Pandemic viewing, Part Three

Continuing my roundup of what I’ve been watching in the past month or so of social isolation…

*

Evils of the Night (Mardi Rustam, 1984)

I mostly knew Mardi Rustam as the co-writer and producer of one of my favourite Tobe Hooper movies, Eaten Alive (1976), but even that didn’t prepare me for Evils of the Night, the first of two features he directed. Until the mid-’70s, Rustam was producing sleazy exploitation for people like Al Adamson and Greydon Clark; he took a step up with Ray Danton’s Psychic Killer in 1975, then the Hooper movie. When he got around to directing himself, he leaned towards Adamson rather than Hooper. Evils begins as a softcore teens-at-the-lake movie, with long drawn out sex scenes; then a UFO lands and someone starts killing off the teens. Turns out two sleazy rednecks (Aldo Ray and Neville Brand) have been hired by aliens to kidnap young people so their blood can be extracted to rejuvenate folks back on the home planet. John Carradine, Tina Louise and Julie Newmar run a hospital for the blood-harvesting. All of which sounds like more fun than it is … Rustam directs with no sense of pace, and apparently no sense of humour. (Vinegar Syndrome dual-format, alternate longer TV cut, director interview and outtakes)

The Hearse (George Bowers, 1980)

The ‘70s and ‘80s saw a spate of evil vehicle movies, beginning with Spielberg’s Duel (1971), followed by Killdozer, The Car, Christine, The Wraith, Maximum Overdrive … no doubt this stems from a deep-seated feeling of unease that we entrust our lives to these things which are bigger and more powerful than ourselves over which our control is often pretty tenuous. Editor George Bowers made his directorial debut with The Hearse, star Trish Van Devere’s follow-up to the The Changeling. Unfortunately this movie is much less effective. After her marriage fails, a woman returns to the old family home in a small town, empty for thirty years. The locals are all pretty hostile and a nifty old hearse keeps trying to run her off the road. Turns out the family was into Satanism and something is out to claim her for its own. (Vinegar Syndrome dual-format, with actor interview)

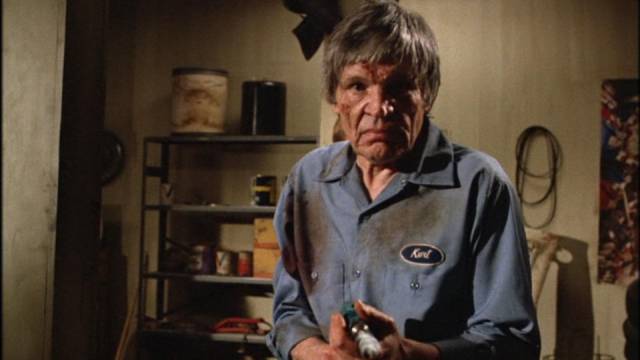

The Undertaker (William Kennedy et al., 1988)

Idiosyncratic character actor Joe Spinell’s penultimate movie virtually sank without a trace before it was ever released. Exhumed now, it can’t claim the status of a lost classic, but it does have its moments. Joe plays the local undertaker in a small New York town, an odd but respected member of the community who also happens to have pronounced necrophile tendencies which escalate to murder. His nephew suspects something and he becomes more and more unhinged. A prolific supporting actor (The Godfather, Taxi Driver, Big Wednesday, Cruising, Sorcerer…), when he took a lead role it seemed to bring out his inner demons. In The Undertaker and Maniac, he reeks of perversion and twisted psychology, inflicting pain and mutilation and crying about the horror of it all as he does it. He’s always fascinating to watch, even as he makes the viewer squirm. The big problem with this film is clumsy direction, with Joe often just standing there and giving long monologues to corpses he’s not even looking at – it’s frustratingly static – but there are some atmospheric moments. (Vinegar Syndrome dual-format, with director interview and commentary, plus outtakes)

The Children (Max Kalmanowicz, 1980)

My only vivid memory of the old Siskel and Ebert show was seeing them get almost apoplectic as they awarded The Children their “dog of the week” trophy back in 1980. Everything that outraged them was what made me like the movie when I saw it in a theatre back then, and it’s still one of my favourite low-budget horrors. But then, creepy evil kid movies have always appealed to me – from Mervyn LeRoy’s The Bad Seed (1956) to Wolf Rilla’s Village of the Damned, from Narciso Ibañez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? (1976) to Ed Hunt’s Bloody Birthday (1980), from Tom Shankland’s The Children (2008) to Jaume Collet-Serra’s Orphan (2009). Sociopathic children upend the foundations of society, making them a potent source of horror. In Kalmanowicz’s movie, a school bus drives through a toxic cloud spewed from a nuclear plant and the kids seek out their parents for hugs, only to burn the adults to a crisp with the radiation they’ve absorbed. It takes a long time for the sheriff and various parents to figure out what’s happening and realize the awful thing they must do to stop the deadly kids. (Vinegar Syndrome dual-format, with two commentaries and a stack of new and archival featurettes)

The Brotherhood of Satan (Bernard McEveety, 1970)

Before writing, producing and directing A Boy and His Dog (1975), actor L.Q. Jones produced a couple of interesting low budget horror films with his partner Alvy Moore. I’ve mentioned the first of these, The Witchmaker, before, but I only just got around to seeing the second, perhaps better known feature, The Brotherhood of Satan. One of the few theatrical features by long-time TV director Bernard McEveety, this modest film imaginatively reworks a fairly familiar theme – aging occultists appropriating the bodies of children or younger adults to extend their own lives (Peter Sasdy’s Nothing But the Night, Paul Wendkos’ The Mephisto Waltz). There are some effective visuals – the opening in which a toy tank becomes real and crushes a car – and a creepy atmosphere as a vacationing family find themselves trapped in a small town where some unseen force prevents them from leaving because Satanists want their daughter. (Mill Creek double-feature BD with William Castle’s Mr. Sardonicus, no extras)

Desecration (Dante Tomaselli, 1999)

The first feature of New Jersey filmmaker (and cousin of Alice, Sweet Alice’s Alfred Sole) is an odd, slippery piece of work, eschewing coherent narrative in favour of a kind of stream-of-consciousness nightmare steeped in Catholic iconography and guilt. A teenage boy, haunted by the death of his mother, accidentally kills one of the nuns at his oppressive school by losing control of his radio-controlled plane and crashing it into her head. Somehow this unleashes sinister forces which seem intent on dragging him to Hell. The influence of Eurohorror (people like Argento, Fulci and Rollin) as well as avant-garde experimental cinema is palpable. There’s some clumsiness and a few low-budget limitations, but Tomaselli strives for something more than familiar cheap horrors, and that’s refreshing. (Code Red BD, with director commentary, short film, featurette and a complete album of Tomaselli’s music)

The Intruder (Chris Robinson, 1975)

Yet another lost movie rediscovered. In this case, a single print was found among a stash of movies buried somewhere in the desert. Made for peanuts in Florida in the mid-’70s by writer, producer, director, star Chris Robinson (star of William Grefé’s killer snake movie Stanley [1972]), this blends old dark house mystery tropes with some proto-slasher elements, sometimes quite effectively. A group of people are gathered at a mansion on an island where their dead relative supposedly stashed a fortune in gold; they’re told they’ll be splitting the loot among themselves, but someone starts killing them off. There are some spooky moments, some effective murders, and a surprise twist at the end, but the script is weak and the pacing really uneven. The biggest surprise is seeing Mickey Rooney, Yvonne De Carlo, and Ted Cassidy in a movie reputed to have had a $25,000 budget. Nicely shot by Jack McGowan, who also shot Bob Clark’s Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (1972) and Dead of Night (1974), and Alan Ormsby and Jeff Gillen’s Deranged (1974). (GarageHouse Pictures BD, with commentary and archival interview with director Robinson)

Lady in White (Frank LaLoggia, 1988)

It always seems perplexing when someone with obvious talent makes just one or two movies, then disappears. I guess, when that filmmaker writes, produces, directs and also composes the score, maybe the sheer challenge of putting projects together, getting the money, then doing all the creative work defeats them. I have no idea whether that was the case with independent filmmaker Frank LaLoggia … maybe a bigger factor was the poor box office showing of his two films – the underrated Fear No Evil (1981), in which a teenager comes to realize that he’s actually Satan born in human form, and the well-reviewed but little seen Lady in White. I saw both in their brief theatrical runs and liked them both, but Lady in White surprised me for a couple of reasons: it was a far more polished film than its predecessor and in a way far more old fashioned. This is a classic ghost story about a young boy’s experiences with the spirit of a murdered girl in a small town which is also haunted by the titular lady. Woven through a sensitive and nuanced portrait of a community and the boy finding his place within it is a mystery about a pedophile serial killer, whose identity when it’s finally revealed is as traumatic as the ghostly encounters. The film is steeped in sadness more than horror (though there are some excellent scary scenes); it’s about coming of age and what is lost and what is gained as a child learns about the darker side of life. And yet, LaLoggia fills the denouement with a sense of hope emerging from tragedy. Thirty-plus years ago, I was a little disappointed because the film wasn’t outright horror like Fear No Evil … but I now see that it’s obviously a deeper, more heartfelt movie, richly layered and more rewarding. What a pity that Laloggia didn’t make more features. (His third and final appears to have been the direct-to-video Mother in 1995 … which I haven’t seen.) (Shout! Factory two-disk BD, with three different cuts, a commentary, deleted scenes and some behind-the-scenes material)

Hell Comes to Frogtown (R.J. Kizer & Donald G. Jackson, 1988)

Wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper made his feature debut with this cheap and cheerful New World Pictures sci-fi action comedy. (Later the same year, he starred in John Carpenter’s They Live.) In a post-apocalyptic world where fertile men are scarce, Sam Hell is unwillingly drafted for a mission into mutant territory to rescue some kidnapped fertile women – part of his job being to make them pregnant to help repopulate the devastated world. The kidnappers are the “frogs”, part-human, part-amphibian mutants led by Commander Toty (Brian Frank). Cheerful nonsense, unevenly paced, it knows exactly what it is and embraces its cheesiness enthusiastically. Steve Wang’s mutant makeups/animatronics are way better than the budget deserved, all the more impressive as he was only about twenty-one when he did the job right at the start of his career. (Arrow BD, with three interviews and an extended scene)

Demons (Lamberto Bava, 1985)

Having recently watched Demons 2, I picked up a sale copy of Demons, which I hadn’t seen in years. As I remembered, it’s a stronger film than the sequel because of its claustrophobic confinement in a movie theatre showing a cursed horror film. Once the cast is gathered and the lights go down, the action doesn’t let up – crude and splattery, it lacks the finesse of Lucio Fulci’s best work, but makes up for that in enthusiasm. (Arrow dual-format, with a pair of commentaries and three interview featurettes)

The Wind (Nico Mastorakis, 1986)

What Greek director Nico Mastorakis lacks in art, he makes up for with location – in a number of his movies, he makes spectacular use of remote Greek islands and villages. His best film (at least of the ones I’ve seen) remains his early feature Island of Death, a remarkably sordid tale of perversion and murder played out is a blindingly sunny village. Much of his later movie The Wind takes place at night, and the setting seems older and more ragged, with crumbling buildings and harsh cliffs (over which we can expect someone to plummet at some point). American mystery writer Sian Anderson (Meg Foster) rents a villa on a remote island where she intends to finish her latest book … only to find herself caught up in a plot much like those she invents when she sees the creepy caretaker (Wings Hauser) murder her landlord (Robert Morely). Isolated, beset by a powerful wind, with the phones not working, she has to fend for herself when the killer comes after her. Although visually atmospheric, Mastorakis often stages things clumsily, and for a woman who makes her living inventing mysteries, Sian is too often uninventive and helpless (making loud noises as she tries to hide, not finishing the job when she manages to stun the psycho more than once). The best things about The Wind are the setting and Meg Foster’s uncanny eyes. (Arrow BD, with director interview and the complete soundtrack by Hans Zimmer and Stanley Myers)

Deadly Blessing (Wes Craven, 1981)

Craven’s first studio-backed production (after Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes) is an atmospheric bit of rural horror about a rigid fundamentalist sect hostile to outsiders and harsh to any member who doesn’t strictly follow the rules. It seems that the intensity of their belief is itself the source of horror as a malevolent entity prowls the neighbourhood killing those who stray. The narrative line never quite comes into focus, and the whole thing is almost sunk by a producer-inflicted final shock which doesn’t make any sense, but Craven does a fine job of stirring up unease in a flat, sunny landscape. (Arrow BD, with director commentary and several interviews, mostly carried over from an earlier DVD)

Ash vs Evil Dead: Seasons 1-3 (Various, 2015-18)

I was a bit wary of the Ash vs Evil Dead franchise reboot, but a friend assured me it did justice to Sam Raimi’s beloved trilogy … and that turns out to be true. Over three seasons, Bruce Campbell’s blow-hard hero Ash is dragged out of retirement in a Miami bar when the Necronomicon resurfaces and various forces vie for possession, hoping to open the gates of Hell and let the Old Ones into our world. The cast is terrific, the writing as sharp as it was in the movies, the over-the-top gore often hilariously disgusting, and it finally climaxes on an epic scale which is really impressive. (Starz six-disk BD, with commentaries and an assortment of short featurettes)

Mamie Van Doren Film Noir Collection

(Howard W. Koch/Edward L. Cahn, 1957-59)

The 1950s saw the flourishing of a particular type of star, the breathy well-endowed blonde who apparently embodied many men’s sexual fantasy. Marilyn Monroe was the biggest of these, with Jayne Mansfield and Mamie Van Doren often seeming like less refined copies. In The Girl in Black Stockings, the first movie in this triple bill, Van Doren seems to be deliberately channelling Monroe in a small supporting role as just one resident of a Kanab, Utah, resort hotel where a number of people turn up dead. It’s a decent mystery with some good performances. Van Doren has a bigger part as co-star of Guns, Girls and Gangsters, in which she gets involved with an ex-con planning an armoured car robbery; problem is, her boyfriend has just broken out of the joint and is bent of jealous revenge. Van Doren gets to sing as a nightclub performer, Lee Van Cleef is intense as her vicious boyfriend, but Gerald Mohr is pretty dull as the robber. In Vice Raid, Van Doren works for a crime boss running a prostitution racket; she’s assigned to get a tenacious cop off the case by framing him for corruption. Kicked off the force, the cop goes it alone to bring down the racketeer … and naturally Van Doren repents and helps him. All three B-movies get nice transfers. (Kino Lorber two-disk set, with a brief interview with Van Doren about her career)

Baskin (Can Evrenol, 2015)

Turkey lacks a horror film tradition, so it’s not too surprising that writer-director Can Evrenol’s first feature draws on other sources for inspiration – Lucio Fulci and, particularly, the Hellraiser series. It’s an ambitious, but ultimately unsatisfying movie. The opening is strong as we’re introduced to a group of policemen who are drunk on their own power, using it to amuse themselves by tormenting people too weak to fight back. A mysterious radio call draws them to a remote area where strange things begin to happen; they end up running their van off the road and walking to an abandoned old police station which is apparently a portal to Hell. Following a vague narrative line that keeps circling back on itself, they descend into tunnels and cellars overflowing with bloody torment – bloody bodies being used and abused, perverse scenes of animalistic sex – until they finally meet a demonic figure who strives to make them see something lurking beneath the surface of life … or something. The gore becomes numbing and the narrative vagaries eventually dissipate the ominously suggestive opening stretch beneath literal horrors which tell us nothing. (Severin BD, with a making-of featurette and Evrenol’s original short film of the same title)

The Homesman (Tommy Lee Jones, 2014)

Tommy Lee Jones’ slow western finds more genuine horror in its depiction of madness bred in the isolation of pioneer life on the frontier than Evrenol’s overwrought feature. When several women succumb to madness under the stress of their hard lives (and brutal husbands), the local minister decides they must be sent back East into the care of good church people. But the only person willing to take on the arduous journey is tough, independent spinster Hilary Swank. She manipulates a crusty old vagrant (Jones) into helping her, and together the pair drive a wagon across the plains with the women locked inside. They encounter their own form of stressful isolation, intermittently broken by dangerous encounters and occasional violence. It’s a bleak vision of the limits of courage which ultimately leads to an ambiguously open-ended conclusion in which hope seems to be a fragile delusion. (Mongrel Media BD, with three short featurettes)

Impulse (Graham Baker, 1984)

I have a vague memory of seeing Impulse during its original theatrical run, but I didn’t recall much about it beyond the basic idea – a kind of lowkey echo of George Romero’s The Crazies (1973), with a touch of George C. Scott’s Rage (1972). A young couple return to the wife’s home town to find things have changed: normal social restraints have been stripped away and residents are acting on every impulse – road rage, suicide, murder. It all started with a chemical spill and sinister figures in unmarked vehicles are monitoring the situation as it deteriorates, preparing to cauterize the area to cover up the infection. I liked it more this time than when I saw it thirty-five years ago, its slow build allowing the horror to reveal itself gradually through ordinary behaviour pushed just slightly over the edge into madness. (Kino Lorber BD, with director commentary)

in Adam Egypt Mortimer’s Daniel Isn’t Real (2019)

Some Kind of Hate/Daniel Isn’t Real (Adam Egypt Mortimer, 2015/2019)

I’d never heard of Alan Egypt Mortimer until Arrow started promoting their release of his second feature, Daniel Isn’t Real, late last year. It sounded like something I might like, so I ordered a copy. And right after watching it, I ordered a copy of Mortimer’s first feature, Some Kind of Hate. And I liked that too. Both films deal with traumatized characters who draw on supernatural support to help them deal with their issues, only to find something worse being unleashed. In Hate, a bullied highschooler lashes out and is sent to a remote camp to have his behaviour fixed. Also bullied there, his anger summons the ghost of a girl who had been bullied at the camp a few years earlier and ended up committing suicide. He had just wanted to stop the bullies; she wants revenge against everyone. In Daniel, Luke, a boy with a dysfunctional mother, retreats into an imaginary world with a make-believe friend who leads him into trouble. Luke locks Daniel away, but years later, as a college freshman, stress brings Daniel back – more charismatic, more willing to take risks, and provoking Luke into dangerous situations. While Luke tries to negotiate life and a new relationship, Daniel becomes more aggressive and resentful, taking on a demonic force (literally). Both films are stylish, thoughtful, and unsettling … coming across them reminded me of discovering the films of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead a couple of years ago (also courtesy of Arrow). (Daniel: Arrow BD, with director commentary and interview, deleted scenes, festival Q&As, and a video essay; Hate: RLJ Entertainment BD, with two commentaries and some deleted scenes)

Comments

You’ve been busy! The only Turkish horror movie I’ve seen is Seytan, which is a scene by scene remake of Friedkin’s The Exorcist. “Seen” may be an exaggeration… skimmed through to confirm what it was, is more accurate. I’ve added Some Kind of Hate and Daniel Isn’t Real to my watch list… both available for streaming. Both look interesting.

Seytan sounds so bad I’m almost tempted to take a look … almost!