Abbas Kiarostami’s The Koker Trilogy (1987-94):

Criterion Blu-ray review

In a sense, I came to the work of Abbas Kiarostami backwards. The first of his films that I saw was Through the Olive Trees (1994), at a screening during its successful arthouse release in the mid-1990s. I was mesmerized by its atmosphere, the glimpse it gave into an unfamiliar place and the lives of its inhabitants. But in retrospect it’s obvious that I really didn’t understand it at all, because it was the culmination of a remarkable, intricate, multi-layered three-part work retrospectively dubbed The Koker Trilogy, which stands as one of the great achievements of world cinema. To fully understand that greatness, it’s necessary to see the three parts in order, something I’ve only now managed to do thanks to Criterion’s superb three-disk Blu-ray set. (I’d only previously seen the first and second parts on rented VHS tapes several years after that screening of part three.)

Kiarostami himself didn’t refer to the three films as a trilogy, although he accepted that designation from others. It all depends on how one defines “trilogy”: if it’s a three-part narrative which progresses through episodes in a more or less linear fashion (the Godfather films, Star Wars, etc), then Kiarostami’s films are something else. Rather than linear progression, they might be said to accumulate vertical layers, beginning with a foundation firmly rooted in a familiar kind of realism, then progressively interrogating how that realism is constructed, and finally interrogating the nature of cinema itself, the intricate relationship between reality and illusion, lived experience and the creative interpretation of that experience … between truth and lies and, as Kiarostami put it, arriving at the truth through lies.

Kiarostami, who had set up the film department at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, had been making shorts, documentaries and features for almost two decades when he wrote a script called Where is the Friend’s House?, which he intended for someone else to direct. Like much of his work to that time, its focus was on childhood and education. He was reluctantly persuaded to direct the project himself and set about finding an appropriate location for the story of a young boy’s life in a small village, eventually settling on Koker, a couple of hundred kilometres from Tehran. He liked the landscape and regional accent, casting non-professionals from the neighbourhood.

Where is the Friend’s House? (1987) is one of the greatest films about childhood ever made, seemingly so simple on its surface, yet accumulating the power of an epic quest through which its eight-year-old protagonist learns how to navigate an unsympathetic world and discover his own strength and resourcefulness through a deeply felt responsibility for others’ well-being.

In a small rural classroom, Ahmad (Babak Ahmadpour) watches his friend Mohammad Reza (Babak’s brother Ahmad Ahmadpour) berated and humiliated by their teacher for turning his homework in on a piece of paper rather than in his notebook. The teacher tears up the paper and says that if it happens again the boy will be expelled.

This opening scene sets up a world fraught with danger, ruled by harsh and seemingly unreasonable adults (the teacher does have a rational excuse for his demands, but his method of applying the rules is brutal). With this experience fresh in mind, Ahmad discovers when he gets home and starts to do his homework that he has accidentally taken Mohammad Reza’s notebook. This means automatic expulsion for his friend. Obviously he must somehow get the notebook back to him, but when he tries to explain this to his harried mother (Iran Outari), she simply doesn’t hear what he’s telling her, assuming he just wants to skip homework and go play with his friend. She’s busy with doing laundry in the courtyard and dealing with a crying baby, what attention she gives Ahmad limited to irritation and a demand that he get on with his homework – although she constantly interrupts him to insist he do one chore or another.

Ahmad is very small and the world he exists in barely sees him as a person in his own right, yet he has an awareness and concerns which, for him, are very important. Kiarostami’s genius lies in the almost mystical way he aligns the audience with Ahmad’s consciousness. He draws a remarkable performance from Babak; we can see the actual process of thought in the boy’s large dark eyes, his initial attempts to convey urgency to the adults around him, his realization that his problem has absolutely no significance to them, and finally his understanding that he must act, even in defiance of those adults who have absolute power over him.

This is the beginning of Ahmad’s quest, a journey packed with suspense, obstacles to be overcome, all intensified by a desperate feeling that time is running out. Told to go and fetch bread, Ahmad grabs Mohammad Reza’s notebook and escapes the courtyard. He knows that his friend lives in the next village, Poshteh, and for the first time we see what becomes a defining image in the trilogy: the hill separating the villages with a sharply defined zigzag path cut into the dry ground and a single tree on the crest. This hill and its distinctively geometric path binds the three films together and comes to represent the sharp, seemingly arbitrary changes the characters’ lives will go through.

On the far side, Ahmad descends towards what is clearly a much larger village than his own, but he has no address for his friend. He quickly discovers that Poshteh is like a labyrinth with many parts and that his friend’s surname is very common. He repeatedly asks directions, sometimes getting no help, sometimes being sent the wrong way … and night begins to fall.

Ahmad’s journey has digressions and dead ends, but each encounter teaches him something about the world … particularly about the limitations of adults and the need to find his own solutions. His way of finally fixing the problem caused by inadvertently taking Mohammad Reza’s notebook is generous and delivered quietly, without expectation of reward or recognition of the enormous effort it took to achieve. The final scene of the film has the air of an epiphany, a revelation of the resilience and potential contained in this small child.

Where is the Friend’s House? is a masterpiece of neorealism which evolves into an almost mystical evocation of the poetry of ordinary life. And there it might have ended, if not for a catastrophic event which struck Iran a couple of years later. When a devastating earthquake occurred in the region around Koker, killing 50,000 people, Kiarostami set off to find out whether the children in his cast had survived. That search became the basis of a new film, And Life Goes On (1992). Unlike Where is the Friend’s House?, this one had no script, just a brief outline based on Kiarostami’s experiences, with scenes being written as they were filmed. The earlier neorealism is here replaced by a documentary approach, although this is complicated by a fictional overlay.

Instead of giving a straightforward factual account of his own experiences in the devastated region, Kiarostami cast a non-professional, Farhad Kheradmand (an economist he met at a party), as the Director of a film called Where is the Friend’s House? who drives with his son Pouya (Pouya Payvar) into the earthquake zone to find out the fate of the two boys from the film. All this we only gradually learn on the road as father and son talk about various things (the landscape, grasshoppers) while we see increasing signs of the damage – collapsed buildings, people digging through rubble, wrecked cars. The journey becomes more difficult, with damaged roads and long traffic jams, and the Director turns off on a side road, hoping to find a back way into Koker.

The Director’s search parallels Ahmad’s quest in the first film; in a series of encounters, he asks for directions from people who are sometimes helpful, sometimes not, all of whom have been touched by the disaster. Amid a landscape in ruins, these people are dealing with terrible loss, overwhelming grief, but also stoically getting on with their lives. Kiarostami immerses us in this trauma … and we forget that this was all filmed months later, that these people (all local non-professionals) are re-enacting their experiences with a fictionalized version of Kiarostami.

The people we see in And Life Goes On have lived through the events depicted, but are already in reality rebuilding. Grief is leavened with a determination to move forward, giving the film an unexpectedly hopeful tone. Although traumatized, these people are working together to rebuild their lives as a community. Late in the film, the Director sees the inhabitants of a cluster of tents on a hillside setting up a television antenna so that the community can watch a World Cup football match. When he asks a man how they can be interested in a game at a time like this, the man replies that the World Cup only happens once every four years and life goes on.

And Life Goes On begins in the middle of something which we only gradually understand and it ends in the middle of something whose resolution we remain uncertain of. The remarkable final shot runs several minutes, looking down at a narrow dirt road which runs down one hill and up another. We watch the Director’s car coming down from the right, passing a man carrying a heavy can, making the switchback turn at the bottom, then starting up to the left. The car makes it almost to the top of the hill, slows, then starts rolling back. It stops, tries again, fails, then rolls all the way back to the bottom, where it apparently stalls. The man carrying the can has caught up and gives the car a push to get it going again. He gets in and the Director starts up the hill again, this time making it over the crest and continuing on the way towards Koker with his helpful passenger.

The film ends with its central question unanswered. We still don’t know the fate of Babak and Ahmad, but we have seen a community rebuilding itself after the disaster through cooperation and a stoic acceptance of what fate (and God) have sent their way.

In Where is the Friend’s House?, Kiarostami uses neorealist techniques to create a psychologically and socially authentic narrative. Those techniques were developed by filmmakers who wanted to break free of the artifice of classical narrative cinema – but neorealism itself is not free of artifice. It still adheres to certain narrative imperatives, but by using a documentary-like style, appears to give more direct access to reality.

In And Life Goes On, Kiarostami continues to use those documentary techniques, but adds a layer of self-awareness which questions that access to reality – firstly foregrounding the artifice of filmmaking itself by casting someone else as the Director of Where is the Friend’s House?, but also by failing to provide the audience with the kind of narrative information we expect. This film emphasizes the limits of what documentary can tell us when the filmmaker resists imposing the satisfactions of a well-formed story on the random, contingent experiences he is attempting to observe. This is something like adding the critical self-consciousness of the nouvelle vague to a neorealism base … which itself creates new forms of artifice (the impression of randomness in the second film is itself artfully constructed).

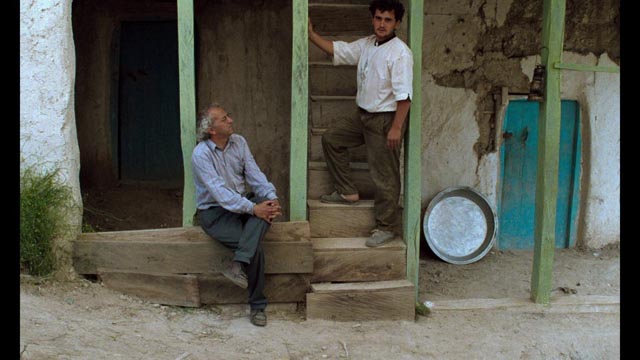

When And Life Goes On was released, Kiarostami related a story from the production about the filming of one particular scene. Pausing among the ruins of Poshteh, the Director meets a young man named Hossein (Hossein Rezai) arguing with his wife about where his white socks are. The Director discovers that the couple just got married, in fact on the day after the earthquake. Since they had both lost dozens of relatives, if they had observed propriety the lengthy process of mourning would have postponed their wedding indefinitely; so they broke with tradition in order to get on with their lives.

The story Kiarostami told was that the woman playing the new wife hated the man cast as the young husband and the shooting was complicated by this conflict. It was suggested to him that this in itself would make an interesting film and he soon began work on Through the Olive Trees (1994), returning to the Koker area to add new layers of complication to his interrogation of the relationship between cinema and reality.

The new film begins with prominent Iranian actor Mohammad Ali Keshavarz facing the camera and telling us that he has been cast in the role of the Director of And Life Goes On. Behind him is a field full of young women dressed in chadors and a woman named Mrs Shiva (Zahrifeh Shiva) tells him they’re running out of time. With her following to take notes, he walks through the crowd, chatting with the girls. One asks what’s the point of filming? Will they ever get to see it?

And so from the first moment we’ve already gone beyond the self-awareness of And Life Goes On. We are in a film about the making of the previous film which is telling us that this film itself is being made by someone else who is recreating earlier experiences. Within the film the on-screen Director has told us that he is an active participant in this construction of a reflected/remembered reality. The illusion of reality we saw in Where is the Friend’s House? has been turned on its head; we are being shown the construction of the illusion … Kiarostami is actively deconstructing cinema to comment on his previous construction, a magician following a successful trick with an explanation of how the trick was performed.

But following this opening scene, we immediately find ourselves back in the kind of documentary fiction we saw in And Life Goes On, observing a film crew making preparations to shoot in the abandoned ruins of Poshteh. During these initial moments, in a brief, seemingly off-hand, almost throwaway scene, we receive an answer to the question which hung unanswered over And Life Goes On about the fate of Babak and Ahmad; while Kiarostami places no apparent emphasis on the moment, anyone familiar with the previous two films experiences it with deep emotion.

With cast and crew assembled at last we watch the Director’s struggle to shoot that single scene from And Life Goes On, while being given access by the unseen meta-director (Kiarostami) to the larger context surrounding that task – namely the conflicted relationship between Hossein and the young woman cast as his wife Tahereh (Tahereh Ladanian, who was given the role when the original actress from the previous film not surprisingly refused to work again with Hossein, whom she disliked). So no matter how many layers Kiarostami creates to expose the artifice of filmmaking, he simply can’t avoid his own role as the primary creator, the shaper of the “reality” we see on screen.

While the Director does take after take of the scene (which involves Farhad Kheradmand once again appearing as the Director we saw in the previous film), between takes Hossein tries to get a response from Tahereh, who completely ignores him. He had seen and fallen in love with her before the earthquake, but her mother rejected him as a potential husband because he was an illiterate labourer. While both her parents died during the earthquake, her grandmother also refuses him … but he’s convinced that she feels something for him because of a look she gave him in the cemetery one day. He argues at length about the need to overcome the disaster by moving ahead with their lives, and that this would be better done together.

In one of the film’s most powerful and moving scenes, the Director draws this story out of Hossein, who passionately argues that life’s problems could all be alleviated if all class boundaries were stripped away – that if the rich would marry the poor, the literate the illiterate and so on, everyone would be raised up together. This is the most explicit expression of a subtext running through the films, that the revolution (for which the disruption of the earthquake stands as a metaphor) has failed to fundamentally change a rigidly stratified society and improve the lives of ordinary people.

While the Director eventually has to make do with what he can get from the dramatized scene after numerous takes in which he never quite gets the dialogue he wants, Kiarostami seems to allow the actual story of Hossein and Tahereh to escape his control. When filming is over and the crew begin arguing among themselves, Tahereh sets off on foot and the Director urges Hossein to seize this opportunity and follow her, which he does, continuing to argue his case and plead with her for a clear sign whether she has feelings for him or not.

This continues through an olive grove, where they pass Kiarostami and his crew filming a scene from And Life Goes On – adding another layer by finally inserting himself into the narrative space already occupied by his two surrogate directors – and then on up the iconic hill with its zigzag path which visually sutures the three films together. (I was surprised to learn from the disk extras that this path was actually created by Kiarostami for Where is the Friend’s House?; and here it still is, part of the landscape years later, a mark left on reality by the fiction of the original film.)

Here, in an echo of the previous film’s ending, we get a static wide shot from the hilltop, looking down over an olive grove through which Hossein continues to pursue Tahereh. But this time we are supplied with a specific point of view, that of the Director (Keshavarz) who has climbed the hill and watches from the shade of the single tree at the crest. Tahereh makes her way across the open ground beyond the grove, until she’s a tiny figure in the distance with whom Hossein finally catches up. She seems to stop, perhaps speaks, and after a moment Hossein turns back and begins to run.

We (and the Director) have no way of knowing what has passed between them, whether she has finally acquiesced and he’s running in joy, or whether she has definitively rejected him and he’s running in despair. We are left with the feeling that the Director (and Kiarostami) have set something in motion over which they ultimately have no control … in fact, of which they themselves can have no final knowledge. This of course is a reflection of their (and our) relationship with reality – but as the filmmaker, no matter how visible he makes the process of creation and cues us to the levels of artifice from which art grows, even here we are left with an undeniable awareness that Kiarostami has artfully constructed an illusion of the limitations of art.

The three films of The Koker Trilogy interrogate the nature of cinema and its relationship to reality and ultimately confirm Kiarostami’s assertion that the essence of art is lying as a way to find truth.

*

The Disks

All three films were scanned from the original camera negatives, Where is the Friend’s House? and And Life Goes On in 2K, Through the Olive Trees in 4K. There is some visible print damage in Where is the Friend’s House?, but all three films show a great deal of detail and have a film-like texture. Colours tend to be a bit muted, but this seems appropriate to the dry, sun-baked landscape. Audio is very clean in all three films.

The Supplements

Each disk has interesting and informative supplements covering the creation of the films (and debating whether they do actually constitute a trilogy – which seems to be a rather academic issue to me, given the numerous connections among the films) and Kiarostami’s career and influential position in Iranian cinema. These include interviews with film scholar Hamid Naficy (15:11) and Kiarostami’s son Ahmad (14:12), a discussion of the films between scholar Jamsheed Akrami and critic Godfrey Cheshire, and a Q&A from 2015 with Kiarostami interviewed on-stage in Toronto by programmer Peter Scarlet about his life and work – this is a bit of a slog because it required simultaneous translation which slows the conversation down considerably.

Abbas Kiarostami: Truths and Dreams is a 1994 French documentary by Jean-Pierre Limosin from the series Cinemas de notre temps in which Kiarostami retraces his journey to the earthquake zone and talks to some of the people he cast in the films (including Hossein, now married with a young child), as well as the star of his earlier film The Traveler (1974).

The And Life Goes On disk includes a commentary by Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum which focuses on the importance of this particular film in the development of Kiarostami’s approach to filmmaking.

The first disk includes Kiarostami’s 1989 documentary Homework, a fitting companion for Where is the Friend’s House? in which he interviews students and a couple of parents about issues surrounding the education of children in contemporary Iran. This is a surprisingly dark film, starting with an indoctrination session before the school day begins, with the kids en masse chanting revolutionary slogans and calling for death to Saddam. In the individual interviews, we hear again and again how the kids are subjected to rote learning, often receive little help or support at home (many have illiterate parents), and don’t even know what Kiarostami means when he asks if they ever receive encouragement. Most, however, are regularly hit or beaten by their parents. Homework retroactively provides a chilling context for Ahmad’s determination to do what he knows is right against the opposition and indifference of adults in Where is the Friend’s House?

The booklet essay is by Godfrey Cheshire.

In a year which has already produced quite a few significant releases, The Koker Trilogy may be Criterion’s finest. It would be hard for them to top this superb edition of Kiarostami’s masterwork.

Comments