Seeing in the New Year

No doubt it has something to do with getting older, but here at the start of the third decade of the century, I found myself looking back instead of forward. Following what has long been a tradition, I went to my friend Steve’s for New Year’s Eve. After a lively get together with the family featuring a lot of eating and drinking (a traditional roast beef dinner, with Yorkshire pudding accompanied by red wine and, perhaps not so traditional, two different home-made chicken curries, followed by a traditional English trifle), Steve and I settled down to watch no less than three movies, the most recent from 1974.

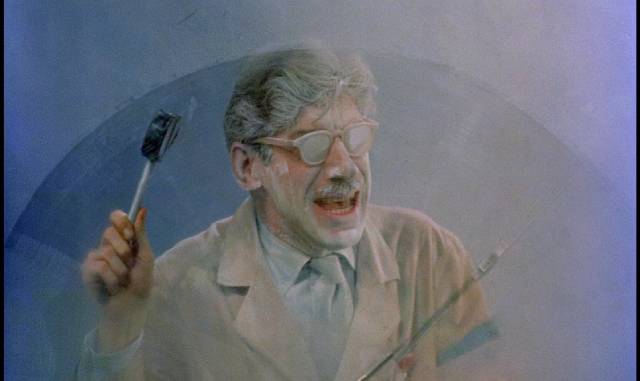

We started with Herbert L. Strock’s Gog (1954), a restoration by the 3D Foundation, released on Blu-ray four years ago by Kino. I had seen the movie just once before, pan-and-scanned in black-and-white on television in the late ’60s, and recalled only two things – a couple of slightly silly robots, and the fact that it was pretty dull. But that memory didn’t prevent me wanting to see it in widescreen, colour and, most importantly, 3D. With the high quality of digital technology, I’m willing to watch anything from the first eruption of 3D in 1953-54.

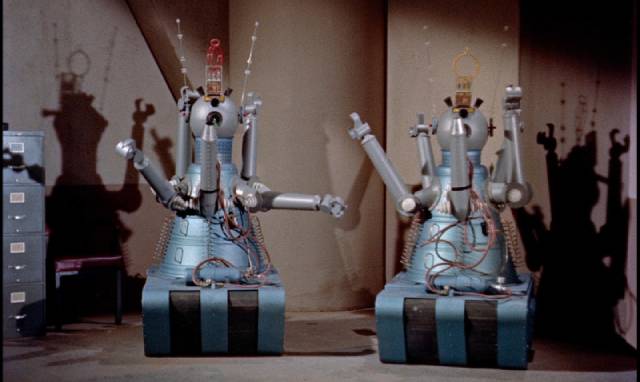

Both my memories were borne out as we watched Gog. There are a couple of rather silly robots and it is pretty dull. When researchers at a secret desert laboratory begin dying in mysterious ways, investigator David Sheppard (Richard Egan) arrives to, well, investigate. He gets a tour of the lab from old flame Joanna Merritt (Constance Dowling) and meets the staff overseen by administrator Dr. Van Ness (Herbert Marshall). The lab is developing technologies for space flight, including artificial intelligence and suspended animation. It’s all controlled by a big central computer and powered by a nuclear reactor.

Strock and writers Tom Taggart and Richard G. Taylor, working from a story by producer Ivan Tors, aren’t aiming for mystery or suspense as the movie begins with a couple of scientists being killed by their own equipment. The culprit is the technology itself. There are other deaths and eventually one of the robots (named Gog and Magog for some reason, though the meaning of the Biblical reference to barbarian tribes doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the story) initiates a core meltdown which comes close to destroying the lab.

It turns out the central computer has been hacked by a plane flying overhead in the stratosphere – of unknown origin, but no doubt sent by the Russkies.

Steve pointed out that the lab itself – wheel shaped, with levels coded for different functions and access limited by colour-coded security clearances, with a reactor on the lowest level capable of vaporizing the whole installation – is surprisingly reminiscent of Project Wildfire in The Andromeda Strain. Maybe Michael Crichton saw Gog when he was a kid and it lingered in the back of his imagination. Like James Olson in Robert Wise’s movie adaptation, Richard Egan has to fight off the lab’s defences (in this case Gog) in order to shut down the reactor before everyone is killed.

Strock’s use of 3D is surprisingly restrained (or is that simply unimaginative?), with little eye poking. Mostly, it just gives a sense of space to the rather bland sets.

Feeling a bit disappointed, we moved on hopefully to a feature neither of us had previously seen, but which I recall reading about back in the ’70s – Paul Maslansky’s Sugar Hill (1974). I’m not sure why it took so long to catch up with it – it must’ve been released on VHS at some point, but I never came across it – particularly since the hook seemed so appealing. What’s not to like about a blaxploitation zombie movie?

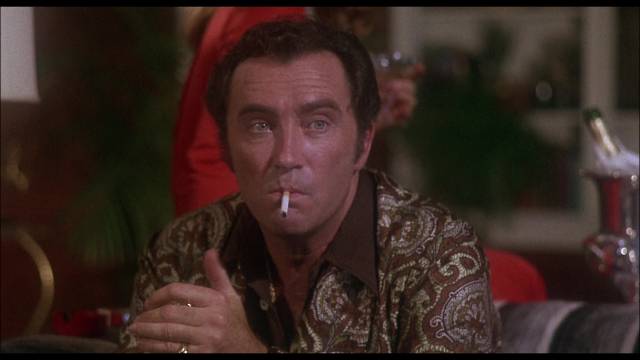

Strangely, this was the sole directorial effort of Maslansky, who was a successful producer with a rather eclectic list of credits – from Michael Reeves’ The She Beast and Gary Sherman’s Death Line to the Police Academy movies and Fred Schepisi’s The Russia House. I have no idea how he came to direct Sugar Hill, but his work is efficient if not terribly dynamic. When gangster Morgan (Robert Quarry) kills club owner Langston (Larry Don Johnson) because he refuses to sell Club Haiti to him, Langston’s girlfriend Diana “Sugar” Hill (Marki Bey) heads back to the old family estate to find Mama Maitresse (Zara Cully), whom she asks for help in getting revenge.

Off in the swamp, Mama summons Baron Samedi (Don Pedro Colley) who, apparently more for his own amusement than any substantial payment (he scoffs when Sugar offers him her soul), agrees to help her out. With flashes of lightning and lots of ground mist, Samedi summons the dead from a nearby cemetery. These are mostly slaves who died from plague on the ships carrying them from Africa, buried in the chains which had weighed them down in life. A cross between traditional voodoo zombies and the more modern living dead, with gaunt features and silver eyes which catch the light in a creepy way, they wield machetes as they go about Sugar’s business.

While Sugar pretends to be negotiating with Morgan for the sale of the club, the zombies kill off his gang one by one. Detective Valentine (Richard Lawson) begins to catch on, suspecting some supernatural agency is involved, but he’s always a step behind and Sugar’s revenge eventually wipes out the entire gang. Samedi, when it’s over, is happy to take Morgan’s racist girlfriend Celeste (Betty Anne Rees) in payment and disappears with a hearty laugh into more lightning and ground mist.

Although Maslansky’s direction isn’t what you’d call inspired and the pace is quite leisurely, Robert C. Jessup’s photography supplies some effective atmosphere, particularly with the gleaming eyes of the zombies. Marki Bey is an appealing heroine, Robert Quarry a good sleazy villain, and Zara Cully an impressive voodoo priestess. But the best thing in the movie is Don Pedro Colley’s enthusiastic Baron Samedi, who views all the mayhem with robust humour. It’s a mystery why he didn’t have a career like Richard Roundtree or William Marshall, with almost nothing but TV parts after this.

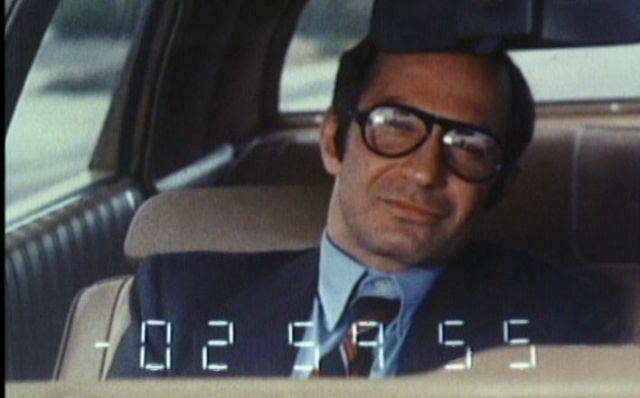

By the time Samedi disappeared back into the swamp, it was approaching midnight and we popped another disk into the player. This was Michael Crichton’s directorial debut, a made-for-television adaptation of one of his own early novels, published under the pseudonym John Lange. When Crichton sold the rights to Binary to ABC, it was on the condition that they let him direct. They agreed, but only if someone else wrote the script. That job went to prolific TV writer Robert Dozier, who turned Crichton’s tight thriller into a spare, fast-paced procedural with little room for the characters to breathe.

Pursuit (1972) begins with a surprisingly violent prologue in which a military convoy is attacked in the middle of the night, all personnel machine-gunned to death, and two large cylinders stolen. Agent Steven Graves (Ben Gazzara) is called in and quickly pieces things together. What was stolen were the binary components of a powerful nerve gas, enough to kill a million people. The thief is a right-wing businessman named James Wright (E.G. Marshall) who wants to save the country by hitting the reset button – which means wiping out much of San Diego during the presidential-year ruling-party convention just as the President arrives.

Graves and his bosses know what’s going on; they even know where the canisters are – in a high rise apartment rigged with booby traps and plastic explosive scheduled to blow the tanks, mixing the binary components which will then pour out over the city. The problem is how to disarm it all when the room containing the device has already been flooded with the gas.

It all takes place within less than a day, an on-screen digital clock counting down the hours and minutes as Graves figures out how to prevent a disaster. Crichton manages the mechanics of it all with impersonal efficiency, leaving it up to the actors to inject sufficient human interest to keep the stakes high. Gazzara is your typical pragmatic hero, chafing at bureaucratic obstacles, and Marshall is very good as a calm fanatic willing to sacrifice himself if it means an end to all the liberal nonsense which is ruining the country. Though political paranoia remains largely subtext propping up the plot mechanics, Pursuit is an effective if minor contribution to the distinctive ’70s genre of cynical political thrillers.

And by the time it was over we were almost an hour into the new year … a year doomed to be dominated by increasingly deranged American presidential politics. With the Republicans working so hard to stir up right-wing extremism, maybe the culmination of the evening with its apocalyptic right-wing death-wish fantasy wasn’t so much a looking-back after all.

*

All three disks are from Kino Lorber and feature commentaries and, in the case of Gog and Sugar Hill, additional interviews.

Comments

A good time was had by all. 🙂

Let’s hope the year just keeps getting better!