Recent Brit disks

I probably should have planned ahead and done something special for this week’s post – it’s my 600th since I began this blog in October 2010. Back then, I had no idea how long I’d be able to keep it up, but with at least one post per week over almost nine years, I now can’t imagine stopping. It’s become a compulsion, demanding that I find something to write about even when I don’t really feel like it. The next couple of months are going to be particularly difficult because in a couple of weeks I’ll be undergoing surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff in my right shoulder. Not only is it going to be a problem doing routine things with only one usable hand, I have no idea how well I’ll be able to type with just my left hand because I’m a life-long two-finger typist. It’ll be at least a month before I begin to regain use of my right hand, so there may be a few weeks in which I’ll be posting much briefer comments than I’ve become accustomed to. But I’ll definitely still try to add something once a week.

*

In the past few months my resolve has slipped and I’ve binge-ordered from several sources in England – directly from Indicator, Arrow and Eureka and also, for the first time in a while, from Amazon UK. (I’d been avoiding the latter because changes in their shipping policies had increased the cost of ordering from them, but deep down I knew I’d eventually crack and accept the added expense – partly because ordering directly from the BFI is even more prohibitively expensive.) With several new piles of disks waiting on the coffee table, I’ve been dipping randomly into these new acquisitions.

Stranger in the House (Pierre Rouve, 1967)

One of the oddest is a new release from the BFI’s Flipside sub-label, a movie I’d never even heard of even though it has a prominent cast in James Mason (a favourite), Geraldine Chaplin and Bobby Darin. Stranger in the House (1967) was the sole directing credit of Pierre Jouve, who the previous year had executive-produced Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up. Jouve was obviously no Antonioni, but the influence of that association is apparent at times in this film. Visually stylized (its flashback sequences are shot as black-and-white in colour, with sets painted blindingly white), it tries to replicate the hip tone of Blow-Up’s hedonistic young characters, but more often succumbs to the curse of an older filmmaker trying to fake youth – echoing some of the more ridiculous juvenile delinquent movies of the ’50s. (As Jonathan Rigby points out in his booklet essay, the scene of the young characters running loose on an empty ship looks more like something from a Cliff Richard musical than a threat to the bourgeois status quo.)

Jouve’s script was based on a non-Maigret novel by Georges Simenon (previously adapted as Les inconnus dans la maison in 1942, scripted by Henri-Georges Clouzot and starring Raimu) and beneath the stylistic missteps there’s an interestingly cynical story about social and legal hypocrisy. Mason plays John Sawyer, a bitter, washed-up barrister who haunts his Winchester house like a ghost, perpetually drunk and emotionally distant from his daughter Angela (Chaplin). He has lost all respect for the legal profession – and is plagued by guilt – because his clumsy handling of a murder case ended up with his client being hanged. Although they share the rambling old house, Sawyer and Angela are strangers to one another – providing one of the title’s meanings.

The other, more literal, meaning derives from the presence in an attic room of Barney Teale (Darin), a sailor Angela and her friends have discovered on that empty ship and provided with a hiding place in a derelict movie theatre owned by one of their fathers. Teale is a demonic figure, pushing and provoking the callow children of rich parents with his emotional and sexual taunts. When he goes too far, a fight leaves him injured and Angela sneaks him into the attic room, unknown to Sawyer. Then one night someone enters the house and kills the man in the attic.

Evidence points towards Angela’s boyfriend Jo (Paul Bertoya), an outsider who doesn’t really fit in with the group, being a Greek immigrant whose mother works in a laundry. Angela pleads with Sawyer to take on the case, to defend Jo against the charge of murder; although he initially refuses because the whole process disgusts him, he finally agrees. But his conduct in court at the preliminary proceedings makes it look as if they’re heading towards the same conclusion as the trial which turned Sawyer into an embittered alcoholic. He can hardly muster the energy to pay attention to what’s going on, doesn’t bother to ask questions or call witnesses, drinks whisky from a flask and mutters insults towards the magistrate. It seems almost as if he’s taking the opportunity to torture Angela in revenge for being betrayed (in his view) by her unfaithful mother.

Rouve makes little effort to make any of this feel realistic; it’s all symbolic drama expressing contempt for a system which has virtually nothing to do with seeking the truth. With the court proceedings collapsing, Sawyer solves the case elsewhere – at a society party thrown by his sister and brother-in-law, at which Sawyer makes a spectacle of himself with his open contempt for everything these people represent before confronting the person he (somehow) knows is the actual killer. The law has nothing to do with any of this – rather, it’s about facing moral failings and owning up to personal culpability. It’s enough for Sawyer that he gets the killer to admit what he’s done.

I can’t say that Stranger in the House is a good movie, but it’s definitely an interesting artifact, and Mason is in fine form as a tortured alcoholic for whom the world has simply become unbearable. The cast is generally very fine, though Darin in one of his last screen appearances (other than some television work, he only did two more features) gives a mannered performance which becomes irritating at times. Ian Ogilvy plays a crucial role between his appearances in the first and second features of Michael Reeves, the low-budget horrors She Beast (1966) and The Sorcerers (1967). In addition to the cast, the film’s chief interest is some fine location photography by Kenneth Higgins, who worked on a number of notable movies in the ’60s, from Ken Russell’s debut, French Dressing (1964), to John Schlesinger’s Darling (1965), Silvio Narizzano’s Georgy Girl (1966) and John Dexter’s The Virgin Soldiers (1969) – the latter two recently released on disk by Indicator. Rouve, like Antonioni, found some less familiar locations to shoot the exteriors – in this case in Winchester and around the docks in Southampton. Echoing the presence of The Yardbirds in Blow-Up, the theme song (“Ain’t That So”) is performed by Eric Burdon and the Animals.

The BFI has released the film in a dual-format edition, with a commentary by Vic Pratt and William Fowler, a lengthy audio interview with Mason from 1981, a couple of brief silent clips showing Southampton in the early 1900s, a British Transport documentary about the city’s docks (1964), a two-minute commercial for coffee exploiting the hip image of Swinging London, and a short film directed by photographer David Bailey: G.G. Passion (1966, 25 minutes), about a pop star being consumed by the insidious Capitalist forces behind the music industry. To a genre fan, it’s perhaps most interesting for its glimpses of a 16-year-old Caroline Munro at the very beginning of her career.

*

Berserk (Jim O’Connolly, 1967)

Producer Herman Cohen is probably best known for a string of very cheap horror movies he put out in the late 1950s – I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (both 1957) and How to Make a Monster (1958). At the end of the decade, he began making cheap horror movies in England, taking advantage of tax incentives which helped to stretch the budgets. The best known of these were Arthur Crabtree’s Horrors of the Black Museum (1959, co-written by the producer) and James Hill’s Sherlock Holmes vs Jack the Ripper tale A Study in Terror (1965).

Somehow, in 1967, Cohen managed to convince Joan Crawford to go to England and star in a creaky murder mystery set in a circus. Berserk (1967) was the star’s second-last feature (she ended her career with another Cohen production, Freddie Francis’ ridiculous missing-link movie Trog [1970]). She plays the show’s unscrupulous owner, Monica Rivers, who enthusiastically cashes in on the publicity when performers start getting knocked off by an unknown killer. When the high-wire star falls to his death (in the opening scene), a mysterious American shows up to offer his services; Frank Hawkins (Ty Hardin, star of the TV western series Bronco [1958-62]) has a dark secret and punches out anyone who alludes to it. Although Hardin was little more than half Crawford’s age, the pair soon embark on a sexual relationship, though he gets a shock when Monica’s surprisingly mature teenage daughter Angela (Judy Geeson, fresh from James Clavell’s To Sir, With Love) turns up, having been kicked out of school for bad behaviour.

In between flinging around red herrings as Detective Superintendent Brooks (Robert Hardy) questions circus staff about the murders, director Jim O’Connolly (The Valley of Gwangi [1969], Tower of Evil [1972]) spends a lot of time making the most of Cohen’s deal with the Billy Smart Circus to boost production value. What story there is gets padded out with entire acts performed in front of actual patrons – sequences which have nothing to do with any of the story’s characters. In a way, this documentary record of the circus turns out to be the most interesting thing in the movie; the display of animals in various acts – elephants, lions, dogs – is tawdry and sad, a form of entertainment we no longer find acceptable.

To add to the sense of bifurcation between these sequences and the mystery story, the fictional characters include an assortment of sideshow attractions who raise memories of Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), although they don’t seem to fit anywhere into the repertoire of this particular circus – a dwarf, a strong man, a human skeleton and a bearded lady. They help to give the movie a kind of random, thrown-together feel which climaxes with the final revelation of the killer’s identity, which comes out of nowhere and seems arbitrary (and inexplicable if you try to piece together the original sequence of events).

Despite the movie’s threadbare qualities, Crawford gives a genuinely committed performance, proving herself every bit the movie star by not condescending to the material. She’s given solid support by a mostly English cast of character actors – the always dependable Michael Gough, who worked on quite a few projects for Cohen; Hardy, Geeson, Geoffrey Keen, Sidney Tafler and Diana Dors.

Cinematographer Desmond Dickinson makes the most of the seedy setting, frequently lighting Crawford in a flattering way, although in one sequence between Monica and Hawkins he manages to make her look rather old and sinister. Dickinson was just beginning the fifth decade of a career which began in 1927 and included among its highlights several films directed by Anthony Asquith and, most significantly, Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948). From the late ’50s to his retirement in 1975, he shot a lot of low budget horror movies, most notably in addition to his work for Cohen John Llewellyn Moxey’s The City of the Dead (1960)

Indicator’s Blu-ray offers a solid transfer with authentic looking film texture and their usual substantial selection of extras, including a short interview with Crawford from 1956, an audio commentary by Lee Gambin and Eloise Ross, an appreciation of Crawford by critic Pamela Hutchinson, an account of the production by Jonathan Rigby, a reminiscence of Cohen by business partner Didier Chatelain, and an introduction to the movie by Tom Baker recorded for its original VHS release (accompanied by outtakes from the recording session). The fat booklet includes an essay by Josephine Botting; archival interviews and articles on Cohen, Crawford and Diana Dors; and excerpts from contemporary reviews.

*

The Man Who Could Cheat Death (Terence Fisher, 1959)

Terence Fisher launched Hammer Films’ Gothic horror tradition with The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957 and guaranteed its success with his 1958 follow-up, Dracula. While the studio continued a more wide-ranging slate, with thrillers, war films, period adventures and comedies, those two iconic monsters pretty much defined Hammer throughout the 1960s. But as early as 1959, Fisher and his employers were looking for ways to expand the genre. That was the year Fisher made The Stranglers of Bombay (history as horror), The Hound of the Baskervilles (detective story as horror), The Mummy (well, you get the point) and, what remains a lesser known effort, The Man Who Could Cheat Death.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death was an attempt to break away from the studio’s ties to the classic Universal monsters, but it’s less successful than Fisher’s The Gorgon (1966) or John Gilling’s The Reptile (1966). Based on a 1939 play by Barré Lyndon called The Man in Half-Moon Street, previously filmed by Paramount in 1945 (dir. Ralph Murphy), the story bears a vague resemblance to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, but reaches farther back to the legend of the 18th Century alchemist St. Germain who supposedly discovered the secret of immortality. (This source links Lyndon’s play closely to Richard Matheson’s script for The Night Strangler [1973].)

Immortality depends on access to glands and secretions which, for freshness, require living donors. So every ten years Dr. Georges Bonnet (Anton Diffring) has to commit murder to remain young. The mechanics are a bit vague – his old colleague Dr. Ludwig Weiss (Arnold Marlé) is needed to perform the operation, but apparently has never twigged to the fact that the glands he transplants are the product of murder. This year (in the 1890s) Bonnet is getting desperate; time is running out and he needs to take stronger and more frequent doses of his magic potion to stave off catastrophic aging as he waits for his old friend to arrive in Paris. When Weiss finally does appear, things get worse – the old man has had a stroke and is incapable of performing the operation.

Needing a new pair of hands, Bonnet uses Weiss’ reputation to persuade Dr. Pierre Gerrard (Christopher Lee) to do the procedure. Gerrard doesn’t seem to like Bonnet, at least partly because of jealousy over his friend Janine Du Bois (Hazel Court)’s attraction to Bonnet. Juggling his relationship with Janine, his physical disintegration (and a couple of murders resulting from it) and Gerrard’s reluctance and disdain, Bonnet finds himself facing the horrors of age and death, his desperation making him violently insane.

When the production was being planned, Peter Cushing was originally cast as Bonnet, continuing the on-screen association between him and Lee as the defining faces of Hammer horror, but he balked a few days before shooting began, tired already of the prospect of being typecast as the studio’s go-to mad scientist. The German actor Anton Diffring was quickly hired, not least because he had recently played the part in a television production of the play. This no doubt altered the tone of the movie; Diffring lacked Cushing’s ability to be both cruel and appealing, making it difficult to swallow Janine’s passion for the icy doctor – not that the stiffly upright Gerrard is any more desirable as a romantic lead.

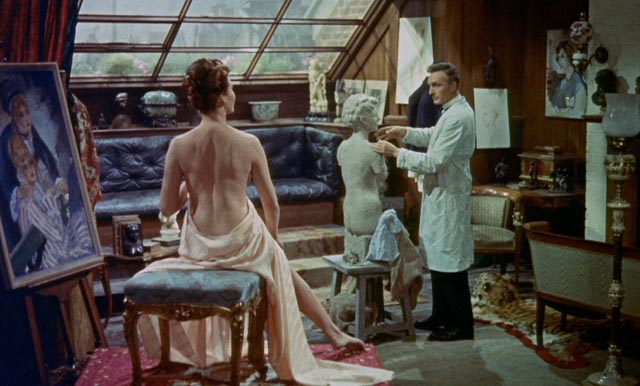

Although the studio’s above-budget production standards are evident in Bernard Robinson’s set designs and Jack Asher’s photography, The Man Who Could Cheat Death is further hampered by Jimmy Sangster’s script (another reason Cushing withdrew). Sangster does nothing to open the play up, limiting the action to four rooms – Bonnet’s sculpture studio, his office, his laboratory, and the cellar where he keeps the busts he has made over the years of the women he’s killed for their glands. The only time we get out of these rooms is during the title sequence in which Bonnet stalks an old man through foggy alleys to harvest the gland he needs for what he thinks will be an imminent operation (the gland becomes useless sitting in its jar of preservative for days while he waits for Dr. Weiss to show up).

The film does have some limited appeal – the absurdity of Bonnet’s safe which contains a bubbling jar of fluorescent green potion, the hammy sincerity of Arnold Marlé as Weiss, and most particularly Hazel Court’s presence as Janine – but it remains a minor work for both Hammer and Fisher.

Needless to say, Eureka’s dual-format edition offers an excellent video transfer on the region B Blu-ray, with rich colours and pleasing film grain. There are a pair of interviews – from Kim Newman and Jonathan Rigby – which fill in details about the production (with some duplication). There’s also a Kino region A Blu-ray which has the same features plus a commentary by Troy Howarth.

Comments

I like The Man Who Could Cheat Death quite a bit. I only saw it in the last couple of years, at least as far as I remember. I’ll have to keep an eye out for Berserk.

I have developed an obsession for Network’s The British Film series. There are over 300 films in the series, much of it from StudioCanal’s archives. That’s a company with a interesting and large film library. They bought up the archives of several British film companies, like Ealing Studios and Anglo Amalgamated. Worth reading the Wikipedia page on it.

The films aren’t the big hits people here in the US might have seen. Smaller pictures from the 40s to the 60s with few big name actors that are lucky to be on DVD at all. Some of these pictures are turning up on home video for the very first time. I doubt they would ever come out on DVD here in the US, maybe streaming seems very unlikely. I can’t see hardly anyone watching them in the US.

I just finished watching The Key Man with Canadian actor Lee Patterson (I never heard of him before) as a radio reporter who’s got hold of an interesting and deadly story. That’s one from Merton Park Studios. Never heard of them either.

So far I’ve seen about 15 films from the collection and haven’t been disappointed with them. I’ve got a cache of 5 to watch and more on the way. I’m bringing Invasion to Friday Night Movie night, it’s a 1965 SF film with an original story by Robert Holmes. Some sort of alien invasion story with Edward Judd and Yoko Tani.

They’re fairly cheap on Amazon UK, 3-5 pounds for many of them, I usually add one or two to a TV Box set order. I usually order something every week or so. My only complaint about Amazon UK is they really pack the DVDs into shitty folded boxes that have little or no external support. I usually keep the orders small and don’t sweat the postage. It’s better than having to received damaged cases or discs. If it’s ordered from Amazon UK you can usually talk them into letting you toss the return for a refund or replacement because the postage is so high for the return. Much much higher than they charge at Amazon UK’s end. I once packed up a 4 disc set that was trashed by the mail sorting machines and the return postage was $21. Amazon had charged about 3 pounds postage. That’s a big difference. Oh, well!

Yeah, I’ve got a few of those Network disks (DVD and Blu-ray). I’ve been a bit selective because there are so many of them, and a lot are fairly generic genre movies. If I had the time and money, I’d probably buy more as they remind me of the kind of B movies I saw as a kid in England. Network also releases a lot of old British TV shows.