John Cassavetes’ Husbands (1970): Criterion Blu-ray review

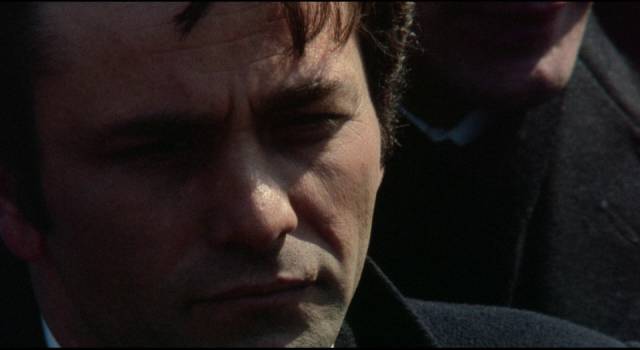

roughhousing in Cassavetes’ Husbands (1970)

John Cassavetes was an actor who turned to directing in order to further explore the actor’s process. Through a series of features over three decades, beginning with Shadows (1958), he became one of the godfathers of American independent filmmaking – his influence can be seen in the work of people like Richard Linklater and the whole Mumblecore movement. With little interest in technical and stylistic polish, Cassavetes used the apparatus of moviemaking largely to document his experiments with performance. Many of his films combined written scripts with a great deal of improvisation – and it seems apparent at times that the writing itself attempts to emulate the feel of improvisation.

Like Orson Welles, another fiercely independent filmmaker, Cassavetes had a parallel career as an actor in other people’s movies in order to support what he considered his real work; and like Welles, he didn’t seem particularly choosy about the roles he took, often displaying a kind of ironic detachment in his performances – an attitude which could have real dramatic impact in something like Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) or merely signal disdain in something like Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967).

After a decade of work, which included some episodic television and a rocky experience in the mainstream with the Stanley Kramer-produced A Child Is Waiting (1963 – hard to imagine an unlikelier pairing), Cassavetes had what amounted to an indie hit with Faces (1968), a raw and powerful story of infidelity in which a number of characters tear themselves and each other apart in a quest for the security of some kind of emotional relationship which always seems out of reach. Cassavetes’ attention to performance results in scenes which grow and evolve at their own pace, finding the sense of realism he was searching for even as the film borders on overheated melodrama.

That film’s success provided the impetus, commercially and creatively, for a bigger and more ambitious project. Financed with Italian money and produced by Al Ruban, who became a long-time collaborator from Faces on, Husbands (1970) follows the mid-life crisis of three middle-class suburban friends who are traumatized by the sudden death of another mutual close friend. They go on a long bender, then rush off to London for more drinking and gambling and screwing around before two of them reluctantly return home, leaving the third in England to look for a new life.

I last saw Husbands a long time ago and took another look (courtesy of Criterion’s new Blu-ray) largely because I’d found Cassavetes’ work interesting in their 2013 box set of five of his films. Watching it again, I was forcefully reminded of how much I disliked it. As Pauline Kael said in her New Yorker review, “Husbands extends the faults of his last film … one might even say that Husbands takes those faults into a new dimension.” Here, a striving for “realism” too often results in a paradoxically aggressive banality – “The man is right. When he’s right, he’s right.” Scenes go on interminably, but somehow we learn nothing about the three main characters that isn’t apparent from the beginning.

And what we do see of these men is unappealing. Faced with death, they reject the adult responsibilities which have apparently “trapped” them – their jobs, their wives and kids, and their suburban existence – retreating into rowdy immaturity. The desire for men to remain irresponsible boys is not an unreasonable subject, but here there seems to be no critical distance; the film itself embraces the trio’s toxic masculinity, withholding empathy from all the other characters, who exist solely to act as punching bags for the guys as they wallow in their self-pity and anger.

This is where the narrative’s dramatic limitations interact to grim effect with Cassavetes’ improvisational style. With only the three protagonists permitted any autonomous existence, Cassavetes and co-stars Ben Gazzara and Peter Falk relentlessly abuse the rest of the cast in scenes which drag on past the point of endurance. For half an hour, in a scene around a table in a bar, we watch them being loud and obnoxious and eventually overtly sadistic towards extras and bit players. While everyone is there to mark the passing of the dead friend, Cassavetes the director only has room to acknowledge the pain and grief of the three buddies, and pushes himself, Gazzara and Falk to inflict emotional torture on minor players who valiantly put up with it because they’re paid to be there. (If realism was the object, the other people at the table would at least have told the three of them to knock it off.) The hurt and confusion we see on one woman’s face as they abuse her doesn’t look like acting at all … perhaps this is the “truth” Cassavetes was looking for, but my sympathy was with the actress and not with the undefined character she was supposedly there to play.

This brutality is inflicted on a long string of performers, many of whom aren’t given enough definition to count as characters – Gazzara’s wife and mother-in-law are only there to be objects of his anger, props he can hit and choke to show just how much he dislikes the life he’s living. When Cassavetes picks up Jenny Runacre in a London casino and takes her back to his hotel room, he essentially rapes her, asserting as he does so that she “likes it” as she cries and tries to fight him off. Yet in the morning, for no psychologically comprehensible reason she expresses something like love for him, which prompts him to reject her.

Other women are used in equally unpleasant ways – the elderly woman in the casino who comes on to Falk is shot in a way which makes the very idea of female sexual desire a monstrous offence which undermines male authority. That unpleasant idea is reiterated in one of the film’s most bizarre moments. When the men return to the hotel with three women they’ve picked up, Falk finds himself with a young Asian who doesn’t speak; she lies there turned away from him, her cheeks wet with tears as he tries to get physical with her. We have no idea what’s going on inside her, but when she finally begins to respond to him, she starts to become dominant, getting on top of him and kissing him aggressively … and he angrily rejects her and pushes her away, ranting apparently because he hates the idea of her usurping his control.

Regardless of the individual qualities of the actresses in the film – they all remain barely sketched in, although some of the performances are very good (Runacre in particular) – all of them are there to be mere objects against which the three stars can bounce their self-absorbed, egotistical sense of their own importance. As an expression of toxic masculinity, Husbands succeeds with a vengeance … but it indulges in rather than analyzes or critiques that state, and it drags scenes out to such interminable lengths that you get the impression that Cassavetes is entirely in sympathy with these three obnoxious men and enjoys seeing the world through their murky perspective.

It’s interesting to note that much of his subsequent work centres on female characters played by his wife Gena Rowlands, herself a strong screen presence who counterbalances the hyper-masculinity represented by Husbands, transforming a film like A Woman Under the Influence (1974) into an examination of the very tendencies Husbands seems to embrace, finding those tendencies to be cruelly destructive.

*

The disk

The film looks excellent in the 4K restoration used for Criterion’s disk, with good colour rendition and contrast, though as always with Cassavetes visual style is not a consideration. Victor Kemper’s cinematography efficiently captures what’s going on without resorting to anything which might distract from the acting.

The supplements

In addition to a commentary from critic and Cassavetes expert Marshall Fine recorded in 2009, the disk has two hours of video extras, some archival, some new. The former are an episode of the Dick Cavett Show from 1970 (33:32), with Cassavetes, Falk and Gazarra promoting the film; and a retrospective from 2009 (29:46), with collaborators extolling Cassavetes’ talents as both filmmaker and actor. The new material consists of interviews with producer Al Ruban (25:02) and actress Jenny Runacre (17:55), who offers praise of Cassavetes along with some conflicted feelings about what she was put through during the shoot; and a video essay by Daniel Raim (12:59) which uses audio clips of Cassavetes talking about his approach to acting.

There’s also a trailer (3:44) and the booklet essay is by Andrew Bujalski, who acknowledges Cassavetes’ influence on the indie movement of which Bujalski himself has been a major part.

Comments