Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968): Criterion Blu-ray review

You might say that Pier Paolo Pasolini “contained multitudes”. A poet, journalist, novelist, critic and filmmaker (among other things), he was also a Communist, a Catholic and a homosexual – the multiplicity of his parts generating works both complex and confusing, their meanings often hard to pin down. His filmmaking went through a number of stages, all of them deliberately provocative, resulting in awards and condemnation and even court cases and bans in Italy. In his early work, drawing on the legacy of Neorealism, his sympathies for the underclass and critique of social and economic injustice were clear; in his contribution to the omnibus Ro.Go.Pa.G (1963), his critique of the power of Capitalism was blended with religious themes. The following year, he depicted the life of Christ in realistic terms from a Marxist perspective in The Gospel According to St. Matthew, and by 1966 an overt allegorical element surfaced in Hawks and Sparrows. He would eventually retreat from the messiness of the contemporary world into classical subjects (Oedipus Rex and Medea) and the colourful pre-modern tableaux of the Trilogy of Life, culminating in the disgust and despair of his final film, Salo, which was released just after his brutal murder in November 1975 on the outskirts of Rome.

This turn to the past (a literary, mythical past more than an objectively historical one) followed Pasolini’s most overt attacks in the late 1960s on the bourgeois Italian society he despised. Interestingly, these attacks are presented in explicitly allegorical terms, their critiques at times opaque and contradictory. Porcile (1969) is as despairing as Salo and seems in itself to have precipitated Pasolini’s turn to the past, while Teorema (1968), though also despairing, is so layered and complex that it opens itself to multiple interpretations.

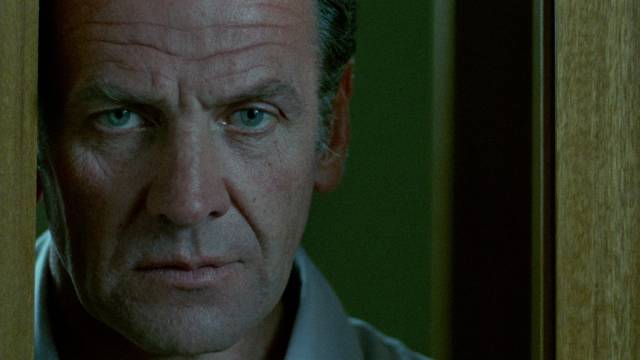

The film falls into two distinct halves. In the first, we are introduced to a wealthy bourgeois family in Milan – industrialist father Paolo (Massimo Girotti), elegant mother Lucia (Silvana Mangano), son Pietro (Andres Jose Cruz Soublette), daughter Odette (Anne Wiazemsky), and maid Emilia (Laura Betti). They live in an opulent mansion, the kids go to school, have girlfriend and boyfriend, and all of them take their privileged position for granted. Pasolini sees the family as devoid of self-awareness, their privilege insulating them from any need to think about the meaning of their place in a world of social and economic inequality. He also sees this stasis as rooted in repression; any kind of passion would threaten their stability,

And so, he introduces a disruptive force. At dinner one day, Paolo receives an unsigned telegram which says simply “arriving tomorrow”. At a party, apparently the next day, we glimpse in the background the arrival of a figure dressed in white. A friend asks Odette who this is, and she replies simply “a boy” as she looks at him with interest. Lucia also sees him and gives him an appraising look.

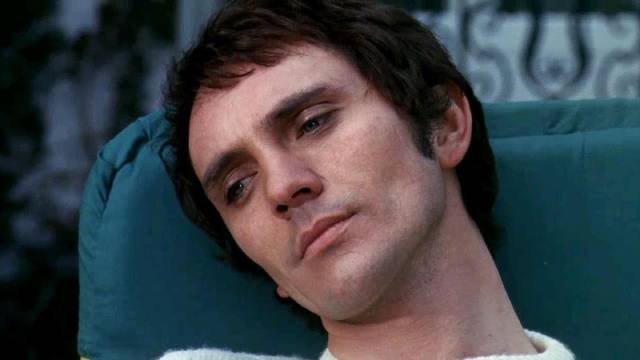

This “boy” is known only as The Visitor (Terence Stamp); no one seems to question his identity nor his purpose. But he quickly insinuates himself into the family’s life, seducing them all one by one, starting with the maid, then Pietro and so on, working his way up to Paolo. Actually, “seduction” is not entirely accurate. The Visitor is a passive character, generally seen immobile until someone prods him … his clear blue eyes remain quite inexpressive, unless they reveal a subtle air of amusement, while he seems to radiate some force which stirs desire in all who see him. Each person who succumbs to him is actually doing all the work – his presence awakens something already inside them, that repressed sexual energy which must be kept down if order is to be maintained.

Having brought this dangerous desire to the surface, The Visitor receives a telegram at dinner one day and announces that he has been called away. After his departure, the members of the household find themselves cast adrift. Each tries to cope with his absence in his or her own way, but there’s no clear way to fill the emptiness they now feel.

Emilia packs her bags and leaves, going back to the small village she came from. Odette, perhaps seeing no path to self-realization in this bourgeois society, retreats into catatonia. Pietro leaves home and takes up painting, experimenting with various styles, none of which are capable of expressing what he now feels. Lucia takes to cruising the outskirts of the city in her car, picking up anonymous young men for casual sex, as if trying to find a replacement for The Visitor. And Paolo decides that he must divest himself of the property which has thus far supplied his sense of identity, giving his factory away to the workers.

The consequences of each person’s strategy are varied and drastic, yet none seems capable of resolving the feelings of desire and emptiness left by The Visitor’s departure. Odette is lost, Pietro is trapped by creative urges his talent can’t fulfill, Lucia is filled with self-disgust which leads her to retreat into the supposed sanctuary of a small country church, and Paolo ends up wandering naked in a bleak, inhospitable landscape – the desert of volcanic ash on the slopes of Mt. Etna (to which Pasolini would return the next year for Porcile). The implication is that these complacent bourgeois are incapable of finding a meaningful existence rooted in their own inner resources, separate from the life they live through material possessions.

The exception to this bleak vision is Emilia, perhaps not surprising given Pasolini’s empathy for the underclass. This peasant woman, given a vision of something transcendent through her encounter with The Visitor, becomes an ascetic figure in her village, sitting for what may be years on a bench outside a decaying building, subsisting on boiled nettles brought to her by children, curing afflictions with nothing more than a sign of the Cross, and eventually rising up to levitate in the sky above the village, arms out like the crucified Christ, as the villagers kneel beneath her in adoration.

Here, although Paolo giving autonomy to his workers points towards an economic alternative, Pasolini’s critique of an untenable political system finds its only positive answer in his religious convictions. And yet the film is framed by Paolo’s response to The Visitor; it opens with a documentary-like prologue in which a television reporter interviews workers about the implications of being given ownership of the factory (we only realize towards the end that this is Paolo’s factory in a kind of flash-forward) – does this mean the end of the bourgeoisie because the working class is now being absorbed into it? – and it ends with Paolo, emblem of the economic system, stripped of everything and wandering naked through a lifeless wilderness, screaming in despair.

Pasolini appears to be unable to see a viable political solution to the dead end of Capitalism. Emilia’s transformation points back towards the pre-modern world which would consume Pasolini’s filmmaking for the next half decade, which he eventually concluded was another dead end, leaving him nowhere to go except the complete rejection in Salo of what humanity has done to itself. As for The Visitor, he has been interpreted variously as a Christ figure or the Devil; Pasolini himself suggested that he is God, or at least a representative of God (though not Christ).

Despite its bleakness, Teorema is one of Pasolini’s most entertaining films; but it got a mixed reception when it was released in 1968. It won the International Catholic Critics award at the Venice Film Festival, but was condemned by the Catholic Church – though not, apparently, for its radical political ideas or its possibly sacrilegious view of divinity, but rather for its sexuality. The film is unambiguously pan-sexual, the men and women of the household equally attracted to The Visitor, whose power over them is obviously rooted in his sexuality (Pasolini repeatedly returns to shots of Stamp’s crotch in tight trousers as those looking at him slip off their inhibitions). Some critics even viewed the film as an attempt by Pasolini to deal with his own conflicted homosexuality, though there is obviously far more going on than such a singly focused critique can encompass.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray has been mastered from a new 4K restoration and the image is bright and detailed, with prominent grain giving it a rich film-like texture. The disk offers the option of the Italian soundtrack or the English dub. Since the latter includes most of the performers (including Stamp) speaking their own lines, for me it’s the preferable choice (it’s obvious that the actors were speaking English on-set, so this track mostly appears to be in sync).

The supplements

There’s a commentary from film scholar Robert S.C. Gordon recorded in 2007, which covers the production, the ambiguities of the film and its place in Pasolini’s career.

There’s a brief clip from French television (2:37) in which Pasolini is cagey about the film’s meaning; an engaging interview with Stamp from 2007 in which he talks about his career and the experience of working with Pasolini (33:13); and an interview with John David Rhodes, author of a book about Pasolini, in which he digs into the ways in which the film avoids easy interpretation (16:41).

The booklet includes a typically erudite essay from James Quandt.

Comments