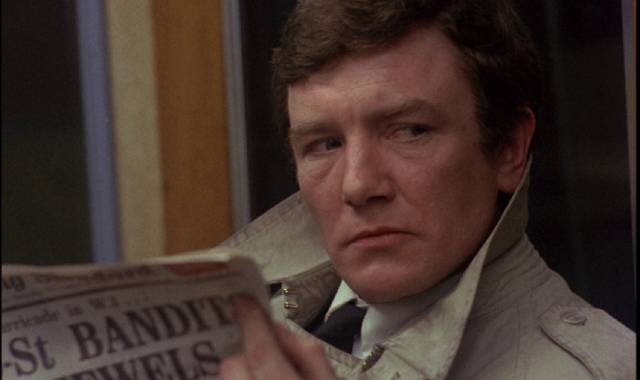

The enigmatic Albert Finney

Acting has a strange kind of alchemy. Actor and role are mysteriously intertwined with each other. How is it that we can immerse ourselves in the narrative world of a movie, feeling complex emotional engagement with the lives of the characters, while simultaneously being fully aware of the people playing those characters? Even as I experience this, I honestly don’t know what’s going on.

Beyond this global process, there are equally strange individual aberrations, peculiar chemical reactions between actor and audience member. Why do we develop an affection for one performer and an antipathy for another? For some odd reason, I often find myself at odds with judgements about the “greatest actor of his or her generation”. Laurence Olivier, Meryl Streep, Daniel Day Lewis … to me they all seem distanced by their technique; rather than inhabiting a character, I always feel that I’m watching them constructing some kind of monumental edifice. The edifice may appear impressive, but for me it’s seldom a character I can relate to emotionally.

I react to Albert Finney the same way. He always seems to be wearing a character like a suit of armour, concealing something essential rather than revealing it. Finney’s hard shell puts me off, even in films which I can appreciate on most other levels. Seeing him in something like Peter Yates’ The Dresser (1983) or John Huston’s Under the Volcano (1984), I imagine what the movie might be like without such thickly sliced ham at its centre, but at least the ham is more or less in tune with the film’s intentions. In other cases, he can disrupt and even destroy an otherwise fine film with his bluster.

Stanley Donen’s Two for the Road (1967), for instance, has a carefully, even delicately constructed script by Frederic Raphael which conveys the emotional changes which occur in a relationship over time, the progress from romantic illusion to melancholy disillusion. Everything about the production is quite wonderful, from the script, to Donen’s skillful visual shifts back and forth in time, to a typically charming performance from Audrey Hepburn … but the whole movie is ruined by Finney, who plays the part of the husband as an obnoxious emotional bully even in the scenes depicting the beginning of the relationship. It’s impossible to understand Hepburn’s initial attraction to him, and he provides no space for the emotional evolution of the relationship – which is the whole point of the film – to occur. He literally kills a movie which in every respect other than his performance is essentially flawless.

Which is a very long way of arriving at my ambivalence about two interesting movies from fairly early in Finney’s screen career: the self-directed Charlie Bubbles (1968) and Stephen Frears’ feature directorial debut Gumshoe (1971).

*

Gumshoe (Stephen Frears, 1971)

After one dramatic short, several documentaries and some episodic television, Stephen Frears made his feature debut with a very tricky project written by Neville Smith (who also plays the protagonist’s petty criminal friend Arthur, and a few years later would play the screenwriter in Maurice Hatton’s Long Shot [1977]). Gumshoe is a tonally complicated movie which blends a pastiche of classic detective noir with comedy and a rather downbeat depiction of Britain’s post-colonial politics and regional and class divides at the end of the ’60s.

Finney plays Eddie Ginley, a small-time club comic in Liverpool who feels that his life is slipping away into meaninglessness. The woman he loved (Billie Whitelaw) married his more successful businessman brother (Frank Finlay), and his career is going nowhere – he gets to tell a few jokes, but his actual job is calling bingo. So as a birthday present to himself, he puts an ad in the local paper offering his services as a detective. He puts on a trench coat and fedora and talks tough like a character out of Hammett or Chandler … that is, Finney is playing a character (Eddie) who puts on a mask and himself plays a character, or rather a caricature. To counter his own sense of disappointment, Eddie has decided to turn his life into some kind of romantic fantasy. Finney plays the part with tough-guy bluster, while not quite concealing Eddie’s underlying sense of disappointment.

Eddie gets a phone call summoning him to a hotel room where a fat man (George Silver, referencing Sydney Greenstreet’s Kasper Gutman in The Maltese Falcon) tells him to take the envelope off the dresser. Eddie thinks it’s a birthday gag being perpetrated by his friends, but inside the envelope is £1000, a photo of a woman, and a gun. It appears that he’s been hired to murder someone he knows nothing about. As Eddie gradually gets drawn into an increasingly dark story, dogged by the real hit man (Fulton Mackay), he uncovers some unsavoury facts about his brother, witnesses a pathetic murder in a seedy hotel room, and exposes a plot involving gun-running, kidnapping and political conflicts between the White government of Rhodesia and the African Nationalists who were fighting it.

The initial comedic tone of the film and the dark and violent reality it ultimately exposes are held together by the character of Eddie; in looking for something more exciting and meaningful in his life he discovers grim truths which are uncomfortably close to home. Wanting at first to be funny, he ends up sad and disillusioned. I’m not sure that Finney brings off this difficult trajectory, because so much of his performance consists of a deliberate masquerade – Eddie the detective is patched together from old movie references, and he leads Eddie the comic somewhere he didn’t expect the fantasy role-playing to take him. But the original Eddie is largely submerged under the play acting, so the emotional impact of what he experiences and learns remains uncertain.

Gumshoe was made the same year as Mike Hodges’ Get Carter and there are some similarities – the bleak Northern settings, the investigation which exposes the rot beneath the surface of British society – but while Michael Caine immersed himself completely in the character of the thuggish Carter, Finney – partly due to the conception of the role – never escapes the impression of someone merely play acting, putting on the character of Eddie rather than actually becoming him.

Indicator’s Blu-ray has an excellent, film-like image and is packed with interviews from director Frears and writer Smith, producer Michael Medwin, editor Charles Reese, production designer Michael Seymour and supporting actor Tom Kempinski. There’s also Frears’ 32-minute first film, The Burning (1968), about a patrician white woman in South Africa who is oblivious of the rising tide of African Nationalist violence around her.

*

Charlie Bubbles (Albert Finney, 1968)

Charlie Bubbles (1968) is a more interesting movie in a number of ways, not least in that it was the only film Finney ever directed himself. Obviously a more personal project, it is nonetheless somewhat opaque, with director-star again concealing as much as he reveals. The script by Shelagh Delaney, her first original work for the screen (she had adapted her play A Taste of Honey in 1961 for director Tony Richardson), drew on experiences she shared with Finney. Both of them had been born in Salford, Lancashire, and had become successful in London – a fact which alienated them to a degree from their roots.

Charlie is a best-selling author who deals with his celebrity by withdrawing as much as he can from it. In the first scene, he’s having dinner at a restaurant with his accountant and manager who are trying to work out how best to protect his earnings from the taxman. Charlie seems utterly bored by it all, and after a drunken binge with his boozy friend Smokey Pickles (Colin Welland), he heads North with his assistant Eliza (Liza Minnelli in her big-screen debut) to visit his ex-wife Lottie (Billie Whitelaw again) and neglected son Jack (Timothy Garland). Along the way he meets various people who react to his celebrity, but seem largely unaware of his unresponsiveness and alienation.

His relationship with Lottie is prickly and he has a hard time relating to Jack – eventually losing him at a football match. After a panicked search, he heads back to Lottie’s house dreading her reaction to Jack’s disappearance … but the boy is already home, having taken the train by himself, and Lottie is disgusted by Charlie’s irresponsibility.

Not much happens in the film other than small incidents which serve to confirm Charlie’s disconnection from his past, and also from his present successful life. He doesn’t really know who he is and is harshly judged by those who have been closest to him and idolized by those who only know him through his success. The characters’ names indicate that the film is a comedy, but its tone is downbeat and melancholy – even the fumbled sexual encounter between Charlie and Eliza in a motel room is joyless and embarrassing. Charlie seems to embody the emotional armour which Finney so often seemed to wrap himself in as a performer. The seemingly whimsical ending – Charlie leaves Lottie’s house, crosses a field and climbs aboard a hot air balloon, sailing off into the empty sky – suggests a desire on Finney’s part to simply walk away from his own rising fame and the public image of him as the face of the British New Wave.

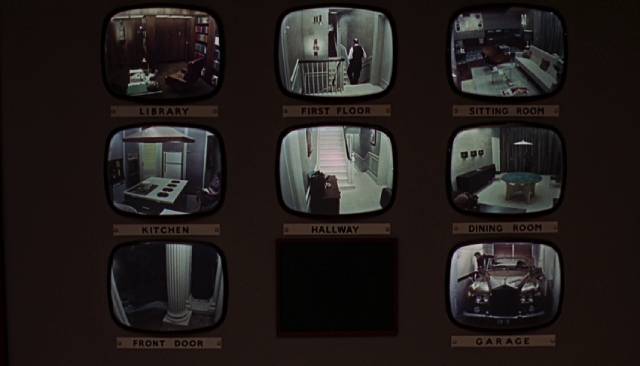

It seems odd that he didn’t direct again, but stuck with the acting career about which he himself was ambivalent. As it is, he displays genuine talent behind the camera, both in his staging and visual sense (the film was shot by Peter Suschitzky, so Finney had strong support there) and in his work with an excellent cast; the performances are uniformly fine. There’s a striking sequence early in the film in which Charlie, in his home office, observes the activities going on in the house via a bank of closed-circuit TV screens – it has an almost science fictional feel, Charlie as Big Brother tracking the lives of servants and friends, but also drives home his detachment from the lives around him.

The image on Indicator’s Blu-ray has a slightly grungy quality, echoing the kitchen-sink realism of ’60s British cinema. There’s a commentary by film historians Thirza Wakefield and Melanie Williams, and a collection of interviews with various cast and crew members.

*

Both films are interesting and are given fine presentations by the always reliable Indicator, but I can’t say they’ve altered my feelings about Albert Finney as an actor. He remains somewhat distant and enigmatic.

Comments