Year End 2019

For a number of reasons, it gets harder every year to compile a “best of” list. As the years pass, I see fewer and fewer new movies. Back in the day, I’d go to the theatre hundreds of times a year – this past year, I went just once! Even as I write that, I find it hard to believe. A friend and I went to see Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, a mesmerizing work full of madness and sexual tension whose meanings seemed impenetrable even as I was utterly immersed in its intensely visceral imagery. It was only afterwards that I read several commentaries which deciphered all (or at least many) of the mythological references which went right by me while I was watching. Enthralling and frustrating in equal measure, it’s a movie I’ll definitely watch again, though I’m not sure I’ll ever really grasp it … or even like it.

So that was it for new theatrical releases. On the other hand, at home I watched more than five hundred movies, mostly on Blu-ray, occasionally on DVD, and a few times off the Internet, either as a download or streaming. There’s a huge amount available of varying quality and possibly dubious legality, but sometimes it’s the only way to find something. Trying to declare which few of all these movies were “the best” is absurd, a purely subjective opinion of little use to anyone but myself – so to be purely arbitrary, let’s say Criterion’s three-disk set of Abbas Kiarostami’s masterpiece The Koker Trilogy and Helmut Kautner’s 1944 romance Unter den Brucken, available on the Internet Archive.

Disks, despite having been proclaimed all but dead for at least a decade, seem to be thriving. It’s impossible to keep up with the flood of releases as various companies seem to dig up more and more obscure and forgotten titles as well as reviving and restoring better known movies. The biggest change from a decade or so ago is that much of this work is being done by smaller, niche companies rather than major distributors. The big companies have shied away from the archival work they did back in the early days of DVD, and that was the original reason people began predicting that physical media would soon disappear. From a financial point of view, streaming makes sense to large corporations because it keeps their costs down (and incidentally allows them to maintain more control of their product). But there are still a large number of movie lovers who prefer to own their own copies and the big companies have off-loaded the costs and labour involved by licensing an increasing number of titles to boutique labels.

Because these companies provide a steady supply of titles spanning the entire history of cinema, I find the ratio of older movies to newer releases in my viewing to be very high. So, no, I’m in no position to offer an opinion of what are the best movies of 2019 … and since a lot of what I see are disks released in previous years, I can’t even offer a useful opinion on this year’s best disks. (Criterion is the only company that sends me review copies of new releases, though Indicator did offer to supply me – unfortunately they only send out check disks, not the complete final package, so I had to turn them down; because I love their packaging and booklets, I’ll have to continue buying them.) The list below takes no account of when either the movie or the disk was released – it merely reflects my own personal, idiosyncratic viewing. I’ve organized it roughly by label, so nothing here implies any kind of hierarchy.

*

Severin

Severin specializes in genre and exploitation titles from around the world. Quality is variable, depending on the condition of sources and the degree of restoration, so you tend to take your chances – but it’s often worth the gamble because they do dig up quite a few interesting obscurities.

The Boys Next Door (Penelope Spheeris, 1984): I’d never seen Penelope Spheeris’ second dramatic feature, and knew her mostly for her music documentaries and Wayne’s World. The Boys Next Door, after an extraneous and inappropriate title sequence about serial killers, becomes the raw and intense story of a couple of disaffected working class high school graduates who, before settling down to a life of limited prospects, drive to Los Angeles and spend a weekend raising hell and killing people.

The Killing of America (Sheldon Renan, 1981): Purely by coincidence, this makes an excellent companion for Spheeris’ movie. Written by Leonard and Chieko Schrader, The Killing of America is one of the rare Mondo documentaries that argues an actual thesis – in this case, that the American founding myth of rugged individualism, rooted in the idea of resistance to the idea of community with its necessary restrictions on individual behaviour, has generated an addiction to violence which continually threatens to tear the country apart.

Viy (Konstantin Ershov & Georgiy Kropachyov, 1967): A rich and colourful 19th Century folk tale about a callow seminary student who is assaulted by imps and demons as he sits watch over the body of a beautiful young witch in a rustic chapel.

*

Vinegar Syndrome

Like Severin, Vinegar Syndrome leans towards the more disreputable end of the cinematic spectrum. In fact, it often leans even further in digging up cheap and offensive exploitation, restoring movies to look better than they ever did on a grindhouse screen. But they also manage to find obscure genre titles that you’ve likely never heard of before they show up on disk, frequently adding commentaries and featurettes.

Battle for the Lost Planet/Mutant War (Brett Piper, 1986/1988): Brett Piper is a special effects guy who turned to writing and directing in the mid-’80s, apparently in part to give himself an opportunity to indulge in old-style effects techniques – miniatures, matte paintings, stop-motion. That was the main impetus for Battle for the Lost Planet and its sequel Mutant War, both featuring petty criminal/spaceman Harry Trent (Matt Mitler), who against his own better judgment gets involved in fighting aliens and rescuing damsels-in-distress. The first movie was shot on 16mm, the second on 35mm, and while they have the usual marks of a very low budget (uneven acting, quite a bit of narrative padding), they do have some genuine charm, with Mitler an engaging lead, and some impressive effects set-pieces.

Dear Dead Delilah (John Farris, 1972): The only movie directed by John Farris, better known as the writer of books like The Fury, this is an overwrought Southern Gothic in the mould of Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte with one of the latter’s stars, Agnes Moorehead, as a wheelchair-bound, acid-tongued matriarch who invites her siblings to the old plantation to torment them by dangling a big inheritance that they have to compete for … axe murders ensue.

Decoder (Muscha, 1984): This post-punk underground feature from Germany is a kind-of sci-fi, social commentary movie with a fairly minimal, slightly murky narrative about a guy who discovers that Muzak is being used to pacify the population (like the hidden messages in John Carpenter’s They Live); he creates his own disruptive music, injecting it into public sound systems to provoke rebellion and riots – characters actually wander through documentary footage of real riots which swept through Germany in the early ’80s. The guy is played by FM Einheit from Einsturzende Neubauten, and in addition to his industrial percussive contribution, the soundtrack includes music from Soft Cell and The The. Decoder is a time capsule from a period when rebellion and social upheaval seemed possible.

*

Arrow

Arrow continues to release a substantial number of disks, ranging from pure exploitation to high art, often in well-stacked special editions featuring excellent restorations and informative supplements. This has been one of my favourite companies for years now and they never disappoint.

Ramrod (Andre De Toth, 1947): The eclectic Andre de Toth’s first western is suffused with the ambience of film noir, which was at its height a couple of years after the war. It even has Veronica Lake as a femme fatale, whose fierce independence in the face of masculine power and violence almost destroys nice guy Joel McCrea.

Property is No Longer a Theft (Elio Petri, 1973): Elio Petri’s incisive political satire elaborately dissects the ways in which Capitalism deforms individuals and undermines the relationships crucial for a functioning society.

Before We Vanish (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2017): Kurosawa’s alien invasion movie balances apocalyptic events with an intimate exploration of what it means to be human.

in Luigi Bazzoni’s The Fifth Cord (1971)

The Possessed/The Fifth Cord (Luigi Bazzoni, 1965/1971): One of the big discoveries of the year was Italian director Luigi Bazzoni, whose three giallo-esque features push the genre in the direction of post-modern abstraction. Like Petri, Bazzoni makes great use of existing locations and architecture to create tension between his alienated characters and a dehumanized society.

Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years Vol. 2 (1957-61): These five crime movies display Suzuki’s technical assurance as well as the early stages of his resistance to studio-dictated formulas. It wouldn’t be long before his tendency to experiment with style would get him kicked out of Nikkatsu, leading to his increasingly radical features from the late ’60s to the end of his career in 2005.

Bloody Birthday (Ed Hunt, 1981): Ed Hunt is one of those directors who cheerfully plows ahead regardless of the inadequacy of his budgets, making ridiculous yet entertaining movies like Starship Invasions (1977) and The Brain (1988). But his best movie didn’t need unattainable special effects; it relies on something more mundane – child actors cheerfully doing monstrous things. Three kids all born during a total eclipse are little sociopaths who, as their tenth birthday approaches, go on a murder spree in their sleepy little town. One of the best movies in the evil kids genre.

Blood Hunger (José Ramón Larraz, 1970-77): Spanish director José Ramón Larraz had an affinity for England and the English countryside, making five of his early features in a strangely feverish version of the country. Two of those five are included in this three disk set – his first feature, Whirlpool (1970), and his final English production, Vampyres (1974) – along with the Spanish feature The Coming of Sin (1977), all of which mix deviant sexuality with horror. Larraz is reminiscent of Jean Rollin and, in the third film, of Walerian Borowczyk, though he doesn’t quite achieve the poetry of either.

Female Prisoner Scorpion (Shunya Ito/Yasuharu Hasebe, 1972-73): This four-movie series stars Meiko Kaji as a woman betrayed and sent to prison where her stoic resistance to male power brings harsh retribution from the authorities and resentment and hostility from her fellow prisoners. Over the course of the series, Scorpion gains almost mythic status as a symbol of female opposition to a brutal patriarchy.

*

in Stanley Kramer’s Ship of Fools (1965)

Indicator

In just a few short years, Indicator (the disk label of Powerhouse Films) has established itself as the equal of Criterion, Arrow and the BFI as a reliable source of quality releases which showcase obscure rediscoveries and impeccably restored movies ranging from genre favourites to significant mainstream titles.

Time Without Pity (Joseph Losey, 1957): Having gone into exile after his run-in with the House Un-American Activities Committee, Joseph Losey worked pseudonymously for several years in England before signing his real name to this interesting if overwrought thriller in which an alcoholic writer returns to England just twenty-four hours before his estranged son is scheduled to hang for a murder he didn’t commit. Against his son’s fatalistic wishes, he tries desperately to get the execution stayed while he works to uncover the real murderer. The contrived script by Ben Barzman (also blacklisted) was based on a play by Emlyn Williams. The excellent cast keeps it interesting.

Ship of Fools/R.P.M. (Stanley Kramer, 1965/1970): Stanley Kramer’s best film and one of his most interesting failures both receive excellent editions. The sprawling Ship of Fools is packed with stars and multiple storylines which keep it involving as it combines high drama, soap opera and a powerful sense of impending doom on a German liner sailing from South America to Hamburg in 1933. Late ’60s campus unrest becomes a vehicle for frustrated liberalism in R.P.M., with Anthony Quinn as a hip academic who fails to forge a bridge between rebellious youth and a reactionary establishment.

in Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957)

Night of the Demon (Jacques Tourneur, 1957): Indicator produced one of its most comprehensive releases with Jacques Tourneur’s adaptation of M.R. James’ “Casting the Runes”, an atmospheric return to the kind of film Tourneur made for producer Val Lewton in the 1940s. This tale of demons and paranoia arrived in multiple versions – three different cuts, each in two different aspect ratios – along with stacks of supplements.

A Dandy in Aspic (Anthony Mann & Laurence Harvey, 1968): Anthony Mann’s final feature, completed after his death by star Laurence Harvey, got somewhat lost when it was released at the end of the bleak anti-Bond espionage trend in the late-’60s, but it’s an excellent example of the genre and can hold its own with The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, The Ipcress File and Funeral in Berlin.

Bloody Terror (Norman Warren, 1976-87): While Indicator has released multi-disk sets more worthy – they’re up to four volumes of Hammer movies and two sets of William Castle’s peak-period productions – I really enjoyed the showcase they gave to British exploitation specialist Norman J. Warren with this packed five-disk set. If the movies themselves aren’t particularly ambitious, they’re colourful and made with enthusiasm.

*

BFI

My acquisition of BFI releases has declined over the past few years, partly because other companies are putting out so many titles which appeal to my taste. I only have so much time and money!

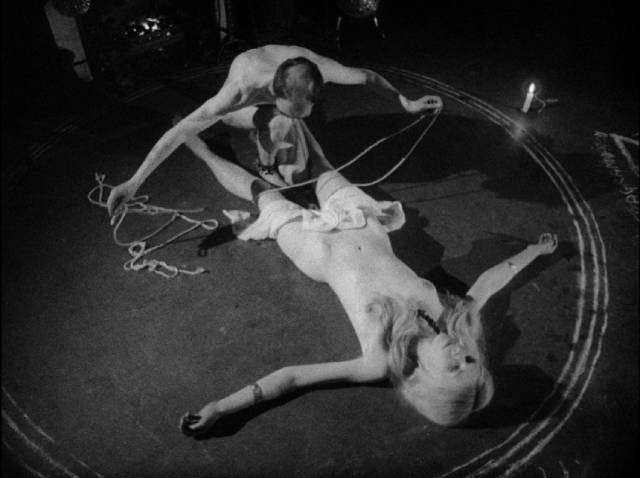

Legend of the Witches/Secret Rites (Malcolm Leigh/Derek Ford, 1970-71): This pair of exploitation documentaries, made at the end of the ’60s to cash in on both a trendy counter-culture interest in esoteric ideas and a prurient interest inspired by tabloid exaggerations about the modern revival of witchcraft, offer a fascinating look at how popular culture absorbs and transforms serious ideas. Although the two films are very different in tone, each disguises its primary concern with on-screen nudity behind supposedly sincere investigations.

Room at the Top (Jack Clayton, 1959): Jack Clayton’s adaptation of John Braine’s novel about an ambitious working class man striving to climb the economic ladder of post-war prosperity was one of the films which launched the British New Wave. That movement is represented by the BFI’s previous release of their Woodfall Films box set.

*

Eureka

Eureka, home of Masters of Cinema, like the BFI, hovers around the perimeter of my disk buying … I usually wait for one of their fairly regular sales to pick up a few new titles. Among other things (specifically a small stack of older releases), their special edition of The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith is currently waiting on the shelf, and I’ll definitely be picking up Raining in the Mountain, the next title in their tantalizingly slow roll-out of King Hu’s work.

The Fate of Lee Khan (King Hu, 1973): Speaking of King Hu, Eureka recently released The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), the third of his “inn” movies after Come Drink With Me (1966) and Dragon Inn (1967). These films helped to define the modern martial arts genre. Smaller in scale than his epic A Touch of Zen and Legend of the Mountain, they’re an interesting mix of period espionage and spectacularly choreographed fight scenes. One of the signature elements of Hu’s wuxia films is the central position of female characters, who are tough, independent and terrific fighters … and this is also true of Lee Khan, in which the owner of the inn and her three waitresses belong to a secret resistance, kicking ass and serving food and drinks with equal dexterity.

The White Reindeer (Erik Blomberg, 1952): Finland’s first horror movie is a visually arresting mix of ethnographic documentary and folk tale, in which a woman in a small community in Lapland casts a spell to give herself power over men and becomes a shape-shifter, luring hunters to a remote valley and drinking their blood. Closely observing the way of life of reindeer herders, the film offers a distinctly different type of supernatural horror.

Troll (John Buechler, 1986)/Troll 2 (Claudio Fragasso, 1991)/Best Worst Movie (Michael Paul Stephenson, 2009): Possibly the oddest release I came across during the year is this set of two rather cheesy low-budget fantasies and a compelling documentary about the transience of celebrity, put out by a company known for prestigious releases.

Day of the Outlaw (Andre de Toth, 1959): Andre de Toth’s final western is a bleak and nihilistic film shot in remote mountain landscapes in the middle of winter. Its harshness and complete lack of romance set the tone for the anti-westerns of the ’60s.

*

Criterion

Criterion continues to maintain the prestige and quality which have been the company’s hallmark for decades, but they sometimes seem a little staid in light of more adventurous companies, reflecting their mission statement to preserve the cinematic canon. But what they do release is always impeccably presented, and usually accompanied by supplements which justify the choices they’ve made.

The Heiress (William Wyler, 1949): Among the year’s highlights is William Wyler’s best film, an adaptation of Henry James’ Washington Square. A devastating dissection of money and class in America, The Heiress is a dark, emotionally wrenching drama which offers a masterclass in literary adaptation, not only being faithful to the source, but building on it organically to expand and enrich its themes.

The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (Ozu Yasujiro, 1952): Made at the height of his powers, between Early Summer and Tokyo Story, Ozu’s The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice was previously unknown to me, but turned out to be one of his subtlest and most emotionally resonant treatments of middle class marriage in the unsettled period of post-war economic recovery. The disk includes a second feature, What Did the Lady Forget (1937), which is like a rough sketch of the later film, illustrating how his talent grew exponentially after the war.

Panique (Julien Duvivier, 1946): Julien Duvivier’s adaptation of a Georges Simenon novel presents a devastating portrait of post-war French society: dark, paranoid, shot through with repression, suspicion and vindictiveness. This bleak, sordid story gave Michel Simon one of his finest roles.

The Koker Trilogy (Abbas Kiarostami, 1987-94): One of the masterworks of world cinema, Kiarostami’s three interconnected films – Where Is the Friend’s House?, And Life Goes On, and Through the Olive Trees – move from the raw emotional power of neorealism through a deepening self-reflexive examination of the nature of cinema itself, all the while dramatically documenting life in post-revolution Iran. A work of towering power and heart-breaking intimacy.

*

Synapse

Synapse is on a par with Severin, with a focus on genre movies.

Suspiria/Tenebrae (Dario Argento, 1977/82): Although not released in 2019, I caught up with Synapse’s Blu-rays of my two favourite Dario Argento features this year. For me, Tenebrae is Argento’s most perfectly formed giallo, while Suspiria remains one of the most hypnotic and visually beautiful horror films ever made. The 4K restoration of the latter is absolutely stunning.

*

Kino Lorber

Kino Lorber has been releasing disks at an amazing rate, with titles in every conceivable genre, frequently with excellent image and informative extras. They’ve also been releasing quite a few 3D disks, both from the first boom in the early 1950s and from later revivals of the technique (I recently watched Charles Band’s entertaining B horror Parasite [1982] at a friend’s and was reminded of just how good and innovative cinematographer Mac Ahlberg’s use of the format was in this and Band’s Metalstorm [1983]).

The Maze (William Cameron Menzies, 1953): William Cameron Menzies’ daffy 3D Gothic horror, The Maze, is my favourite revival from the golden age. Fog-bound studio sets, the dank halls of a remote Scottish castle, and an endearingly absurd monster all look terrific in 3D.

Fantomas (Andre Hunebelle, 1964-67): Despite diminishing returns over a three-movie run, Andre Hunebelle’s revival of the classic French criminal mastermind Fantomas is a colourful, tongue-in-cheek response to the success of the Bond series. Jean Marais has charm in the duel role of Fantomas and his newspaperman nemesis Fandor, and the movies feature some pretty impressive stunt work.

*

Shout! Factory

Shout! Factory and its sub-label Scream Factory continue to be a genre fan’s dream company, releasing an endless stream of special editions of horror and sci-fi titles from the ’50s on, many in extras-laden two-disk sets.

Grave of the Vampire (John Hayes, 1972): I first saw John Hayes’ vampire movie on its original theatrical release and waited years to see it again, having to settle for dreadful public domain DVDs until Shout! brought out a Blu-ray with a decent hi-def transfer and two commentaries. The film holds up as a key release from the fertile low-budget horror period of the ’70s.

The Monolith Monsters (John Sherwood, 1957): Another favourite first seen in the ’70s (on television), The Monolith Monsters is the best Jack Arnold movie not directed by Jack Arnold – it has those great Arnold desert locations and a tough, no-nonsense style which makes its abstract alien menace (deadly crystals from a meteor) one of the most effective monsters from the ’50s.

This Island Earth (Joseph Newman, 1955): Universal’s sole bid to match the big budget sci-fi epics of MGM (Forbidden Planet) and Paramount (War of the Worlds), may have an awkward structure and script shortcomings, but Shout!’s 4K restoration and extensive supplements rescue the movie from the ignominious desecration inflicted on it by the insufferably smug MST3K crew.

Quatermass II/Quatermass and the Pit (Val Guest/Roy Ward Baker, 1957/1967): After a few years of waiting, Hammer’s second and third Quatermass features finally turned up to join Kino’s The Quatermass Xperiment on Blu-ray. Although I wasn’t entirely thrilled by the transfer on Quatermass II, it’s great to have the whole trilogy on Blu-ray with new and archival commentaries and featurettes.

Dracula (John Badham, 1979): Not only does Shout! provide a lot of supplements on their two-disk special edition of what remains the best of the tragically romantic vampire movies, they include two different transfers with radically different colour timing – one represents the original brightly saturated theatrical release, the other a later revised, desaturated version preferred by director John Badham, which has been the standard home video version for three decades. Both have their points and which one appeals to individual viewers is a matter of personal taste.

Suburbia (Penelope Spheeris, 1983): I checked out Penelope Spheeris’ first dramatic feature right after watching her second, The Boys Next Door, and it’s even better. A bunch of kids escaping from various lousy family situations form their own impromptu family, squatting in a derelict house, stealing food, and hanging out on the fringes of Los Angeles’ punk scene. They provide mutual support and validation as the police and “respectable citizens” view them as pariahs – like the packs of abandoned dogs which roam around the deserted suburb. Spheeris depicts the kids with deep affection and empathy.

*

in Roberto Faenza’s Cop Killer (aka Corrupt, 1983)

Code Red

Code Red is another company specializing in exploitation and genre movies.

Almost Human (Umberto Lenzi, 1974): Umberto Lenzi’s best feature is one of the gems of the poliziotteschi, with Tomas Milian chilling as the nihilistic sociopath Giulio Sacchi.

Copkiller (Roberto Faenza, 1983): I saw Roberto Faenza’s Copkiller when it had a brief theatrical release in the early ’80s and it stuck with me for decades; it had an odd, distinctive ambiance which I realized in retrospect derived from being an American-set movie made by an Italian director. I occasionally checked to see if it had been released on home video and finally discovered it this year, under the title Corrupt on the packaging and Order of Death on the actual print! It’s always risky to look again at something which has been lodged in your memory for decades, but it turns out to be just as interesting as I recalled. Grim and nasty, it’s about a corrupt NYC detective who imprisons someone who may be a cop killer and who could possibly expose the detective’s own crimes. Harvey Keitel is his usual intense self, but what really makes the film is John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten) holding his own against the formidable Keitel in his dramatic debut as the creepy maybe-killer.

*

in Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die (2019)

Universal

Major companies continue to release recent titles while relegating their back catalogues to smaller labels. For some reason, several of this year’s favourites came from Universal.

The Dead Don’t Die (Jim Jarmusch, 2019): Jim Jarmusch’s zombie apocalypse comedy didn’t get a lot of love or respect, largely it seems because he brought his usual cool irony to a normally intense and visceral genre, but I found it charming and entertaining, with a cast fully in tune with Jarmusch’s tone.

Captive State (Rupert Wyatt, 2019): Rupert Wyatt’s alien invasion movie also got little respect, again largely because it’s a low-key treatment of a subject usually given over to big action spectacle. I liked its small-scale focus on a handful of resistance fighters whose plan for striking back only becomes clear at the end of the film.

Happy Death Day 1 & 2 (Christopher Landon, 2017/2019): This pair were a happy surprise, a comic horror variation on Groundhog Day and ’80s slasher movies, written and directed with wit and style and given life and energy by a terrific central performance from Jessica Rothe as a blithely self-centred college girl who finds herself endlessly repeating the same day which climaxes with her own murder at the hands of a killer wearing a creepy baby mask. In the sequel she discovers the reason she’s caught in the time loop.

*

Other labels

Aniara (Pella Kagerman & Hugo Kilja, 2018): Based on an epic poem by a Swedish Nobel Prize-winning author, Aniara turns out to be a strangely haunting science fiction movie which avoids pretty much every cliche of the genre. With Earth dying from ecological disaster, large numbers of people are being moved to Mars on city-sized spaceships (reminiscent of the ship in Wall-E). When one ship is struck by debris and loses its engines, the thousands on board are doomed to drift endlessly into deep space. The film follows their adaptation and despair through decades of psychological stress and social decay. (Magnet)

The Power (Byron Haskin, 1968): I waited five decades to see the final feature of Byron Haskin (and penultimate feature produced by George Pal) and it turned out to be an interesting paranoid sci-fi thriller which prefigured the great paranoid thrillers of the ’70s. A little staid and old fashioned compared to that year’s big genre competition – 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes – it still deserves to be better known than it is. (Sinister Film, Italian DVD)

Death Laid an Egg (Giulio Questi, 1968): One of the oddest early gialli, largely because of its setting on an experimental chicken farm, Questi’s thriller of marital dysfunction and murder has a striking modernist visual style reminiscent of Elio Petri and Luigi Bazzoni. (Nucleus Films)

in S. Craig Zahler’s Dragged Across Concrete (2018)

Dragged Across Concrete (S. Craig Zahler, 2018): With a leisurely pace and self-conscious style, Zahler’s thriller about a pair of cops seduced by what looks like an easy score when they stumble on a gang’s plans for a big bank robbery, turns into a long, fatalistic descent into hopelessness and violence. Zahler lets the narrative breathe as he gives his characters plenty of room to grow. Hypnotic. (VVS Films)

Girl With All the Gifts (Colm McCarthy, 2016): Adapted from a young adult novel, this low-key zombie apocalypse story centres on an engaging zombie child who struggles with the tension between her flesh-eating urges and her innate humanity. (Elevation Pictures)

You Might Be the Killer (Brett Simmons, 2018): Like the Happy Death Day films, this is a movie which might have sunk under its own genre self-awareness if not for the wit with which it was written and directed. Joss Whedon proteges Fran Kranz and Alyson Hannigan are friends linked by cellphone as Kranz tries to survive ’80s style slaughter at a summer camp by calling Hannigan where she works at a video store, getting moment-by-moment advice on how to deal with the masked killer who, as the title points out, may well be Kranz himself. (Screen Media Films)

Dead Ant (Ron Carlson, 2017): Yet more self-aware genre play as a washed up glam band driving to Coachella in search of a comeback run across giant ants in the desert. Dumb, funny, and really entertaining if you’re in the right mood. There must have been something in the air in 2017, because this wasn’t the only ’50s throwback giant ant movie that year; but Marko Makilaakso’s It Came from the Desert isn’t nearly as entertaining, probably because its characters are annoying, while Dead Ant’s are likeable and engaging. (Cinedigm)

*

On-Line/Download

While I need disks to fully satisfy my craving, not all movies turn up on tangible media. Some nonetheless do show up on-line in copies of varying watchability, either streaming or available for download (of dubious legality). I know we’re all supposed to respect intellectual property rights, but when rights-holders can’t be bothered to make their property available (or as is often the case, rights have lapsed or holders are simply unknown), should I deprive myself of experiencing a movie I’ve long wanted to see?

Brotherhood of the Bell (Paul Wendkos, 1970): Paul Wendkos’ stylish made-for-television paranoid thriller was worth the almost five decade wait before I found a copy on-line. Like The Power, it was ahead of its time, presaging the great paranoid thrillers of the ’70s with the story of a man who finds his life being destroyed by a secret society he didn’t realize he owed his success to.

Idaho Transfer (Peter Fonda, 1973): Peter Fonda’s second outing as a director is a no-budget sci-fi movie which uses existing locations in creative ways to depict a project which intends to send people into the future to bypass a world-ending ecological catastrophe. Laconic, melancholy, and visually arresting, it’s another obscurity which deserves rediscovery and a proper release.

Unter den Brucken (Helmut Kautner, 1944): Made under the Nazis, and banned until after the war, Kautner’s three-way romance about a pair of bargemen and the unhappy woman they both fall in love with makes no reference to the war (the reason for its being banned), existing in an aura of peace where emotions and relationships are the most significant concerns of the characters. In story and visual style, reminiscent of Jean Vigo’s 1934 masterpiece of poetic realism L’Atalante.

Le Orme (Luigi Bazzoni, 1975): The third and most experimental of Bazzoni’s gialli connects an amnesiac woman’s search for her own identity and lost experience with her memories of a frightening sci-fi movie she saw as a child in which a cruel experiment deliberately strands an astronaut on the moon to study his psychological reactions to loneliness and impending death. Haunting and enigmatic.

Comments