Indicator’s Hammer Vol. 4: Faces of Fear

I’ve made it clear a number of times here that Indicator is one of my favourite disk labels. Apparently I’m not alone. Gary Tooze at DVD Beaver recently stated that “Indicator are the best BD production company in the world.” That comment came in response to the latest of Indicator’s Hammer box sets, volume four, Faces of Fear. I’ve been a big fan of this series, but in accord with Tooze, I’d say this is the most satisfying set yet. I’d been looking forward to it because it contains two of my favourite Hammer titles – Seth Holt’s Taste of Fear and Joseph Losey’s The Damned – but also because it includes two films from the height of the company’s Gothic output which, for reasons I’m not sure of, I had never seen before. All four movies receive Indicator’s impeccable, and thorough, treatment with, if anything, even more substantial supplements than ever.

First, the Gothics …

*

The Revenge of Frankenstein (Terence Fisher, 1958)

Hammer wasted no time when it became apparent that they had a big success with the first of their colourful Gothic horrors, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). Not only did they assign writer Jimmy Sangster and director Terence Fisher to revive Dracula (1958), they immediately set the pair to make a direct sequel to Curse. Sangster was a fast and prolific writer and the studio already had a creative assembly line up and running, with Sangster and Fisher strongly supported by production designer Bernard Robinson and cinematographer Jack Asher. As with the great Hollywood studios, this team established a distinctive look and tone (frequently enhanced by James Bernard’s romantic symphonic scores), which was carried through many movies in the following decade … even those made by others.

Sangster’s initial problem was how to deal with the fact that Curse had ended with the Baron going to the guillotine. His solution was simple and elegant. The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) opens with the Baron (Peter Cushing in what became one of his signature roles) being led to the guillotine by a priest and a hunchbacked prison attendant. As the priest drones on, they mount the platform and we catch a very brief glance exchanged between the attendant and the masked executioner. The camera pans up to the blade of the guillotine … for a second we hear a scuffle below … and the blade drops.

There’s a match cut to a couple of full mugs being slapped down on the counter of a busy tavern, and we meet a pair of drunken ruffians, Fritz (Lionel Jeffries) and Kurt (Michael Ripper), with Fritz trying to persuade Kurt to accompany him on a job. Kurt only acquiesces at the mention of a certain amount of money. We next find them digging up a fresh grave by moonlight. On the coffin lid is carved the name Baron Frankenstein. The body snatchers rip the lid off and draw back in shock – inside is the headless corpse of the priest. A voice from the shadows surprises them, and the Baron steps forward. Kurt runs away and Fritz drops dead from a heart attack.

Three years later, the Baron has established himself in Carlsbruck as a very popular doctor to the wealthy, who also does charity work in a filthy hospital for the poor. The former gives him an excellent income, the latter a reputation for philanthropy and a steady supply of body parts for his experiments. This Doctor Stein has offended the local medical establishment by refusing to join their council and they send a delegation to confront him. He dismisses them with aristocratic contempt, but one of the visitors, Dr. Hans Kleve (Francis Matthews), has recognized the Baron’s true identity. When he visits the Baron, Frankenstein initially thinks he’s being blackmailed, but it turns out that Kleve has his own ambitions and wants to become an acolyte.

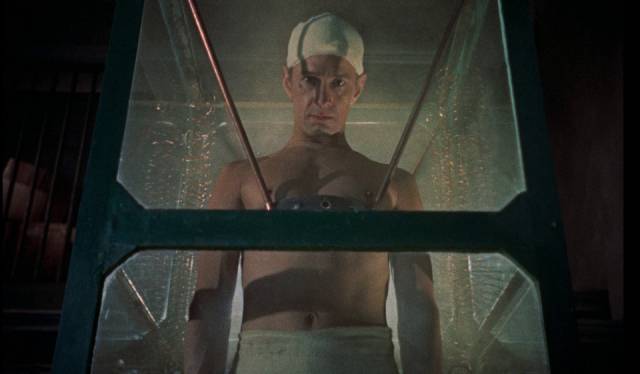

Taken to a secret laboratory, Kleve discovers that Frankenstein has created a much more elegant creature (Michael Gwynn), into which he plans to transplant the brain of the hunchbacked assistant (Oscar Quitak) who helped him escape the guillotine. Of course, these things never go as planned. Although initially it seems to be a success, the creature is vulnerable. Before full recovery from the operation, any trauma to the brain could trigger atavistic cravings to eat human flesh.

Enter Margaret (Eunice Grayson), the niece of one of Dr. Stein’s society clients. A well-meaning do-gooder who has begun volunteering at the charity hospital (combining condescension and a queasy distrust of the filthy patients), she discovers the mystery patient in a locked attic room and sympathizes with the sensitive soul who is cruelly strapped to the bed (for his own good, of course, to prevent the risk of that brain trauma). To make him more comfortable, she loosens his straps and once he’s alone, he escapes through a window and makes his way to the secret lab. As he stuffs his own old deformed body into the furnace, he’s interrupted by the coarse landlord and, inevitably, a fight triggers the feared reversion. Even as he transforms into a flesh-eating monster, the brain retains an awareness of its former identity. Its inner struggle makes it pathetic rather than horrifying.

Once again, with his careful plans to perfect man collapsing in a shambles, Frankenstein has to flee … with Kleve as his partner, he establishes himself again, this time as a successful Harley Street specialist in London.

I was surprised to realize as I watched The Revenge of Frankenstein that I’d never seen it before. And to discover that it’s one of Hammer’s best Gothics. As effective as the first movie was, it was somewhat crude. This sequel is much more elegant, with a more complex and interesting conception of the creature (both Quitak and Gwynn give sympathetic performances). The part that class plays in the narrative is also interesting, with Frankenstein standing apart from both upper and lower classes, exploiting both for what he can get from them to further his plan to “improve” mankind. The crass banality of the wealthy and the crude ignorance of the poor suggest a justification for his work. But ultimately his callous exploitation of the poor exposes the sociopathic basis of his monstrous plans; he cuts perfectly healthy limbs off bodies for bogus “medical” reasons and the violence he finally experiences in the poor ward is entirely earned.

The biggest weakness in the movie is the character of Margaret. Her combination of condescension and naivete signals that she is actually little more than a plot contrivance invented by Sangster to set in motion the second half’s descent into horror and mayhem. Gayson gives it a valiant try, but the character remains rather inert in a movie packed with lively supporting performances.

On the other hand, there are some wonderful comic touches. When Frankenstein gives Kleve a tour of the lab, he displays what he presents as an artificial brain – a series of tanks connected to batteries, with one tank containing the brain, another a severed arm, and a third a pair of eyes mounted on a kind of gimbal. When the Baron lights a match, the eyes follow it as he moves it close to the arm and the arm struggles to retreat from the flame. The disembodied eyes express a surprising mix of comic invention and distress.

Although Sangster made such an effective transition from Curse to Revenge, the narrative and thematic potential he built into the ending of the sequel was unfortunately not followed up in the belated second sequel, Freddie Francis’ dull The Evil of Frankenstein (1964). Rather than follow the Baron into London society, it returns him to small town Mittel Europe; and rather than explore the idea that he is now his own creature, having had his brain transplanted by Kleve into another created body, he’s just his old self reanimating his original creature.

Once again, Bernard Robinson has constructed atmospheric sets which belie the film’s still relatively small budget, and Jack Asher photographs them with expressive lighting and colour. But this time, James Bernard’s big sound has been replaced by a quieter, more subtle score by Leonard Salzedo, which adds to the air of overall elegance (which is not intended as a slight to Bernard, whose scores are always effective).

*

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (Terence Fisher, 1960)

Terence Fisher made five features and nine television episodes in the twenty-six months between The Revenge of Frankenstein and The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (1960) … in fact he almost maintained that pace until the end of his career with Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974). Although he occasionally strayed from Hammer, most of his work was for the studio … perhaps because it was a secure home, perhaps because the budgets he found elsewhere were even less adequate. (He made Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace for a German company; The Earth Dies Screaming for prolific low-budget producer Lippert Films; and his two most entertaining non-Hammers – Island of Terror and Night of the Big Heat – for producer Tom Blakeley at the very minor Planet Film Productions.)

Although there were other able directors at Hammer, like Don Sharp and John Gilling, Fisher was one of the defining talents which kept the company popular internationally until its decline and eventual disappearance in the mid-’70s. He made some fifteen of the key Gothics in as many years, though repetition occasionally resulted in movies which, despite their production values, were somewhat lacklustre as entertainment. A good company man, Fisher would tackle whatever assignment was handed to him.

It was known that he was not particularly fond of Jimmy Sangster’s writing – Sangster could produce pretty leaden dialogue, which was often polished by other writers, and weakly sketched characters (like Margaret in The Revenge of Frankenstein) – so it may have seemed like a step up when he was handed a script by Wolf Mankowitz, a very successful novelist, playwright and screenwriter whose work encompassed a range of genres (just the year before, Val Guest had made an excellent film from Mankowitz’s play Expresso Bongo [1959]).

Mankowitz had taken Robert Louis Stevenson’s very familiar 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde and attempted to wring a new angle from it. The script is more literate than Sangster’s usual grand guignol, but it falters dramatically, and is further compromised by an awkward dual performance by Paul Massie in the title role. Stevenson’s original is a horror-inflected satire on the extremes of Victorian repression and hypocrisy. The doctor is convinced that it should be possible to excise the primitive, animalistic part of human beings, thus giving full control to the “good” in all of us. The end result of his experiments reveals just how much more powerful the animal side of our nature is than the angelic, and that society can only function by maintaining some kind of balance between the two.

Mankowitz begins from Stevenson’s first premise, but it quickly becomes clear that the stuffy Jekyll is actually trying to throw off the social constraints he feels stifled by. Rather than trying to cut the dark side out, there’s a part of him that wants to be free to express that side. Ironically, Mankowitz does away entirely with the idea of Victorian propriety. He sets his script in an odd fin de siecle London which seems more like Paris, with opulent, decadent clubs where Can Can dancers flash their bloomers and the exotic Maria (Norma Marla), dressed in almost nothing, frolics with a big snake – that number ends unsettlingly with her literally giving the snake head! In other words, we’re in a society which itself has already thrown off all restraints; Jekyll is stifled by his own outmoded morality, well aware of all the fun everyone else is engaged in.

That fun includes Jekyll’s wife Kitty (Dawn Addams) pursuing an open affair with Paul Allen (Christopher Lee), an utterly debauched young roué, who is in the habit of paying his debts by squeezing money from Jekyll through Kitty. When Jekyll comes up with his formula (which he shoots into a vein like an addict, instead of drinking from a steaming beaker), he becomes a reflection of Paul, or rather an exaggeration of him – even Paul is shocked when Hyde almost beats a pimp to death in the club (a small early and distinctive role for Oliver Reed). Paul is also disconcerted when Hyde brazenly moves in on the dancer Maria, who has been inaccessible to him because she only makes herself available to princes and other nobility.

Through Hyde, Jekyll gets back at everyone who has offended his former propriety – he uses and abuses Maria, destroys Paul and – in the movie’s most uncomfortable scene – rapes Kitty, who then commits suicide. As in the original story, Jekyll gets progressively weaker while the energetic Hyde gains the ability to take control even without the drug. He seems on track to take over completely … until the usual censorship requirements necessitate an abrupt and dramatically weak final reversal. But given just how blatantly and enthusiastically immoral the society depicted is, it seems a bit unfair to end up punishing the pathetic Jekyll for having indulged like everyone else.

As always, production values are good and most of the cast throw themselves into it with gusto – particularly Addams and Lee – but Massie is dull as the stuffy Jekyll and we’re rather glad when he unleashes the gleefully malicious Hyde. In another attempt to overturn the usual pattern of the story, Jekyll has awkwardly fake facial hair, while Hyde, rather than looking primitive and animalistic, is handsome and clean shaven (a nod perhaps to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray) … you have to wonder where Jekyll’s hair goes in the meantime.

*

Taste of Fear (aka Scream of Fear, Seth Holt, 1961)

Jimmy Sangster himself was not a big fan of the Gothics he helped to launch and maintain. Inspired by a viewing of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Diaboliques (1955), he found a genre more to his liking – the contemporary psycho-thriller, which had been given a huge boost with the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s aptly named Psycho in 1960. Sangster quickly wrote a script on spec and shopped it around without much luck before finally taking it to Hammer. The company snapped it up, initiating a new stream parallel to the Gothics which also continued through the next decade.

Realizing that this was a departure from what was currently giving the company success, Hammer hired a new director for the project. Seth Holt was a successful editor, having cut several notable Ealing films and most recently Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). Holt had only one previous directing credit, the excellent British noir Nowhere to Go (1958), but he proved an excellent choice for Sangster’s project (the writer was also given an opportunity to produce the low-budget feature).

Taste of Fear (1961), retitled Scream of Fear in the U.S., is creepy and suspenseful, loaded with twists and red herrings to a degree which might easily have tipped over into genre parody if not for Holt’s taut, atmospheric direction, Douglas Slocombe’s moody black-and-white photography, and a cast which commits to the story wholeheartedly.

The credit sequence, whose meaning only becomes clear at the film’s climax, has police dragging a lake and finding a young woman’s drowned body. Although filmed in a familiar Hammer location in England, the scene is enhanced with an effective matte painting which makes it convincingly Swiss. From this, we cut to the airport at Nice where chauffeur Robert (Ronald Lewis) meets Penny Appleby (Susan Strasberg), a young woman in a wheelchair. He explains that her father, whom she hasn’t seen in ten years, isn’t there to meet her because he had to take a sudden business trip.

Arriving at her father’s villa in Cap d’Antibes, Penny seems wary as she meets her stepmother Jane (Ann Todd). Tension is immediately apparent, but it seems more than just the normal complications arising from divorce and a second marriage. These tensions increase with the intrusive presence of Dr. Pierre Gerrard (Christopher Lee); Penny suspects an illicit relationship between him and Jane, and the absence of her father takes on sinister undertones … which erupt into something more concrete when she sees light flickering in the summer house across the patio at night. She wheels herself over, enters, and by candlelight sees the body of her father sitting in a chair, his eyes staring blankly.

Panicked, she rushes away and the wheel of her chair slips over the edge of the murky swimming pool. She’s only just saved from drowning by Robert. Naturally, when she recovers her senses and tries to convince Robert, Jane and Gerrard of what she saw, they all head to the summer house … and find it locked and empty. Behind Jane’s back, Penny forges an alliance with Robert, who seems willing to believe her suspicions that Jane and Gerrard have killed her father and are now trying to drive her mad so that his estate will be free for Jane to inherit.

There are more appearances of the dead body, more instances of gaslighting, and as the film progresses, more revelations which undermine what we think is happening. Sangster deftly fools us again and again with reversals, betrayals and well placed red herrings. If the narrative ultimately lacks the plausibility of Psycho, Sangster and Holt play the game deftly, and perhaps more importantly, fairly. The string of climactic revelations are completely satisfying.

Taste of Fear established the formula for Hammer’s psychological thrillers and remains the best of them.

*

The Damned (Joseph Losey, 1962)

And finally, the crowning glory of the set – perhaps the least typical of all the studio’s productions, a film which is not perfect, but is nonetheless fascinating for its idiosyncrasies and the ways in which it plays with genre. The Damned (aka These Are the Damned, 1962), based on a novel by H.L. Lawrence, is a mixture of social commentary, anti-nuclear polemic, science fiction, horror and existential nightmare. The political element sets it completely apart from the rest of the studio’s output, and at least in part explains the fumbled handling of its release and distribution.

But the production’s biggest problem were the conflicts between Hammer and director Joseph Losey. In exile from the U.S. after his run-ins with the House Un-American Activities Committee in the early ’50s, Losey was still forging his auteurist identity at the time and was not at all in sympathy with the science fiction elements of the project. He would only come fully into his own the next year when he teamed up with Harold Pinter for The Servant (1963), the unsettling psychological drama which launched a string of successful, arty features over the next two decades (with a scattering of strange excursions into camp – Modesty Blaise, Boom, Secret Ceremony – which may actually be his most purely entertaining movies).

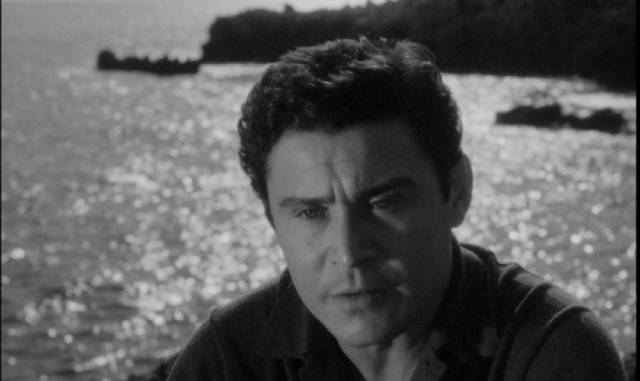

The Damned weaves several narrative threads together, each adding thematic layers to a deeply pessimistic depiction of a society descending into self-destructive madness. Simon Wells (Macdonald Carey) has abandoned his life as a businessman in the States, opting out like David Sumner in Straw Dogs (1971), looking for peace and finding something much darker. Visiting the decaying coastal town of Weymouth, he tries to pick up the much younger Joan (Shirley Anne Field), only to get beaten and robbed by a biker gang led by her brother King (Oliver Reed). Helped to a nearby hotel, he meets artist Freya (Viveca Lindfors) and her former lover, the government bureaucrat Bernard (Alexander Knox). Freya and Bernard have been having a testy conversation about secrecy and cynicism; interrupting, Simon comments that he certainly didn’t expect to encounter violence in England – that was one of the reasons he left the States. Bernard responds ruefully that, indeed, the country has joined the modern age.

The fates of these various characters become entwined when Simon convinces Joan to escape the gang and the pair are pursued by King, eventually leading them to hide out at Freya’s clifftop cottage and studio, where she sculpts nightmarish portents of the coming apocalypse. Discovered there, Simon and Joan find themselves chased to a military installation; trying to escape down a dangerous cliff, they are eventually saved from the sea by a group of strange children who live deep underground, isolated from all human contact by a project run by Bernard. Following them, King also ends up in the caves.

What they learn too late is that the children are radioactive and that contact with them will prove fatal. (It was the fanciful conceit of the radioactive children which Losey had a problem with; yet even if they’re scientifically bogus, they give the film enormous potency.) Born to mothers who were contaminated by a nuclear accident, the children are, Bernard believes, immune to further damage and thus may be the only survivors of what he believes is an inevitable nuclear holocaust. This certainty is what has put him at odds with Freya; she can’t understand his fatalism, his resistance to the idea that society must find a way to avert its destructive compulsions rather than perversely embrace them.

In retrospect, it’s this pessimism which fuels the rebellious violence of King and his gang. They are little more than children who have been shown that there is no future for them to grow into responsibly and so they strike out nihilistically, while the supposedly responsible adults abdicate their obligations, not simply sitting back and allowing society to plunge off the nuclear cliff, but rather embracing the idea of complete destruction and justifying their monstrous treatment of the contaminated children as a gesture towards some kind of human survival.

There are some odd tonal inconsistencies in the film – the chilling adult seriousness of Freya and Bernard’s philosophical conflict and the even more chilling activities of the research project, which systematically denies the humanity of the children it is supposedly nurturing to carry on the human race in a world stripped of life by the horrific acts of that same humanity which seems incapable of saving itself, sit uneasily beside the contrivance of King’s gang, which in their first scene are ironically mimicking the military regimentation of the society which denies them hope. The visuals are striking, but the gang lack a degree of realism – they have a thematic purpose, but are not entirely dramatically plausible.

Then there’s an issue which may not have bothered viewers at the time, but stands out clearly now. While Simon is obviously intended to serve as an audience surrogate, the character through whose eyes we gradually discover what’s going on, his pursuit of Joan makes him seem like a predatory creep. She does confront him about this, challenging his view of her as a mere sex object, but nonetheless goes along with him as perhaps the only option she has for escaping King’s incestuous possessiveness. But she’s exchanging one undesirable relationship for another which doesn’t seem much better.

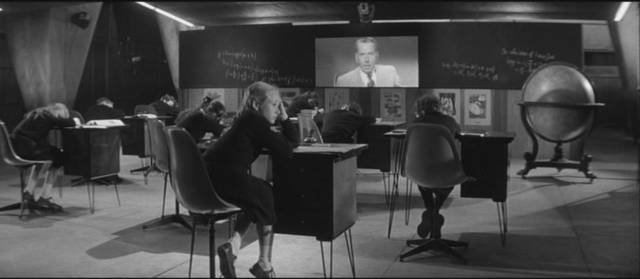

Apart from some dramatic awkwardness, The Damned is a superb visual work, at times suffused with austere beauty – Freya’s sculptures overlooking the sea (created by the artist Elisabeth Frink), the children’s underground bunker where their only contact with other people is via the big television screen through which Bernard and his team educate them, and at the climax Losey’s impressive use of helicopters resembling sinister, predatory birds which make escape impossible. This imagery is some of the best work of the great cinematographer Arthur Grant, who did for Hammer in black-and-white what Jack Asher did in colour.

Apart from the film’s intrinsic value as a dark science fiction allegory, it is an interesting study in the tensions between a studio which was working very hard to establish and maintain its own creative signatures and a filmmaker determined to hold on to his independence and forge a clear creative identity rooted in his own political and aesthetic interests. The Damned doesn’t hold together with complete coherence – the limits of schedule and budget, and the fact that writer Evan Jones was working on the script throughout the shoot, all but guaranteed that Losey wouldn’t be able to do everything he wanted – and what resulted left Hammer confused. This, unlike their other productions, touched closely on serious contemporary social issues – it was a movie with a deeply pessimistic message, leaving its audience with a sense of hopelessness. No wonder they held it back for a couple of years and then dumped it as the bottom half of a double bill with nine minutes chopped out of it. For a long time it was really difficult to see, but over the ensuing decades it has gained both fans and critical respect.

*

Indicator have outdone themselves with this fourth set of Hammer features. Once again, the disks present exceptional transfers and massive quantities of supplementary material – each film gets a commentary; a retrospective evaluation by some of the usual suspects (Jonathan Rigby, Alan Barnes, Kevin Lyons), who provide background and critical evaluations; short featurettes on key female performers; an analysis of each film’s score by David Huckvale; interviews with various cast and crew members; audio interviews with Sangster, Douglas Slocombe and Paul Massie; video essays on several of the films … and more. Most substantially, The Damned comes as a two-disk set which includes the 87-minute U.K. theatrical cut and the 96-minute “complete” version – both of which contain the crucially altered ending imposed by the studio over Losey’s objections: he originally had Freya gunned down by a hovering helicopter, erased by the faceless power of a state unable to free itself from its destructive impulses, but Hammer insisted on making it personal, with her former lover Bernard doing the job in what remains an awkward inserted cut.

Indicator’s Hammer Vol. 4: Faces of Fear is one of the highlights of 2019.

Comments