More from Indicator

Although Indicator releases, on average, only four disks per month, too many of them are desirable acquisitions and my backlog continues to grow. It doesn’t help that I continue to dip into their back catalogue to fill out my collection; a couple of my recent purchases were released in 2017. The titles I’ve viewed in the past month or so are a good indication of the range of interests covered by the company.

Eyes of Laura Mars (Irvin Kershner, 1978)

After making a couple of imaginative low budget movies in the mid-’70s – Dark Star (1974), Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) – John Carpenter’s career really began to take off in 1978. That was the year he hit it big theatrically with Halloween and on television with Someone’s Watching Me. It was also the year one of his early scripts got an expensive studio do-over with a big-name star and a well-known director. Eyes of Laura Mars clearly belongs to the same conceptual world as Halloween and other Carpenter movies, but it would be a while before he himself would have the kind of resources producers Jack H. Harris and Jon Peters poured into this project.

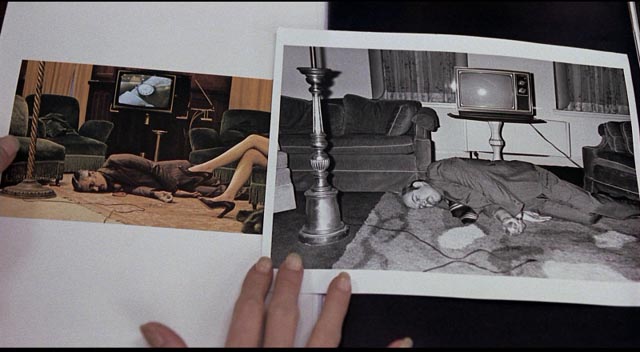

Laura Mars (Faye Dunaway) is a fashion photographer whose fetishistic work is being courted as art in New York. Her images blend eroticism and violence in ways which edge towards pornography (the photos we see in the film were actually shot by Helmut Newton and Rebecca Blake, so they have a kind of sleaze-chic which was familiar at the time). But there’s something more than button-pushing in these shots of lingerie-clad women sprawled in death poses. At the opening of her new gallery show, Laura is approached by a man who seems ambiguously menacing – it turns out he’s a police detective named John Neville (a young Tommy Lee Jones) who informs her that a lot of the pictures are uncannily like crime scene photos from a string of brutal murders. He wants to know what’s behind the coincidence.

In no time, we learn the answer: Laura periodically goes into trances and sees through the eyes of a serial killer. And after the gallery opening, the killer is on to her and begins to stalk her and her friends. As she watches helplessly while people she knows die brutal deaths, she’s drawn closer to the young detective who seems to be the only one willing to believe what’s happening. The reasons for this are pretty obvious before long, although it takes Laura much longer than the average viewer to figure out the killer’s identity.

That identity was changed from Carpenter’s original script at some point during numerous rewrites courtesy of David Zelag Goodman (an interesting figure capable of writing Sam Peckinpah’s masterpiece Straw Dogs [1971] and the camp cheese of Michael Anderson’s Logan’s Run [1976]) and a string of uncredited script doctors (Julian Barry, Mart Crowley, Joan Tewkesbury). This major change was aimed at boosting the woman-in-peril romance aspect of the script, paradoxically making it feel sleazier and more manipulative than Carpenter’s original intention may have been.

Kershner gives it all a slick but impersonal gloss, something he became known for after making a handful of more distinctive and idiosyncratic movies in the 1960s and early ’70s. It’s hard to see the personality of the director who made A Fine Madness (1966) or The Flim-Flam Man (1967) in The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976), The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Never Say Never Again (1983) or Laura Mars. Here, he’s essentially providing a showcase for his star, and Dunaway cranks the emotive dial up to eleven and keeps it there for most of the running time (Laura Mars would make a fine double-bill with Frank Perry’s Mommie Dearest [1981]). But the movie may be more interesting for Tommy Lee Jones’ first big role in a major production – his craggy presence points towards his eventual stature as one of the great character-leads in the business.

Indicator’s disk offers an excellent image, with a detailed transfer showing enough grain to replicate the look of a film from the period – the slickness of the imagery is tempered with a slightly grungy texture which evokes NYC before it was cleaned and polished by corporate interests. There’s a commentary by Kershner carried over from an old DVD edition, a promotional featurette from 1978, an analysis of the script’s evolution from 1999, and a new appreciation by Kat Ellinger. David DeCoteau provides a Trailers From Hell commentary, and there’s a booklet with an essay by Rebecca Nicole Williams (which suggests a connection to the giallo), plus an article about the production by Bruce Williamson originally published in Playboy, and excerpts from contemporary reviews.

*

Torture Garden (Freddie Francis, 1967)

Freddie Francis, one of the great cinematographers, was also a competent director. He obviously enjoyed directing, but one never feels the same depth of commitment to that craft as is always apparent in his cinematography. Given that he was a low-key, charming guy with an impish sense of humour (I was privileged to spend time with him during the production of Dune in Mexico City in 1983), it seems more than a little paradoxical that most of his work as a director was in the horror genre; his amiability makes many of those movies enjoyable but not in the least scary.

As an indication of Francis’ typically matter-of-fact attitude towards his work in movies, the year after he won an Oscar for shooting Jack Cardiff’s Sons and Lovers (1960), and following his superb work on Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (also 1960) and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961), he directed his first feature, The Brain (1962), a low budget adaptation of Curt Siodmak’s venerable 1942 pulp novel Donovan’s Brain. After shooting Reisz’s Night Must Fall (1964), Francis devoted himself full-time to directing until being enticed back to cinematography for David Lynch’s The Elephant Man in 1980, after which he all but gave up directing (his only significant subsequent work being The Doctor and the Devils [1985]) in favour of his original craft.

For five years in the mid-’60s Francis made a string of movies for Hammer, then Amicus.– Jimmy Sangster-scripted psycho-thrillers, one Frankenstein movie, a killer bee movie. Perhaps the most important aspect of this period was his connection with Amicus and the writer Robert Bloch. In particular, he began his work for Amicus by establishing the template for the company’s string of anthology horror movies with Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965). Written by producer Milton Subotsky, who wanted to emulate the classic Ealing omnibus horror Dead of Night (1946), it brings together a group of people who are shown their probable fates by a sinister figure – in this case Dr. Schreck (Peter Cushing) wielding a deck of Tarot cards in a train compartment.

The success of Dr. Terror led fairly quickly to a follow-up, Torture Garden (1967), written by Bloch and based on several of his own short stories. This one is set in a seedy carnival sideshow where Dr. Diabolo (Burgess Meredith) offers a handful of patrons something truly terrifying in a backroom. Those willing to take a chance and pay a small supplementary fee are led past typical freakshow exhibits to a room where the figure of Atropos (Clytie Jessop), one of the Greek Fates, sits poised with her scissors to cut the string of each patron’s life.

As is typical of the genre, the individual stories vary in quality, ranging from the cliched to the silly to the genuinely creepy. A greedy nephew (Michael Bryant) kills his uncle for an inheritance only to find himself tormented by a malevolent cat. An ambitious starlet (Beverly Adams) discovers the dark secret behind longevity in Hollywood. A famous concert pianist (John Standing) finds himself caught between his fiancee and his jealous concert grand piano (no kidding). And in the final and most effective story, obsessed collector Ronald Wyatt (Jack Palance) tries to pressure fellow collector Lancelot Canning (Peter Cushing) to relinquish the most desirable piece of Poe memorabilia in the world. The framing story limps to a conclusion which culminates in the revelation of Dr. Diabolo’s true identity – no surprise there given his name.

Everything about the production exudes a kind of cosy familiarity, each story’s climactic revelation coming as no surprise, but Francis and the cast approach it all with a kind of cheerful enthusiasm. It’s not the best of the Amicus anthologies, but it is entertaining and each story is short enough not to wear out its welcome.

Indicator’s Blu-ray includes both the original 93-minute theatrical version and the 100-minute TV cut which fleshes out a couple of the stories. The image is pleasingly colourful, textured with authentic film grain and strong contrast. Extras include a 77-minute audio interview with Francis from 1995 covering his whole career up to that point; brief interviews with production supervisor Ted Wallis about his work on the film and with Fiona Subotsky about producer Milton Subotsky. Ramsay Campell offers his thoughts on writer Robert Bloch and Kim Newman provides an appreciation of the film. There’s an extensive image gallery, plus the usual substantial booklet.

*

The Wrong Box (Bryan Forbes, 1966)

I first saw Bryan Forbes’ The Wrong Box when it was released in the summer of 1966. I was eleven years old and already steeped in traditions of English comedy. I’d been watching Tony Hancock on television for years, had seen sketches with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore and various movies with Peter Sellers – not to mention having grown up listening to The Goon Show and seeing its TV incarnation as a puppet show with Sellers providing numerous character voices. So at the time, I saw The Wrong Box from that perspective and thought it was very funny. It stuck with me for years, though a long time passed before I had another opportunity to see it.

In the meantime, I read the source novel by Robert Louis Stevenson and his nephew Lloyd Osborne, first published in 1889. The book is a frenetic farce about the pervasive venality of the British and when I read it, it seemed to accord quite well with my memory of the movie. After watching the film again recently on Indicator’s new Blu-ray, I re-read the novel and it was interesting to see the similarities and differences in such sharp contrast. In broad outline, the movie is quite faithful; the narrative is necessarily simplified – the book has a far more complicated storyline, loaded with digressions and tangential subplots – but more importantly a number of characters are quite radically altered.

The story hinges on a tontine – a financial scheme invented in 17th Century Italy, in which a group of people put in money which will eventually be inherited by the last surviving member of the group. In the opening scene, a group of fathers invest on behalf of their young sons. In a quick montage, we see one after another dying off in various (often stupid) ways, eventually leaving only two aging brothers, the dyspeptic and apoplectic Masterman Finsbury (John Mills) and the uber-pedant Joseph Finsbury (Ralph Richardson). Joseph has a pair of nephews, Morris (Peter Cook) and John (Dudley Moore), who virtually stifle him with excessive concern rooted in their desire to inherit all the money themselves. Also in the house is Joseph’s ward, Julia (Nanette Newman).

Masterman has a son, Michael (Michael Caine), who has romantic feelings for Julia. Unlike Morris and John, Michael and Julia don’t have any particular interest in the money.

Because Michael refuses to allow the two brothers to see the bed-ridden Masterman, they suspect the old man is already dead and that Michael is trying to cheat them. When a train crash apparently kills Joseph, Morris and John are determined to cover up the death until they can prove that Masterman is already dead. The wrong box of the title refers to a critical mix-up in which the crate containing the corpse is confused with one containing a hideous classical statue.

Confusion, missed connections, misunderstandings and deceptions abound, leading to a chase through Victorian London in horse-drawn carriages, which ends in a cemetery where everything is eventually untangled. Along the way, romance blooms between Michael and Julia, Morris and John sink deeper into criminal schemes, and estranged brothers Masterman and Joseph are reunited.

The book is much darker than the movie and this is the biggest change wrought by co-writers Larry Gelbert (best known for the TV version of MASH) and Burt Shevelove. On screen, The Wrong Box becomes a more conventional farce at the centre of which is a romance between a pair of sweetly naive characters. In the book, Julia is a lot smarter and tougher and Michael is as bad as the cousins when it comes to concocting potentially profitable schemes. In fact, Michael rather gleefully cooks up complications only partly necessitated by the central plot which make life difficult for friends and acquaintances – he often does it just for the hell of it, for his own amusement, to puncture someone else’s pretensions.

The novel is rich and dark, written with seemingly inexhaustible wit; even more than Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Wrong Box punctures the deeply embedded hypocrisy of Victorian society. Beneath the humour – and it’s a very funny book – runs a deep vein of bitter satire. In comparison, Forbes’ movie is a confection, bright and charming even if it does revolve around a dead body which gets shunted around England with callous disregard for the dead man’s dignity. That said, the film is nonetheless entertaining, with some very fine character comedy from its large cast, quite firmly rooted in its particular moment – a period film in two distinct senses: not only is its story set in the 19th Century, its style and tone mark the end of an age of British comedy best exemplified by Ealing Studios in the 1950s. On its release, The Wrong Box already seemed old-fashioned in the context of the Swinging Sixties – just two years earlier, Richard Lester and The Beatles had invented a more disruptive form of contemporary comedy with A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

Needless to say, the film looks beautiful on the Blu-ray, with Gerry Turpin’s photography lush and colourful. Extras include a lengthy audio interview with director Forbes, a commentary track with Josephine Botting and Vic Pratt, interviews with Nanette Newman, assistant editor Willy Kemplen and second assistant director Hugh Harlow. Plus, of course, an image gallery, trailer and booklet.

*

A Dandy in Aspic (Anthony Mann, 1968)

I’ve always enjoyed the darker, more cynical spy movies which came along quickly on the heels of James Bond’s success in the early ’60s. Some of these went for a greater sense of realism, though one of the greatest – Sidney J. Furie’s The Ipcress File (1965) – has a slightly science-fictional central conceit. Harry Palmer (Michael Caine), an insolent working-class spy who seems to have as little respect for his bosses as he does for his opponents on the other side, is a more interesting character than the smugly self-assured Bond. The major counterweight to Bond, though, came from adaptations of novels by John le Carre – Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and Sidney Lumet’s The Deadly Affair (1967), and later the excellent television adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) – but by 1968 these gritty counter-Bond’s had become so familiar to audiences that they were already leaning towards self-parody. Just look at the quick progression of Harry Palmer from The Ipcress File to Guy Hamilton’s Funeral in Berlin (1966) to Ken Russell’s Billion-Dollar Brain (1967); in three short years the cynicism had become slapstick, the grim realism of Hamilton’s film turning into cartoonish comedy in Russell’s. (Don’t get me wrong – I like all three Palmer movies, each for its own distinct qualities – but the rapid transformation of the genre couldn’t be more clearly seen than through this trilogy.)

With audiences (and critics) already losing interest, Anthony Mann’s A Dandy in Aspic (1968) came along at an inauspicious time. It didn’t help that writer Derek Marlowe had given the story an obscure title or that Mann died of a heart attack before shooting was completed – star Laurence Harvey finished the film. But the weak response was probably mostly due to a feeling that there wasn’t much new here. Yet, as with so many movies, once enough time has passed to separate it from its original context, it’s easier to see A Dandy in Aspic on its own terms and as an example of the genre it’s pretty good.

Like the le Carre films, it’s steeped in a pall of exhaustion. In the world of international espionage – a world in which identities are endlessly subsumed beneath performances whose purpose is deception – operatives burn out and long for a chance to emerge and just be themselves. But after years of playing those roles, it’s difficult to remember who they really are – they become the characters their work forces them to play and at the point of rejecting those characters they all too often find that they have become empty shells, plagued by vague memories of a life before.

For an actor, this can be a hard thing to play, weary cynicism risking the loss of audience sympathy. Richard Burton in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is a grey, sagging figure with barely enough energy to keep going. But Burton had a history, a larger than life stature which he could lean on in order to fill that on-screen space. Laurence Harvey, however, was never a terribly expressive performer, frequently accused of being wooden. But that in-turned stiffness was something he could use to good effect in the right role – like Raymond Shaw in John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962), a man already hollowed out by his devouring mother long before the Chinese scrubbed his brain and transformed him into a weapon under their control; the tragedy of Raymond is fully revealed only when some small part of the man who might have been surfaces and he turns against his handlers and his mother to assert himself at last.

That same opaque facade serves Harvey well in A Dandy in Aspic. Alexander Eberlin is a man whose work has forced him to disappear into a role for years. He works for British intelligence, tasked with killing enemy agents. Now someone is killing British agents in Europe. The culprit is believed to be a Russian agent named Krasnevin. Although no one knows who this shadowy figure is, Eberlin is sent to Berlin to find and assassinate him. This poses a serious problem – in fact, an existential dilemma – because Eberlin himself is Krasnevin, a double-agent planted by the Russians.

In Berlin, caught in an impossible situation, Eberlin passes time in seemingly meaningless activities. He meets and becomes involved with a perky photographer (Mia Farrow), who briefly allows him the illusion of a normal relationship. But he’s being shadowed by another agent, Gatiss (Tom Courtenay), who despises him and has been sent to oversee the search for Krasnevin. Eberlin desperately tries to enter East Berlin, wanting nothing more than to go home, to end all the deception and become himself again. But his handlers, led by Sobakevich (Lionel Stander), consider him too valuable where he is.

Needless to say, there are deeper levels of deception and betrayal; by the end, it’s clear that the British already know Kresnavin’s true identity, that Eberlin has been sent on this mission to root out other Soviet agents and expose them for assassination before he himself is disposed of. It’s all been a sordid and pointless game, each side caught in a mutual spiral of escalating violence which leads nowhere.

Whatever the real world values of espionage might be, in the literary and cinematic universe it always seems that any information gained or lost is of no lasting value; the spies and the bureaucrats who run them are trapped in convoluted schemes engendered by their own petty ambitions and paranoia. It’s a world in which morality and personal desires are a hindrance, but in which there is little to offer in their place.

A Dandy in Aspic reflects Anthony Mann’s long-standing interest in moral dilemmas, running from his films noirs in the ’40s through his westerns in the ’50s. He got somewhat sidetracked by Sam Bronston in the early ’60s, when he turned his hand to large-scale historical epics – after famously being fired from Spartacus (1960) by Kirk Douglas, Mann directed El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). His strengths lay in taking familiar genres and infusing them with a personal view of complex characters and their relationship to social and natural environments. After the epics, he moved back in that direction with the fairly routine war movie The Heroes of Telemark (1965) and finally A Dandy in Aspic.

This last film was shot almost entirely on location in London and Berlin and this grounds the story in a vivid world where familiar urban landscapes become fraught with danger. If A Dandy in Aspic doesn’t add anything distinctly new to the spy genre, it nonetheless presents its story with conviction. And as an added bonus, it features a cast of great character actors – Harry Andrews, Lionel Stander, Per Oscarsson, John Bird, Norman Bird, Geoffrey Bayldon, James Cossins, even Peter Cook and Calvin Lockhart – who provide excellent support for Harvey, Courtenay and Farrow.

That said, the image on the Blu-ray is probably the weakest I’ve seen on an Indicator release; it’s not the somewhat murky texture that’s troubling, but the excessive and distracting edge enhancement which in many scenes produces a bright white halo around characters and objects. Coming from this company, it’s quite disappointing.

The extras include an audio interview with cinematographer Christopher Challis and a commentary from Samm Deighan. There’s a brief featurette with several members of the crew, focusing on the impact of Mann’s death during production; a longer one about the distinctive title design with Michael Graham Smith and puppeteer Ronnie Le Drew. Richard Combs offers an appreciation of Mann. In addition, there’s a short promo piece about the shoot in Berlin, a brief featurette about the locations in England and Germany, an image gallery, trailer and booklet.

Comments