New features by two favourites

As tedious as the pandemic lockdown has become – I had no idea how fed up I could get with my own company – there have been a couple of bright spots this Spring. (First World privilege speaking here!) I’ve just seen new features by two favourites who have been missing for far too long. Larry Fessenden’s Depraved and Richard Stanley’s Color Out Of Space (both 2019) are everything their fans and admirers could hope for and more – smart, stylish and emotionally resonant horror movies which echo genre traditions while making those traditions fresh again.

*

Depraved (Larry Fessenden, 2019)

I first encountered Larry Fessenden’s work in the Fall of 1998 when I was living in Toronto and attending the Canadian Film Centre (a whole other story – a terrible institution dedicated to erasing every trace of originality from its residents[1]). I used to go regularly to the famed Bloor, a repertory theatre which changed its schedule pretty much every day. (I was visiting friends in Toronto in 1982 when I attended the world premiere of Ed Wood’s Revenge of the Dead at the Bloor.) I knew nothing about Fessenden when they screened his second feature, Habit (1995), one evening several years after its release – and discovered the best modern vampire film since George A. Romero’s Martin (1977). Fessenden’s rare subsequent features never had that kind of impact on me, but Wendigo (2001) and The Last Winter (2006) were both thoughtful movies which hung their horror elements on well-developed characters and themes (as did his first feature, No Telling [1991], which I caught up with a bit later).

But then, as a writer-director, Fessenden fell silent, devoting his efforts to supporting other independent filmmakers through his company Glass Eye Pix, often appearing in supporting roles and cementing his position as a fine character actor. I was thrilled to see his name on a new film in 2013, only to be disappointed by the silly, cliched Beneath, which he had taken as a job-for-hire (it aired on the Chiller cable channel and got really bad reviews). Six more years passed before he made another feature, but this time it was a personal project which he had been nurturing for a long time. His original plan had been to make Depraved on a bigger budget with name stars, but the mechanics of putting that together kept pushing it further into the future. So eventually he fell back on the Glass Eye Pix ethos of just getting it done with whatever resources were available.

Without the obligations and pressures of studio backing, Fessenden obviously felt liberated and ended up making his best film since Habit, small in scale but not cramped, with a powerful emotional impact. Depraved does for Frankenstein what Habit did for vampires, bringing a familiar cultural myth into a contemporary setting and exploring its psychological and moral implications with intelligence and subtlety.

Henry (David Call) saw horrific things as a medic in Iraq and deals with his trauma by experimenting with ways of repairing bodies smashed by war … ways of not only extending life, but of actually restoring life after it has been extinguished. Working in a New York loft fitted with his own private medical lab, Henry is financed by an old college buddy named Polidori (Joshua Leonard), who manages to keep him supplied with relatively fresh bodies.

Henry is so intensely focused on his work that he doesn’t stop to ask questions. Polidori’s motives are naturally far less altruistic. In addition to the bodies, he supplies Henry with an experimental drug which not only facilitates transplants but also has powerful restorative effects on dead tissue. The drug has been developed by a company owned by Mr. Beaufort (Chris O’Connor), whose money, filtered through Polidori, is supporting Henry’s research.

When the body Henry has pieced together from parts awakens, his concern is to teach it how to be human; Polidori just wants to use it to sell the drug. Named Adam by Henry, the creature (Alex Breaux) rapidly progresses from infancy to a being striving to comprehend the world into which he has been born, an emotionally immature being with no social skills to manage his instincts – or to properly deal with the memories which begin to surface in the brain implanted in his head. That brain came from a young man named Alex (Owen Campbell), who had just had an argument with his girlfriend Lucy (Chloe Levine) when someone stabbed him to death on the street. That someone was Polidori, harvesting the final component needed by Henry to complete his creation.

As things fall apart, Henry is forced to confront the dark side of the work he’s been doing. As in Mary Shelley’s original story, the eventual violent actions of the creature are a result of the creator’s blindness and moral failures. By the time Henry wises up and rebels against the use to which he’s been put by Polidori, it’s too late … facing the horror of his existence Adam seeks revenge and Fessenden moves from naturalism into an all-out homage to James Whale’s Universal horrors of the early ’30s. Somehow, this stylistic shift works, carried by our identification with Adam’s point of view.

Although much of Depraved takes place in the confines of Henry’s loft, Fessenden’s use of camera and editing give it a sense of scale and it certainly doesn’t look like a low budget movie. A very good cast helps with that. Call convincingly conveys the inner PTSD demons which drive him, and Leonard is good as a guy without much talent of his own who knows how to exploit others for profit. But what makes the film really hum is Breaux, who gives a remarkable performance as Adam, a fascinating combination of physicality and increasingly complex emotional states. In this instance, all the frustrating delays Fessenden experienced in developing the film paid off; he needed to wait until this particular actor came along for the film to coalesce around a performance it would be hard to envisage anyone else giving.

The Scream! Factory/IFC Blu-ray has excellent image and sound, a commentary from Fessenden, and almost two hours of video extras, including a 76-minute making of, and four featurettes covering the origins of the project, the complex full-body makeup for Adam, Breaux’ approach to the role, and the look of the film. It’s a terrific package, which celebrates Fessenden’s return to directing and confirms his position as one of the genre’s finest modern practitioners.

*

Richard Stanley

You get to know some filmmakers because you discover and love their work; but occasionally you get to know the filmmaker before you experience their work and come to love the work because the creator takes hold of you imagination. For me, Richard Stanley falls into the latter category. He’s a fascinating, eccentric character who has a strange, almost hypnotic hold on me. But it didn’t start that way.

I knew nothing about him when I saw Hardware in its original theatrical release in 1990. Back then, I thought this was a fairly derivative sci-fi/horror hybrid, borrowing particularly from The Terminator, its chief interest being the director’s obvious skill at image-making. For a low-budget feature, it has a dense, richly-designed look which raises the story somewhat above cliche. It seems more impressive when you learn that the writer-director was only in his early twenties when he made it.

At some point, I heard about his second feature, Dust Devil (1992), but it had a troubled release and was hard to see. Then came reports of the disastrous attempt at a high-budget third feature, Stanley’s long nurtured adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau from which he was fired after just one week of shooting by New Line’s Robert Shaye. Rumours ran wild – Stanley had gone mad, living in the jungle near the shoot, spying on the production… That story was eventually told in great detail by David Gregory in his documentary Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (2014). But by the time I saw that, I’d seen most of Stanley’s work and gained a better sense of his idiosyncratic personality.

The big breakthrough came in 2006 with the release of Subversive Cinema’s generous five-disk DVD set somewhat misleadingly presented as a Limited Collector’s Edition of Dust Devil. This set provides a masterclass in all things Stanley and cemented my interest in and appreciation of his work. Not only did it present two cuts of his second feature – a visually gorgeous, evocative, mystical contemplation of loneliness and death set on the desert backroads of Southern Africa – it also included three of Stanley’s documentaries (offering insight into his view of the world – art, history, religion), plus interviews and commentaries which brought his distinctive personality into sharp focus. Who Stanley is becomes inseparable from the work he creates, which is not always true of even a good filmmaker. (When Severin brought out a two-disk DVD edition of Hardware three years later, I was in a better position to appreciate what the young Stanley had accomplished, and the addition of a commentary, making-of, deleted scenes and several short films, including a super-8 trial run for Hardware, reinforced my interest in and appreciation of Stanley as a distinctive artist.)

The documentaries reveal a restless, risk-taking artist. He was barely in his twenties when he snuck into Soviet-occupied Afghanistan with a cameraman (who had to be sneaked out of the country after being shot) to record an impressionistic portrait of an ancient nation immersed in what amounted to a centuries-long war (only the invaders changed over time). Voice of the Moon was completed the same year he made Hardware. Equally impressionistic is Stanley’s exploration of the continuing practice of Voodoo in Haiti, The White Darkness (2002), which makes a worthy companion for Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen (unfinished at her death in 1961, but released as an assembly of raw footage in 1985).

But what completely sealed my admiration for Stanley was The Secret Glory (2001), a feature-length documentary about SS officer Otto Rahn who, with the sanction of the highest levels of Nazi authority, embarked on a search for the Holy Grail. Here was a story of madness and obsession in which Fascist politics intersected with the occult (yes, just like Raiders of the Lost Ark). The strange connection between the Nazis and magical thinking has been well-known for a long time, though often relegated to the fringes of history because we tend to want to find rational reasons for the things people do, but here was an actual story which put the occult closer to the centre of the monstrous Nazi project.

Making the film also forged a connection between Stanley and an area in France important to Rahn’s quest. Montségur, with a history of habitation going back 80,000 years to the Neanderthals, is best known to history as the final stronghold of the Cathars, a sect declared heretical by the Catholic Church and destroyed in 1244, when hundreds were burned at the stake after a siege by 10,000 French troops. Legend has it that the Grail was kept at the fortress of Montségur, but smuggled out before the Cathars surrendered. Now the area draws people who sense a mystical connection, believing that there’s a kind of gateway to other realms. Those people and their beliefs form the basis of Stanley’s documentary feature The Otherworld (2013), which gradually builds to an account of his own paranormal experience of penetrating the thin veil between worlds.

Between the collapse of Dr. Moreau and the release of The Otherworld, Stanley made only a handful of shorts and those two documentaries, The Secret Glory and The White Darkness, but the distinctive, often eccentric character of his small body of work steadily built a fan base … and with the dramatic changes resulting from the rise of digital filmmaking, which has lowered the cost of independent production without necessarily sacrificing quality, it was probably only a matter of time before some passionate fans would take a chance on backing him in a new project.

That group of admirers ended up including actor Elijah Wood, who with his producing partners Josh C. Waller and Lisa Whalen had already made out-of-the-mainstream features like Panos Cosmatos’ Mandy (2018) and Adam Egypt Mortimer’s Daniel Isn’t Real (2019). When Stanley’s script for an H.P. Lovecraft adaptation arrived on their desks, they saw it as a no-brainer and quite quickly cast and crew were shooting on location in Portugal … two-and-a-half decades after Stanley had last shot a narrative feature.

*

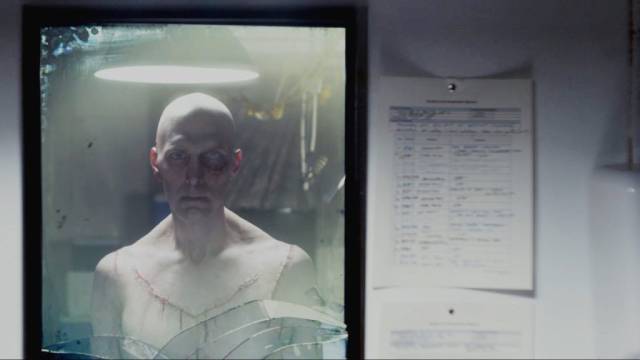

in Richard Stanley’s Color Out Of Space (2019)

Color Out Of Space (Richard Stanley, 2019)

It’s a paradox that so many films (amateur and professional) have been made from the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, but not so strange that few of them bear any real resemblance to their inspirations. Lovecraft didn’t write much in the way of narrative; most of his work is devoted to creating an atmosphere of all-encompassing dread. His prose is dense (or less politely, verbose), piling on descriptive phrases which often remain so vague that what’s being described is left up to the reader’s imagination. But underneath that often frustratingly unspecific surface, he evoked a deeply pessimistic view of existence in which humanity is an uninformed pawn being manipulated by vast, malevolent cosmic forces – the Elder Gods and Great Old Ones – which are constantly trying to re-enter our world from the Outer Darkness.

It’s the mood, the vision of our insignificance and helplessness, which appeals to the writer’s fans. With little in the way of character and narrative to hang a movie on, filmmakers have to extrapolate and invent in their quest to evoke that cosmic dread, most often falling short because the more that specific details are added to Lovecraft’s situations, the more the dread is diluted. Another paradox: some of the more enjoyable adaptations aren’t actually scary, but are rather pastiches of Lovecraft’s method – for instance, the two features produced by the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society, Andrew Leman’s The Call of Cthulhu (2005) and Sean Branney’s The Whisperer in Darkness (2011), both of which have enormous charm but are by no means scary.

One story which has inspired many adaptations, going back to Daniel Haller’s Die, Monster, Die! in 1965, the second known feature based on the writer’s work (after Roger Corman’s The Haunted Palace [1963]), is The Colour Out of Space (1927), no doubt in part because it provides a high-concept idea which leaves a lot of leeway for filmmakers to invent their own narrative details. A meteorite crashes on a farm in remote New England and apparently emits an unknown form of radiation (the “colour”) which initially boosts the growth of the farmer’s produce; but the resulting vegetables are inedible, as is the meat from his animals. His wife and sons become insane, and the colour eventually destroys everyone on the farm and contaminates the surrounding region before it flies back into space.

In the decade leading up to Richard Stanley’s version of this story, there have been at least three others – an experimental short (2017) by German filmmaker Patrick Müller; Die Farbe (2010), a German feature by transplanted Vietnamese filmmaker Huan Vu; and a more freeform (and uncredited) adaptation by Swedish experimental filmmaker Henrik Möller, Feed the Light (Lokalvardaren, 2014) – all of which are very different from Stanley’s film while still having their roots in Lovecraft.

Stanley’s script maintains the general elements of the original, but naturally builds up the characters to foreground a dramatic thread rather than just using them as a hook for the horrific situation. He incorporates Lovecraft’s narrator – in the story, an unnamed surveyor who hears the tale from locals; here a hydrologist named Ward (Elliott Knight) surveying the valley for a proposed dam – but relegates him to the sidelines for most of the film. The primary focus of our attention is Lavinia Gardner (Madeleine Arthur), the daughter of Nathan Gardner (Nicholas Cage) and his wife Theresa (Joely Richardson), who have retreated to Nathan’s family’s farm after Theresa’s treatment for cancer. He’s trying to make a go of the farm (vegetables and alpacas) while she tries to maintain her business as a financial advisor over the phone and an unreliable internet connection.

Ward first encounters Lavinia performing a Wiccan rite on a river bank – wanting her mother to recover fully, but also hoping to escape from the farm which she hates. Initially angry when Ward interrupts her, she softens when he shows some knowledge of the occult arts. Camping in the valley, Ward becomes a witness to what happens to the family after a meteorite crashes near their house. As in the story, the rock seems to spur plant growth – colourful flowers sprout up in the yard, and eventually Nathan finds huge tomatoes growing very early in the season – but there are also creeping psychological effects; the youngest son Jack (Julian Hilliard) seems to see and hear things not apparent to others; the tensions in Nathan and Theresa’s marriage rise to the surface and he begins to drink more. Stoner brother Benny (Brendan Meyer) and Lavinia hold out the longest, seeing madness gradually claiming the family.

Stanley manages to create an atmosphere of encroaching gloom, getting good performances from the cast and perhaps more importantly creating lush visuals with the aid of cinematographer Steve Annis (just his third feature after a decade of music videos); given the story’s central conceit – that the meteor emits radiation in the form of a colour unknown to human eyes – these visuals are obviously critical and the film becomes increasingly exotic as the purple-pink colour permeates the farm in wisps which grow into swirling clouds of unnatural ectoplasmic mist.

Stanley’s ability to create striking images, both tactile and ethereal, is on full display, making this his most beautiful work yet. That beauty creates a tension with the growing madness and the ultimately downbeat conclusion – Lovecraft’s horrors are always, in the end, inescapable. Despite all the time which has passed between features, Stanley shows a real ease here with a fluid camera, elegant framing, and economical scene composition.

But for all its pleasures, this is not to say that the film is perfect. There are derivative elements which a little too strongly remind you in distracting ways of other movies. What happens to Nathan’s alpacas in the barn is close to what happened to the dogs in the kennel in John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982); and in quite a few scenes, Nicholas Cage seems to be channelling Jack Torrance from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1979). But that said, Stanley does manage to rein in Cage’s typical excesses while making effective use of his familiar derangement to create an uncomfortable instability for Lavinia and Benny to navigate as they see the family being slowly destroyed by incomprehensible forces. For me, perhaps the weakest element of the film is the way Stanley fails to work Lavinia’s ceremonial magic into the larger narrative – it feels like a dropped thread, all the more noticeable because it’s what the film opens with.

I had been waiting with intense anticipation for this movie since I first heard about it last year and I’m happy to say that it didn’t disappoint me – none of the points just mentioned do serious damage. After all this time, Stanley remains a rewarding talent and I hope he manages to continue with the other two Lovecraft adaptations he wants to do.

It would have been nice if RLJE Films had enhanced the disk with extras comparable to those on the Depraved Blu-ray, particularly given that this is such a significant return to the screen by a filmmaker who has been so long absent; but all we get is a selection of brief deleted/extended scenes and a twenty-minute making of, which mostly consists of admiring comments from cast and crew about working with Stanley. But that of course remains a minor quibble; what matters is that Richard Stanley has returned and he’s done it with a fantasy which lives up to the standard of his previous work.

NOTE: My enthusiasm for Color Out of Space and its director became retroactively problematic nine months later when Stanley’s history of abusive violence towards a number of women became widely known.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) The experience of my cohort can be summed up by one brief anecdote: at the end of the year, after an exhausting struggle to complete the short film being made by the team I was part of, one of the top administrators was chatting with someone she didn’t know was a friend of ours and she commented that our team had made that year’s best film but none of us were fit to work in the industry because we wouldn’t do what we were told. (return)

Comments