Boxed In

I’ve mentioned before that I love box sets. While every movie needs to stand on its own merits, there’s no denying that almost any movie when seen in a larger context gains something – whether from being seen as part of a filmmaker’s larger body of work or as something which draws on traditions of genre or style, the individual film takes on meanings (and pleasures) not necessarily intrinsic to itself. Here, some notes on three sets – two recent releases, the third seven years old now, though I’ve only just got to it.

William Castle at Columbia Vol. 2 (1962-63)

Indicator’s second box set devoted to William Castle follows chronologically from the first. Because of the focus on his return to Columbia in 1959, that initial set skipped Castle’s first two independent horror productions (Macabre [1958] and House on Haunted Hill [1959]) and included the four movies he made between 1959 and 1961. The second set picks up in 1962 and runs to 1964. Personally, I found the follow-up a bit of a slog to get through. This was the period during which Castle was trying to escape the trap he’d created for himself with his his famous (notorious) promotional gimmicks. Although his movies tended be profitable, he hankered to be taken more seriously as a filmmaker.

This was one of the reasons he strove to branch out of horror and try other genres. While the first set included three of his best movies and one of his weaker efforts, the second set reverses this by including just one of his best along side three of his less (in my opinion) effective movies. The weaker movie in the first set aimed more for strained comedy than horror; the second set unfortunately leans heavily on comedy, a genre Castle was not particularly adept at.

Zotz! (1962), adapted by Ray Russell from a satirical novel by Walter Karig, tries hard to emulate Disney’s family-friendly fantasies like The Absent-Minded Professor (1961). Here, the protagonist is professor of ancient languages Jonathan Jones, who comes into possession of an ancient coin, the inscription on which when translated (and supplemented by blood from a conveniently cut finger) gives him powers of life and death – a pointed finger inflicts crippling pain, speaking the word “Zotz” slows time, and pointing and saying the word kills. When Jones realizes what he’s got, he tries to provide his services to the Pentagon, but initially fails to persuade the military that he isn’t simply delusional.

He uses the coin to get the better of his rival for a departmental promotion at the college, and then finds himself in the hands of Russian agents who believe he has a new secret weapon. His niece and potential girlfriend are kidnapped to force him to cooperate, but he eventually manages to use the coin to defeat the Russians … and finally get recognition from the military, and that departmental promotion.

Zotz! is full of strained and protracted slapstick business, which may have been amusing for kids in the audience, but is pitched a level below classic Three Stooges routines. The cast is quite good – Julia Meade as Professor Fenster, the potential love interest, a self-possessed professional whom we first meet when Jones’s power inadvertently blows all her clothes off; Zeme North as Jones’s niece; Jim Backus as Jones’s rival Horatio Kellgore; Cecil Kellaway as the amiable department head and the inimitable Margaret Dumont as his wife, seemingly unchanged at 80 from her days as Groucho Marx’s foil.

Apart from Castle’s rather leaden sense of comedy, the biggest problem is Tom Poston as Jones. As his career indicates, he was better suited to goofy supporting characters in television sit-coms than leading roles on the big screen. His performance strains for a kind of charming naivety, but progressively slides from dumb to stupid, with Castle giving him way too much room for mugging.

In trying to broaden his audience from teenage drive-in crowds, Castle actually reduces the appeal to undemanding kids.

In his next movie, Castle continued to aim for that Disney appeal. 13 Frightened Girls (1963) is essentially Nancy Drew dropped into a Cold War thriller and could easily have starred Hayley Mills. Scriptwriter Robert Dillon was apparently more comfortable with adult material, going on to write X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes for Roger Corman, Prime Cut for Michael Ritchie and French Connection II for John Frankenheimer. The point of view here is determinedly adolescent, but there are some fairly graphic murders and even a bit of sexual peril for the 16-year-old heroine, Candy Hull (Kathy Dunn). One of thirteen diplomats’ daughters attending an exclusive school in Switzerland, Kathy returns to the U.S. embassy in London for vacation and hangs out with her schoolmates whose dads are stationed at various other embassies. The most radical aspect of the mocie is that among her friends are girls from behind the Iron Curtain and China. The political divisions in the world are seen almost as a stupid aberration of adults.

Given her “contacts”, Candy gains bits and pieces of information which she passes on anonymously to State Department employee Wally Sanders (Murray Hamilton), taking on a secret persona as agent Kitten. Wally doesn’t have a clue who’s leaving notes in his office, but his boss – Candy’s dad attache John Hull (Hugh Marlowe) – thinks he’s just being cagey to protect the agent’s identity. The more Candy digs for information, the greater the danger she faces – including an uncomfortable encounter with an East German agent whom she’s trying to seduce; he drugs her and plans to toss her off his balcony, though she manages to get the better of him and he falls to his death.

The movie breezes over the fact that she’s committed murder – well, killed in self-defence, although she put herself at risk in the first place – and she remains insufferably perky as she gets deeper into danger. Her identity compromised, she’s targeted by Chinese assassins (and a double agent) controlled by attache Kang (Khigh Dhiegh, fresh from brainwashing Laurence Harvey in The Manchurian Candidate), but her schoolfriends come to her rescue.

The mix of deadly espionage with teenage girl issues (romantic rivalries, quarrels with close friends) does give the movie an odd, distinctive tone, though Castle’s awkwardness with comedy produces heaviness where it should be light and breezy. This is most pronounced in the scene when Candy returns to London and immediately visits Wally in his office. She has a crush on the older man and proceeds to attempt to seduce him, pinning him back in his chair and all but oozing over him. Her aggression and his ineffectual resistance give the scene an uncomfortable pedophile fantasy ambience.

Castle worked with writer Robert Dillon again on his next movie later that same year, a remake of The Old Dark House, originally adapted from J.B. Priestley’s 1928 novel Benighted by James Whale in 1932. Although Whale’s masterpiece is blackly comic, Castle’s version aims for lighter comedy, more along the lines of the Bob Hope version of The Cat and the Canary (Elliott Nugent, 1939). Made as a co-production with Hammer Films, the movie benefits from production design by Bernard Robinson and photography by Arthur Grant which give it images a satisfying density … and it also benefits from an excellent English cast which includes Robert Morley, Peter Bull, Joyce Grenfell, Mervyn Johns, Fenella Fielding and Nanette Scott.

But once again Castle cast Tom Poston as his lead Tom Penderel, an unwitting American who finds himself stuck in the decaying mansion of the eccentric Femm family. Trapped together in the old house, none of them can leave without forfeiting their share of an inheritance from their pirate ancestor. Now, on the weekend that Tom comes to stay, someone is bumping off members of the family, reducing the number in line for the money. Poston comes across as a lightweight among the English pros, who all revel in their characters’ eccentricities.

It struck me while watching that Poston bears an uncanny resemblance to a young William Castle, exhibiting a similar slightly self-mocking manner. As in Zotz!, Poston’s mugging drags the movie in the direction of TV sit-com despite the energy of the rest of the cast. The funniest thing about The Old Dark House is the account in the accompanying booklet of its problems with the British Board of Film Censors; it took Hammer a couple of years to attain an A certificate, allowing kids to see it when accompanied by an adult. It seems ridiculous now that BBFC insisted that the comedic corpses warranted a restrictive X certificate.

The following year Castle returned to form with what turned out to be one of his best horror films. Having modelled 1961’s Homicidal on Psycho, which had been adapted from a novel by Robert Bloch, Castle recruited Bloch to write an original psycho thriller, which itself drew on the recent success of Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). Castle managed to convince the notoriously difficult Joan Crawford to star in Strait-Jacket (1964). In his autobiography, Castle recounted his excitement about the opportunity to work with a “real star” (which seems a little hard on Vincent Price, who had helped put Castle on the map just a few years earlier).

Strait-Jacket helped to consolidate Crawford’s late career shift as a horror icon. At age 60, she embraced with apparent ferocity Hollywood’s view that there was something inherently monstrous about aging women. The fact that she continued to express her sexuality – as she would again the next year in Castle’s I Saw What You Did and a couple of years later in Jim O’Connolly’s Berserk (1967) – added, in the film’s own terms, to the monstrosity. In a movie featuring relatively graphic beheadings by axe, perhaps the scariest (certainly most uncomfortable) scene is the one in which Joan, as former axe-murderer Lucy Harbin starts hitting on her daughter’s fiance.

After a brief prologue in which Lucy returns from a trip early to find her husband (Lee Majors in his first screen role) in bed with another woman and chops them both up with an axe, in front of her young daughter, Lucy is released from the asylum where she’s been confined for twenty years. Nervous and insecure, she arrives at her brother’s remote farm and begins to re-establish a relationship with now-grown daughter Carol (Diane Baker), who was adopted by Uncle Bill (Leif Erickson) and Aunt Emily (Rochelle Hudson). Lucy isn’t ready to meet people and it’s her overwrought attempt to seem “normal” – by behaving as if the past twenty years had never happened – that leads to the very awkward scene with Carol’s boyfriend Michael (John Anthony Hayes).

Lucy’s grip on reality is tenuous and a string of mysterious events make it appear that her long spell in the asylum has not “cured” her – she wakes at night to find the heads of her husband and his girlfriend on the pillow beside her, a bloody axe lying on the bed. She hysterically runs from the room and when everyone finally goes to look, there’s nothing there. Things escalate when her doctor shows up to see how she’s doing and gets chopped in the barn; then creepy farmhand Leo (George Kennedy) loses his head … with Carol showing her concern by concealing what seem to be Lucy’s new crimes.

Joan gets to pull out all the stops when she’s invited to dinner by Michael’s parents. They’re a snooty, class conscious couple who are appalled at the idea of their son marrying a nobody like Carol, let alone the daughter of a murderer. Lucy unloads on them with fury at their condescension towards Carol. This argument precipitates a murderous climax which works as a kind of mirror image of Psycho’s conclusion.

Strait-Jacket more than borders on camp, thanks to Crawford going full-throttle despite the unflattering nature of her role. The rest of the cast hold their own, all knowing that they’re there to support the star, with Baker quite fearless in matching Crawford’s intensity. Strait-Jacket, like Homicidal, may be derivative, but it’s one of the better post-Psycho horror thrillers, Crawford making up for Castle’s typical workmanlike direction by taking control of the movie. She gives herself totally even though she can’t have been unaware that it was transforming her larger-than-life image into a grotesque caricature of her Hollywood glamour.

As with the first Castle box set, Indicator has supplemented strong transfers with copious extras. All four features get a commentary track, there are three versions of The Old Dark House (U.S. black-and-white, shortened U.K. theatrical, and full-length colour), multiple alternate title sequences for 13 Frightened Girls each focusing on a different nationality, plus numerous featurettes on each film and Indicator’s usual substantial booklets.

*

Hemisphere Horrors (Various, 1964-71)

Although William Castle’s movies were usually money-makers, he never got much critical respect. Nonetheless, those movies are recognizably part of the Hollywood mainstream – he was never a transgressive outsider like Herschell Gordon Lewis of Andy Milligan. The key movies in Severin’s Hemisphere Horrors box set, however, seem to have come from another planet entirely. Production and distribution company Hemisphere Pictures was a classic low rent exploitation outfit whose success rested to a large degree on its acquisitions from the Philippines, particularly the Blood Island series of quirky horrors made by Gerardo De Leon and Eddie Romero.

Those four movies were previously released as a set by Severin; the new set feels less coherent and serves as a kind of footnote or supplement. The best movies in the box are a pair of Gothic vampire tales directed by De Leon. Like the Japanese Bloodthirsty Trilogy, these draw on the European tradition, but run those familiar tropes through an exotic filter which transforms familiar settings and characters in strange ways.

In The Blood Drinkers (aka Kulay Dugo Ang Gabi, 1964), we get fog-shrouded graveyards and an old church, a mansion whose inhabitants live under a curse, woods where peasants are preyed on by members of a vampire cult … but none of this has the sombre Gothic tone of a Hammer movie. The story revolves around lead vampire Dr. Marco (Ronald Remy), a cape-wearing, lovelorn bloodsucker whose beloved Katrina (Amalia Fuentes) is dying. His remedy is to find Katrina’s identical twin sister Charito (also Fuentes) and ransack her body for blood and organs to rejuvenate Katrina.

Charito was sent away as a child and knows nothing of her family history, while her birth mother who is involved with Marco, but not a vampire herself, is torn between sacrificing one daughter to save the other. It falls to Charito’s friend Victor (Eddie Fernandez) to fight the cult and save her.

The Blood Drinkers is steeped in foggy atmosphere and an eccentric visual style, partly the result of a money-saving decision to shoot a lot of night scenes in black-and-white, tinting them in post-production – either red for those featuring vampire activity and blue for calmer scenes. Someone actually comments on the English soundtrack about the night turning red, a sure sign of the vampires’ presence … I wonder whether this was added to explain the visual eccentricity to drive-in audiences, or whether it’s actually in the original Tagalog dialogue.

The colour scenes are reminiscent of Mario Bava’s work, using filters to heighten contrasting hues. That stylization is a bit more restrained in the set’s best movie, De Leon’s Curse of the Vampires (1966). The narrative is more coherent this time. There is a curse hanging over the Escudero family, and brother Eduardo (Eddie Garcia) and sister Lenore (Amalia Fuentes again) find out about it when they return home to find their father (Johnny Monteiro) sick and irrational. He’s changed his will and insists that the family home must be burned to the ground when he dies. Naturally, this bothers the kids who anticipate an inheritance.

Strange cries in the night eventually lead to the shocking discovery that their mother (Mary Walter) is a vampire kept chained in the basement (and regularly whipped by dad). Eduardo foolishly gets too close and mom bites him; he takes to being a vampire with enthusiasm, preying on the locals and eventually targeting Lenore herself. It gets twisted and tragic, with a lot of intra-family mayhem. De Leon manages to imbue it with some genuine emotion, not least through a surprisingly moving performance from Walter as the mother who is compelled by her condition to do things which obviously torment her.

Both movies are thick with Catholic iconography and religious dread in ways which contrast with the rote religious elements of Western vampire movies; they were made in a place where the religion was still very much alive.

The cultural nuances of the Filipino movies is nowhere in sight in Brain of Blood (1971), an attempt by Hemisphere to cash in on its most famous properties for even less money than it took to produce movies in the Philippines. Cooked up by Hemisphere’s marketing genius Sam Sherman and directed by Al Adamson, who seldom rose to the level of Herschell Gordon Lewis, Brain of Blood is tedious nonsense. Amir (Reed Hadley), beloved leader of Kalid, is dying and there’s only one way to prevent the country from falling into chaos – he must be flown in secret to the United States where mad doctor Trenton (Kent Taylor) plans to perform an illegal brain transplant, rehousing Amir in a younger, stranger body which will be modified cosmetically to hide the switch.

In classic mad doctor fashion, Trenton hasn’t obtained the new body before the arrival of Amir’s brain – which can survive only a couple of hours. So off goes badly scarred, mentally deficient, mute assistant Gor (John Bloom) to find one. In equally classic mad doctor’s assistant mode, Gor drops the intended body off a roof. Trenton, very annoyed and with no time to spare, decides to pop Amir’s brain into Gor’s body, despite the very obvious lack of resemblance. He doesn’t really care about Kalid’s political problems; he’s just interested in the scientific aspects of the procedure.

Naturally, Amir is appalled when he gets a look at his new self and he loses it, going on a murderous rampage – and finding his mind somehow getting contaminated by an inexplicable residue of Gor’s personality.

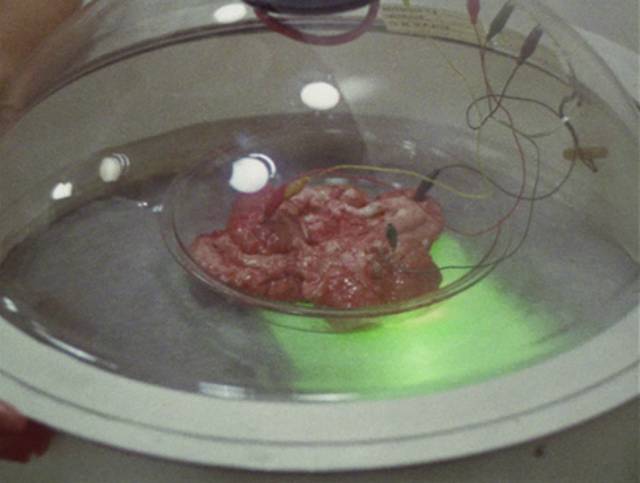

All of this is really cheap and clumsy, with the operation itself drawn out to interminable length with close-ups of scalpel slicing through skin and a calf’s brain being roughly handled by the doc. Although Sherman claimed that the intention was to make it look as if the movie was shot in the Philippines, it’s obvious that the nondescript locations were somewhere around Los Angeles (actually Topanga Canyon).

Apart from the rather graphic medical procedure, the movie’s only real point of interest is the casting of ’50s genre icon Grant Williams (The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Monolith Monsters, not to mention Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind) as hero Bob and Angelo Rossitto as diminutive lab assistant (and friend of Gor) Dorro. Rossitto’s career spanned a remarkable sixty years and almost a hundred credits, including Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and George Miller’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), with an appearance in Orson Welles’ posthumously completed The Other Side of the Wind (2018).

These first three movies in the set all get commentaries and featurettes. The final two share a single disk with no extras. Harold Reinl’s The Torture Chamber of Doctor Sadism (1967) is a German Gothic very loosely based on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum (which was the original, less sensational, German title), with Roger (Lee Barker) trying to uncover the mystery of his own past, hooking up with Milian (Karin Dor) to travel to a remote castle where Count Regula (Christopher Lee) was executed for terrible crimes thirty years earlier. The Count is struggling to come back from the dead and gain eternal life, a plan which involves draining the blood of local virgins.

The movie draws on the traditions of the Italian Gothic movies of Mario Bava, Antonio Margheriti and the like, and Reinl does come up with a few striking images – particularly a mountain road through woods where numerous corpses hang from the trees – but it feels much pulpier than Bava’s elegant period films. Reinl was always better with his krimi thrillers.

The final movie in the set is a regional oddity shot in Dallas in 1966 by Harold Hoffman, who wrote Larry Buchanan’s The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald (1964). The Black Cat features Poe’s idea of a cat bricked up in a cellar, whose cries give away the location of a murder victim, but it takes a rambling route to get there. On their first anniversary, doting wife Diana (Robyn Baker) gives her husband Lou (Robert Frost) a black cat. Lou, a would-be writer, becomes inordinately attached to the animal, transferring his affections to it as his alcoholism gets worse, causing problems in the marriage.

In a drunken rage, believing the cat is a reincarnation of his hated father, he digs its eye out with a knife, takes it up on the roof, and hangs it with electrical wire. As the wire sparks, it sets fire to the house. Things get worse from there; turns out that dad never insured the house, so Lou and Diana are now homeless. Lou attacks the attorney who gives him the news and ends up in a sanitarium for his alcoholism. When he’s released, Diana takes him back for some reason, but he continues to drink, finds a one-eyed cat, goes go a go-go club where he hallucinates all the band members having eye patches… Back home, he again tries to rid himself of the infernal cat, but things get even worse, leading finally to that Poe climax.

The black-and-white movie has an authentically grungy atmosphere, and Frost is surprisingly good as the unpleasant alcoholic. The Black Cat belongs to that interesting strain of low-budget regional horror which flourished in the ’60s and ’70s, and like many of those movies it was made by people who did little else despite the talent they displayed.

*

Trilogy of Life (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1971-74)

While it would difficult to argue for the Castle and Hemisphere movies as some kind of art, that’s not the case with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life, although he was attacked by various critics and censors when these films were released in the early 1970s. A Catholic Marxist homosexual poet, novelist and essayist, he had turned to film in the ’50s, first as a writer (he worked on the scripts for Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria and La Dolce Vita), then as a writer-director beginning with Accatone in 1961. His early work drew on the tradition of Neorealism with stories of street life viewed through the lenses of leftist politics and poetry: Accatone and Mamma Roma (1962) both deal with the social and economic dimensions of prostitution. He blended his politics and religious influences in his segment of the portmanteau film RoGoPaG (1963), in which poor villagers are exploited by a film company in a production of the life of Christ, and The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), which remains the most faithful adaptation from the Bible, despite presenting Christ as a political revolutionary rather than a messianic prophet. Towards the end of the ’60s, Pasolini was becoming frustrated with the messy politics of the time and the difficulty of commenting on them without becoming implicated in their failings.

And so in 1971 he made a deliberate choice to turn away from the present and embarked on a three-year project to adapt a trio of pre-modern texts, the first two of which were foundational literary and cultural works in their respective nations, while the third was somewhat more problematic, having less clearly defined origins and a history of appropriation by Europeans of elements of another culture, now seen as stained with an imposed exoticism which distorts whatever the original sources may have been. What all three works shared were a depiction of pre-capitalist social relations and a more open acceptance of physicality and sex unencumbered by modern moral constrictions.

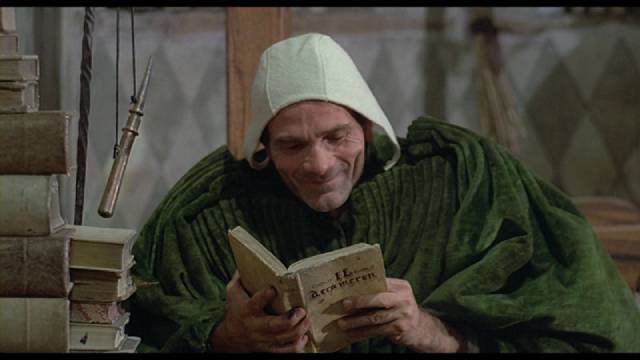

Beginning with Boccaccio’s Decameron, written in the mid-14th Century, and continuing with Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written a few decades later, and ending with The Arabian Nights, which unlike the other two had no specific author – it was a collection of folktales compiled over centuries, possibly dating back to the 10th Century, and first translated into a European language (French) in the early 18th Century – Pasolini adopted a style reminiscent of Medieval pageants, but discarded stories dealing with kings, queens and nobles to focus on the lives of people at the lower end of the social scale.

Like their sources, the films are rude, ribald and full of the sheer physicality of existence – eating, shitting and pissing, and most importantly and pervasively fucking. While the stories taken from Boccaccio and Chaucer are to a degree overshadowed by Christian morality, something which everyone needs a certain degree of subterfuge to evade in order to enjoy sexual pleasures, The Arabian Nights, freed from the Church and largely avoiding Islam altogether, presents an idealized world of unselfconscious polymorphous sexual pleasure. Homosexuality is presented in these Eastern fables as unremarkable, where in Canterbury Tales it is a crime, but one surrounded by hypocrisy. At one point Church authorities expose two different men engaged in forbidden acts; the wealthy man pays a bribe and goes free while the poor man is burned at the stake.

With the Trilogy Pasolini broke new ground in what could be shown on screen; the films are full to the brim with casually displayed male and female nudity and various forms of sexual coupling, often depicted with more humour than romantic sentiment – in these worlds, sex is one more natural function, a form of pleasure to be indulged without guilt.

Critics on the left accused Pasolini of turning his back on the urgent imperatives of contemporary politics and indulging in a reactionary fantasy of some mythical, ahistorical past, while the right attacked him as a pornographer. The naturalism of Pasolini’s sexual displays tends to work against the attractions of pornography, which derives much of its power from the very fact that it’s displaying something forbidden and therefore unwholesome. Pasolini’s pre-modern fables bypass that frisson of guilt, their exuberance giving the films an air of innocence which disarms all but the most rigid moral criticisms.

However, despite his creative intentions, Pasolini nonetheless made these films inside a modern culture weighed down by various official moral dictates and powered by capitalism … and so the door he opened was quickly exploited by others without his artistic bona fides; hard on the release of his films, the market was flooded with knock-offs which used his period settings as an excuse for the presentation of crass pornographic movies of the kind he had so assiduously tried to avoid. Seeing his work appropriated so quickly and aggressively by the market, Pasolini renounced the Trilogy the year after it’s completion, and embarked on his final film, the grimly anti-pornographic Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975).

Criterion’s three-disk Trilogy of Life set surrounds the colourful restorations with a hefty collection of extras which cover the origins of the project, material cut from the final versions, appreciation of the films and their place in Pasolini’s body of work. There’s some print damage on The Canterbury Tales, but it’s not too distracting, and Criterion have included the English-language track as an option on that film; this is appreciated because it gives us not only the sound of Chaucer but the actual voices of many of the actors. Apparently Pasolini went to great lengths to give the Italian version a rough vernacular track appropriate to period, but that effort would be lost on an English-speaking viewer. The set is an impressive release (from 2012), which at this distance effectively counters Pasolini’s own renunciation – the Trilogy is his most purely pleasurable cinematic work.

Comments