Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983): Criterion Blu-ray review

Following the surprise international success of his second feature, Gregory’s Girl (1980), Scottish writer-director Bill Forsyth teamed up with one of the most powerful producers in England, David Puttnam. It seemed like an odd pairing, with Puttnam just coming off his Oscar win for Chariots of Fire (1981) – one of those prestige period films with which the British film industry (and the Academy) were so enamoured in the 1980s (earnest and impeccable, is anyone still watching it?). It would be hard to get further from that than Forsyth’s scrappy, no-budget teen comedy-romance. But in the event, it turned out to be a fortuitous partnership.

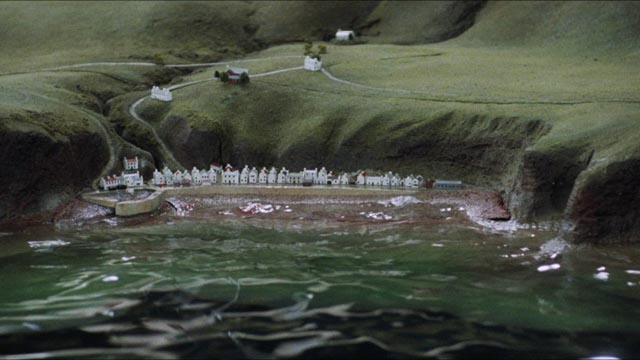

Puttnam suggested that Forsyth make something about the impact of the North Sea oil boom on Scotland, but what eventually emerged, while it did touch on that social and economic upheaval, was deceptively light and indirect. Local Hero (1983) owes something to the tradition of comedy indelibly forged by Ealing Studios in the 1950s – its depiction of a remote Scottish community suddenly faced with unexpected good fortune is reminiscent of Alexander Mackendrick’s Whisky Galore (1949) – but Forsyth adds notes of magical realism which expand the story far beyond its surface charms.

A popular success on its release, Local Hero was nonetheless largely seen as a whimsical trifle. Looking back on it now, it appears remarkably prescient, its themes deeper and more urgent. What had appeared to be a light-hearted comedy of culture clashes in fact engages with the urgent necessity of dealing with fossil fuel dependence and climate change … its whimsy rests on much darker things.

The surface level is a very funny narrative involving an ambitious junior executive with a Texas oil company, Mac (Peter Riegert), whose bosses, mistakenly thinking he’s Scottish, send him to Scotland to make a deal. (His Hungarian grandfather changed his name to McIntyre because he thought it sounded more American.) The plan is to buy an entire fishing village and its bay in order to build a terminal for the transportation of North Sea oil. Mac, of course, is tasked with getting the site as cheaply as possible.

It’s hard to keep such plans secret, so even before he arrives the villagers know why he’s coming. Local innkeeper and accountant Urquhart (Denis Lawson) has been elected to negotiate for the villagers, while the population put on a display of their undying devotion to an old way of life even as they excitedly plan what they’ll do with all the money they expect to receive.

Mac, trying to remain unobtrusive, takes his time and as the days go by he slips into the rhythm of a life dictated by isolation and the sea. His hectic materialistic existence back in Houston becomes more distant and he grows to understand what it is that he’s asking these people to sell … in a way, their deception is too good and he sympathizes with their feigned reluctance.

There are two other threads which complicate his assignment. These are the film’s magical elements, adding a utopian counterpoint to the blatant materialism of the main story. First, there’s Mac’s eccentric boss Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster), who inherited the oil company from his father and has little attachment to his wealth – in an early scene as the board discusses plans for the terminal, they have to whisper because a disinterested Happer is quietly snoring at the board table. He devotes himself instead to an interest in astronomy, by definition something larger and more abstract than the pursuit of yet more money.

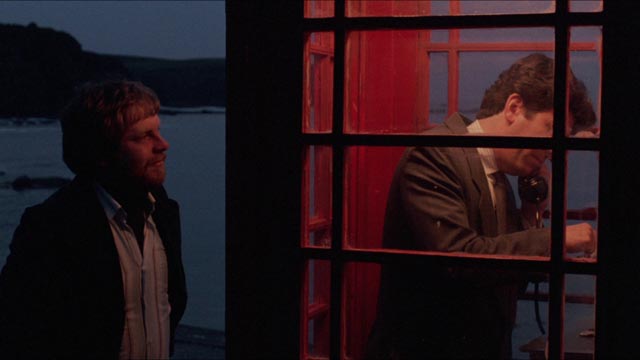

When Mac meets the boss for the first time to receive his assignment, Happer doesn’t talk about the land deal; instead he wants Mac to keep an eye on the sky and report back on any unusual phenomena he might see. While this directive confuses Mac, it also plants a seed, priming him to pay particular attention to the natural world he’s being dropped into.

Second, while the entire village is determined to sell up and use the money to make new lives for themselves, there are two people for whom the money and the oil company’s plans mean nothing. One is Marina (Jenny Seagrove), a young biologist who works for the oil company, surveying marine life in the bay without knowing the larger plan – she believes Mac has come to deal with her own proposal for a scientific research station at the site. Mac’s local assistant Oldsen (Peter Capaldi) is immediately caught under Marina’s spell, tormented by his knowledge that her plans are not only going to be unfulfilled, but actually destroyed by the development of the terminal. His feelings are only intensified when he begins to suspect that her connection with the bay is more than a scientific passion – she may be an honest-to-god mermaid.

The other potential roadblock is Ben (Fulton Mackay), an old man who lives in a shack on the beach, who turns out to be the legal owner of the whole shoreline, granted by royal decree generations earlier. Ben survives by beachcombing and lives in quiet harmony with the bay’s rhythms; he has no need of money and no intention of selling out.

Marina and Ben represent an existence which is in balance with Nature, while Mac (at least initially) and the villagers see the land as something to be exploited for financial profit. It’s through Marina and Ben that a nascent environmentalism runs through the film and it’s through the equally fantastic figure of Happer that the advantage swings in their favour. Arriving because of Mac’s reports on activity in the sky (meteor showers, the Aurora Borealis), Happer is just in time to interrupt what could have become an unpleasantly violent encounter between the angry villagers and Ben. And after a night of conversation with the old man (unheard by us and the villagers), Happer emerges with less interest in big business deals and a greater appreciation of the magical land and seascape. Caught in an expansive mood, he is receptive to Oldsen’s suggestion that the bay would be ideal for a marine laboratory as well as an observatory – “the Happer Institute”.

In other words, an entirely different and sustainable form of development, one which would bring some kind of profit to the villagers but without destroying the natural environment.

Apparently Puttnam was turned down for funding by numerous studios and distributors who felt that Forsyth’s script lacked conflict and that nothing much happened. In a sense, they were right … Local Hero is on its surface a small, whimsical comedy about a man driven by purely material concerns who, through his encounter with these Scottish villagers, realizes that his busy life is essentially empty of real meaning. When Mac returns to Houston, he no longer feels any connection with his fast car and his highrise apartment. The film’s final image, a wide shot of the village with its single phone box at dusk as the phone begins to ring, is a melancholy evocation of loneliness and a desire to belong, reinforcing the deeper theme that it’s vitally important to think through all the implications of the decisions we make and the potential consequences of our choices.

Forsyth has such a delicate touch and such obvious affection for all his characters and the actors playing them, that the underlying potential for darkness only becomes apparent with repeated viewings of the film … its full meaning makes it even more pertinent, and urgent, now than when it was first released. Its freshness makes it seem completely undated.

*

The disk

The 2K transfer used for Criterion’s Blu-ray does full justice to Chris Menges’ gorgeous photography which imbues the Scottish land and seascape with a kind of inner light, emphasizing its status as something very much alive, to be treated with care and consideration. The witty dialogue is clear and Mark Knopfler’s music delicately underscores both the comedy and the melancholy.

The supplements

Criterion have packed the disk with extras, mostly archival from the time of its original release. The two new contributions are a commentary with Forsyth in conversation with critic Mark Kermode and an on-camera conversation between Forsyth and critic David Cairns (16:17).

The archival pieces are four television shows largely focused on the production of Local Hero: The South Bank Show (1983, 52:31), in which Melvyn Bragg presents a making-of doc; another Making of “Local Hero” (1983, 52:19) produced for Scottish television; an interview with Forsyth, also made for Scottish television, and apparently culled from material shot for the longer program (1983, 26:04); and Shooting from the Heart (1985, 52:11), a documentary about cinematographer Chris Menges which covers his career as a documentary filmmaker as well as his work for various other directors in addition to Forsyth.

The sheer volume of this coverage indicates what a big deal Local Hero was for a nascent Scottish film industry in the early ’80s.

There’s also a trailer (2:24), and the booklet essay is by film academic Jonathan Murray.

Comments

I hadn’t noticed that this was out. Ordered.

I never thought of it as a whimsical trifle when I saw it in the theater when it arrived here in Minneapolis. It was discussed for a while after we saw it at the Uptown. That was the local theater that ran all sorts of foreign films. They had played Gregory’s Girl a couple of years before and I really enjoyed that. Gregory’s sister is my favorite character. You can’t even get a cheap DVD of it anymore.

I like all of Bill’s first three movies quite a bit. I recently bought the BFI Blu-ray of That Sinking Feeling but I haven’t bought an all-region Blu-ray player yet.

I liked Comfort And Joy, Housekeeping and Breaking In when they came out but not enough to revisit them in years. I don’t have copies of any of them.

That Sinking Feeling is an interesting movie, but you may need to use the subtitles!

One of my favourite Forsyth films is actually the one he probably got his worst reviews for, Being Human, which is one of the few movies in which I can stand Robin Williams.