Ghostly excess

in Ashley Thorpe’s Borley Rectory (2017)

At what point, if any, does an obsessive attention to technique and visual aesthetics become an obstacle to meaning? Can breathtaking style become somehow anti-cinematic? The question arises after watching Ashley Thorpe’s Borley Rectory (2017), an “animated documentary” about the legendary “most haunted house in England”. The visuals in this film are hypnotic, the magic of computer graphics managing to blend a sense of photorealism with a phantasmagorical imaginary evocation of the supernatural.

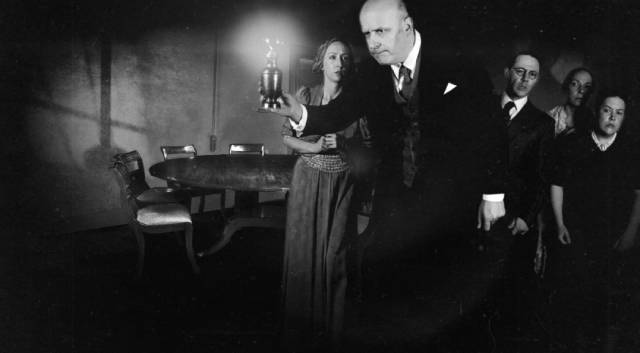

In telling the story of the Rectory, Thorpe shot actors on a green-screen stage and then spent two years painstakingly creating layered, atmospheric settings around them, frequently using actual photographs as the basis of digitally rendered rooms and exteriors. Using Adobe Aftereffects, he distressed the crisp hi-def material shot with a Red camera, adding flickering, variable exposures, ever-present dust motes constantly floating in beams of light, grain and a hint of print damage. The cumulative effect obviously references silent and early sound cinema – suggesting that the film is a record made back in the early decades of the 20th Century – but it also evokes the intense, disturbing interior landscapes of Jan Svankmajer and the Brothers Quay, and even echoes the creation of a synthetic cinematic past which has long been the project of Winnipeg’s own Guy Maddin.

But given the film’s subject, perhaps most significantly it recreates in motion the effects of spirit photography, with indistinct figures and shadows lurking at the edges of the frame and wisps of ectoplasm swirling smokily through the rooms, stairways, halls and gardens of the Rectory. Altogether, there is so much visual detail, so many layers revealing and obscuring that detail, that the viewer is both thoroughly absorbed in the imaginary space and continually distracted from the narrative content.

That content is supplied by voice over narration spoken by Julian Sands, on-screen text cards, and brief bits of dialogue from the characters who occupy the house over its eighty-odd years (built in the 1860s and torn down in the 1940s after being gutted by fire). These characters are a series of Clergymen, their wives and children, all of whom are said to have experienced unearthly manifestations. The Rectory gained its reputation because of the sheer volume of reports – a nun said to have been bricked up alive in Medieval times, a phantom carriage, messages scrawled on walls, and various other figures which appeared repeatedly over the decades.

This history eventually attracted the tabloid press in the person of Daily Mirror reporter V.C. Wall (Reece Shearsmith), whose reports in turn drew the attention of Harry Price (film historian Jonathan Rigby), a famous investigator of psychical phenomena. In the ’20s, Price and Wall set about a methodical investigation of the house (this will seem quite familiar to viewers who know Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and Robert Wise’s adaptation The Haunting [1963], and Richard Matheson’s Hell House, filmed as The Legend of Hell House by John Hough [1973], both of which were modelled in part on Borley Rectory), bringing in recording devices and eventually recruiting a team of volunteers to live for a time in the house and make notes of everything they saw and heard.

Thorpe recreates seances, reveals clues to the hauntings through spirit writing, and fills the frame with ghostly manifestations. But while we get glimpses of the people who lived for a while in the Rectory, the technique never really allows us to get much of a sense of how these people actually experienced the supposed hauntings and the impact those experiences had on them. Late in life, Marianne Foyster (Annabel Bates) apparently claimed that she had faked it all during her residence as the frustrated wife of the much older Reverend Foyster (Steve Furst), but what of all the other people who preceded and followed her?

Watching Borley Rectory, I was enchanted by Thorpe’s eccentric and single-minded obsession with creating the imagery by hand, as it were, but I was ultimately left with a degree of dissatisfaction; perhaps a more conventional documentary might have dug deeper into the psychological connections between these characters’ need for experiences “proving” the reality of survival after death and the ways in which their projections were eventually latched onto by the larger society which became fascinated by such a random collection of spooks. As it is, the film seems to swallow itself, consumed by the intoxicating task of creating these haunting images – images whose elaborateness produces a kind of distant admiration rather than full engagement.

That distance is reinforced by the performances of a talented cast, which perpetually tip towards caricature, amplifying the imagery’s suggestion of pastiche.

Although I was born just thirty miles from where the Rectory had stood, and where it had been torn down only ten years before I arrived, I was only vaguely aware of its existence. Thorpe’s film offers a tantalizing glimpse of this piece of local history, but I can’t say that it has given me a clear idea of that history or the public response to those contemporary accounts in the ’20s and ’30s. The disk itself, though – a Blu-ray from Nucleus Films – provides a great deal of information about the making of the film and also fills in some of the history which didn’t make it into the finished work. In fact, while the film is just 73 minutes long, the disk is packed with six hours of extras plus two commentaries.

The making-of alone runs half an hour longer than the feature, providing a detailed account of the effort Thorpe put in – an account further elaborated in the commentary by Thorpe in conversation with Kevin Lyons. (I didn’t listen to the second commentary from Johnny Mains, which apparently digs into the history of the Rectory and its various residents, and the impact it has had on the horror genre; I just couldn’t focus on Mains’ dry delivery.) There are no less than three festival Q&As, totalling almost 70 minutes – I don’t really have the patience for Q&As, so I only watched a couple of minutes of each.

More interesting are a half-hour on a series of copiously illustrated books from the ’70s aimed at kids, which deal with strange phenomena – Borley Rectory figured prominently – which inspired many of the people involved in the production of Thorpe’s film. There’s also an interesting conversation between Thorpe and writer Stephen Volk, who scripted the great BBC “reality show” Ghostwatch (1992), the series Afterlife (2005-06) and the feature The Awakening (2011), all of which explore the psychological effects on people who experience the supernatural. (He also wrote Gothic [1986] for Ken Russell and The Guardian [1990] for William Friedkin.)

There’s a quirky piece about Thorpe’s cabinet-maker father creating a Borley Rectory-themed Ouija board, another about Kevin Double creating a 3D model of the Rectory from original plans and photographs, which was then used by Thorpe to recreate in detail the long-gone house. Among a few other odds and ends, there are three animated shorts in which Thorpe uses rotoscoping to blend live action performances with drawn backgrounds to relate historical and contemporary folkloric incidents – a technique which he expanded on with the feature.

All of this becomes a bit overwhelming – like the film itself. Even for someone like me who appreciates excess, it was a bit too much to absorb. But despite my ambivalence, I’m sure I’ll be watching Borley Rectory again, and even this early in the year it’s hard to imagine this release is going to be topped for sheer eccentricity.

Comments