Recent miscellaneous viewing

Once again, I’m way behind in my self-imposed aim to use this blog as a record of my (admittedly excessive) movie viewing. It’s an impossible task when I only have time to post once or twice a week. So over the next couple of posts I’ll try to squeeze in comments about a lot of movies I’ve neglected over the past few months.

Angry Young Men

I was born two years before England’s “angry young man” movement exploded with the first stage production of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (1956). That movement, a kind of cultural earthquake shaking up post-war Britain as the remnants of Empire disintegrated, manifested at the time of the Suez Crisis, which marked one of the last overt attempts by European powers to impose imperial control in the Middle East by military intervention. (That project would be taken up by the United States three decades later.)

By the time I was old (and conscious) enough to be aware of the Angry Young Men, they were already a historical rather than contemporary phenomenon, something I read about after the fact. My impression was that they were a literary movement rooted in class resentment, largely expressed through novels and plays; they aggressively asserted the right of the working class to assume a fully realized place in a national culture defined from the top down, a culture which had hitherto seen the working class as the butt of condescending jokes which confirmed the natural justification for their subjugation.

The very term “angry young men” should have signaled something else, something a little more specific – something all too apparent in my recent viewing of Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top (1959), based on John Braine’s 1957 novel, and Tony Richardson’s Look Back in Anger (also 1959), scripted by Nigel Kneale. These are very much dramas about angry young men, men driven by resentment that their origins have shut them out of social privilege. In the former, Joe Lampton (Laurence Harvey) does everything he can to climb out of his working class origins, first by hard work, but then by setting his sights on the daughter of a powerful industrialist. He pushes furiously against the idea that class divisions put her out of his reach.

The class issue is less clear in Osborne’s play. This is partly due to the casting of Richard Burton as Jimmy Porter, a college-educated man who, with his friend Cliff (Gary Raymond), has a barrow in the local market. As intense as Burton’s performance is, he’s incapable of embodying a working class persona as convincingly as Harvey.

What the two characters share in common is that they act out their anger and resentment through the women they’re involved with. Both are monstrous egotists who view these women in terms which prop up their own sense of self worth. Porter is physically as well as psychologically abusive to his young wife Alison (Mary Ure), making her the focus of his rage against a society he believes is unfair to him.

Lampton is less overtly abusive, rather using women for personal gratification and gain. Having just arrived in town to take up a job in the council office, he immediately declares that he’ll have Susan Brown (Heather Sears), but in the meantime he begins an affair with the unhappily married Alice Aisgil (Simone Signoret). Here class and personal inclinations complicate his life because he develops a genuine emotional attachment to Alice, which he betrays in order to possess Susan. He begins his climb from one class to the other by killing something in himself (and melodramatically causing the death of Alice).

The masculine perspective of these films imposes on the female characters gender oppression as onerous as the class oppression the men experience; there’s a largely unexamined misogyny in both of them … which is complicated by the fact that Ure and Signoret give deeply affecting performances, eliciting more sympathy today than the rather unpleasant male protagonists, who direct their anger not at their class oppressors, but rather towards essentially powerless women, punching down rather than up. The other two female characters – Claire Bloom as Helena in Look Back in Anger and Sears as Susan in Room at the Top – are problematic in other ways.

Susan remains naively romantic, happy to become Lampton’s possession even though he really no longer wants her; all he wants is the social position she brings with her. Helena is more irritating. Alison’s friend, she’s a more experienced and sophisticated woman, an actress who visits while she’s in town for a show. She’s wise to Porter and they openly despise each other. Yet inexplicably, when the pregnant Alison goes back to her parents, Helena and Porter embark on a passionate affair. I guess her previous antagonism was rooted in his unavailability and that his monumental “authenticity” makes him sexually irresistible. This seems more like a young author’s fantasy than a plausible psychological narrative turn. In other words, another facet of the underlying misogyny.

Both movies are on Blu-ray from the BFI, Room as a stand-alone dual-format release, Anger as part of the nine-disk Woodfall: A Revolution in British Film box set. The transfers are excellent and extras plentiful.

*

German Cinema

I just re-watched Rudiger Suchsland’s two documentaries about German film from 1918 to 1945, From Caligari to Hitler (2014) and Hitler’s Hollywood (2017), on Eureka’s double-feature Blu-ray, and my reaction was pretty much the same as the first time I watched them a year or so ago: a combination of fascination and irritation. The former because the history of German film is so rich and both docs are packed with enticing clips from dozens of movies, the latter because they’re so overstuffed that too often you barely get to register something before Suchsland has already moved on to make two other points. It’s a case of trying to cover too much ground in too little time.

As indicated by the first film’s title, Suchsland pretty much accepts Sigfried Kracauer’s thesis that Weimar Cinema was an expression of national psychology, revealing an inherent desire in the wake of the First World War for an authoritarian state which would replace the chaos of individuality with the social order of Fascist control. While Kracauer’s work is full of interesting observations and illuminating readings of individual films, it needs to be remembered that he was looking at the period with hindsight amplified by the horrific events which had followed the collapse of the Weimar Republic, and in full knowledge of the Nazis’ genocidal project.

Post World War Two, Kracauer looked back to find evidence and an explanation for the national insanity. Conveniently, the period from 1918 to 1933 was framed by two films which dealt with madness and the ambiguity of institutions purportedly representing order – specifically, insane asylums. In both Robeet Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), the world is presented as a madhouse in which the separation between doctor and inmate is erased. Lang’s film was banned by the Nazis because it could so easily be read as a satirical attack on them and their leader. Mabuse, in his padded room, maniacally writes his “testament” just as Hitler wrote Mein Kampf in his prison cell … a testament which, like Hitler’s book, provides the blueprint for a madman’s control of society.

But the problem with taking Kracauer’s thesis completely seriously is that Weimar Cinema was too rich and varied to fit into such a tight box. The ’20s were a period of explosive energy and innovation in the new art form, capable of both epic entertainment and intimate psychological exploration. Yes, it could appeal to fascist tendencies in the mass audience, but it could also expose the social and political forces which were making life so difficult for so many. Suchsland’s documentary recognizes that the actual films offer a richer, more varied, less containable expression of national culture, but nonetheless, like Kracauer, the filmmaker finds himself compelled to see in them inevitable signs of the coming political madness.

Given this, it might be predicted that the follow-up documentary about Nazi-controlled movie-making would be less conflicted. And yet even under Joseph Goebbels’ ministry (he controlled everything from scripts to casting) cracks showed. There were, of course, the big, prestigious propaganda films – most notoriously Veit Harlan’s Jud Suss (1940), specifically designed to prepare the population for the coming Holocaust – but the majority of movies made under the Nazis were entertainment, distractions for a population whose existence was becoming more constrained as war came to dominate society.

There were light comedies, musicals and romances alongside the overt propaganda of movies like Hitlerjunge Quex (1933), in which a boy fearful of the chaotic freedom of the Left finds a comfortable home among the tightly controlled Nazis. Even there at the beginning of the period, a key element of Nazi psychology is laid bare, with the boy dying a noble death beneath the Nazi banner, his sacrifice pointing the way forward for his companions. The Nazis were a death cult, everything about their worldview (in retrospect) pointing not only towards the genocidal destruction of perceived enemies, but also to the glory of self-destruction. At the end, Hitler was determined that the entire German nation must die with him. In fact, the noble death of the nation was actually the subject of the last epic production of the regime, Veit Harlan’s Kolberg (1944).

But there are hints along the way which suggest that Cinema could not be so tightly contained – some works, initially approved by Goebbels, had to be suppressed after completion, while others seem to have been able to suggest some criticism of the regime. For instance, from what I’ve read, G.W. Pabst’s Paracelsus (1943), a biopic of the 16th Century physician who tried to introduce some scientific method into a moribund medical establishment, is a fairly standard representative of a genre which appealed to Hollywood in the ’30s and ’40s, but the clip shown in the doc is visually striking and, at least here in isolation, appears to show the uniformity imposed by Nazism as a kind of madness. Was this a subtle dig at Pabst’s bosses? Impossible to say without seeing the whole film. (There is a DVD available from International Historic Films, whose release of Kolberg I have, but it’s fairly expensive.)

Despite this possibly subversive scene, Paracelsus was passed for distribution by Goebbels. Strangely, however, Helmut Kautner’s Unter den Brucken (Under the Bridges, 1944) was banned. This seems odd from our perspective because it’s not overtly political. But that was the very problem for the Nazis; it was too personal, too intimate, too “civilian” as Suchsland’s commentary puts it. Given that so many films in the Third Reich were intended to provide entertaining distractions for a populace under increasing stress from the war, what might it have been about Kautner’s film that caused offence? Although there is an English-friendly German DVD available (again, quite expensive), I found a copy on the Internet Archive with decent subtitles and a watchable image and discovered, as the clips in the documentary suggest, that it is reminiscent of Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934). This is obviously partly due to its being set on a barge, but also because of its tone of melancholy romance – though, while Kautner’s work is atmospheric, it’s more naturalistic than Vigo’s almost mystical visual poetry. Two friends who jointly own a barge help a woman they suspect was planning to jump off a bridge, each of them falling in love with her, though they both keep misjudging her. The narrative is structured by the emotional complications which result from the various misunderstandings among the three until they finally settle into a three-way relationship with which they are all comfortable.

The fascinating thing about Unter den Brucken, quite apart from its charm and the easy-going performances of Hannelore Schroth, Carl Raddatz and Gustav Knuth as the trio, is the fact that, while shot late in the war when Germany was being smashed by Allied bombardment, there’s no trace of the destruction. The film has a languid pace, presenting a world at peace in which the small emotional concerns of these people are of great importance. It is utterly antithetical to the fanaticism of the Nazi regime without ever needing to address it overtly. While the filmmakers’ ignoring of the situation surrounding the production might seem irresponsible, it can also be seen as a powerful act of defiance, a refusal to acquiesce in the headlong rush towards self-destruction by affirming the value of ordinary lives and the essential decency of people. No wonder it was banned until after the war.

While I feel that any coherent thesis eventually gets lost beneath all the evidence gathered in both of Suchsland’s documentaries, all the clips he’s assembled here inspire a desire to revisit films already seen, but also frustratingly stir up a desire to see many others which remain out of reach – the “small” movies made during the Third Reich, those musicals and comedies and melodramas – while paradoxically copies of the pernicious Jud Suss and big-budget spectacles like Kolberg and Josef von Baky’s Munchhausen (1941) are available.

*

Quatermass

It should be clear to anyone who has followed this blog over the years that I’m a big fan of Nigel Kneale’s work, particularly the Quatermass trilogy, originally written for the BBC in the 1950s and adapted for the big screen by Hammer – the first two serials by Val Guest in the ’50s, the third by Roy Ward Baker in 1967. The first feature, The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), was brought to Blu-ray by Kino Lorber at the end of 2014, but it’s taken almost five years for the other two to arrive, with commentaries and extras, from Shout! Factory.

The third serial (and feature) is the most complex and thematically rich, but I’ve always had a particular fondness for Quatermass II (serial 1955, feature 1957), perhaps because it was the first one I saw … on television when I was about ten. But it’s also because it’s such a tight story of political paranoia, an English Invasion of the Body Snatchers cast on a (low budget) apocalyptic scale. You still have to make some allowances for Brian Donlevy’s blustering performance as Quatermass, but Kneale and director Val Guest do a fine job of compressing the three-hour serial down to a fast-paced 85 minutes.

Although I had high hopes for the hi-def upgrade from Anchor Bay’s old DVD, I have to admit that I was a bit disappointed by the transfer. Scanned in 2K from an archival print, unfortunately not from the negative (which I assume no longer exists), to my eye there are issues with the contrast, with a lot of detail in darker scenes lost in dense blacks. (Gary Tooze at DVD Beaver doesn’t agree with me, and strangely the frame grabs on that site look much better than the movie looked in-motion on my TV.) The disk has three commentaries – two new, one archival (the latter with Kneale and Guest) – an archival interview with Guest, and two very brief interview clips with crew members.

No such qualms about the Quatermass and the Pit (1967) disk. The transfer is virtually flawless. This was not only Roy Ward Baker’s best film for Hammer, it ranks up there with his greatest work, A Night to Remember (1958). Adapted by Kneale himself, the distillation of his complex serial – which encompasses all of human evolution, the origins of superstition and religion, the underlying reasons for tribalism and our endless penchant for violence and war, with a Martian invasion thrown in – retains pretty much every important note from the original.

What I miss here from the first two films is Guest’s grittiness, the urgency his documentary-like approach adds to those stories. In colour and shot largely on sets, Pit is more of a movie-movie. But within that context, it’s one of the finest pre-2001 science fiction films, undercut only slightly by some effects which were hampered by Hammer’s inadequate resources (the vision of the Martians’ self-genocide demands a great deal of viewer suspension of disbelief). On the other hand, the cast is excellent, with Andrew Keir much closer to Kneale’s conception of Quatermass as the epitome of scientific reason than Donlevy’s pushy loud-mouth.

Again, Shout! Factory have loaded the disk with three commentaries and a large collection of interviews, both new and archival. Also included on both disks is the same old episode of the 1990 series The World of Hammer dedicated to the company’s sci-fi productions.

*

Fantomas

I love the silent serials of Louis Feuillade. It’s no wonder the Surrealists admired him; his episodic stories of master criminals, elaborate conspiracies and intrepid heroes transformed France and its bourgeois culture into an oneiric landscape of danger, romance and adventure. From Fantomas in 1913, through Les Vampires (1915), Judex (1917, and again in 1918), and Tih Minh (1918), Feuillade created what feel like free-form, improvisational meditations on the corruption and hypocrisy of a society where crime is an enterprise like any other business, just better organized and more far-reaching. Much of the action was filmed in real locations, which now gives the films a fascinating documentary dimension.

Feuillade’s dreams have haunted French Cinema. His influence can be traced through the poetic realism of the ’30s on up to the ’90s and Olivier Assayas’ wonderful Irma Vep (1996), in which a director tries and spectacularly fails to recreate Feuillade’s themes and aesthetics in contemporary Paris. In the 1960s there was a brief surge of Feuillade references, beginning with Georges Franju’s Judex (1963). Franju’s film is an unabashed homage, shot in black-and-white with a self-consciously poetic visual style; but it wasn’t his first choice for a remake. He really wanted to do Fantomas, a much darker subject centred on a master criminal rather than a do-gooder vigilante. Unfortunately for Franju, the rights to the Fantomas character (created by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre in 1911 and running through 43 novels until 1963) were owned by someone else.

When a series of three Fantomas movies were made between 1964 and 1967, they were directed by Andre Hunebelle (from scripts by Jean Halain and Pierre Foucaud) and starred Jean Marais in the dual roles of intrepid reporter Fandor and the masked supervillain Fantomas. But they were made in the wake of the international success of James Bond, at a time when pastiches were appearing in growing numbers – in France the OSS 117 movies, in the U.S. Matt Helm and Derek Flint, and so on. In Hunebelle’s trilogy, tongue is firmly in cheek, and the action (some pretty impressive stunt work) and adventure is leavened with an increasing amount of comedy – more Clouseau than Feuillade.

Shot in colourful widescreen, the films are lightweight entertainment with good casts and plots loaded with complications (Fantomas is a master of disguise who can frame his opponents by committing spectacular outrages while wearing their faces). Fantomas himself, with his synthetic blue face, is an engaging visual effect; Marais is a solid hero and Mylene Demongeot an appealing heroine as Fandor’s girlfriend Helene. And then there’s Louis De Funes. An actor with obvious comic skills, his portrayal as Commissioner Juve tips the series increasingly into the territory of farce.

In the first film in the trilogy, Fantomas (1964), Fantomas is annoyed by a fake interview written by Fandor which makes him seem ridiculous, so he commits a spectacular crime disguised as the reporter – it’s personal. In the second film, Fantomas Unleashed (1965), things escalate with the villain kidnapping scientists to help him create a doomsday weapon with which, in the pointlessly grandiose way of supervillains, he intends to destroy the world. In the third film, Fantomas vs Scotland Yard (1967), his plans are scaled back to a mere money-making protection racket through which he targets the world’s richest men (industrialists and criminals).

This last film replaces the world-threatening action of the previous one with the generic tropes of an old dark house story, complete with fake ghosts, with most of the action taking place in a Scottish castle. In addition to the smaller scale, apparently feeling that De Funes’ buffoonish Commissioner Juve is as big an attraction as Fantomas himself, the filmmakers give the policeman a more central role, his comic shtick pretty much overwhelming the rest of the movie. While the cartoonish stakes of Fandor’s pursuit of Fantomas in the first two films were a matter of generic convention, they did drive the narratives. In the third film, it all devolves into outright self-parody, virtually mocking the audience for having been entertained by the previous movies. De Funes, for all his personal appeal, quickly becomes an irritating distraction from what is already a very thin plot.

It doesn’t seem surprising that the series ended here, the writers and director having obviously exhausted the potential of their parodic approach to the material. But overall, the trilogy is an entertaining exercise in comic adventure which bears some resemblance to Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik (1968). All three films look attractively colourful on Kino Lorber’s two-disk Blu-ray release. The only extra is another information-packed commentary from the busy Tim Lucas on the first film.

Comments

Thanks for the insight and context on “angry young men.” I’m watching Look Back in Anger as I write and I just saw Room at the Top about a year ago.

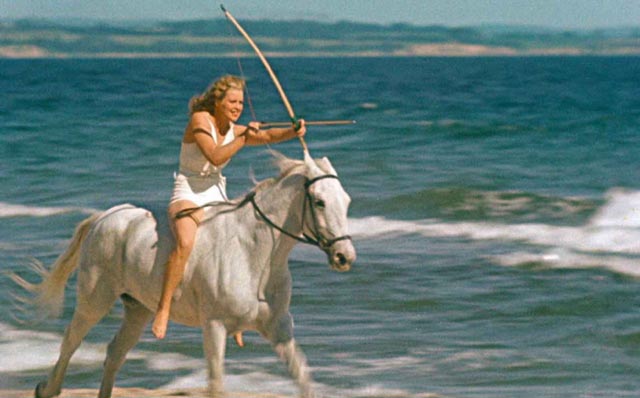

No Zarah Leander above; the still is showing Marika Rökk in “Die Frau meiner Träume”.

Corrected… image replaced