Twilight Time spies

in Michael Anderson’s The Quiller Memorandum (1966)

Movies inevitably change with the times. At the height of the Cold War, the best spy movies were complex moral puzzles, while today espionage is more often an excuse for stringing together action scenes. Although James Bond became a cultural icon in the 1960s, it’s easy to forget that he had very little to do with the then current real world situation – his nemeses were most often megalomaniacal criminals rather than the monolithic bureaucracies of political opponents. Perhaps that’s the main reason he has endured; he was never really tied to changing social and political currents. As often as not, his descendants (Ethan Hunt of the Mission: Impossible franchise, for instance) also face cartoonish criminals, politics supplanted by commercial interests.

The great (and even not-so-great) spy stories of the ’60s are dramas of moral confusion, populated by characters who frequently find themselves engaged in actions which violate their own sense of honour and decency in support of governments which may well be no better than their enemies. John le Carre was the master of this genre and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (dir. Martin Ritt, 1965) the key cinematic text. Sidney Lumet’s The Deadly Affair (1967) and Anthony Mann’s A Dandy in Aspic (1968) closely followed this model, while the Harry Palmer movies bridged the gap between Bond and le Carre, applying the latter’s gritty realism to the former’s more fantastical narrative tropes.

The Quiller Memorandum (Michael Anderson, 1966)

Among the authors who followed in le Carre’s footsteps, one of the most prolific was Elleston Trevor (author of The Flight of the Phoenix), who wrote a long series of novels about an agent named Quiller under the pseudonym Adam Hall. Quiller is a British agent whose specialized knowledge acquired during and after the War has made him an expert in the threat of a resurgent Nazism. The first book in the series, The Berlin Memorandum (a best-seller when published in 1965), was made into a movie in 1966 with a number of changes, which apparently made Trevor unhappy.

Renamed The Quiller Memorandum, the script was written by none other than Harold Pinter, his third adaptation for the screen of another writer’s work (following The Servant, 1963, and The Pumpkin Eater, 1964). I haven’t read Hall’s novel, so can’t say what all the changes were, but the Pinter touch is quite apparent in the many oblique, at times cryptic, conversations and seemingly non-sequitur details scattered throughout the movie.

The story involves an operation to expose a cabal of Neo-Nazis operating in Berlin. After an agent on their trail is murdered, the British somehow call in the services of an American who has been operating in the Middle and Far East. Quiller doesn’t seem to like the British and sets off to work alone while his handlers struggle to keep up. His investigation leads him to a teacher into whose life he insinuates himself. It’s unclear whether he believes she has any useful information or just wants to seduce her. Either way, she gets drawn into an increasingly dangerous situation as his actions attract the attention of the Nazis.

While he makes himself a target, he also seems to become a useful tool for the Nazis, who having revealed themselves to him fail to kill him – possibly deliberately so that he in turn will lead them to his handlers. It all remains somewhat vague, neither Quiller’s nor the villains’ plans ever clearly defined – despite a few murders and a bit of torture, the stakes never seem very high.

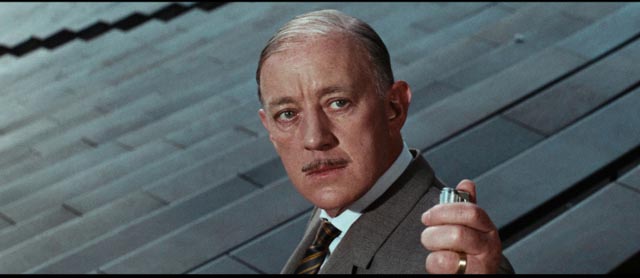

There seem to be a few reasons for this. You get the feeling that Pinter simply wasn’t particularly interested in the mechanics of the plot, instead amusing himself with tangential character details – Alec Guinness’ prissy handler; Max Von Sydow’s suavely sadistic Nazi; George Sanders’ and Robert Flemyng’s insufferably upper class intelligence bureaucrats more concerned with the gradations in their own status than with the lives of agents they send into harm’s way.

Second, although Michael Anderson was often an efficient director, his work seldom displayed a distinctive personality. Individual scenes are well-staged, performances for the most part interesting (though this may be due as much to the combination of a talented cast with Pinter’s writing as it is to the direction), but there isn’t a lot of tension in the film.

Which brings me to what may be the movie’s key weakness. Quiller is played by George Segal, who no matter what the dramatic situation always seems to be playing light comedy. He lacks the dangerous edge of Michael Caine (as Harry Palmer) or Sean Connery (as Bond), even when being tortured by Nazis. Segal’s performance sets the tone for the whole film, a man who doesn’t take anything particularly seriously, who faces danger with a slight mocking grin. As a result, the film seems tonally off-kilter. In fact, at times Segal becomes irritatingly off-putting – most notably in his scenes with Senta Berger, who plays a school teacher with ambiguous allegiances. In these scenes, Quiller comes across as a sexual harasser and audience sympathy leans towards the woman who may or may not be a Nazi herself.

Segal’s presence was no doubt a commercial decision – the character was made an American to supposedly broaden the film’s appeal (he’s a British agent in the book; the script awkwardly drags an American agent in to work for the British on this particular case), and Segal had just appeared in the very successful Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, though ironically as a weak character completely chewed up by the monumentally destructive George and Martha.

What the film does have, in addition to an otherwise fine cast, is excellent location photography shot in West Berlin by Erwin Hillier, who among many other films had shot two of Michael Powell’s finest, A Canterbury Tale (1944) and I Know Where I’m Going (1945), as well as Anderson’s own Operation Crossbow (1965) and Alexander Mackendrick’s Sammy Going South (1963).

The Twilight Time Blu-ray has a strong image, with solid colours and contrast. John Barry’s score gets an isolated track, and there’s an informative commentary from Eddy Friedfeld and Lee Pfeiffer, ported over from a 2006 DVD edition.

*

in Fred Schepisi’s The Russia House (1990)

The Russia House (Fred Schepisi, 1990)

By the late 1980s, the dynamics of the Cold War had changed. U.S. domestic politics had never recovered from Nixon and Watergate, and American activity in the Third World under Reagan had been exposed as criminally corrupt with the Iran-Contra affair, the absurd invasions of Grenada and Panama, the arming of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq with chemical weapons, and on and on. Meanwhile, the U.S.S.R. was mired in its long and misguided occupation of Afghanistan (where the U.S. was arming the Taliban as freedom fighters), while the Soviet economy was collapsing under the weight of keeping up the arms race. The facade of moral superiority which had sustained the West through much of the Cold War had been crumbling for years and, at the end of the decade, John le Carre wrote a novel which focused on ordinary people trying to survive the oppressive manipulations of espionage agencies struggling to maintain and assert their relevance as the world around them rapidly changed.

The Russia House, adapted in 1990 with a script by Tom Stoppard and directed by Fred Schepisi, is set in the final years of Glasnost, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet empire, and the film adaptation was produced the year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, with extensive location shooting in Moscow and Leningrad/Saint Petersburg. The photography of Ian Baker makes the most of this opportunity, giving weight to a story which uses unpolitical characters as a bridge between East and West, reflecting a human commonality shared by ordinary people who have been forcibly separated by antagonistic systems of political and social control.

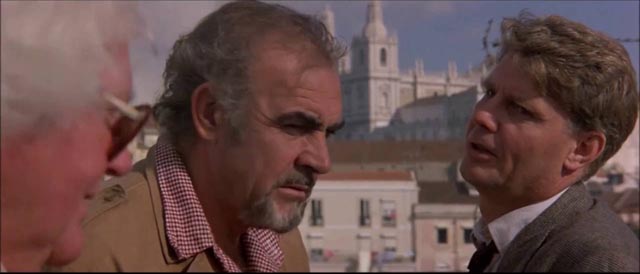

The protagonist is a disillusioned, alcoholic British publisher with a love of Russian culture. Bartholomew “Barley” Scott-Blair (Sean Connery) has retreated to a flat in Lisbon and thus misses meeting a woman named Katya (Michelle Pfeiffer) who goes looking for him at a trade fair in Moscow. She has brought a manuscript on behalf of a friend, hoping to have it published in the West. She uneasily leaves it with another English publisher who claims to know Barley, who promptly turns it over to British intelligence. The agency tracks Barley down in Lisbon and begins to grill him about the woman and the manuscript; he knows nothing about either, something they find hard to believe.

The manuscript is a detailed description of the shortcomings of the Soviet arms program, purporting to prove that the U.S.S.R. is really no threat to the West. The agency needs to know who wrote it and whether it is in fact accurate, and Barley finds himself reluctantly recruited as an amateur agent. He is sent to Moscow, where he contacts Katya. The author turns out to be a man nicknamed “Dante” (“Goethe” in the book), a scientist and engineer who works in military research. Barley had met him sometime earlier at a drunken retreat for writers outside Moscow and Dante was impressed with Barley’s passionate assertion that it was time to abandon outmoded, antagonistic states and work as individuals for a better new world. Dante believes that if it is revealed to the world that the arms race is essentially an economically crippling hoax, then the Cold War will inevitably end.

Once the identity of Dante is known, British intelligence connects with the CIA. If Dante is genuine, then the whole military-industrial complex is threatened, a whole economic system of governments and corporations will crumble. The Americans assert authority over the British and treat Barley as hostile and untrustworthy because he disdains Western corruption and has a strong emotional attachment to Russia. But Barley has no real interest in geopolitics – what’s more important to him is a growing emotional attachment to Katya and her children.

Sent back to Russia with a comprehensive set of questions for Dante to answer to prove that what he says is true, Barley has his own plans. Soviet intelligence is on to Dante and Katya – Dante is suddenly “hospitalized” – and Barley plays his own game, bargaining for Katya’s freedom by turning over the list of questions, which inevitably reveal details of the West’s own weapons programs. The espionage which was once central to Cold War spy narratives is sidelined and made irrelevant in the face of individual connections which traverse national differences.

As with Pinter’s script for The Quiller Memorandum, playwright Stoppard’s adaptation is more interested in the characters and how they navigate the complicated situation they find themselves trapped in than in the larger geopolitical machinations. The villains are the functionaries of agencies which now seem to exist only for themselves, to perpetuate their own power while the world rapidly moves on, leaving them behind. In this, The Russia House is almost utopian, an assertion of individual worth in the face of political negation.

A film of talk rather than action, The Russia House builds tension and suspense from Barley, Dante and Katya’s efforts to create their own meaning in a world which has for too long imposed unpleasant meanings on them. Connery, Pfeiffer and Klaus Maria Brandauer (as Dante) are all excellent as complex, nuanced characters, while the supporting cast is packed with great character actors: James Fox, Roy Scheider, John Mahoney, Michael Kitchen, David Threlfall, Ian MacNeice, Martin Clunes, J.T. Walsh … and, most surprisingly, director Ken Russell as a lively and eccentric British intelligence employee.

The image on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray is uneven, with noticeable dirt and occasional instability which is at times quite distracting. This is a pity given the significance of all that location shooting in post-Soviet Russia. The only extras are an isolated track of Jerry Goldsmith’s score and a brief making-of featurette (which on my copy has multiple sound drop-outs).

*

in Bernhard Wicki’s Morituri (1965)

Morituri (Bernhard Wicki, 1965)

Spies existed long before the Cold War, of course, but the structures of Cold War espionage were established during the Second World War. Perhaps in some ways, we can persuade ourselves that there was more moral clarity back when the conflict was overt rather than covert. We have an image of nobility and heroism when it comes to agents fighting against the obviously evil Axis powers. This was about war rather than politics and we could more easily believe in the righteousness of the cause. In reality, things were no doubt more complicated because, regardless of the global issues, it still came down to the messiness of individual actions in specific circumstances, matters of deception and betrayal.

Morituri (1965) was made the same year as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, but looks back to the war. Based on a novel by German writer Werner Jörg Lüddecke (who, among other things, had written the scripts for Fritz Lang’s Der Tiger von Eschnapur and Das indische Grabmal in 1959) and scripted by Daniel Taradash (whose varied filmography includes Fred Zinnemann’s From Here to Eternity [1953] and Sidney Pollack’s Castle Keep [1969]), the film combines tense action-adventure with increasingly complicated character motivations and moral choices. This isn’t too surprising given that the director was Bernhard Wicki, who six years earlier had made Die Brücke (The Bridge, 1959), a masterpiece about the corruption of a generation of children by Nazi ideology.

The adventure part of the film – an Allied agent boards a freighter heading from Japan to Occupied France, assigned to prevent the scuttling of the ship before it can be seized by an American blockade – seems familiar: men under stress in tight quarters triggering increasingly fierce interpersonal conflicts, dangerous encounters with enemy forces, deeply held convictions shaken by new knowledge. The story builds steadily towards a tense and violent climax, but along the way Taradash and Wicki take their time to create complex and interesting characters who have more depth than the stereotypes often found in such movies.

Marlon Brando, who seemed to have struggled to find a suitable form for his distinctive talent after his early success in the 1950s (what was with the excruciating embarrassment of The Teahouse of the August Moon [1956] or the stuffy mannerism of The Mutiny on the Bounty [1962]?), came to Morituri after starring in the worthy political thriller The Ugly American (1963) and the disposable comedy of Bedtime Story (1964), and he gives one of his really serious, committed performances as a cynical “pacifist” blackmailed by British intelligence to take on a dangerous mission in a war he doesn’t believe in (somewhat reminiscent of his “good German” in Edward Dmytryk’s The Young Lions [1958]).

Robert Crain has been hiding out in the Far East with all the material comforts he managed to sneak out of Germany. He has his art and his music and he disdains to take any interest in the global conflict. British officer Colonel Statter (Trevor Howard) comes to visit with an ultimatum: take on the job or be exposed to the Germans he’s hiding from. Crain reluctantly agrees, knowing that this may well be a suicide mission.

The ship “Ingo”, carrying 7,000 tons of rubber needed by the German military, has been assigned to the equally reluctant Captain Mueller (Yul Brynner), who despises the Nazis but has unshakable loyalty to Germany. His First Officer, Kruse (Martin Benrath), is a committed Party member who resents having been passed over for command in favour of an alcoholic who lost his previous ship while drunk. To complicate things, a number of criminals and political prisoners are assigned as crew, working their passage back to Germany where they will no doubt disappear into prisons or worse. Into this fraught situation comes Crain, using the identity of an SS officer. This character of necessity must perform at several different levels, presenting himself slightly differently to each person he meets in order to deflect suspicion and, eventually, gain allies from among the prisoners to carry out his mission.

Crain tries to placate the hostile captain, to enlist the vile Kruse by playing on his resentments, to convince a crucial political prisoner, Donkeyman (Hans Christian Blech), that they are really on the same side. And while juggling all these factors, he must search the ship and disarm all the scuttling charges – still motivated by a sense of self-preservation rather than any larger ideological concerns. This all changes when the “Ingo” rendezvous with a submarine carrying survivors from a torpedoed American ship, among whom is a young woman, Esther Levy (Janet Margolin), a surgical assistant who is also a German Jewish refugee. Her presence brings out Kruse’s extreme anti-Semitism, while also awakening something in Crain. In particular, her story of being brutalized and raped while the rest of her family were murdered makes him realize that there are stakes in the war which are more important than his own comfort and survival.

When Captain Mueller plunges back into alcoholism on learning that his beloved son has been awarded a medal for torpedoing a hospital ship, Kruse takes command and Crain tries to enlist the prisoners among the crew, as well as the newly arrived survivors from the submarine, to mutiny and deliver the “Ingo” to the Allies. Things get increasingly messy with a number of the prisoners unwilling to risk their lives – until Esther submits to being raped by them, as she once was by the Germans. Horrified by the behaviour of both sides, with the mutiny failing as Kruse ruthlessly starts executing those who oppose his authority, Crain reconnects the scuttling charges and triggers explosions throughout the ship. As the remaining crew escape in the lifeboats, Crain and Mueller remain aboard, now in an uneasy alliance, waiting for American ships to reach them before the “Ingo” and its valuable cargo sink …

Morituri is tense and gritty, moving at a deliberate pace as the tension gradually increases. Wicki draws excellent performances from the entire cast, with Brando and Brynner never better, and Margolin and Blech standouts among the supporting players. Benrath’s Kruse provides a thoroughly hissable villain among the more sympathetic yet flawed crew.

Although the print source is a bit worn, with occasional scratches and softness (some of the day-for-night and fake fog scenes are quite weak), Conrad Hall’s black-and-white photography is excellent, packed with gritty detail below decks. It would have been nice to have a commentary, but the Twilight Time Blu-ray offers only an isolated track for Jerry Goldsmith’s score.

Comments