Recent miscellaneous viewing, part two

BFI

I recently watched two BFI releases, both films I was previously unfamiliar with, and both by coincidence with a Scottish connection.

Blue Black Permanent (Margaret Tait, 1992)

I didn’t know anything about Scottish poet and filmmaker Margaret Tait until the BFI released Blue Black Permanent (1992), her sole feature, made towards the end of a four-decade career as a documentary and experimental filmmaker. Having studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and joined the Royal Army Medical Corps during the War, she moved to Rome and studied film at Italy’s famed Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in the early 1950s. Returning to Scotland, Tait formed her own small company, Ancona Films, and eventually made more than two dozen films on the fringes of the small Scottish industry.

She was in her 70s when she made Blue Black Permanent, a poetic, allusive meditation on art, memory and the strangely unknowable connections between parents and children. With its dreamlike shifting back and forth in time, I confess it took a bit of effort to keep myself oriented. The film is framed by the efforts of middle-aged Barbara Thorburn (Celia Imrie) to come to terms with and understand her mother, who died (possibly a suicide) when Barbara was still a child – she is now older than her mother was when she drowned on the shore of one of the Orkney Islands. As Barbara digs into her own memories and talks to her sometimes inattentive partner Philip Lomax (Jack Shepherd), Tait gives us fragmentary glimpses of the mother’s life.

These layered flashbacks range from Greta Thorburn (Gerda Stevenson)’s troubled adulthood in Edinburgh as a wife to Jim Thorburn (James Fleet) and mother to two children, who struggles to be a poet, to her childhood in the Orkneys where she feels a mystical connection to the land and sea. Although it may have been a deliberate creative choice, the scenes with Imrie and Shepherd feel overly theatrical and claustrophobic in comparison with the visually freer flashbacks – rain-drenched Edinburgh streets, the studio of painter Andrew Cunningham (Sean Scanlan), and most importantly the rugged landscape of the Orkneys. Barbara’s life is cramped, while the life she imagines for her mother is suffused with an idealized romanticism and a tragic sense of unfulfilled potential.

While it might be fair to say that Tait’s presentation of the artist as a lost and tortured soul is trite, her evocation of Greta’s island childhood is nostalgically appealing. But at its deepest level, Blue Black Permanent is about how we as children can never fully know who our parents were as individual, living, feeling people who existed in complicated ways outside their connection to us. In trying to create a comprehensible image of her mother, does Barbara see creativity as a form of madness, or does she interpret madness (and try to calm her own fear and confusion) as a form of creativity? This ambiguity is maintained by giving us no access to Greta’s poetry; we’re told she had a few published in local newspapers, but there’s a shot late in the film, after Greta’s death, when Jim takes the grieving children away from the island and Barbara glances back to see her mother’s notebooks left behind on the table by the window. What had seemed so precious to Greta is of no consequence to Jim and what she had tried so hard to create is abandoned without a thought, apparently meaningless to her husband, but an unresolvable source of mystery to Barbara.

*

Long Shot (Maurice Hatton, 1977)

Very different is Maurice Hatton’s Long Shot (1977), a gritty black-and-white dead-pan mockumentary about the struggles of a producer (of documentaries and commissioned films) and writer to get a dramatic feature off the ground. Producer Charlie (Charles Gormley) and writer Neville (Neville Smith) travel to Edinburgh for the annual film festival hoping to persuade Sam Fuller to take on Gulf and Western, their satirical project about the Scottish oil boom. As they alternate between hashing out script problems in their rented rooms and running around the city trying to get meetings – they never do connect with Fuller, but spend some time with Wim Wenders (at the festival for a screening of The American Friend) and various other people, some involved with film, some just “civilians” – Hatton shows the exhausting effort it takes for a small-time independent to mount even a low-budget feature.

Charlie is committed and enthusiastic, but even he begins to wear down as each new potential advance requires some kind of compromise; the higher he goes – he ultimately has meetings with Sandy Lieberson, an executive with a major American distributor, and director John Boorman, who would like to reshape the script to suit his own creative needs – the more he seems to be facing some kind of defeat, losing control of the property he has initiated.

Long Shot, shot by several cameramen using short ends of multiple different 16mm film stocks, has a bleak, grainy look which gives its low-key comic perspective a decidedly melancholy tone, only slightly offset by a brief colour coda in which Charlie makes it to Hollywood – the context makes this seem more like a wishful dream than the successful fulfillment of his ambitions.

Both disks have a number of extras – three of Tait’s short films, an interview with her plus a panel discussion of her work; a short by Hatton starring Susannah York, a playful portrait of Edinburgh with Sean Connery as guide, and an interesting and humorous documentary about the Edinburgh film festival with Robbie Coltrane as guide – and both films have been given fine transfers from the original 16mm negatives.

*

Twilight Time

The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915)

Writing about the issue of race and racial masquerade in a recent post, as well as watching Rudiger Suchsland’s two documentaries about Weimar and Nazi Cinema, made me finally take a look at the Twilight Time Blu-ray of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), which has been sitting on the shelf for about a year. I think it’s about sixteen or seventeen years since I last saw the movie (on DVD as part of Kino’s Griffith Masterworks box set), and I had to brace myself to tackle it again. It’s interesting to note that while so many of the films made by the Nazis remain suppressed, Griffith’s film retains its status as a landmark in film history despite being one of the vilest and most pernicious movies ever made.

Woodrow Wilson called it “history written with lightning”, but the history it supposedly presents is a mass of dangerous lies in the service of an ideology of white supremacy which has resurfaced with a vengeance a hundred years after the movie was made. Basing the film on a couple of novels by arch segregationist Thomas Dixon, Griffith presents the romanticized view of the South which has held sway in America’s self-mythology for two centuries. The South is a land of bucolic gentility populated by a well-bred white aristocracy and happy, well-cared-for slaves, while the North is full of malignant abolitionists determined to crush paradise for some inexplicable reason.

A movie which paints abolitionists as villains and the terrorist Ku Klux Klan as noble and heroic is obviously problematic, but what gives Griffith’s skewed history its dramatic force is his utterly egregious treatment of Blacks as sinister, mentally deficient and animalistic – or rather, Blacks under the sway of Northern influence, because the house slaves of the Cameron family remain loyal and despise the interlopers who have come to disrupt their own happy idyll. The racism is made worse by having most of the Black characters played by whites in blackface, as exaggerated as performers in a minstrel show.

In Griffith’s history, Blacks are irredeemably corrupt. But during Reconstruction, they attain complete social and political power. Through fraudulent control of elections they seize the legislature and pass laws in their own favour (including legalizing miscegenation). Blacks are determined to crush white society and, of course, seize white women. Griffith’s vision of the post-war South raises the spectre of what is now touted as “white genocide”. The absurdity of this assertion that freed slaves immediately attained absolute power over the South is obvious, but it’s a myth which was necessary to justify the brutality of the white South in restoring the “rightful” order of white dominance … to justify decades of lynching, of Jim Crow, of brutalization and segregation. And it lingers on to the present day because after the Civil War there was nothing equivalent to Germany’s de-Nazification to excise the pernicious social and political attitudes which underlay a society built on centuries of slavery. Rather than using the war as a means to produce a deep reformation, the victorious Union pulled back and allowed the rot to fester.

In fact, the rot permeated the rest of American culture; the slave-owning South retained a romantic allure, a vision of a perversely enticing mythic past – exemplified by the perennial popularity of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind and David O. Selznick’s 1939 film adaptation. Even 150 years after the war, the U.S. still hasn’t come to terms with its history and the fact that it was built as a great economic power largely on a system predicated on owning human beings as property. The attitudes embedded in Griffith’s epic still run through a large segment of American society.

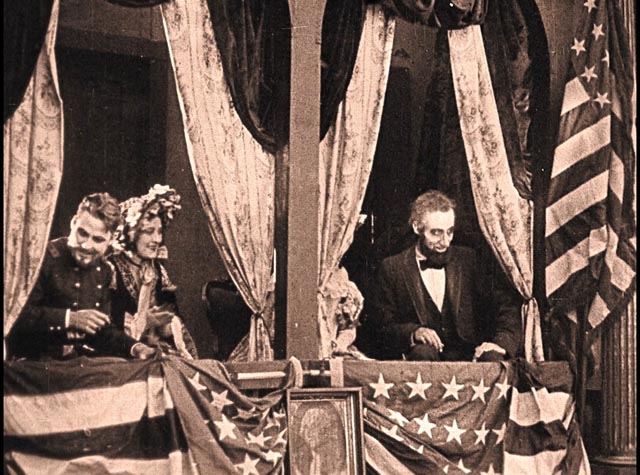

And yet despite the perniciousness of The Birth of a Nation, it stands in its complexity and technical accomplishments as a landmark in the development of film. Griffith used every device which had been created during the medium’s first two decades, combining them in ways which expanded the possibilities of visual storytelling. His chief innovation was to get them all to work together through his elaboration of editing – close-ups and panoramic vistas, tableaux and tracking shots, multiple characters and narrative threads presented in parallel and gradually converging. In this sense, The Birth of a Nation is a synthesis of all the possibilities of cinema, a monumental leap ahead … but a leap made in the service of a great lie which perpetuated a great social evil; the movie drew wide protests when it was released, but it also provided inspiration for the resurgent Klan which was embarking on new waves of terrorism and murder.

Watching it again, I found my attention flagging as the third hour ground on towards the supposedly rousing finale with the spectacular ride of the Klan to the rescue and the restoration of the natural order of white dominance and Black repression … it’s possible to appreciate Griffith’s achievement by watching the first half which climaxes with the assassination of Lincoln, but that achievement gets lost in the second half as it’s buried by the increasingly repulsive content.

In her booklet essay, Julie Kirgo mentions that the Twilight Time staff debated the wisdom of releasing this edition, particularly given the current resurgence of white supremacy, but it was decided that the film’s historical importance warranted the effort. The company has done a reasonably good job of providing context – there are four-and-a-half hours of extras on the two-disk set, including a couple of featurettes on the historical distortions of the film, outtakes and camera tests, brief filmed introductions to both parts from a 1930 re-release with Griffith speaking about “the truth” of his work, a featurette on recording the score, a brief audio clip of Griffith speaking to Cecil B. DeMille, and several text pieces about the film’s history and the restoration.

There are also three silent shorts with Civil War settings, plus Thomas Ince’s feature The Coward (1915). The latter is particularly interesting because, by comparison, it highlights Griffith’s innovations. Although made and released almost simultaneously, The Coward was shot with a mostly static camera, with almost no cutting within the scenes – when there are edits, it’s only to go to a quick insert of a detail which needs highlighting or, much more rarely, to a medium close-up of a character. The static style gives the film a lugubrious pace, each individual moment of action kept on screen too long. Griffith had obviously moved far beyond this standard technique of visual storytelling.

While the best-made of the shorts is Thomas Ince’s The Drummer of the 8th (1913), the most interesting is Griffith’s own The Rose of Kentucky (1911), the only other film he made featuring the Klan; but here they are the villains, violently attacking a decent white tobacco farmer who has declined to join them. The image is completely at odds with the heroic depiction of the Klan in the feature just four years later. There’s insufficient evidence to draw any particular conclusion, but it should be noted that the short avoids any indication of the Klan’s aims, depicting them as bad guys only because they are attacking a white man – whom they end up respecting because of the fight he puts up. Without any notable Black presence, the film avoids racial issues altogether.

*

After tackling Griffith’s feature, I watched Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation (2016), whose title obviously positions it as at least in part an answer to Griffith’s racist argument. Setting aside the personal issues which clouded its release, Parker’s movie turns the older film on its head. In telling the story of Nat Turner and the brief revolt he led in 1831, Parker presents the slaves as a vibrant society populated by fully realized people possessing rich social, psychological and emotional lives under the perpetual shadow of threatened – and frequently real – violence. The slave-owning society, however, comprises a socially, psychologically and politically indefensible population of vile moral degenerates, irredeemably deformed by their practice of owning and abusing other human beings. The plausible suggestion here is that the excessive violence inflicted by the white owners on their Black possessions stems from the enormous effort required to suppress an always-ready-to-surface awareness of the great moral crime on which their lives rest. The intensity of the racism embedded in American society points to this repression, turned outwards in order to avoid dealing with it honestly.

The fact that there is still a widespread desire to view the antebellum South through a romantic lens is really disturbing – something like Germans looking back nostalgically at the time of death camps and the Holocaust.

*

The Vanishing (George Sluizer. 1993)

I had always avoided George Sluizer’s American remake of his international hit Spoorloos (The Vanishing, 1988), because it seemed redundant and because too often American remakes of foreign films are compromised. From what I read at the time, this seemed to be the case – the original film’s chilling ending, an existential nightmare, was changed to let the hapless hero off the hook, while meting out a just punishment to the villain. But some time ago, I read something favourable about the remake (I think it was in Jonathan Rosenbaum’s Cinema-Scope column) and I ordered Twilight Time’s Blu-ray … which ended up sitting unwatched on the shelf for more than a year.

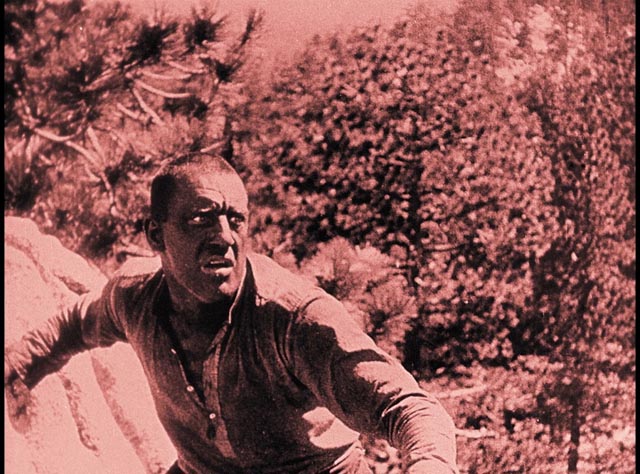

Well, I finally did watch it and my impression is ambivalent. While it sticks fairly close to the original for the first two-thirds, it does pull back from the awful horror of the original ending. And yet, the script by Todd Graff finds an interesting way to wriggle out of the nightmare which adds a whole new thematic level to the story. In the original, we get a devastating cat-and-mouse game between two obsessed men, with the death of a woman as the factor which inexorably ties their fates together. In the remake, however, a second woman is introduced, one who becomes the active agent who breaks the murderous psychological bond between the cold-blooded killer and the man driven to a kind of insanity by his need to overcome the crippling effect of not knowing what happened to his girlfriend.

This change shifts the movie from chilly existential horror to melodrama, but Sluizer makes it work, thanks in no small part to the performance of Nancy Travis as a strong, independent and determined woman who possesses a much firmer grasp of reality than Kiefer Sutherland’s psychologically wrecked protagonist. Spoorloos is a gripping thriller set in an unpleasantly misogynist universe; the remake turns this on its head, exposing male violence as a sign of weakness masquerading as strength. This elaboration, however, does dilute the horror of what the killer did to the girlfriend and now tries to repeat with the protagonist, a horror which is central to the power of the original.

The cast is very good – including Lisa Eichhorn as the killer’s wife, Maggie Linderman as his daughter, and Sandra Bullock as the unfortunate victim – but Jeff Bridges as the murderous sociopath is irritating. For some reason he chose to use an unidentifiable, highly affected accent which continually distracts attention from what’s going on. There’s really no explanation for it.

*

The Valachi Papers (Terence Young, 1972)

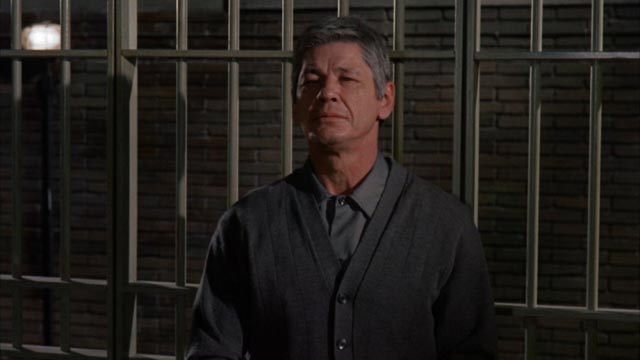

It was the misfortune of Terence Young’s The Valachi Papers (1972) that it was produced and released simultaneously with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Both films dealt with virtually the same material, though one was based on the testimony of a participant while the other was based on a novel (for which that testimony was an important source). There are two main differences between the films: first, The Valachi Papers is viewed from the perspective of a mob foot soldier while The Godfather deals with mob royalty; second, Young’s movie attempts a just-the-facts documentary account of several decades of life in the mob as it strives to attain a kind of capitalist respectability, while Coppola’s film, of course, constructs a great romantic myth about that same trajectory.

Joe Valachi (Charles Bronson), betrayed by his own boss (Lino Ventura), spills the beans to a federal investigator about his three decades as a driver and hit man for the mob. Bronson gives one of his best performances as a man who becomes involved because he simply wants to belong, to be part of a big “family” which looks after him in return for his loyalty and willingness to do violent things without hesitation. But as time passes and the mob bosses strive to become “businessmen”, that unwavering loyalty is reciprocated less and less … until Joe finally transfers his allegiance to the authorities and provides what was at the time the first really detailed account of the inner workings of the Mafia.

Compared to The Godfather, The Valachi Papers is a dogged, old-fashioned movie, closer to Roger Corman’s The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967) and Budd Boetticher’s The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960) than to Coppola’s grand opera. The cast is good, but its focus on process doesn’t provide a lot of room for character.

The only extras on The Valachi Papers and The Vanishing’s Blu-rays are isolated score tracks.

Comments