Catching up

Minor confession: I’m not much given to self-reflection. I started this blog back in October 2010 with no particular plan. My friend Steve, who built my website – designed at the time to promote my work as a film editor (now mostly a thing of the past) and to showcase my writings about David Lynch – had told me that a viable site needs to show regular activity, so making regular blog posts would help with traffic. Since the main focus of the site was film-related, it seemed logical to jot down my thoughts on what I was watching. A purely functional act evolved into a habit which over the years has developed into a compulsion. I can’t stop writing. And here I am, some 650 posts and a million words later still at it, but without ever really having stepped back to wonder just what it is I might be getting at.

That is, there’s no overriding thesis propping up my writing, no grand view of the history, psychology and philosophy of cinema being gradually formulated piece by piece. The only thing holding it together, perhaps, is an expression of a life-long love of watching movies – any movies. But the act of writing the blog has itself generated odd unexpected pressures. I feel the weight of so many unwatched masterpieces while I spend my time watching trashy entertainment (the other day I binged all three Tomb Raider movies simply because I came across discount copies at a couple of local stores). It’s not because I’ve lost interest in great films, but may be because I’m intimidated by writing about them. I watch something less demanding, even if I’m not going to write about it, because if I do watch something more serious I feel I must write about it and suffer a sense of guilt if I don’t.

All of this is self-imposed, and there are times when I think that if I just stopped writing I could get back to the simple pleasure of watching movies, even the difficult and demanding ones. But the blog compulsion remains in control and I seem doomed to stay suspended between the pleasure of watching and the – well, I can’t call it pain, but rather obligation to keep the blog going.

Secondary to this conundrum are the specific choices of what to write about. I’m not sure myself exactly why I choose to say something about one film but not another, but given that I generally watch one or two movies every day, sometimes more, I can’t write about them all. A glance back over the past couple of months shows a pretty random collection: a couple of Albert Finney movies, two William Castle box sets, some Filipino horror, a late trilogy by Pasolini, another Hammer box set from Indicator, some ’80s slashers, four recent thoughtful sci-fi movies, the loose category of folk horror, a few mainstream American movies from the early ’70s, Wim Wenders’ globe-spanning road movie-sci-fi hybrid, a random selection of Kino Lorber releases, an “animated documentary” about a famous haunted house, and Jörg Buttgereit’s transgressive artsploitation horror films.

It’s all over the place … but there were many more from the same period that I haven’t written about, some of which may well have deserved a comment more than some I did write about. So here I’ll just acknowledge what else I was watching over the same period.

*

Blue Underground

I’m a sucker for Blue Underground’s 4K restoration releases of horror movies, many of which come with soundtrack CDs. The latest are Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979) and The House by the Cemetery (1981), and the George A. Romero/Dario Argento collaboration Two Evil Eyes (1990). The latter is far from either director’s best work, with Romero’s contribution seeming like a discarded episode from Creepshow. But Argento’s Black Cat benefits from having Harvey Keitel in the lead role. Of the Fulci films, Cemetery, although atmospheric, seemed even less coherent to me than before (and some of the dubbing, particularly the kids’ voices, is grating), but Zombie just seems to get better with time – of the three it is also the most improved visually from the restoration.

*

Severin Films

Severin is hard to beat for Eurotrash exploitation movies. The latest ones I’ve watched are Sergio Stivaletti’s Wax Mask (1997) which would’ve been Fulci’s final film, produced by Dario Argento, if Fulci hadn’t died during pre-production. A fairly standard story about a mad artist killing people for his art, it has excellent design and sumptuous photography, and not surprisingly effects artist Stivaletti comes up with impressively gruesome effects. Claudio Fragasso’s Night Killer (1989) is a typically deranged horror-thriller which, like a number of his movies, was taken away from him and completed by Bruno Mattei; a woman is stalked by a monstrously disfigured tormentor. Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory (1961) offers truth in advertising if nothing else; actually, written by Ernesto Gastaldi and directed by Paolo Heusch, that turns out to be enough – it’s an atmospherically traditional Italian tale of lycanthropy. Playing with conventional tropes, Pierre B. Reinhardt’s Revenge of the Living Dead Girls (1987) is a bit reminiscent of Jean Rollin’s zombie movies, The Living Dead Girl and Grapes of Death, with industrial pollution raising the dead who then do their gruesome thing; but its big reveal lays bare an industrial espionage/sabotage plot driven by French resentment of German corporate dominance. Just Jaeckin carried his softcore aesthetic into Barbarella/Indiana Jones territory with The Perils of Gwendoline (1984), his biggest production, adapted from a French comic strip; naive Gwendoline (Tawny Kitaen) goes looking for her lost father in an area of China known as the Yik-Yak and finds a lost civilization ruled by a cruel queen. James Kelly’s The Beast in the Cellar (1970) is worlds away from that exoticism with its story of family dysfunction and murder in rural England; disguised as a horror movie, it’s actually a dark comedy of misguided good intentions in which two eccentric sisters (Beryl Reid and Flora Robson), in trying to save their brother from the war thirty years ago, managed to turn him into an insane killer.

*

Shout! Factory

Some satisfaction mixed with disappointment from new Shout! Factory Collector’s Editions. Chuck Russell’s The Blob (1988) remains one of the great remakes of a ’50s favourite, balancing humour and horror with skill. And John Badham’s Dracula (1979) remains the best of the tragically romantic vampire movies. But looking again at an old favourite, Richard Franklin’s slow-burn thriller Road Games (1981), I had a hard time sitting through it – maybe I was just in the wrong mood, but I found Stacey Keach’s truck driver so irritating this time that he got in the way of everything that Franklin was otherwise doing so well. A movie I hadn’t previously seen also disappointed, largely because it was directed by someone who had made two of my favourite low-budget horror movies – Raw Meat aka Death Line (1972) and Dead & Buried (1981); Gary Sherman’s third feature, Vice Squad (1982), is a generic ’80s street thriller, with a cop callously using a hooker (with a heart of gold, naturally) as bait to catch a psycho pimp. Wings Hauser as the pimp is the highlight of an otherwise pretty characterless movie.

*

Arrow Video

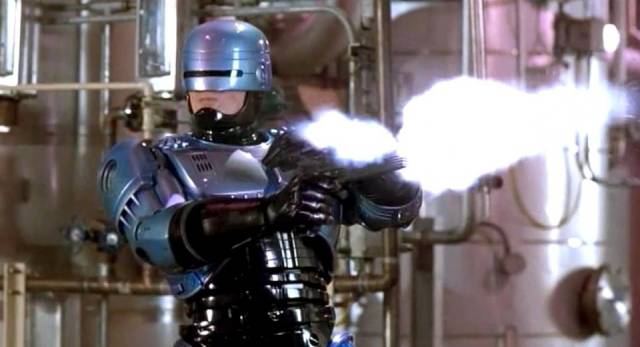

Dipping into my huge Arrow backlog, I watched Lamberto Bava’s Demons 2 (1986), which isn’t as good as his Demons (1985), largely because it’s not as tightly focused; in the first film, an audience is trapped in a movie theatre showing a cursed film, but here a high rise apartment block is overrun by monsters set free by a movie a number of tenants are watching on TV. It plays like a retread of David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and frankly I think I’d rather have been watching the movie we get glimpses of on TV, which looks more original and entertaining. I also watched the Limited Edition 4K restoration of Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987), which like Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers (1997) just seems to keep getting better with age, and looks terrific in this new edition.

*

Third Window Films

I’ve already mentioned Third Window’s release of Sion Sono’s The Whispering Star (2015); the following year he made the very different Antiporno (2016), which was essentially commissioned by Nikkatsu to relaunch their highly successful “pink film” genre from the 1970s and ’80s. Not surprisingly, Sion Sono took the opportunity to deconstruct the genre and the power dynamics embedded in softcore porno narratives; beginning with a rather theatrical sado-masochistic scene between a powerful actress and her submissive assistant, everything shifts when he pulls back to reveal both the crew filming it and the reverse dynamics in the relationship between the two actresses. Adding layers to conventional elements, the film problematizes its genre in ways which replace the superficial pleasures of soft porno with the deeper pleasures of exploring cinematic form and the relationship between reality and performance. Eiji Uchida’s Greatful Dead (2013) also plays with familiar elements in unexpected and increasingly disturbing ways; an alienated young woman becomes obsessed with what she calls “solitarians”, people like herself who have achieved a kind of authenticity from loneliness. She becomes particularly interested in an old man she spies on – and takes drastic action when he seems to “lose” his loneliness to a couple of evangelical Christians who begin to visit him. This comedy turns dark and violent, blending humour with a bleak depiction of a society which is losing the power to foster connections among its members.

*

Warner Brothers

The Witches (1990) is the most unexpected movie Nicolas Roeg ever made: based on a Roald Dahl book and produced by Jim Henson, it’s a kids’ film almost guaranteed to disturb young children. Eight-year-old Luke lives with his Norwegian grandmother after his parents die in an accident and, while on holiday on the English coast, all her tales of child-killing witches pay off because there’s a witches’ convention at the hotel. Despite being turned into a mouse, Luke has to defeat the Grand High Witch’s plan to kill all the children in England by turning her own magic against her. The mice are cute, the script witty, and the storytelling lively despite the aura of danger and death that hangs over Dahl’s tale. I hadn’t seen Joe Dante’s Innerspace (1987) since its theatrical release and it was pretty much what I remembered. Like most of Dante’s movies, it’s obsessively referential, rooted in the director’s history of watching movies rather than connecting to the real world – here, he calls up Richard Fleischer’s Fantastic Voyage (1966) and fills the movie with familiar faces from ’50s genre cinema. Full of sight gags and slapstick, Innerspace goes on too long and its characters’ development is a matter of form rather than authentic drama … but it’s nonetheless fairly entertaining. Which is more than I can say for Todd Phillips’ Joker (2019), one of the most popular and critically lauded movies of the past year. Like James Mangold’s Logan (2017), Joker has pretensions to transforming comic book into high drama, like some kind of classical tragedy. It’s grim and joyless – and far too much a retread of Martin Scorsese’s greatest film, The King of Comedy (1982), for its own good. An origin story, it proposes that the Joker began as a sad clown, living with his overbearing mother, talentless and the butt of humiliating jokes, ignored or rejected by women, who finally snaps and begins taking revenge against society. He becomes an (anonymous) hero to the underclass, his nihilism inspiring an almost revolutionary fervour. What might have been akin to the bleak satire of The King of Comedy and Taxi Driver is constantly dragged down by all the references to the Batman universe – he’s Bruce Wayne’s illegitimate older brother who eventually kills their father, thus creating his own double and nemesis, the Batman himself. It’s an ugly movie that rubs the audience’s face in embarrassment and humiliation until those watching are ready to accept and revel in nihilistic violence.

*

Criterion

I’ve long had a puzzling habit of disagreeing with critics and audiences about all manner of movies – loving at first sight such films as Leo Garen’s Hex (1973), George Roy Hill’s The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce (1985), W.D. Richter’s Buckeroo Banzai (1984), many of which eventually gained acceptance over time. I felt the same about David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), booed at Cannes, panned by critics, largely hated by Twin Peaks fans … I thought it was one of Lynch’s best films when I first saw it, not only because of its skewed humour and narrative invention, but especially because it contained his finest female character up to that time. Laura Palmer is still one of his richest inventions, and Cheryl Lee’s performance is one of the best in all of Lynch’s work. If the film is less expansive in its depiction of the TP universe than the television show, what it does convey is a world which twists and contorts in resonance with the emotional and psychological pain of one abused girl … the narrative world resonates with empathy for Laura’s suffering, making the film one of Lynch’s richest emotionally.

*

Massacre Video

I’d never come across this company before I picked up their double-feature disk of a couple of cheap ’80s exploitation movies at a local store. I guess I was just in the mood – plus one of the movies was by David DeCoteau, who for a while back in the ’90s located to Winnipeg to make really cheap direct-to-video movies that some people I knew worked on. I’m actually more familiar with DeCoteau from Trailers from Hell and various disk commentaries. His movie American Rampage (1989) is a standard cops against drug dealers thing featuring a determined female cop whose recklessness keeps getting her partners killed. There are shootouts and chases and it constantly feels as if it’s going to drift into softcore and forget the action storyline. It is at least a bit more coherent than Eames Demetrios’ Danger USA aka Mind Trap (also 1989), which has something to do with a scientist discovering a way to return from the dead. When foreign agents kill her family, the scientist’s daughter races to uncover the location of the device before they find it. The concept and plot remain very vague, but unlike Rampage it does have a couple of “big names” in the cast – Lyle Waggoner and Dan Haggerty.

*

Scorpion Releasing

Lucio Fulci’s The Psychic (1977) was a transitional film, the tail end of his giallo period and the rather subdued start of the horror years that made him an international success. One of his most low-key movies, it begins with a wealthy wife having visions of a murder which become more unsettling when she discovers that a room in her husband’s closed-up family estate matches what she’s seen. The visions lead to the discovery of a skeleton sealed in a wall, but there are puzzling discrepancies between what she’s seen and what’s been found. It almost costs her her life before she realizes that the vision had conflated events from the past and the future – she’d seen a murder which had already happened as well as her own fate.

To be continued…

Comments