Three Fantastic Journeys by Karel Zeman:

Criterion Blu-ray review

Children, new to the world, are imbued with a sense of wonder. They encounter each fresh experience with an open curiosity, eager to grasp – and eventually understand – the world around them. One of the pleasures of cinema since its invention is its ability to restore us to that state. Paradoxically, the now ubiquitous effects of digital technology are threatening to change this – when we know so well how all this synthetic imagery is created, we lose the ability to wonder. We sit passively and look at impossible images with a sense of their over-familiarity, struggling to stave off boredom.

For those not yet entirely jaded, pre-digital effects – hand-made, as it were, from physical objects captured on film with actual light – may still evoke a sense of wonder even as they lack the supposed perfection of CGI … in fact, partly because they do show signs of their creators’ activity. The slight unnaturalness of stop-motion movement is not a flaw, but rather visible proof that an artist has miraculously imbued inanimate objects with life and expression. One only has to compare Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s King Kong (1933) with Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake to get a visceral sense of this difference; one engages its audience with genuine emotion while the other is nothing more than a technical display of empty spectacle.

While the complex demands of creating fantastic illusions with a combination of actual physical objects and photochemical techniques were the standard for cinema’s first nine decades, from Melies through Lang and Harryhausen to Star Wars and Blade Runner and The Thing, few filmmakers lifted the artisanal possibilities of film to the level of high art like Karel Zeman, the self-taught Czech master who combined 19th Century fantasy with the expressive possibilities of film in a series of features from the mid 1950s to the late ’70s.

Zeman is a Czech national treasure (there’s a museum devoted to him and his works in Prague, where workshops teach children his techniques), and in the late ’50s and early ’60s he was the country’s biggest international success, winning festival awards and gaining wide distribution. And yet, although he was an acknowledged influence on filmmakers like Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton, his films have not been widely available in the English-speaking world for decades. For myself, although I knew of his work, I didn’t actually see any of it until the Karel Zeman Museum began releasing restored versions on English-friendly DVDs in 2012. (These had to be ordered directly from the Museum, at ridiculously low prices.)

in Karel Zeman’s version of Munchausen (1962)

Now Criterion have released a wonderful set of three key features. (I know I can’t take credit, but in a 2015 review of two of the Museum’s releases, I did suggest that Criterion form a partnership with them to release his films in North America.) The set includes Zeman’s best known film, Invention For Destruction aka The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), along with Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) and Baron Prasil aka The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962).

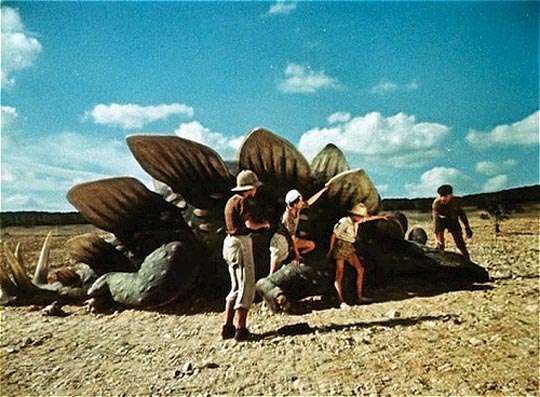

Stylistically, Journey is the most conventional, if you can validly use that term – it combines live action with puppets and stop-motion in ways familiar from the work of people like Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen, using mattes and split-screen to create virtually seamless images of a group of four boys as they travel backwards through geological eras in which they encounter a variety of now-extinct animals – sabre-toothed tigers, woolly mammoths, and dinosaurs – until they reach the shore of the primordial ocean where they finally discover a living trilobite to match the fossil which inspired their journey.

While the film is quite open about its educational purpose, Zeman delivers his lesson in the form of an exciting children’s adventure, with the four boys having to work together to survive genuine dangers as they explore the evolutionary history of our planet. The numerous effects shots keep it visually exciting and frequently evoke genuine awe with audacious design and unexpected detail. When the boys witness a death-struggle between a Tyrannosaurus and a Stegosaurus, Zeman stages it in the twilight of a blazingly colourful sunset, making it the most spectacular such scene in any film.

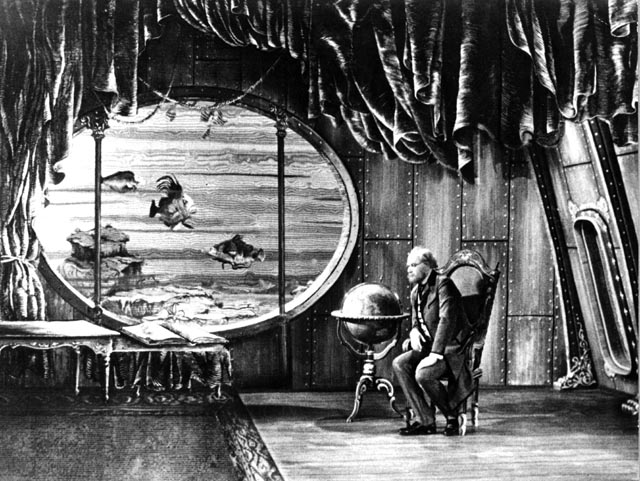

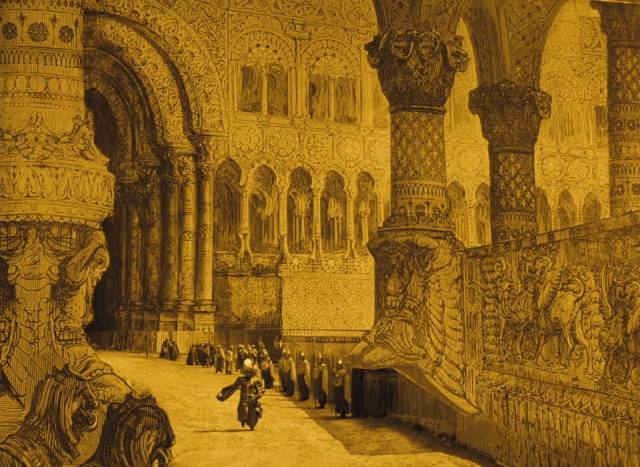

With his next film, Zeman completely departed from the effort to convey this scientific adventure with a degree of realism; the unique Invention For Destruction (1958) uses for its model the engravings which illustrated 19th Century editions of Jules Verne’s novels. Largely based on Verne’s 1896 novel Facing the Flag, and incorporating elements from other works (it’s similar to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in many ways), it tells of a scientist kidnapped by a Count who has built a base inside an island volcano; the scientist is working on an ultimate power source, unconcerned about what use it will be put to, and naturally the Count is determined to use it as a weapon to dominate the world.

While the narrative seems quite familiar, Zeman transforms it into one of the true wonders of cinema, embedding his actors into dazzling animated engravings – sets, objects, even clothing are rendered with the cross-hatching of the illustrations which inspired the film. Every image evokes the memory of a childhood wonder inspired by reading these old adventure stories, with that wonder shot through with subtle comic detail – the stop-motion of animated divers ransacking a ship sunk by the Count’s submarine includes underwater bicycles complete with little bells; two divers draw swords and duel over a treasure chest…

Zeman’s imagery here is a combination of technical sophistication and the sense of unfettered, innocent invention of Melies, surprising viewers by taking them back to the novelty and power of the very first moving images.

Zeman’s next feature, Baron Prasil (1962), was loosely adapted from Rudolph Erich Raspe’s 1785 book about a boastful nobleman who tells outrageously exaggerated stories of his exploits (based on a real nobleman named Baron Munchausen). In Zeman’s telling, the Baron is not a self-aggrandizing buffoon; his adventures are taken at face value. The film begins with a modern astronaut landing on the moon, who, after discovering Verne’s rocket, finds several men in period costume, including Cyrano. These men assume from the astronaut’s strange costume that he must be a Moonman and when the Baron arrives he decides to introduce the Moonman to Earth (refusing to believe that the astronaut is a native).

Flying to Earth in a ship pulled by winged horses, they arrive at the Sultan’s palace in 18th Century Turkey where Tonik, the astronaut, rescues an imprisoned princess. Many adventures ensue – sea battles, being swallowed by a whale, the Baron’s famous ride on a cannonball … all depicted in an elaborate mixture of live action and animation, here looking more like a child’s puppet theatre with layered two-dimensional cut-outs providing an illusion of depth.

What really marks Zeman as a true artist is not simply the profligacy of his invention, devising a seemingly endless series of techniques to visualize his fantasies, but more importantly the seeming effortlessness of it all. For all the remarkable detail, he doesn’t flaunt his inventiveness – it’s always there to serve his deftly satirical narratives. This too adds to the child-like wonder his films inspire, giving his audience a constant sense of delight. At no point does he appear to be doing something merely to impress; in this, his work seems enormously generous – his concern is simply to give the viewer a kind of pleasure which only cinema is capable of providing.

*

The disks

Criterion showcases these films in a three-disk set mastered from 4K restorations provided by the Karel Zeman Museum and they all look wonderful. Each disk includes a short restoration demonstration, showing how much work was involved in repairing age-related damage to the source elements, including extensive work on faded colour to restore the films’ visual vibrancy.

The three disks have been packaged in what amounts to an elaborate pop-up book housed in a slipcase which itself has a colourful cut-out illustration on the front.

The supplements

Although there are no commentaries, the plentiful extras provide a great deal of informative background material spread across the three disks. There are almost an hour’s worth of brief clips from the Museum, with interviews and archival material about Zeman and aspects of his work.

Disk one has a new featurette with filmmaker John Stevenson about Zeman’s animation techniques (12.24), plus a reconstruction of the 1960 U.S. release version of Journey to the Beginning of Time (1:23:36), which creates a new frame with four young Americans who visit the natural history museum in New York and dream the whole adventure when they all nod off in front of a dinosaur skeleton. In contrast, there’s no question in the original that the boys’ adventure is real.

Disk two has a conversation between stop-motion animators Phil Tippett and Jim Aupperle (23:29), plus the alternate U.S. opening of The Fabulous World of Jules Verne which features broadcaster Hugh Downs introducing the film and the amazing new technique of “Mysti-Mation”.

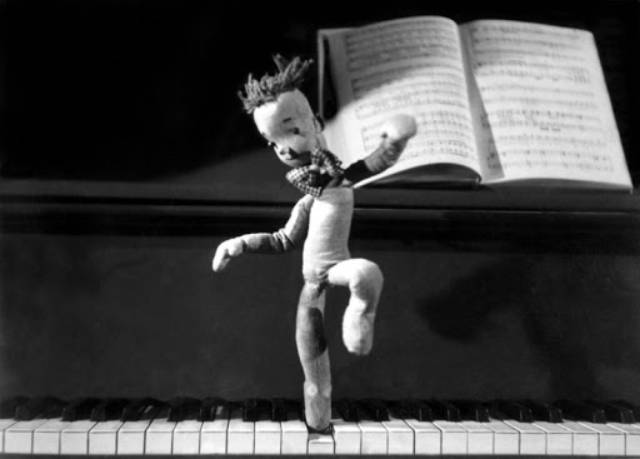

Most importantly, this disk also includes four of Zeman’s early animated shorts, beginning with A Christmas Story (1945, 10:49), which already displays a sophisticated blend of live action and stop-motion animation, while A Horseshoe for Luck (1946, 4:36) and King Lavra (1950, 29:41) are both reminiscent of the puppet animation of Jiri Trnka and George Pal. Inspiration (1949, 11.32), on the other hand, is something quite else; here Zeman created a romantic fantasy made with animated glass figurines – each frame required glass-makers to create these figurines with slightly different positions, which were then replaced frame-by-frame to give the illusion of movement. Inspiration is one of the most exquisite animated shorts I’ve ever seen.

Disk three, in addition to the short Museum clips, includes Film Adventurer: Karel Zeman (2015, 1:41:50), a feature-length documentary, also sponsored by the Museum, which manages to pack in an enormous amount of information. There are interviews with Zeman’s co-workers, his daughter Ludmila, and for perhaps unnecessary international appeal Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton. There’s also plenty of archival footage of Zeman at work, plus a compact history of Czech filmmaking from World War Two through the Communist years during which Zeman’s international success gained him support from the bureaucracy, up through the New Wave and the Soviet invasion in 1968, after which the new bureaucracy was suspicious of Zeman’s success in the West, eventually making it impossible for him to continue with the kind of films he had been making – from 1970 until the end of his career a decade later, he concentrated on drawn animation, creating the masterpieces The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1978) and The Tale of John and Mary (1980) plus a series of shorts about Sinbad.

Woven through this detailed record of his career are sections in which a group of students use Zeman’s techniques to recreate three sequences from the films in this set, illustrating the enormous amount of work and technical skill needed for just a single shot … and the great satisfaction to be gained by achieving his remarkable effects.

There’s a trailer for each film, and an enthusiastic essay by critic Michael Atkinson.

Three Fantastic Journeys by Karel Zeman will be one of this year’s essential releases … and hopefully is just the first in a series; it inspires an appetite for the rest of this remarkable artist’s work.

Comments