Intimidated by Art

As someone who has dabbled in various creative activities throughout my life, I find genuinely creative people somewhat intimidating. Although I first began to write (and draw) stories when I was five or six, wrote my first (unpublished) novel at seventeen – followed by eight or nine more (all unpublished), along with numerous short stories and unfilmed movie scripts – I’ve never had the drive to fully commit. I enjoy the process of inventing stories, but not all the hard work which necessarily follows in order to form a finished work out of that initial foundation. Back in the 1990s, I did make a handful of short films and became an editor on other people’s projects – which turned out to suit my temperament much better; I had a knack for drawing the value out of other people’s efforts and had a pretty good career for about fifteen years, working on shorts, a couple of dramatic features, a documentary television series and a number of worthwhile documentary features. In other words, when it comes to creative work, I seem to be a better follower than leader.

I admire the drive and commitment of genuine artists although they remain mysterious to me. For me, reading, or watching documentaries, about artists is like studying an alien culture whose language and forms of expression are only partially understood. I love the work of filmmakers like Orson Welles or Andrei Tarkovsky, but I don’t think I’d have wanted to meet either of them because their intellectual and aesthetic frames of reference would have been beyond my grasp. I will happily immerse myself in their work even though I’ll never really understand how they arrived at it.

These thoughts arise from my recent viewing of two modest documentaries which offer glimpses of this higher level of creativity. The very modesty of the films – Kaku Arakawa’s Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki (2016) and Chris Rodley’s In My Mind (2017) – reflects the limits to understanding the mysterious processes which result in great works of art.

*

Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki

(Kaku Arakawa, 2016)

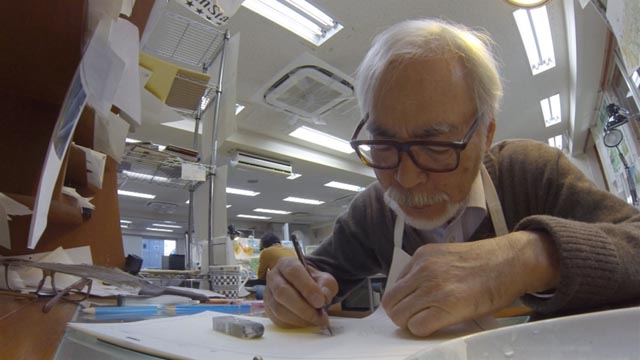

Never-Ending Man, made for the Japanese network NHK in 2016, is a modest and intimate portrait of the man who may well be the greatest filmmaker in the history of animation. It begins with a 2013 press conference at which Miyazaki announces his retirement – again. He had done it a couple of times before, only to return a year or two later to work on another feature. Directed and photographed (on unobtrusive portable equipment) by Arakawa, the doc quietly observes Miyazaki’s daily routines at his atelier connected with the now-shuttered Studio Ghibli. Miyazaki makes tea, eats ramen, and sits at a table where he compulsively sketches on loose sheets of paper.

He speaks of growing old, of no longer having the focus and stamina to make movies, and of the deaths of people who worked with him over decades on his features. The tone is both resigned and melancholy; he finds purpose and self-worth in things yet to be done, rather than things already accomplished, and the idea that there will be no more projects distresses him. And slowly, as the seasons change, he begins formulating an idea for a short film called Boro the Caterpillar … but the difference is that he’s considering CGI rather than hand-drawn animation.

Known for giving opportunities to young artists just beginning their careers, he starts to work with a team of computer animators, who seem to think that they will be able to realize his ideas quite quickly. As they begin to develop the computer models for the caterpillar character, Miyazaki is at first patient, but then he gradually becomes frustrated – there is a difference between the technical side of CG and the expressive needs of character and emotion. In order to help the young team, he draws more and more elaborate storyboards and eventually generates rough sketch cels for entire sequences which put increasing pressure on the crew.

What had seemed like a small, quick project stretches on for months and Miyazaki becomes disillusioned while trying not to crush the crew’s enthusiasm. If only they can complete the opening sequence to provide a firm basis for the rest of the fifteen-minute film … and then Miyazaki has a sudden realization of what’s missing, why it’s not working, an instinctive inspiration which gives the crew the renewed energy they need … and progress quickens.

But the process of working on this small, contained project has re-energized Miyazaki. Despite his age, his tendency to tire more quickly, and the daunting prospect of years of intense work, he proposes to his friend and producer Toshio Suzuki that they embark on a new feature. He’s not sure yet what it would be, but he needs to immerse himself once more in his work … and so for perhaps the third time, Miyazaki comes out of retirement …

Never-Ending Man is open-ended because Miyazaki’s life and work continue. He’s in pre-production now on his twelfth feature, the story of a teenage boy’s coming-of-age.

What emerges from the film is a portrait of a quiet, humble man who is absolutely dedicated to his art and relentless in pursuit of his own ideas of perfection. This leads him to push hard on the limitations of those who work with him, at times making him seem almost cruel in his judgments. (I’m reminded of his reaction to the first screening of his son Goro’s feature From Up on Poppy Hill [2011], a quite lovely film which Miyazaki criticizes sharply for many small creative failures.) There’s one particular sequence in the doc which reveals with absolute clarity the moral conviction which underlies every aspect of his creativity: a company experimenting with AI in the creation of CG animation screens a demo reel for Miyazaki and his crew, a shot of a painfully contorted body crawling endlessly across a floor – something out of a nightmare or horror film – and Miyazaki responds with quiet intensity that this appalls him, that there is no human empathy displayed in the technically polished sample, that in fact it is an affront to all that’s human. It’s as close as he comes to showing anything like anger, but he remains calm and direct, unshakably certain in his own view of the world. (It reminded me of Andrei Tarkovsky’s moral certainty, frequently expressed in his diaries, the idea that any compromise would corrupt the art he was trying to create.)

There’s a home movie feel to Never-Ending Man – Arakawa has a fine eye for composition, and the leisurely editing rhythms match the calm energy of his subject, but the sound is unpolished and seems to have been captured mostly on the camera’s built-in mic – but its unobtrusive simplicity allows Miyazaki’s personality to shine through. My only caveat about the disk itself (from Shout! Factory and GKids) is that it doesn’t include Boro the Caterpillar as an extra. There is an alternate shorter edit of the doc, however, with English narration.

*

In My Mind (Chris Rodley, 2017)

Patrick McGoohan may not have had an impact on cinema and popular culture comparable to Miyazaki – he was an actor who occasionally wrote and directed – but one creation in particular stands as a landmark which has inspired passionate supporters and equally frustrated detractors over five decades.

Having had a strict religious upbringing, McGoohan brought a seriousness and intensity to his work as an actor in theatre, in film and on television, which made him much admired by his contemporaries. He moved between high art and popular culture with apparent ease – the former aspect of his work can be seen in Arthur Dreifuss’ film of Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow (1962) and, most particularly, in the terrifying intensity of his performance in Michael Elliott’s BBC production of Ibsen’s Brand (1959).

The pop culture aspect is on display in a wide range of projects like Cy Endfield’s Hell Drivers (1957), Disney’s TV adaptation of Russell Thorndyke’s Dr. Syn: The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh (1964) and David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981), but most particularly in the internationally successful series Danger Man (aka Secret Agent, 1960-67). Preceding the big screen debut of James Bond by several years, McGoohan’s John Drake was a no-nonsense globe-trotting agent assigned to defeat any elements which threatened world peace. From the beginning, McGoohan insisted that Drake would stick to the job and not engage in any extraneously salacious shenanigans – he felt there was no place on television, with its family audience, for sex. (This was a less puritanical attitude than it might at first seem as he was less restrictive about his work on the big screen.)

After years of playing Drake, the actor became restless and eventually demanded to be released from the series despite its continuing success. Incorporated Television Company (ITC) mogul Lew Grade not only agreed to let McGoohan go; he also agreed to back the actor on a then-vague idea about a new series. This would be far more experimental, although in some ways it could be seen as an offshoot of Danger Man. It involved a top agent resigning from his agency only to find himself kidnapped and relocated to a strange, isolated community where unidentified forces try to break him and get him to reveal what he knows and why he resigned – these forces may be his own former bosses, or they may be from an enemy agency. That’s never resolved and, as the seventeen episodes unfold in an elaborate, circular game of cat-and-mouse, it gradually becomes irrelevant as the questions being asked grow less specific and more existential.

The Prisoner (1967-68) is an allegory disguised as an action-adventure series about spies and bureaucrats. Its central conflict is the struggle of an individual to maintain his autonomy and identity against larger social and political forces which are determined to contain and constrain him. Its endlessly repeated refrain is “I am not a number; I am a free man”, but as it unfolds it interrogates the very idea of what being a “free man” is in a social context. The series is obviously weighted in favour of the unnamed individual (designated Number Six) against the petty bureaucrats who are interchangeable, and it could be argued that there are times when Number Six’s absolute certainty becomes almost (if not entirely) insufferable, sustained only by the caricaturing of the idea of society represented in the Village.

But while the deeper meanings of the series remain elusive and debatable, it is an exhilarating piece of entertainment which gleefully sticks its thumb in the eye of commercial television expectations, becoming outrageously challenging in its final two episodes which erupt into full-blown theatre of the absurd abstraction, confronting an audience looking for resolution with the very idea that nothing can in fact be resolved. Life itself, it says, is a big unanswerable question – but the search for answers can be exciting, scary, funny and satisfying. The show is packed with wit and style and populated by a collection of great actors who all engage fully with the spirit of the enterprise.

The Prisoner was also a very personal project for McGoohan, who had been mulling over the concept for years before he got the go-ahead from Lew Grade, and who was deeply involved with every aspect of the show’s development and execution – working closely with producer David Tomblin and story editor George Markstein on the pilot episode which sets up the distinctive world, writing a total of six episodes himself and directing five as well as starring in all but one (in Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling Number Six has his personality swapped into another man’s body). On a more prosaic level, the allegory can be seen as McGoohan’s own rebellion against being trapped in the Danger Man series for years and bristling against the idea that he should have stayed with it because it was still successful.

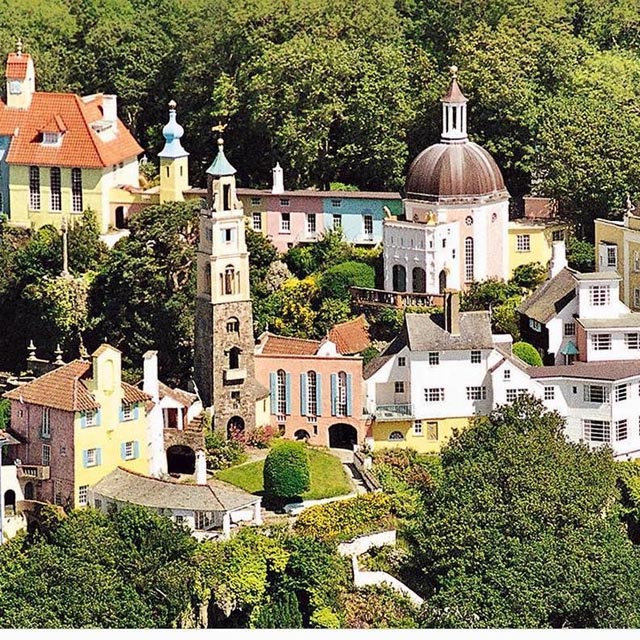

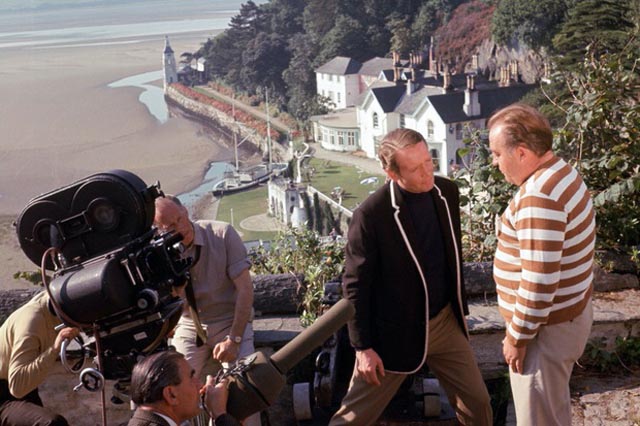

One other key factor makes The Prisoner the fascinating work that it is – in fact, it may never have existed if not for McGoohan’s discovery, during the shooting of an early episode of Danger Man, of the artificial village of Portmeirion in Wales, a synthetic, quaint, colourful and eccentric invention of the architect Clough Williams-Ellis. The physical existence of this place along with its deep air of unreality triggered a spark in McGoohan; the place itself inspired the series’ conceptual world and engaged audience interest – the series became a danger-filled theme park attraction, something rich and magical given added depth by the fact that it was filmed not on a set but in a real yet fantastic location.

Originally planned as just seven episodes, but expanded to seventeen at ITC’s insistence, the increasing abstraction of The Prisoner grew in part from McGoohan’s resistance to that expansion – asked to cater to popular success, he responded by being deliberately difficult and obscure. As viewers and critics demanded clarity and explanations, he retreated from knowability. Asked what it all meant, he clammed up and moved on.

Which is why it was surprising that he agreed to sit down for an interview in 1983 with an inexperienced filmmaker named Chris Rodley. Rodley was making a documentary about the series (eventually completed as Six into One: The Prisoner File) and went to Los Angeles to meet the show’s creator and star. Things didn’t go well. McGoohan disowned the resulting doc, and made one of his own. (Reputedly, Six into One was a bit of a disaster and has never been seen since its one original screening on Channel 4.) Much of the material from what became two lengthy sessions remained unused until Network commissioned a new program to go along with their 50th anniversary Blu-ray release of The Prisoner in 2017.

The resulting doc, In My Mind (2017), is not an account of the show’s origins and production; it is not a startling revelation of the elusive deeper meanings from the mouth of its creator. It is rather a look at the difficulty of getting answers from that creator, of turning the creative impulse and process into easily digested words. Framed by Rodley’s account of his 1983 expedition and annotated with clips from a new interview with McGoohan’s daughter Catherine, it is the story of a failure which, many years later, turns out to be illuminating in itself.

In the initial interview session, which took place in an empty house somewhere in Los Angeles, McGoohan is bristling with irritability. He is uncomfortable on camera and prickly with Rodley and his crew. He quickly takes charge and begins directing the session, proposing camera positions, editing points, taking over the space and moving through it as if trying to evade the camera. He tries to control and frame what he says, assuming for himself the role which ought to be Rodley’s. Yet what he says is little more than the familiar details of how the show came to be, with little about its nature as a work of dramatic art or those elusive meanings.

He directs his own exit (exiting the house with the show’s catchphrase “Be seeing you”), leaving Rodley and his crew in defeat. But later, when Rodley and the crew have taken a trip up the coast and stopped at a hotel overlooking the sea, it turns out that for some reason McGoohan has followed them and he sits down for a second interview. This time, though, he seems more relaxed and open. Having established dominance in the first session, he is now generous. He doesn’t actually say anything new and revelatory, but now he is less defensive and hostile. Together, the two sessions reveal McGoohan’s own ambivalence about the legacy which has overshadowed much of his life, both creatively and personally. The Prisoner had emerged in reaction to his feeling trapped by John Drake and Danger Man, only to create a bigger and more lasting trap which he had ironically built himself.

What is revealed by In My Mind is not the secrets of The Prisoner, but rather the inevitable paradox of the actor’s craft: the burning commitment to express something by becoming someone else, only to find himself overtaken and overshadowed by that other persona. The act of creating is also an act of self-erasure, the more successfully achieved the more obliterating. In the first session, McGoohan exudes resentment that these people have come to talk to him not about himself but rather about the thing which has made it so difficult for him to exist as himself. But in the second session, he has let go of this conflicted egotism and is resigned to the fact that what he has created exists in the world as a separate thing which is larger than himself and will continue to exist beyond his own life and identity.

The image on Network’s Blu-ray is inevitably uneven given the flaws in the original material from 1983, but the content is fascinating so technical quality isn’t really an issue. The disk includes as extras a lengthy section from the second interview session (30:59) and additional clips from Catherine McGoohan’s interview (25:53).

Comments

Any convenient (for me) way to see In My Mind? Also, Where Is the Friend’s House?, The Wild Boys, and/or The Krays?

The library system has none.

Hi Grant … I can lend you copies of In My Mind, Wild Boys and Where is the Friend’s House? … afraid I don’t have a copy of The Krays, though (one of many oversights in my otherwise bloated collection!)…