Stanley Kramer and the limits of liberalism

Stanley Kramer was an unabashed liberal and he wanted everyone to know it. From the beginning of his career – first as an independent producer, later as producer-director – he was quite open about making movies which would convey a progressive (for the time) social message. It was this eschewing of subtlety that irritated critics, even as many of his productions were box office successes. Audiences weren’t as picky about getting a lecture with their entertainment as the industry tended to think.

It was Kramer’s commitment to social causes that made him tackle “big” subjects – racism, the Holocaust, right-wing attacks on science and reason, nuclear war. This was also what gave his movies, particularly as a director, a ponderousness, wearing their good intentions very visibly on their sleeves. But at the same time they displayed a level of craft equal to the best the big studios were capable of, and – more importantly – he had a real flair for casting and was often an excellent director of actors. In fact, the performances went a long way towards overcoming the movies’ various shortcomings.

I actually like quite a few of Kramer’s films, a feeling reinforced by recently watching three of his productions (two of which he also directed) over a couple of days. Despite the criticisms which follow, I did enjoy watching all three on fine Blu-rays from Indicator.

*

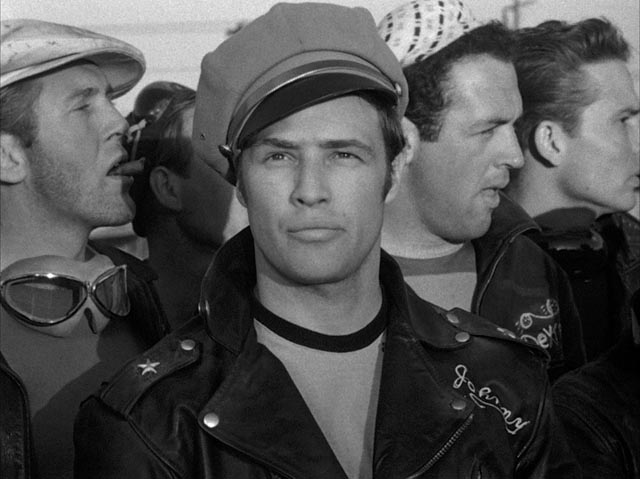

The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1954)

Based on an actual incident which happened in a small California town in 1947, The Wild One was the third movie Kramer produced in 1953, after Edward Dmytryk’s The Juggler (with Kirk Douglas as a Holocaust survivor in the newly-formed Israel) and Roy Rowland’s Dr. Seuss-scripted The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T … which if nothing else indicates Kramer’s eclecticism. Directed by Hungarian emigre Laslo Benedek, who had previously made the very different Death of a Salesman (1951) for Kramer, it was a key film in consolidating Marlon Brando’s status as a brooding Method star (his next film would be Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront [1954]).

Looked at today, it takes a little effort to understand why The Wild One was so controversial when it was released. It was even banned in England until 1967. Biker gangs were a phenomenon which emerged from post-War unrest; many were largely composed of young men who had a hard time readjusting to civilian life after their experiences in the war, the gangs providing both a sense of excitement and the kind of group identity they had experienced in the military. With individualism submerged in the gang, there was a feeling of freedom which could easily devolve into lawlessness and violence … which is apparently what happened when thousands of bikers descended on Hollister and wreaked havoc over that weekend in 1947.

It seems that one of the main sources of the controversy over the movie was its refusal to draw clear lines between order and lawlessness, and particularly the way it pushed against the Production Code by not ultimately punishing bad behaviour with any clearly defined retribution. The fear was that it would inspire copycat violence because it didn’t depict the righteous wages of sin. Those were simpler times!

The Wild One now seems a bit dull, its initial display of anarchy devolving into a psychodrama about the inner pain of a lonely, fearful youth (the 28-year-old Brando) who strikes out at the world because he can’t articulate his own sense of alienation. Johnny Strabler (Brando) leads his leather-clad gang over empty highways, evoking an illusory sense of freedom which ultimately finds its paltry expression in pointless acts of vandalism whose only apparent purpose is to frighten the inhabitants of a small town.

The movie (scripted by John Paxton) roots itself in memories of westerns in which frontier towns are plagued by gangs of outlaws. Here, the local sheriff (Robert Keith) is a weak and ineffectual symbol of an order which manages to maintain itself only because the community is homogeneous. When a disruptive outside force arrives to threaten that order, he doesn’t have the resources to deal with it and retreats into a bottle while the gang tear up the town.

This set-up seems to present a simple dichotomy, but the emphasis settles on Johnny himself, seeking sympathy for him by psychoanalyzing his alienation – with the help of sweet, understanding Kathie (Mary Murphy), who can see through the bravado to the frightened child within – and in the second half, it’s the fine upstanding citizens who take the brunt of the film’s criticism (echoing the townsfolk in Kramer’s High Noon [Fred Zinneman, 1952]). Taking the law into their own hands, they grab Johnny and beat the crap out of him – the only physical violence in the film; the gang only target property. These citizens are also responsible for the death of an old man towards the end, when a thrown tire iron knocks Johnny off his bike as he tries to escape, sending the riderless machine up on to the sidewalk where it hits the man.

In pleading for understanding of Johnny and condemning the vigilante actions of the intolerant townspeople, The Wild One ends up somewhat confusing, the late stage violence essentially erasing the gang’s earlier destructive behaviour. In trying to create some kind of nuanced point of view, it all but excuses Johnny’s antisocial behaviour because it comes from deep inner pain, while condemning the citizens because their behaviour is rooted in prejudice and intolerance.

While its plea for liberal understanding is confused, The Wild One is efficiently directed by Benedek (who went on to a long career in television, with only a few subsequent features, the best being the odd Swedish-American Gothic thriller The Night Visitor [1971]), atmospherically shot by Hal Mohr, and well-acted by a cast which includes Lee Marvin, Jay C. Flippen, Jerry Paris and Timothy Carey. And then, of course, there’s Brando, whose Method at this distance seems rather mannered and overwrought. But he does create a powerfully iconic image in those leathers astride a big Harley.

*

in Stanley Kramer’s Ship of Fools (1965)

Ship of Fools (1965)

If The Wild One looks like an ambitious B-movie, Ship of Fools (1965) is a prestige A production all the way. One of Kramer’s most accomplished films as a director, its ultimate pessimism seems almost to defeat his best liberal instincts. Coming between the two bloated and problematic comedies It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), it’s almost as if he lost control of his pent-up seriousness.

Based on Katherine Anne Porter’s award-winning doorstop of a novel, Kramer’s adaptation (scripted by Abby Mann) is suspended somewhere between high drama and soap opera, heavily freighted with over-obvious ironies and stuffed with great performances. While it might raise an occasional groan, it’s never less than entertaining and at times becomes genuinely moving as it weaves its way through multiple story threads involving the passengers and crew on a German liner sailing from Vera Cruz to Hamburg in 1933. These people are all so preoccupied with the emotional and social concerns of their own lives that they remain largely blind to the looming global catastrophe signaled by the date.

As you’d expect with such an ensemble piece, some stories are more fully developed than others, some more interesting, some less. The weakest involves a “very serious” young artist, David (George Segal), who paints only the bleak nobility of the underclass, apparently hoping that his work might wake the conscience of the complacent rich. David is travelling with a rich young woman, Jenny (Elizabeth Ashley), with whom he has a passionate sexual relationship despite increasing friction about their class differences, brought to the surface when the ship takes on hundreds of poor Spanish workers being kicked out of Cuba, who are forced to live on the deck in squalid conditions. He feels a bit guilty about her paying for everything, and she’s tired of him painting ugly things when he’d be more successful if he aimed for beauty instead. As they learn during the course of the voyage, hot sex is ultimately insufficient to overcome fundamental social and political differences.

While this thread is a bit lifeless, at the other end of the spectrum is the film’s cartoonish villain, Siegfried Rieber (Jose Ferrer), a loud, boorish publisher with a very vocal enthusiasm for Fascism and the coming resurgence of German power and purity. At the Captain’s Table during meals, he advocates for the euthanasia of the mentally, physically and socially unfit. His hypocrisy is revealed when the young woman he’s openly having an affair with, Lizzi (Christiane Schmidtmer), learns that he’s married with children. Even worse, it turns out he’s not even an actual German, but was born in Austria (like another prominent Fascist of the time!).

At one point, Rieber smugly ejects Freytag (Alf Kjellin) from the table because he has learned that the man is married to a Jew, banishing him to a smaller table with other outcasts – Julius Lowenthal (Heinz Ruhmann), the one overt Jew we see among the passengers, a cheerful and optimistic salesman who loves Germany and its culture and believes the prejudices of people like Rieber can never take hold in such a great country; and Karl Glocken (Michael Dunn), a dwarf who has also suffered from a lifetime of prejudice and ridicule and has developed a warily amused cynicism about the human race as a result. In fact, the narrative is framed within his point of view (he directly addresses the camera at beginning and end) and Dunn gives the most engaging performance in the movie.

There’s also Vivien Leigh in her final role as Mary Treadwell, a wealthy divorcee struggling to cope with loneliness and aging, and Lee Marvin as Bill Tenny, a failed baseball player turned alcoholic who sees life as utterly unfair because he never got the one thing he really wanted (that baseball career). He has a crude and potentially violent attitude towards those around him, particularly dancer Pastora (Lydia Torea) whom he expects to have sex with after buying her champagne. Pastora tricks him by deliberately giving him the wrong stateroom number and Tenny drunkenly forces his way into Mary’s room; in the film’s one overt instance of violence, Mary beats the heck out of him with her shoe – it’s a painful scene not simply because of the rawness of the characters’ emotions, but also because it looks as if Leigh is inflicting genuine damage on Marvin (there were reports that she actually broke his nose).

Kramer juggles all these threads, and more, quite skillfully and the movie seldom loses its sense of racing headlong towards disaster. In a sense, it’s something like a disaster film in which everything is foreplay and the actual catastrophe never arrives, though right at the end it’s embodied in a single glimpse on the dock in Hamburg of a young man in uniform who turns and reveals a Swastika armband, letting us know if we hadn’t already figured it out that every one of these people with their individual problems is doomed to be swept away by the rising tide of history.

The authentic emotional core of Ship of Fools is also fraught with the heavy weight of doom. When the ship takes on the Spanish labourers, a woman is also brought on board, under police escort. This is La Condesa (Simone Signoret), a privileged woman who dared to stand up for the oppressed poor and now finds herself being exiled. A middle-aged drug addict, she is bitter about life … and yet finds herself drawn to the equally bitter ship’s doctor, Wilhelm Schumann (Oskar Werner), a man plagued by conscience and a defective heart. Both battered and wary, they find something in each other which for a while gives them hope. But it’s something neither has the strength to trust … their emotional bond can’t sustain them against that approaching tide. Here, Kramer’s liberal optimism fails him and Ship of Fools becomes his one genuinely pessimistic work.

Ship of Fools is also, on a technical level, his most impressive film. The ship itself was built on soundstages, the ocean in all its moods – rough and calm, shimmering in daylight, brooding under stars – was created through a superb use of process photography. This studio technique always carries the risk of breaking audience investment in the story by drawing attention to the artificiality of a movie’s illusion, but here the exceptional technical quality of Ernest Laszlo’s cinematography maintains the authenticity of the narrative space at all times.

*

R.P.M. (1970)

While it’s probably not surprising that a classical liberal might be depressed when contemplating the spectre of what Nazism wrought in the mid-20th Century, one senses a real defeat five years and three features later. Kramer followed Ship of Fools with a pair of heavy-handed comedies – the popular Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) and the bloated but inconsequential The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969) – and then turned to a matter of urgent concern: the social and political near-revolution which had been blowing the country up for the past few years.

I didn’t see R.P.M.* (*Revolutions Per Minute) when it was released in 1970. Actually, I seemed to miss all the campus revolution movies at the time, though in retrospect I’m not sure why I wasn’t interested. There were, in addition to Kramer’s movie, Stuart Hagmann’s The Strawberry Statement and Richard Rush’s Getting Straight, both also released in 1970. Maybe I was just not yet socially conscious … more likely to go see John G. Avildsen’s redneck-vs-hippies exploitation hit Joe (also 1970) than something ostensibly more serious. It was years later that I finally saw the era’s best ripped-from-the-headlines social commentary film, and the only one which still holds up as a serious examination of the time, Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969).

I did know about Kramer’s movie, though, because I was a big fan of Melanie and on one of her albums (I bought them all) were a couple of songs from the film’s soundtrack. And now, almost fifty years later, I’ve finally seen R.P.M., thanks to Indicator’s Blu-ray release. I doubt the lengthy wait makes much difference in terms of any appreciation of the movie, because it was already dated when it hit theatres.

To put it simply (simplistically) for the sake of argument, the essence of classical liberalism is reason, rooted in the changes brought about by the Enlightenment. It’s a view of the world which holds that observation and analysis can lead to understanding, and understanding can facilitate progress towards a better, fairer society. In this, liberalism requires a certain degree of stability and compromise to function … which is why it gets lost in times of extreme polarization (just look at what’s happening today).

The U.S., like much of Europe, had settled into a kind of comfortable complacency following the drawn-out economic recovery from World War Two. Throughout the 1950s, for the first time, national wealth was more fairly distributed, enabling workers to rise into middle class social and economic security. But that increased economic power had a corollary in the establishment’s fear of communism. If the formerly poor gained too much power, they might threaten those on top. The post-war Red Scare was a means of enlisting those lower down in the maintenance of the “natural” power of the establishment, a means which had the added bonus of justifying the global use of force to secure the economic interests of the wealthy and their corporations. (Racial oppression was another important component in maintaining “stability”.)

As internal stresses increased – the post-war generation chafed at conservative restrictions on their behaviour, personal and political – the war of aggression against Vietnam became the primary vehicle to assert American power and to contain the growing rebellion of the young. At least that may have been the poorly thought through plan. In the event, the war – and the draft – accelerated the rebellion, triggering a wholesale rejection of what the States claimed to represent. With the escalation of conflict – the anti-war movement drawing on and feeding into the Civil Rights movement – the country was fracturing along multiple fault lines. There were widespread riots, violent repression, assassinations, principled civil disobedience … and an establishment at odds with a growing number of disaffected citizens.

This was an environment in which liberalism became increasingly ineffectual. As Melanie’s lyrics put it: “Reason is the only way/To change what we’re creating/But reason sometimes turns into/Another word for waiting”. Kramer, a classical liberal, wanted to look at this situation specifically from his own point of view – not from either of the two polarized sides. No doubt he chose Erich Segal to write R.P.M. based on his counterculture cred as one of the writers of Yellow Submarine (George Dunning, 1968), although the release just three months after Kramer’s movie of Segal’s huge box office success Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970) might have served as a warning.

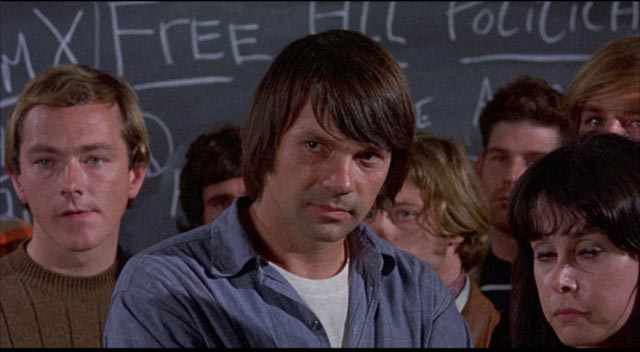

R.P.M. is set at a small college where a group of “radicals” have occupied the administration building in order to back up twelve specific demands. The group is led by Rossiter (Gary Lockwood), with a subset of Black students led by Steve Dempsey (Paul Winfield). Although there are women among the protesters, there’s no sign of any radical feminist element in the protest. The demands all essentially revolve around questions of control – the students want a say in how the school is run, while the administration is unwilling to cede any power.

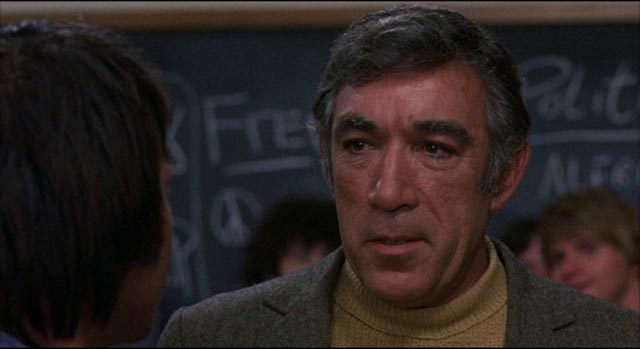

When the dean resigns, the board accedes to the first demand and talks a popular but reluctant sociology professor, Paco Perez (Anthony Quinn), into temporarily taking over the position in order to negotiate. The students initially believe – based on his writings and teaching – that he’ll be on their side, while the board believes his unconventional image will work to their advantage.

That image, established early in the film, is the first big problem. Paco, as one board member says, likes his students … a lot. I’m not sure how questionable his behaviour might have been perceived at the time, but today he looks like a creepy predator. The film seems to expect us to see his sexual exploitation of his students as a signifier of youthful vigour. An inordinate amount of time is spent on his domestic situation with Rhoda (Ann-Margret) – whom we’re assured is a graduate student, as if that takes the curse off. We never see her doing student things, just hanging around his house in skimpy outfits, cooking his meals, cleaning … being a subservient sex object less than half his age.

As negotiations proceed, Paco gets the board to accept the initial nine demands, but the final three which would essentially hand over running of the school to the students are unacceptable. Paco can’t shift either side, losing everyone’s confidence … when revolution is demanded, reason and compromise simply stand in the way. The students’ intransigence leads to more extreme behaviour, the threatened destruction of the administration’s expensive computer, and Paco finally admits defeat and calls in the police.

The film’s most absurd moment comes just before the assault on the occupied building, when Paco says to the police chief (Graham Jarvis) “Remember, no violence.” Tear gas is fired through the windows, chaos ensues, and the cops club the students into bloody submission. In an odd attempt to find some kind of liberal redemption, the final sequence has the school paying bail for the arrested students … but for Paco it’s too late; Rhoda has had her social conscience awoken and their relationship is over.

Paco didn’t want to resort to violence but everyone else’s refusal to compromise left him no choice. When pushed to the edge, the liberal must come down on the side of order against chaos. The world is unfair, because it forces him to violate his own principles. Needless to say, this is an unsatisfactory conclusion, coming as it did just four months after National Guard troops opened fire randomly on students at Kent State, killing four and wounding nine more. In the real world, the forces of “order” had proved unreasonably lethal (many of those who were shot hadn’t even been taking part in the protests against Nixon’s illegal bombing of Cambodia). In the film’s world, it’s an affront to liberal reason that the two sides can’t just learn to get along.

R.P.M. is an interesting artifact, and apart from the queasy sexual situation, not unentertaining. Perhaps recognizing his own limitations, Kramer retreated from such direct address to the current political situation. His next film was Bless the Beasts and Children (1971), about a group of misfit kids who try to save some wild animals from bloodthirsty hunters; then there was Oklahoma Crude (1973), a period comedy about rugged individualists facing down greedy capitalists; The Domino Principle (1977), a muddled and extremely dull paranoid thriller; and finally The Runner Stumbles (1979), a dull squib with Dick Van Dyke as a priest discreetly in love with a young nun. It’s almost as if taking on the revolution at the end of the ’60s had broken Kramer.

*

All three movies get excellent presentations from Indicator, with various informative extras.

Comments