Trawling the Internet

In addition to all the movies I’ve been writing about in the past couple of posts, there’s yet another layer to my viewing … one perhaps less legitimate. I occasionally go trawling on the Internet looking for obscure, harder to find movies, some of which are no doubt public domain, while others are probably illicit. Some (no doubt the latter) are of very good quality – others are weak transfers from battered prints, recorded off television or taken from old VHS tapes. This aspect of my movie addiction carries a trace of nostalgia – memories of watching late night movies on small television sets, pulling the signal in with an unreliable antenna, or playing a worn out videotape rented at a corner store for a buck.

Among my recent forays into this particular film-culture cellar there are two movies I saw on TV as a kid, but haven’t seen since. I had vivid memories of fragments but not of the whole, so I was pleased to find them. (I only subsequently became aware that one of them had a legitimate Blu-ray release a year or so ago.)

Today, Doctor Blood’s Coffin (1961) is mostly of interest as an early feature directed by Canadian ex-pat Sidney J. Furie before his brief flurry of interesting movies – say, from the Cliff Richard musical The Young Ones (Furie’s fourth feature in 1961) to The Ipcress File (1965) – before a long and generally mediocre career in movies and television (his most recent movie was released in 2018). When I saw it on TV in the ’60s, though, it was the novelty of its Cornish setting that made it stick in my mind; that was an area I could recognize from family holidays, so it had a kind of personal immediacy for me.

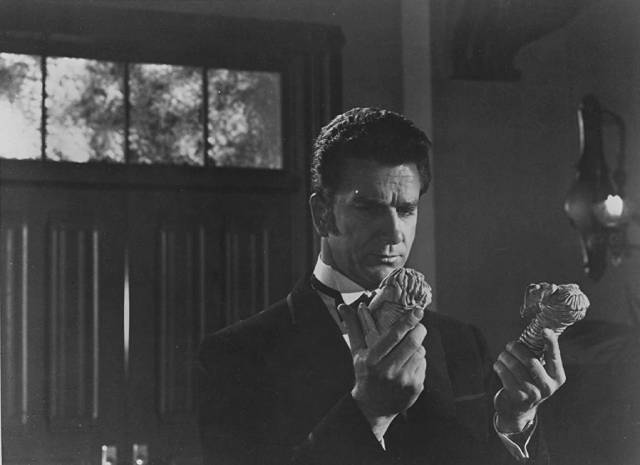

The film doesn’t stand out as a particularly notable example of British horror from the flurry of activity in the years following Hammer’s groundbreaking Gothic movies, but it’s efficiently made and has an interestingly compromised protagonist. Young Dr. Peter Blood (Kieron Moore) leaves medical school under a cloud when his mentor balks at his radical experiments into prolonging life. He returns to the village in Cornwall where his father (Ian Hunter) is the local doctor. Brash and impatient, Peter isn’t interested in his father’s kind of practice, but he is interested in his father’s nurse, Linda Parker (Hazel Court).

Meanwhile, local people have been disappearing mysteriously, a few turning up dead. Peter volunteers to perform autopsies, but it turns out he has ulterior motives. It’s soon revealed that he has been continuing his experiments in a local abandoned tin mine, playing concerned citizen by day, cooperating with the police and going on picnics with Linda, while at night he cuts out people’s hearts and keeps them alive artificially. The odd thing is, because he’s positioned as the protagonist, we can’t help rooting for him as the risk of discovery comes closer.

Another point of interest is that the story and screenplay are by pulpy director Nathan Juran (with some additional work by Beast in the Cellar’s James Kelley), best known for his Ray Harryhausen movies and some classically cheesy ’50s sci-fi (The Deadly Mantis, The Brain from Planet Arous, Attack of the 50-Foot Woman).

I’m not sure when I saw Blood of the Vampire (1958) on television, but I think it might have been my first British Gothic horror movie. It’s interesting for a number of reasons, not least in that it was written by the prolific Jimmy Sangster the same year he wrote Hammer’s Dracula – which means that in a way he was both ripping himself off and openly competing with his most important employer. It also shows how astute producers Monty Berman and Robert S. Baker were in following Hammer’s lead, although with even smaller budgets. There’s little doubt that the intention was to make people believe this was a Hammer production – an impression further reinforced in retrospect by the presence of Barbara Shelley as the heroine.

Although the sets are not as richly designed as those Bernard Robinson provided for so many Hammer productions – and the miniature landscapes and castles are more obviously small models – Monty Berman’s moody and deeply saturated colour photography echoes Jack Asher’s lush look in Dracula and Curse of Frankenstein. Perhaps because it was an independent production made to cash in on Hammer’s transgressive horrors, it seems even more overtly sadistic than its inspirations. It has a villain steeped in arrogant cruelty and there are glimpses of nastiness visible at the edge of the frame in many scenes – a tortured man tied to a frame, his skin flayed by a whip, nubile women chained in a dungeon awaiting their turn to be used in cruel experiments.

Interestingly, despite the title, there is no supernatural element. As in Doctor Blood’s Coffin, the villain is a doctor conducting experiments with blood. To that end, he has become the head of a prison for the criminally insane, pathetic hopeless characters whom nobody is likely to miss as he drains them of blood or cuts out their hearts and keeps them alive with artificial means – in fact more like Frankenstein than Dracula (and of course, Dr. F would himself take over an asylum in Hammer’s final film in their series, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell [1974]).

In the title sequence, we see Dr. Callistratus (Donald Wolfitt) staked through the heart and buried by townspeople who believe he’s a vampire because of his blood research. His faithful hunchback assistant Carl (Victor Maddern) digs him up and gets a drunken doctor to replace his damaged heart with one kept alive in a jar. We rejoin him years later at the asylum when Dr. John Pierre (Vincent Ball) arrives as a prisoner. Convicted of murder after a patient died while he was trying to save her with a blood transfusion, he expects to be released when crucial evidence is presented. What he doesn’t know is that Callistartus has deliberately buried the evidence and bribed court officials in order to enlist Pierre in his experiments.

When word is put out that Pierre died during an escape attempt, his fiancee Madeleine (Shelley) infiltrates the prison by posing as the new housekeeper. Seeing that Pierre is still alive, she manages to fill him in on the lies which have trapped him in the prison and together they work to escape … but not before things get worse.

Directed by the undistinguished Henry Cass, Blood of the Vampire is better than most quick attempts to cash in on a recent success and works well on its own terms as a thick slice of Gothic ham.

*

Those were the two I’d seen decades ago and had some memory of; the ones which follow appeal to my taste for low-budget genre movies, but are all new to me, though I had seen some of the titles mentioned in various books or magazines over the years.

Sometimes it takes a single performance to fix an actor’s image in the audience’s mind, all but erasing everything that came before. The Leslie Nielsen we know now actually sprang into being in 1980, thirty years into a prolific movie and television career in which he had most frequently played no-nonsense types like Commander Adams in Forbidden Planet (1956). But then at the age of fifty-six, Nielsen starred as Detective Frank Drebin in Police Squad! (1982), followed by the series’ offshoot trilogy of Naked Gun features, and although he did still play serious parts, his image was indelibly fixed as a clueless but deeply self-serious comic buffoon. In retrospect, a touch of comic self-awareness does reveal itself in some of those earlier overtly dramatic roles.

In Harvey Hart’s compact little B-movie Dark Intruder (1965), Nielsen plays one of those psychic investigators who were quite popular at the time – like Martin Landau in The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre (1964) and Louis Jourdan in Fear No Evil (1969), a type definitively sent up by Darren McGavin in The Night Stalker (1972). Unlike the abrasive Kolchak, who continuously butted heads with the authorities, Nielsen’s Brett Kingsford works behind-the-scenes to help the police solve a series of brutal murders in 1890 San Francisco. This low-budget one hour has the feel of a TV episode (maybe from Thriller [1960-62]), light but atmospheric, with a storyline which vaguely prefigures Basket Case (1982).

The script, though an undeniably minor effort, was the final feature work by Barre Lyndon, who had been responsible for quite a few genre classics – John Brahm’s The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945), Byron Haskin’s The War of the Worlds (1953) and Conquest of Space (1955), Terence Fisher’s The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959). Director Hart – a Canadian who moved back and forth between Canada and the U.S. over a long career, mostly in television, with an occasional feature thrown in (the most interesting being a horror-mystery called The Pyx, shot in Montreal in 1973) – is more efficient than stylish, the toned-down horror adding to that made-for-television feel.

Jaws of Satan (1981) appears to have been the sole theatrical feature by another prolific TV producer-director, Bob Claver, who made this somewhat absurd horror movie between episodes of The Facts of Life and Mork & Mindy. A small American town suddenly finds itself under attack by snakes after a giant cobra arrives on a freight train whose crew are all dead. As the bodies pile up, the mayor and business leaders downplay the threat because they’re due to open a lucrative new dog track in a couple of days (shades of Amity Island’s beaches on the 4th of July weekend). Against these vested interests is pitted dedicated doctor Maggie Sheridan (Gretchen Corbett) who calls in snake expert Dr. Paul Hendricks (Jon Korkes); at first it looks like Paul has made a wasted trip because the mayor has had the cobra’s first victim quickly cremated to hide the hideous evidence of the monster’s poisonous bite.

But not to worry – more victims turn up. It becomes clear that what they’re dealing with is no ordinary serpent because something seems to be directing and coordinating all the regular snakes in the area. The key turns out to be local priest Father Tom Farrow (Fritz Weaver), a gloomy and not very popular cleric. We learn that Father Tom is descended from an O’Farrow who worked with Saint Patrick to expell the snakes from Ireland – and in the process helped to burn a lot of Druids. Not sure where writers James Callaway and Gerry Holland got the idea that Druids were closely aligned with Satan, but in their telling the great Serpent reappears every few generations to exact revenge on O’Farrow’s descendants and now he’s come to get Father Tom.

Claver isn’t up to creating much in the way of atmosphere, but he does keep things moving – except for one truly egregious sequence. We’ve seen that Dr. Maggie is a tough, self-confident woman, willing to stand up to powerful men and put herself at risk, and yet when Paul drops her off one evening, we get a long sequence of her preparing for bed – undressing, taking a shower – all designed to build up a sense of vulnerability because she’s oblivious of the fact that she’s being stalked in the bedroom and bathroom by a rattle snake as the big cobra watches from outside. Then she gets on the bed in her nightie and sees the rattler slithering up over the foot of the bed … and this tough woman is suddenly reduced to utter helplessness.

Her most obvious option is to grab the covers and throw them over the snake before it reaches her, thus hindering it long enough to get away. But instead she cowers by the pillows watching it come closer … and picks up the phone … and calls the motel where Paul is staying, a couple of miles away … and tells him there’s a snake on her bed … and waits there cowering helplessly as he runs out of the hotel, gets in his car and drives to her place, smashing the locked door to get in, running up the stairs to the bedroom and using his snake-catcher stick to pin it down before blowing its head off with a pistol (despite having already neutralized it). Luckily, the rattler had moved so slowly that it still hadn’t reached Maggie at the head of the bed.

Then, having been rescued from her abject helplessness, Maggie collapses in hysterics, forcing Paul to give her a good hard slap. All of this would have been ridiculous in the ’40s or ’50s, but how on earth it got past a first draft in 1981 is truly baffling. Rather than generating suspense, it all but sinks what on the whole is a mildly entertaining B-movie.

The absurdity of Herbert L. Strock’s The Crawling Hand (1963) perhaps exceeds the giant snake in Jaws of Satan, but despite being generally dumb it never shoots itself in the foot like that. The space agency is having bad luck bringing astronauts back from the moon alive. After losing contact for hours with the latest, knowing that his oxygen supply has finally run out, they’re surprised when he calls in – but there’s something wrong. He’s still alive despite having nothing to breathe, and even worse he has thick black eye shadow and pleads with ground control to hit the destruct button before his capsule can land. Which they promptly do…

Meanwhile Swedish exchange student Marta (Sirry Steffen) and her boyfriend Paul (Rod Lauren) are frolicking on the beach when they come across a severed arm in the sleeve of a space suit. Marta insists they leave immediately, but after dropping her off Paul goes back to retrieve the arm. Unfortunately, it’s possessed by an alien force which takes him over. The arm and Paul go on a spree killing people while mission control scientist Steve Curen (Peter Breck) comes to town to figure out what happened to his ill-fated moon man.

Silly, cheesy and, shot in black-and-white, already looking very dated by 1963 (this was ten years after Strock’s 3D colour Gog), The Crawling Hand is entertaining drive-in grade fare which wouldn’t be out of place on a double bill with Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster (1965).

*

In contrast to such throwaway cheese, I stumbled on three interesting foreign films I knew nothing about.

Bruno Gaburro’s Ecce Homo (1968) is a stark example of the after-the-bomb genre which adheres to many of the familiar tropes but executes them with great skill. Set on a white-sand beach, it begins with a family of three – father, mother, and adolescent son – scraping by day by day, fishing and scavenging from derelict nearby buildings, while avoiding towns which are probably still contaminated with radiation. There are tensions because the wife, Anna (Irene Pappas), is still vibrantly alive while her husband Jean (Philippe Leroy) is slowly wasting away from radiation poisoning. Jean is suspicious and irritable, no longer capable of satisfying Anna sexually and finding it increasingly difficult to do the things he needs to do to maintain even a basic level of survival.

As always seems to happen in these stories, one day two men turn up – the middle-aged intellectual Quentin (Frank Wolff) and the young soldier Len (Gabriele Tinti). They’re really happy to find other survivors after travelling through deserted cities, but Jean is deeply suspicious. It doesn’t help when Quentin starts talking about the need to start repopulating the world, given that there’s only one woman and Jean himself is incapable of reproducing. Quentin eventually tries to force himself on Anna, causing a rift between him and Len. Anna is openly interested in the latter and all this sexual tension and male insecurity results in a violent downward spiral.

Is it because these movies are typically written and directed by men that they almost always revolve around competition for the only breeding female left alive? No doubt it’s natural, given that the initial premise is that we’ve pretty much obliterated ourselves, that these stories end up reducing us to our basest instincts, but it’s disturbing to think that extremity seems inevitably to reduce all behaviour to macho competition for sexual possession of a woman.

Gaburro, who co-wrote the script, directs well in what was just his second feature, getting good performances from his cast and infusing the stark setting and narrative with a genuine erotic charge (at least some of his subsequent twenty-odd features appear to border on soft core). Maybe it’s the cast and the language, but Ecce Homo gives the impression of conveying something more serious than most of the movies in this genre.

Krsto Papic’s The Rat Savior (1976) is an unsettling mix of horror and allegory. Set in a city collapsing under the pressure of economic failure – streets full of the unemployed and homeless while a demagogic mayor makes rousing speeches about better times coming – it follows an unemployed, unsuccessful writer who stumbles across a horrifying secret: rats are assuming human form under the influence of the Rat Savior, a powerful creature which appears intermittently in history to raise the rodents to a position of power. They’re killing those who oppose them and replacing others so they can take over positions of influence.

The writer becomes involved with a scientist who is working on a way of exposing and destroying the rats, falling in love with the professor’s daughter. Together they try to alert the authorities and seem to get the mayor on their side, but the rats’ infiltration is already deep and wide. Although the writer finally manages to defeat the Rat Savior, it’s at great cost and in the face of warnings that the next one will soon appear and with even greater power.

There are overt references to the rise of Fascism in the ’20s – when the rats gather for their feasts, they eat at a table in the form of a half swastika; the Savior’s minions wear long black leather coats – and the climactic warning obviously refers to the imminent coming of Hitler, but there’s an uncomfortable subtext which seems to conflict with this. The idea of swarming rats overrunning society was a favourite metaphor applied by the Nazis to the Jews, seeming to offer a more insidious reading of the power of the rats to infiltrate society and seize economic and political control.

As a horrific fantasy, The Rat Savior is atmospheric and visually inventive. As allegory, however, it’s problematic.

Marek Piestrak’s Test Pilota Pirxa (1979) is a sombre Polish sci-fi movie based on one of Stanislaw Lem’s short stories about Pilot Pirx, which generally feature the spaceman using logic and experience to solve a puzzle. In this case, Pirx (Sergei Desnitsky) is given the task of evaluating the suitability of androids as crew on spaceships. The corporations which have developed robots indistinguishable from humans are against him being given the job because an unfavourable report will bankrupt them – so before the flight, there are attempts on Pirx’s life, which rather than discouraging him just make him more determined.

During the flight to the rings of Saturn, various members of the crew meet privately with Pirx, either to declare their own humanity and cast doubt on some other crew member, or in one case to admit to being an android. Pirx doesn’t put a lot of weight on what he’s told – his job is to observe everyone and evaluate individual performance. When the ship reaches Saturn, the crew’s job is to launch a probe into a rift between the rings; it’s crucial to avoid flying the ship itself into the gap because it would almost certainly be destroyed.

However, John Calder (Zbigniew Lesien) actually accelerates the ship into the narrow rift, the increased g-force rendering everyone else virtually helpless. An android, Calder is determined to return to Earth alone to prove that only artificial crewmen can survive the rigours of space travel. Pirx and another crew member manage to foil his plan and Pirx returns to Earth with that negative report, blocking any further development of androids.

The film has the kind of basic approach common to ’50s space movies like Destination Moon and Conquest of Space, in which drama is stripped away in favour of solving technical problems – though production values and special effects are better. The cast are good in their essentially functional roles – it’s interesting to see Aleksandr Kaidanovsky mere moments before his remarkable performance as the Stalker in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film of that name; though he does well as the ship’s medical officer, he barely resembles the tortured, philosophical character he would play a few months later.

*

Test Pilota Pirx has the no-nonsense tone of most Eastern Bloc sci-fi, but a pair of British movies produced by Amicus in the ’60s plunge headlong without apology into pulp. The company which most successfully rode the coattails of Hammer occasionally strayed from their familiar line of horror anthologies and stand-alone horror movies, with some wildly mixed results – in this case a pair of adaptations released almost back-to-back in 1967, one something of a disaster, the other a routine but competent recycling of familiar story ideas.

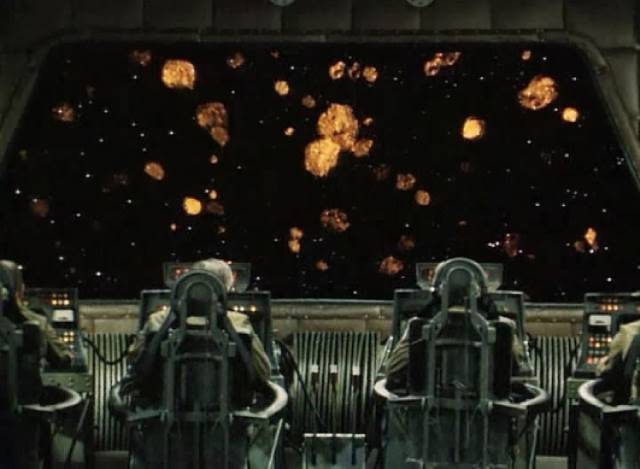

The former is The Terrornauts, directed by the undistinguished Montgomery Tully at the end of a thirty-year career. Based on Murray Leinster’s 1960 novel The Wailing Asteroid, it follows the adventures of a team searching for signs of intelligent life on other planets. They detect and respond to a signal coming from the asteroid belt and find themselves (and their research building) sucked up into a spaceship and taken to the source of the signal. There they find what appears to be an abandoned station – there’s one desiccated humanoid body and a helpful robot. Using the technology they find, they learn that the builders left the station there to protect Earth from a marauding alien civilization which is going around the universe wiping out all other intelligent forms of life.

The team must master the station’s weapons systems to destroy the incoming alien fleet before heading back to Earth (with a brief detour to an alien world whose inhabitants have been reduced to superstitious primitives).

The problem with The Terrornauts is its wildly uneven and inappropriate tone, the supposed stakes undermined by painfully unfunny comedy courtesy of British comedy icons Charles Hawtrey and Patricia Hayes as a twitchy accountant and office charlady respectively. Perhaps the most puzzling thing of all is that this was the only film writing credit of the great science fiction writer John Brunner. Hard to say whether he was responsible for the mess, or whether Tully mangled a more straightforward script. (Admittedly, it was made just as Brunner was transitioning from pulp to serious literature – the next year, he published his breakthrough novel Stand on Zanzibar.) None of this is helped by production values and model work which would have embarrassed even Doctor Who.

Not surprisingly, They Came From Beyond Space (also 1967) is at least a functional sci-fi thriller, if not particularly original, because it was directed by the competent though seldom inspired Freddie Francis. It was adapted by Amicus producer Milton Subotsky from a 1941 pulp novel by Joseph J. Millard called The Gods Hate Kansas, which with its alien takeover plot prefigured Robert A. Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters (1951), Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers (1955), and Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass II (1955).

Nine small meteors strangely land in formation in a farmer’s field and a team of scientists are sent to investigate, though top space scientist Curtis Temple (Robert Hutton) is barred from going because he has had a silver plate implanted in his skull. The team, headed by Temple’s girlfriend Lee Mason (Jennifer Jayne), are quickly taken over by alien intelligences which have used the meteors to get to Earth from the moon. They seal off the farm and begin a massive construction project with an underground installation and rocket launch pad. When Temple finally drives down to see what the heck is going on, he’s chased off by armed guards. Nonetheless, he hangs around spying on the farm and enlists the help of engineer friend Farge (Zia Mohyeddin), who figures out that the silver plate has protected Temple from alien take-over.

Together, they infiltrate the farm and rescue Lee; the three of them sneak aboard a spaceship and get to the moon where they quickly learn the history and motives of the aliens from the Master of the Moon (Michael Gough). Despite enslaving people and spreading a plague on Earth, it turns out they’re not really malevolent, just arrogant and condescending. They’re just using humans to repair their ship so they can get back to their dying planet … as Temple says, “All you had to do was ask for help,” and it all ends with a friendly handshake.

Although the ending falls pretty flat and the mid-section gets repetitive with Temple sneaking up to the farm and getting driven off over and over again, Francis keeps it moving and it does have some effective moments.

As with some of the other Amicus films that strayed from their horror staple, the inadequate budgets of this pair make them less satisfying than the anthologies, but I’m glad I finally got around to seeing them.

Comments

I don’t mind watching stuff on YouTube and the like, sometimes it’s the only place that they are available, and luckily the quality of the uploads are getting better. Often it gives me a chance to see the movie and know I won’t need to see it again. I’ve got plenty of DVDs I bought sight unseen and now I doubt I’m going to watch them again. I certainly keep way too many poor movies. Especially all those multi movie packs with random horror films. They can be miss, miss, miss all the way to the end of the set. Sadly, they aren’t worth selling because they still aren’t worth anything.

Yeah, I have some of those sets and I’ve never watched all the movies in them – I’d usually buy them because of one or two titles and as often as not the quality of those few would be so bad I’d end up unhappy with them. I’m more bothered by the accumulation of good movies I never seem to find the time to watch, partly because I spend my time looking for this obscure stuff on the Internet.

I occasionally watch full movies on YouTube if I can’t find them on other streaming services. The Sound Barrier, and No Highway in The Sky being a couple of childhood favourites that still stand up for me. If I can’t find decent quality, though, I won’t watch them.

As for movies bought and not watched… I do that with iTunes. I’ll occasionally scroll through their $4.99 lists and pick up things I might want to watch (and hopefully re-watch). The cheap ones usually work out. It’s the full-price movies I buy in a burst of hope that usually turn out to be unwatchable, even the first time… Downsizing with Matt Daimon being one of those.

They Came From Beyond Space sounds familiar… but that may be because of its echoes in Super 8 (Yes, I liked it).

Actually, you recommended It Came from the Desert to me!

Downsizing was a huge disappointment – worst Alexander Payne movie I’ve seen.