“Folk Horror”

“Folk horror” is a vaguely defined category, first named by director Piers Haggard to describe his film Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). Like the equally difficult to define film noir, folk horror is the kind of thing that you know when you see it, even if you can’t quite pin it down. Broadly, it encompasses stories in which pre-modern beliefs linger on and infiltrate the world whose rationality we take for granted. Ghosts, spirits, religious cults and magic undermine material certainty in films as diverse as Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015) and Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019). But it can also include such things as fairy and folk tales which take place in a less rational narrative space … traditional Japanese ghost stories like Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968), Nietzchka Keene’s Icelandic fable The Juniper Tree (1990), Neil Jordan’s fairytale The Company of Wolves (1984).

There’s a strong British tradition which can be assigned to folk horror, drawing on a long history of mysticism connected to nature. Going back to the Druids and beyond, the land itself has been seen as imbued with living energy, access to which may bring either power or destruction to those who live with it. This is the core of the Round Table, of Arthur and Merlin and the Knights of the Grail; it also runs through the long tradition of the English ghost story – from Shakespeare to the Gothic fantasists, through the Victorians to M.R. James – a literary tradition embraced by the movies and television: Jacques Tourneur’s James adaptation Night of the Demon (1957), the BBC’s popular Ghost Story for Christmas series and one-off dramas like James MacTaggart’s Robin Redbreast (1970), Alan Clarke’s Penda’s Fen (1970), Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (1974) and Murrain (1975). Even Michael Powell’s A Canterbury Tale (1944) and I Know Where I’m Going! (1945) are infused with this mysticism. More recently, Ben Wheatley produced a masterpiece of the genre in A Field in England (2013).

Britain in the 1960s, like most Western countries, underwent a great deal of social upheaval. Dissatisfaction with the status quo which emerged during the recovery from World War Two took many forms – the rise of violent criminal gangs, rejection of authority by the postwar generation which manifested in Teddy Boys and the Mods and Rockers, who fought one another and the police with nihilistic enthusiasm. It was also manifest in a renewed interest in various forms of mysticism, from the embrace of Eastern gurus by pop stars and hippies, to a revival of the occultism of figures like Madame Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley, the Golden Dawn and other esoteric societies.

This emerged in popular culture as a string of movies dealing with witchcraft, the Devil, and pre-Christian religions. Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968) is considered one of the first folk horror movies, although it contains nothing fantastic or magical. The witchcraft which plagues southern England in the 1600s is an invention rooted in superstition, a justification for imposing violent control over a society in upheaval. The monster here is Matthew Hopkins, a vile opportunist who exploits chaos for his own financial and psychological gratification. The same attitude shows up in Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil (1970), in which witchcraft and the Devil are inventions of the authorities to disguise their own sexual sadism.

Haggard turned this essentially realist horror on its head with Blood on Satan’s Claw, in which the Devil is quite real and spends his time corrupting the children of a village, stirring up illicit sex and violence. Witchfinder General looks back at a particular historic moment with modern eyes, seeing through local superstition to a psychological explanation; Blood on Satan’s Claw, like Eggers’ The Witch, sees the world through the superstitious beliefs of that time.

*

The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1973)

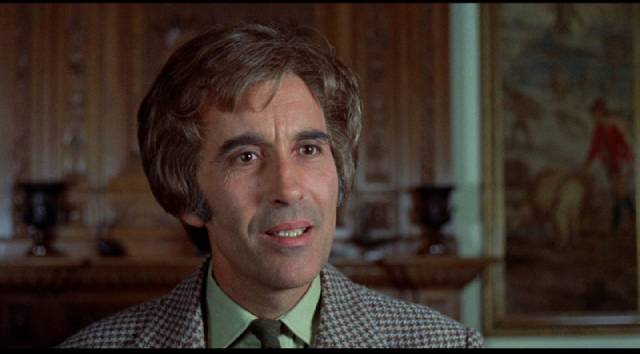

A more complicated balancing act is at work in the key film of the folk horror genre, such as it is. Robin Hardy and Anthony Shaffer’s The Wicker Man (1973) takes as its subject clashes between Paganism and Christianity, reason and superstition, refusing to come down on either side but instead finding horror in the very idea of unshakable belief. Rigidly humourless Protestant policeman Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) flies to the remote private island of Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), famous for its fruits and vegetables grown where the climate should make it impossible. He has come to investigate the reported disappearance of a young girl, a girl whom nobody will admit to knowing.

Appalled by what he sees as the lax morals of the islanders – disbelief in Christianity, open and guilt-free sexuality – Howie becomes rude and aggressive. His own absolute certainty in his rigid and joyless religious beliefs causes him to see the islanders’ unapologetic Paganism, supposedly rooted in ancient Celtic mysticism, as a disgusting affront to all that’s proper. By the time his investigation comes to an end with the revelation that he himself has been the quarry all along, the viewer has lost all sympathy with him, seeing the harmony between the local population and the land as a positive expression of a then-awakening ecological consciousness.

But in the film’s final moments that sympathy collapses. The islanders’ beliefs about their place in the world and their responsibility to nurture the land which sustains them leads them into superstition just as deadly as that of Christians who used to murder old women they believed to be witches. What the terrified Howie cries out in his final moments – that the crop failures are due to poor management and inappropriate plants for this climate and soil – is no doubt scientifically true, but his words are meaningless to people who have immersed themselves so completely in old beliefs. For them, the only solution to their troubles is human sacrifice to the gods of land, sea and sky and the virginal Howie with his strong beliefs makes for the perfect victim.

The joyful singing of the islanders as they dance around Howie, burning alive in the great wicker figure on the hilltop, is as chilling an expression of religious fanaticism as you’ll find on screen. Ultimately, The Wicker Man stands as a critique of all irrational religious belief – despite aspects which may seem appealing in themselves, such beliefs lead inevitably to madness and monstrous behaviour.

*

The White Reindeer (Erik Blomberg, 1952)

While The Wicker Man is shaped by a dialectical argument about conflicting religious beliefs, Erik Blomberg’s The White Reindeer (1952) combines ethnographic documentary with a folk tale from an oral tradition. Not just the feature debut of cinematographer Blomberg, it was the first Finnish horror film, winning an award at Cannes and a Golden Globe in the States. Shot on location in Lapland, the winter landscapes and largely non-professional cast can’t help but remind the viewer of Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922). Blomberg evokes the daily lives of Lapp reindeer herders in visceral detail, the absence of discernible temporal markers giving the film a timeless quality; the inhabitants of this land live lives which appear not to have changed in centuries.

As Blomberg’s camera is attentive to the landscape and the ways in which it shapes the lives of these people – it opens with an exhilarating race of sleds pulled by reindeer – the documentary detail grounds the supernatural events which unfold; the harshness of the setting lends plausibility to the underlying mysticism. The horror of the narrative grows organically from this remote place where the village men disappear for months as they follow the reindeer herds on their migration. The central character is Pirita (Blomberg’s wife Mirjami Kuosmanen, who co-wrote the script with him), a strong independent woman who competes with the village men in that sled race, and then marries Aslak (Kalervo Nissila). Frustrated by their lengthy separations, Pirita consults a shaman and is instructed in how to make herself irresistible to men. It may be that she simply wants to bind Aslak closer to her, but she becomes an object of desire for anyone who comes across her.

The trouble is that as a result of the spell, she becomes a shape-shifter, transforming into a distinctive white reindeer which attracts the attention of hunters, who pursue her to an isolated valley, each meeting a grisly end … in essence the deer is also a vampire, draining them of blood. The film, through its seeming ethnic verisimilitude, naturalizes the fantastical elements of the folk tale, giving emotional power first to Pirita’s strong sexual desire and then to her torment as she becomes aware of the destructive force her desire has unleashed. While the underlying point of the tale may be the danger of trying the break free of the constraints imposed on this woman by her remote community, the film never loses sympathy for Pirita, making her ultimate fate genuinely tragic.

*

Legend of the Witches (Malcolm Leigh, 1970)/

Secret Rites (Derek Ford, 1971)

While not specifically horror, a pair of mondo-inflected documentaries produced in England at the turn of the decade as the Swinging Sixties began their decline into the political and economic anomie which ended in the horrors of Margaret Thatcher’s grim regime do draw on various folk traditions as reinterpreted from a modern perspective. These two movies, released in a dual-format edition by the BFI, use the trappings of documentary in order to exploit material which skirts the limits of what British censors would allow at the end of the 1960s. Both Legend of the Witches and Secret Rites draw on the salacious popular image of witchcraft as revived in the ’50s by Gerald Gardener and his followers; Gardner in turn drew heavily on the work of Margaret Murray in the ’30s (now largely discredited) which proposed that witchcraft in the Middle Ages was rooted in pre-Christian beliefs and practices. This supposed revival gave rise to what is now known as Wicca (which in turn became something of a model for the practices of the islanders in The Wicker Man).

These two movies, while both drawing on and featuring the practices of Alex Sanders, self-proclaimed “King of the Witches”, are ultimately more interested in lengthy displays of nudity than any serious examination of ancient beliefs. Sanders had broken away from Gardnerian practices and rather than guarding the sacred rites flamboyantly publicized himself and his coven in Notting Hill, offering his services as an advisor on movies like J. Lee Thompson’s Eye of the Devil (1966) and giving numerous interviews to the tabloid press.

Malcolm Leigh’s Legend of the Witches (1970) presents itself as a serious documentary, shot in austere black-and-white and beginning with a lengthy account of the mythical origins of witchcraft (concocted by Sanders) before settling into naked romps around a fire in dark woods at midnight. Presenting Paganism as part of the anti-establishment revolution of the ’60s, the film catalogues various rites, taking advantage of Sanders’ willingness to sensationalize by emphasizing the sexual element and going so far as to “document” the casting of a death spell, performance of a Black Mass (which obviously has more to do with inverting Christianity than expressing pre-Christian beliefs), and attempting to peer into the future with a scrying mirror. Through it all, Leigh maintains a sober tone.

The same can’t be said for Derek Ford’s Secret Rites (1971), shot in gaudy colour and largely staged on rather shoddy-looking studio sets with ritual participants dressed in flamboyant robes – when they’re not naked, that is. The movie begins with a debauched romp in a Medieval castle, showing a coven of witches defiling virgins. This sub-Hammer scene ends abruptly as we’re told that this image of witches is completely erroneous. Interestingly, the orgy is presided over by none other than Alex Sanders himself, who will be our guide through the ensuing display of mystic rites.

The thin narrative follows the progress of trendy hairdresser Penny (Penny Beeching, who the previous year had been a regular on TV comedies Up Pompei and The Morecombe & Wise Show) as she goes from Wicca-curious to coven acolyte. She’s first vetted by a coven member, whose job it is to gauge her seriousness. When she finally meets Sanders, she’s told that she faces years of rigorous study – it’s a program designed to weed out those who have only a prurient interest based on the nonsense published by the tabloids. There’s no overt recognition of the irony as we watch Penny undergo a naked initiation in this movie expressly designed to stir the prurient interest of a grindhouse audience.

While Leigh seems to try hard to take all this seriously, Ford is obviously only looking to sell tickets. Both movies are cashing in on a real interest in alternative ways of thinking – Wicca, for instance, as a goddess-centred religion, fed into some strains of feminist thought, and its belief in the close connections between human beings and nature linked it with the nascent ecological movement – but at heart they’re essentially old-fashioned exploitation fantasies, their emphasis on the sexual aspects of witchcraft skirting the horror running through the actual history which saw tens if not hundreds of thousands of witches tortured and killed over a period of three or four centuries.

*

The StudioCanal Vintage Classics Blu-ray of The Wicker Man contains three different cuts. This film’s troubled history is legendary, with Hardy’s original version brutally cut down to make it fit the lower half of a double bill when the distributor couldn’t figure out how to sell it. The original negative was lost back in the ’70s, so by the time the film had gained a passionate cult following it was no longer possible to restore it fully. The longest version (approximately 100 minutes) is considered the director’s cut and exists only as standard definition video; the butchered UK theatrical cut runs 87 minutes; and the new “Final Cut” is 94 minutes. The latter restores the original structure, while tightening things up. The theatrical cut reduces Sergeant Howie’s stay on Summerisle to a single night, eliminating the careful development of his discoveries about the nature of the islanders’ Pagan beliefs.

The set repeats all the extras from earlier editions, including the commentary on the director’s cut, a documentary by Mark Kermode, and interviews with director Hardy and star Christopher Lee. As if all that weren’t enough, Paul Giovanni’s wonderful score is included on a CD.

The Masters Of Cinema dual-format release of The White Reindeer uses a 4K restoration, which despite a damaged source is visually impressive. The short (68 minute) feature is supplemented with a commentary from Kat Ellinger, a video essay from writer Amy Simmons about witches in Nordic cinema, Blomberg’s 1947 documentary short With the Reindeer, and some colour test footage for the feature (which was ultimately shot in black-and-white).

The BFI fill out their dual-format release with a commentary from Vic Pratt and William Fowler on Secret Rites; a 1924 silent short, The Witch’s Fiddle; a 1957 television piece featuring both Gerald Gardner and Margaret Murray; a short documentary from 1970 about the counter-culture in Notting Hill; and a 1968 experimental short by Blood on Satan’s Claw writer Robert Wynne-Simmons which transplants William Blake’s mystical visionary poetry to contemporary London, displaying the deep roots of English revolutionary political thought.

Comments