in performance whose work spanned a number of genres. In fact, his work in the theatre, where he was a major advocate for and practitioner of the Actors Studio Method, seemed to supersede any interest in particular themes. In film he moved easily from the sentimental period family drama of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945) to the post-war noir thrillers Boomerang! (1947) and Panic in the Streets (1950), from the rather staid Hollywood attacks on anti-Semitism and racism in Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and Pinky (1950) to his first masterpiece A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), adapted from his successful theatrical production of Tennessee Williams’ play, which established Marlon Brando as a major star while simultaneously blowing holes in the Production Code with its sexual frankness.

Around the time of his dealings with HUAC, Kazan made Viva Zapata! (1952), from a screenplay by John Steinbeck which dealt favourably with a popular uprising against an oppressive government – safely distanced by time and geography from contemporary America. In the immediate wake of the hearings, however, Kazan stumbled with an overtly anti-communist movie called Man on a Tightrope (1953), about circus performers escaping from behind the Iron Curtain, a project which perhaps compounded his moral culpability in the eyes of his critics.

Something more subtle but perhaps as troubling resulted from Kazan’s teaming up in 1954 with writer Budd Schulberg, who himself had recently testified before HUAC. Between them they came up with an intense contemporary drama which manages to give a liberal gloss to the idea of naming names to the authorities. What is most interesting about the Oscar-winning On the Waterfront (eight awards including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Writing) is that the bad guys the hero stands up against are corrupt union bosses. The obvious self-justification of two former Party members concocting a story in which a ruggedly individualistic working man risks his life to expose the insidious influence of unions in American society makes this the most problematic of all Kazan’s movies. It’s impossible not to see it as an unrepentant rebuke of those who criticized him for cooperating with the Committee.

Interestingly, for the next two years Kazan retreated from politics altogether with his adaptation of Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1955), another period family drama, and what may be his most outrageously entertaining movie, Baby Doll (1956), an exuberantly trashy Southern Gothic melodrama written by Tennessee Williams in which a pair of sweaty Southerners lust after the barely legal title character played by a sultry Carroll Baker. The South always had a powerful attraction for Kazan and the region seemed to inspire his best work, from Panic in the Streets through Streetcar to Baby Doll and his final two masterpieces, A Face in the Crowd (1957) and Wild River (1960).

The former, the second collaboration between Kazan and Schulberg, is the director’s most overtly political movie and it’s far more complex and nuanced than On the Waterfront. Perhaps the three intervening years had given both writer and director enough perspective on the events of 1951-52 to deal more openly with the fraught politics of the time. But then the film’s story doesn’t directly address Kazan’s and Schulberg’s own actions, but rather looks at a larger tendency in American political history and the ways in which post-war social and technological developments were exacerbating that tendency.

With various political currents competing for dominance, politicians have long been prone to use emotional appeals rather than reason to win voter support, something which has repeatedly given rise to populist demagoguery. This plays out all across the political spectrum, from Huey Long’s left-leaning populism as Governor of Louisiana and later in the Senate to Joe McCarthy’s rabid Red-baiting in the 1940s and early ’50s and on to the present extremes of Trump and the current Republican Party.

In A Face in the Crowd, Kazan and Schulberg de-emphasize the specific politics in order to foreground the mechanism, although the politicians who get caught up in the Lonesome Rhodes media circus are undoubtedly Right-wing. What the film is about is the toxic effects of crowd-pleasing emotionalism when it permeates the nation’s politics. Everyone touched by the process is ultimately tainted, and the film’s strength lies in how well it shows the almost irresistible appeal to people of having their sense of their own rightness confirmed by someone who seems both genuine and likeable.

This all starts small in a little Arkansas town where local radio personality Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) goes to the local jail to interview a few ordinary folk who have been locked up for petty infractions. On this particular morning, she lucks out: one of those in the lock-up is Larry Rhodes, a drifter with a guitar and a chip on his shoulder. Rhodes is arrogant and abrasive, but when he starts talking he’s mesmerizing, relating folksy anecdotes and singing an extemporaneous song about getting out of jail. The resulting bit on the radio generates enough local interest that Marcia and her uncle, the station owner, offer Rhodes – dubbed by Marcia “Lonesome” when he declines to tell her his real name – a regular job.

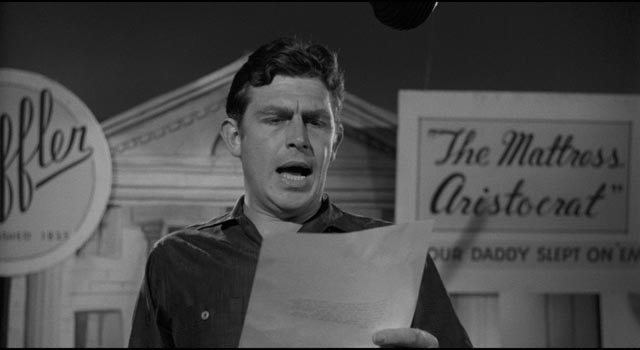

While the entire cast of the film is excellent – with Patricia Neal giving the performance of her career as Marcia – Kazan’s genius is evident in the casting of Andy Griffith as Rhodes in his first movie. Griffith was a singer and comedian, star of the hit Broadway play No Time For Sergeants, when he was cast in the role and his innate folksy charm is used brilliantly. Even though from the first it’s apparent that he harbours a deep anger and bitterness and we can see that the charm is a form of performance he has developed to get through life, we are nonetheless, like the ever-increasing audience within the film, won over for quite a long time.

Although we learn little about his background, the script provides enough information to let us see how this personality has been formed and why he grabs so enthusiastically on to the power he gains. There’s a powerful scene in which Lonesome opens up to Marcia about his past – absent father, mother essentially a prostitute constantly bringing home new “uncles” – which is his way of essentially justifying his assault on a hypocritical society; his accumulation of power is, on a personal level, a way of getting revenge and he makes the most of his opportunities to stick it to those higher up the social ladder. Some of the film’s most satisfying scenes involve Rhodes “speaking truth to power”, though his truth is often a way to openly insult his social betters. And those so insulted have to grin and take it because by this time Lonesome has huge economic power through his faithful radio and television audience.

This is where Kazan and Schulberg bring the social and political forces up to date because, while the figure of Lonesome Rhodes might just be the latest representative of a long line of populist demagogues, the insidious reach of his power is vastly amplified by the ubiquitous new technology of television. In 1957, this might have been seen as yet another attack by Hollywood on the new medium which had been eating away at the movies’ share of the entertainment pie, but in the decades since A Face in the Crowd was made it has taken on a chilling prescience. The confluence of politics, corporate capitalism and the media is all laid out clearly in the film, pointing the way towards what we now live with inescapably. The packaging of phony over-the-counter medicines is no different from the packaging of political candidates, appealing entertainers convincing the public to buy useless and even harmful products for the benefit of an elite determined to control the country for their own purposes …

Those caught up in Lonesome Rhodes’ media juggernaut – particularly Marcia, who feels a proprietary responsibility for his success which is complicated by her fraught romantic involvement with him – at some point all betray their own better nature. While Lonesome’s aw-shucks surface honesty and common sense conceal something darker and more self-serving, too many are willing to go along because at least for a while they personally benefit from his power. (He offends sponsors by insulting their products, but they eat their pride because this tactic actually boosts sales.)

For a while, Lonesome seems to be shaking things up in a positive way. When he finally hits the big time on television, he shocks the system by bringing a Black woman into the studio – a clear violation of norms. She has lost her home in a fire and she and her children are desperate. Although Lonesome asks her to tell her story, she barely gets a few words out before he takes over – what seems at first like an act of generosity takes on a self-serving note. He asks his viewers to contribute a very small sum each to help the woman out, and in no time enough donations have been made for her to build a new house for herself. Lonesome has enabled his viewers to feel good about themselves at very little personal cost, while using the woman as a prop to boost his own image.

Towards the end, the phoniness of this gesture is made even more clear when a desperate Lonesome, now exposed and his power shattered, turns on his entirely black household staff, demanding that they love him and then kicking them out when he realizes that they don’t actually respect him at all.

This is the culmination of the fall Lonesome undergoes after having his contempt for his audience publicly exposed. It takes just one moment – being heard on air expressing that contempt – for all his loyal fans to turn against him, revealing just how unstable the relationship between the demagogue and his supporters really is. They love him because he seems to reflect what they believe about themselves; as soon as they realize he feels superior to them, in fact despises them, their love turns instantly to hate.

If anything, these final moments, with Lonesome losing all his power and being left alone with his own anger and bitterness as his carefully cultivated persona has been stripped away, express an optimism about the possibility of society correcting itself after sliding too far along this delusional path. Today, it’s more difficult to have that kind of faith that reason can reassert itself.

*

A Face in the Crowd wasn’t a commercial success when it was first released, which isn’t difficult to understand. It tried to tell its audience things about themselves which were not pleasant to hear. And yet it’s an enormously entertaining film, one in which every element seems to fall perfectly into place, starting with Schulberg’s acerbic script. The writing is sharp, shot through with humour which gives the drama satirical bite; Kazan directs with a skill which draws every nuance from the writing while giving the actors room to breathe as fully realized characters. Even the smallest supporting roles have depth, giving the film a sense of reality which adds a chilling urgency to its theme.

As mentioned, Patricia Neal is remarkable here, her Marcia a woman of strength and intelligence who herself is nonetheless taken in by Lonesome’s superficial charm until she finally sees him clearly – a knowledge she gains from being personally hurt by him rather than from an objective realization of the danger he poses. Walter Matthau invests the rather thankless role of her friend Mel Miller with a world-weary conviction which suggests an inner life beyond his story function as the educated liberal who sees through Lonesome’s phony act to the dark truth beneath; and Lee Remick, in her first feature, is radiant as the naive girl used and discarded by Lonesome as a means to inflict emotional pain on Marcia.

While Neal provides the film’s emotional and psychological core, Andy Griffith dominates A Face in the Crowd in a star-making performance which was unlike anything else he did in his subsequent career. The appealing side of Lonesome Rhodes became Griffith’s stock-in-trade – as Sheriff Andy Taylor on the long-running Andy Griffith Show and its various spin-offs, and even as high-powered defence lawyer Matlock later in his career – but Kazan dug deep to find something darker and more dangerous inside the actor (in a process which was apparently quite traumatic for Griffith during production). Griffith’s Lonesome Rhodes is one of the great performances of the ’50s, maybe greater than Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire or James Dean in East of Eden.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray features a 4K transfer from the original 35mm negative and the image is excellent, richly detailed with strong contrast and a film-like texture. The mono soundtrack is crisp and clear.

The supplements

Although there’s no commentary, the disk includes more than an hour’s worth of featurettes which delve into Kazan’s and Schulberg’s careers, the genesis of the project and its relationship to the larger political issues. Author Don Briley talks about Kazan and HUAC, the roots of the Lonesome Rhodes character in figures like Will Rogers, Arthur Godfrey and Huey Long, and the film’s prescience about the transformation of politics into product (20:43). Biographer Evan Dalton Smith discusses the impact the role of Lonesome Rhodes had on Andy Griffith personally as well as its effect on the development of his career (19:43). And Facing the Past (29:10) is a documentary from 2005 about the making of the film, including interviews with actors Griffith, Neal, and Anthony Franciosa, writer Schulberg and film scholars Leo Braudy and Jeff Young.

There’s also a trailer (2:19) and a booklet containing an essay by April Wolfe, a piece by Kazan on the importance of writers originally published as the introduction to Schulberg’s script in 1957, and a 1957 profile of Griffith from the New York Times by Gilbert Millstein.

Comments