A frustrating evening

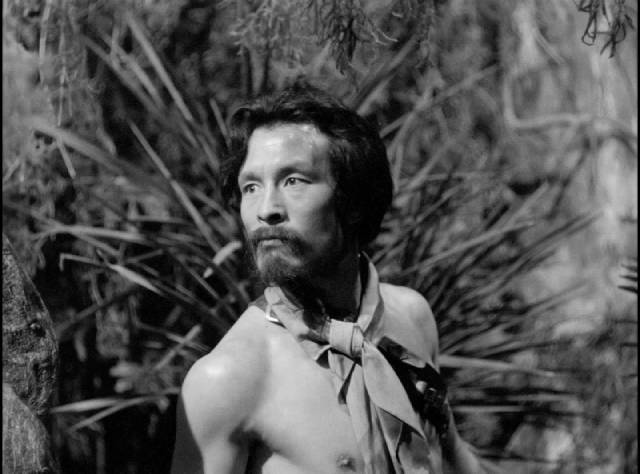

in Josef Von Sternberg’s The Saga of Anatahan (1953)

My friend Howard came over recently for dinner and a couple of movies and it may well have been our oddest evening yet. We watched two films which couldn’t be more unlike one another, yet by an odd coincidence both made use of an unreliable narrator to complicate what initially appeared to be straightforward narratives. And both left us somewhat frustrated and unsatisfied … which at least prompted some lively discussion.

These two films, as absurd a double bill as you could imagine, have been handled with care by their respective distributors – Masters of Cinema for Joseph Von Sternberg’s final feature, The Saga of Anatahan (1953), and Indicator for Sidney Gilliat’s final feature, the Agatha Christie adaptation Endless Night (1972). Von Sternberg was fifty-nine when he made the film and, although he lived sixteen more years, he never made another; Gilliat was sixty-four and he lived another twenty-two years. These statistics are essentially irrelevant, other than that on a superficial level their respective films’ commercial failure appears to have played a part in ending their careers. In all other respects, the two filmmakers had nothing in common.

*

The Saga of Anatahan (Josef Von Sternberg, 1953)

Von Sternberg was a conscious artist, whose work often defied commercial imperatives; his best films were crafted with obsessive care, using the screen – and his actors – in abstract ways to create complex imagery from light and shadow which might reference the actual physical world, but existed on a feverish conceptual plane which formed a ground for the director’s obsessive exploration of sexuality in all its pleasurable and destructive dimensions.

Von Sternberg’s fortuitous alliance with Marlene Dietrich facilitated those obsessions; he crafted in her one of the most distinctive star personas in early sound cinema, and her commercial appeal in turn allowed him, for a brief five years, to create some of the most perverse movies ever financed by a major studio. When their professional relationship ended in 1935 after The Devil is a Woman, their sixth and final film together, she went on to a long and successful career, while he never quite recovered. This anyway is my broad understanding of what happened. To be honest, I’ve only seen a fraction of Von Sternberg’s work – the three silent films released by Criterion in 2010, and at most three of the Dietrich films (The Blue Angel, The Scarlet Empress and possibly Shanghai Express), plus The Shanghai Gesture, which hearkens back to the Dietrich movies, but somewhat lacks the obsessive quality she once provided.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that I was not fully equipped to grapple with The Saga of Anatahan when I finally saw it. I’d first become aware of the film when I read Jonathan Rosenbaum’s 1978 essay about it, reprinted in his 1995 book Placing Movies. That essay posits the film as a strange, misunderstood masterpiece and Rosenbaum’s description of Von Sternberg’s use of an artificially fabricated setting and a complex use of sound planted a particular impression in my mind, which lingered in the ensuing twenty-five years but, in the event, still left me quite unprepared for the experience of watching the film.

Anatahan functions on multiple levels simultaneously, seeming to present the viewer with a complex code that needs to be deciphered … a puzzle which left me frustrated and confused on this initial viewing. The “story” is actually quite easy to grasp: based on an actual incident which Von Sternberg had recently read about when Japanese producer Nagamasa Kawakita invited him to make a film in Japan, it tells of a number of sailors who were stranded on a small island in the Marianas when their ship was sunk in 1944. On the island they find a man and woman (whom they initially assume to be husband and wife) and over the next seven years, the tensions produced by this imbalance stir a cycle of desire and violence, which only ends when the survivors are finally taken off the island and returned to Japan.

There were many cases of Japanese soldiers who lingered on in the Pacific, either not knowing that the war had ended, or if they had heard refusing to believe it because the idea that Japan had lost was simply beyond comprehension. At several times during the film’s seven years, they do hear the news (over loud speakers on passing American ships, in leaflets dropped from planes), but the stranded men think these are just enemy tricks and they cling to their duty to “defend” the island.

All of this is clear and realistic, but for Von Sternberg it just forms a pretext for what really interests him. With the passing of time and the presence of a single woman, as in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (published a year after the film was made), social structure breaks down and a more primitive form of competition takes over. It doesn’t take long because most of the men are recent conscripts, fishermen dragged into the war without a foundation of ingrained military discipline. Subject to a now aimless duty, the men’s energies become focused on Keiko (Akemi Negishi), a young woman who soon becomes aware of her power. Von Sternberg maintains ambiguity about her own feelings and motives – whether she relishes that power or uses it defensively to protect herself to some degree from the danger the men present.

Although certain things are elided, it seems clear that she is subjected to some violence. Her husband Kusatabe (Tadashi Suganuma) initially maintains a degree of jealous control, but his possessiveness ends up working against him; Keiko is drawn to one or another of the stranded men, exercising her own sexual desire. As time passes, each lover is killed and replaced by another in a serial competition for dominance, until the men decide to use a less deadly method to assert their “rights” over Keiko, drawing lots. But by then she’s had enough of them and runs away, managing to attract the attention of a passing ship.

With her departure, the strange hermetic little society which has been trapped in that cycle of desire and violence is finally broken open. Through Keiko’s efforts to contact the men’s families back in Japan, and the delivery to the island of personal letters pleading with the men to come home, the world which has shrunk so claustrophobically is suddenly reopened. The men are liberated and rejoin their families – all except the one career soldier among them who can’t bear to accept the idea of defeat and remains alone on the island.

As a narrative this could easily have been presented as a piece of naturalistic storytelling – even without subtitles for the Japanese dialogue, it’s entirely comprehensible. But Von Sternberg obviously had something else in mind. First of all, as was his preference, he avoided actual locations, except famously for shots of a rocky coast and the real sea (which is repeatedly associated with a naked Keiko). Preferring the high degree of control he could have in a studio, he also created deliberately artificial-looking sets. He wasn’t trying to simulate reality the way a conventional Hollywood director might by building a jungle on a soundstage. Rather, he created a conceptual space with plants, cellophane and silver paint; as in his Paramount films, this results in a dense, almost two-dimensional canvas composed of intricate patterns of light and shadow with the characters often drifting through the frame like wraiths.

In addition to this visual stylization, Von Sternberg added another complicating layer to the film with a voiceover narration, which occasionally paraphrases the Japanese dialogue or describes the action which is occurring, or has just occurred, or is about to occur, while additionally adding philosophical observations about human behaviour or interpretations of the characters’ motives or emotional states. And yet this is not some voice of God know-it-all. Spoken in a flat monotone (by Von Sternberg himself), it uses the second person “we”, identifying itself with the shipwrecked men as a group, something like a Greek chorus embedded in the narrative.

And yet this voice continually calls itself into question. It contradicts what we see, it claims imperfect knowledge – “we can’t know exactly what happened because we weren’t there, but even if we were, we would all have a different account of events”. Rather than clarifying or giving privileged access to what happens on the island, the voiceover has a distancing effect, mystifying what otherwise might seem quite clear and comprehensible. In the final moments, as the castaways arrive back in Japan, the voice supposes that Keiko was also at the airport to see them return … but it is the five men who died in competition for her whom she sees… There’s a melancholy tone to this coda and a suggestion of forgiveness and understanding. But I’m not at all sure that I know what Von Sternberg was actually getting at. These men all died “because of” Keiko, and yet it was her decision to escape the cycle of sexual desire and violence, to return to the world, which ultimately frees the surviving men who were incapable of helping themselves.

There are other things going on in the film to complicate an easy reading. Despite the determined artificiality of the style, at the halfway point Von Sternberg abruptly cuts to a documentary montage of Japanese soldiers and sailors returning home at the end of the war, a mixture of joy and sadness, relief that the ordeal is over but shame and anger that it ended in defeat. When we return to the island after this interlude, it seems even more detached from reality, even more of a state of mind than a stage for dramatic action.

When the film was over, my impressions were a jumble of confusion; the various elements hadn’t created a harmonious whole for me, but rather fought against each other. I was quite frequently irritated by the voiceover which kept getting in the way of what might have been an engaging drama, but that drama itself often lingered at length on seemingly tangential moments while eliding significant action – the killing of Kusatabe, surely a significant turning point, is tossed away off-screen. Perhaps my frustration stems from a feeling that Anatahan is beyond my critical skills, that I’m not up to interpreting it. After watching it, I went back and reread Rosenbaum’s essay and what twenty-five years ago had piqued my interest now seemed just as dense and confusing as the film itself. The extras on the disk didn’t help much either – a forty-five minute interview with Tony Rayns fills in the story of the production and its place in Von Sternberg’s career; a sixteen minute visual essay by Tag Gallagher examines the visual style and use of sound; and Von Sternberg’s son Nicholas speaks about his father and the experience he had working in Japan … while these all fill in peripheral details, they somehow don’t clarify the odd experience of actually watching the film.

The disk includes both the 1953 theatrical cut and the 1958 uncensored director’s cut. The main difference is the inclusion of several sequences in which Akemi Negishi is nude, overtly erotic imagery which would’ve been unacceptable to the Production Code in 1953. There are also some instances of scenes being cut slightly differently – a brief featurette details the variations.

One interesting side note: the miniatures and effects were the work of Eiji Tsuburaya and the score was by Akira Ifukube, just one year before they contributed remarkable work to Ishiro Honda’s Gojira (1954).

*

Endless Night (Sidney Gilliat, 1972)

The problems with Sidney Gilliat’s Endless Night are much less complicated. This is, after all, a commercial movie, not an attempt at art which is more interested in the intricacies of cinema than simply telling a story. Gillìat himself had a long and noteworthy career in the British industry, much of it in partnership with Frank Launder; together they wrote scripts, produced, alternated as director, and twice co-directed. Both had been in the business for some years when they made their indelible mark by collaborating on the script of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes in 1938, setting a standard in wit and clever plotting that remained a high point in their own careers.

It was another five years before they wrote and directed one of the best British home front movies, Millions Like Us (1943). Their films together and alone are quite varied, thrillers alternating with comedies and straight dramas. The second-last movie for each, which they co-wrote and co-directed in 1966, was one of a series of comedies about an appalling girls’ school called St. Trinian’s. Six years later, Gilliat wrote and directed this Agatha Christie adaptation with Launder executive producing.

Endless Night is something of a hybrid, very different from the more familiar Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple mysteries. It seems closer to something by Daphne DuMaurier, a romantic mystery with buried secrets and psychological twists. In fact, its opening moments seem to deliberately echo Rebecca, with the protagonist’s voice remembering the first time he saw a particular place and a particular person who would change the course of his life. That, of course, is the big difference – the troubled, neurotic narrator here is a man rather than a woman.

This opening moment quickly stalls in neurotic uncertainty. The memory we are seeing is dramatically fractured in a series of rapid tracks-in on a woman standing in the English countryside, the colour shifting radically with each repetition as if the memory can’t quite be pinned down. And then suddenly, as the voice continues, we see two pairs of feet walking on a gravel path. A second voice interrupts, asking the first to begin again … from the beginning.

We realize that we are in the grounds of some institution, that the storyteller is a patient/inmate and that the second man is some kind of investigator/therapist. From here, we see the story in flashback, but we’ve already been primed to distrust what we hear.

The man telling us this story is Michael Rogers (Hywel Bennett), a working class guy who believes he was meant for better things. The story he tells begins at an art auction, where he bids up the price of a small oil painting before losing it to another bidder. He leaves the auction and walks to a Rolls Royce, reaches inside … and comes out with a chauffeur’s hat just in time to help a wealthy woman put her shopping in the car. Michael is a fabulist, constantly inventing a better life for himself. He drops in on his mother and tells her about the auction; she’s obviously worried and warns him that he’ll lose his job “again”. Irritated, he tells her that she just doesn’t understand, that for the brief moment between bids he “owned the painting”.

His job as a driver for a car hire company gives him opportunities to elaborate on his fantasies. It also allows him to subtly (and not so subtly) express contempt for the wealthy people he drives. He’s smarter than them and has better taste. A trip to Italy introduces him to someone who recognizes his better qualities, the famous architect Santonix (Per Oscarsson), who is building a villa for Michael’s current client. When the client quickly flies off by helicopter for another meeting, Santonix gives Michael a tour and the conversation ends up on Michael’s dream of building a fabulous house on a hillside overlooking the sea – this is the place he introduced at the start of the film – and the architect says that if Michael ever gets the money, he’ll design the house for him.

From this point, everything miraculously falls into place. Visiting his dream site one day (after having been fired for being rude to a customer), Michael meets the woman he had difficulty remembering clearly in that moment at the start of the film. She is Ellie Thomsen (Hayley Mills), about whom all we know at this point is that she is pretty and, believing herself alone, she takes pleasure in dancing on the hillside in the sun. In fact, she has the quality of a romantic fantasy, a role she continues to fill in the story Michael is telling.

There is something very old-fashioned yet satisfying about this story. Michael falls in love with Ellie and she responds … and yet there are small signs of potential trouble; she misses rendezvous, then calls to apologize. And then he discovers something in the paper that alters everything: she has just come of age and inherited a massive fortune. This triggers his class resentments, he feels that she must have been toying with him … and when he learns that she has bought the piece of land he wants to possess, he becomes angry at her taking control, undermining his masculine pride. But she manages to convince him that she really does love him and they slip away to get married.

Needless to say, this causes problems with her family – a stepmother and her new husband, both expressing crass snobbery and expecting the obvious gold-digger to accept a pay-off by family lawyer “Uncle” Andrew (George Sanders in his final role; he committed suicide before the film was released). When Michael refuses, there are half-spoken warnings, particularly about Ellie’s German companion Greta (Britt Ekland)… In fact, Michael is warned about her by several people, including Santonix; he must not allow her to insinuate her way into his life with Ellie.

With Ellie’s money, Santonix is hired to build the dream house, something he does with a sense of urgency because (for some reason) he is terminally ill. This house takes on great symbolic importance – a big modernist structure on the brow of the hill, with multiple remote control functions including entire walls which slide aside to reveal the rolling landscape and the sea beyond, plus improbably a living room floor which rolls open to reveal an indoor swimming pool. And so working class Michael has attained all he has ever fantasized about – a princess and castle, and an antique store in town where he can display his knowledge and taste.

But as in any fairytale there are shadows at the edges of his happiness – Ellie’s family, who take a summer place nearby and hang around annoyingly; and worse, Greta, who comes to stay and quickly imposes on them, dominating Ellie and trying to push Michael aside. Then there’s old Mrs. Townsend (Patience Collier), who prowls the hillside with a pair of Siamese cats on leashes and offers cryptic warnings about the land being cursed – she claims that she’s the last surviving member of the family which owned the land, all the others having died horribly.

As in Rebecca, the dream of romance and material success is somehow too good to be true, but we can’t be sure just what the problem is … and would do well to remember that what we see and hear is coming to us mediated through Michael’s perceptions and memories. Nonetheless, the slowly unfolding romantic fantasy is engaging – we can empathize with Michael’s doubts and fears because we know they are rooted in those class resentments; he’s the underdog who is making good. And there’s real chemistry between Bennett and Mills which makes us root for the couple. (They had previously been paired in Roy Boulting’s psycho-thriller Twisted Nerve [1968].)

[Spoilers]

But no fantasy can last indefinitely. At the height of our satisfaction, the rug gets pulled out from under us. Ellie dies suddenly in a riding accident.

At this point, we’d do well to remember Hitchcock’s distinction between suspense and shock: a scene takes place in a room and at the start we see someone place a bomb under the table … as the inhabitants of the room discuss some mundane matter, we wait for the bomb to go off. That’s suspense. The audience knows something the characters don’t, we know something terrible is going to happen. On the other hand, we have a scene in a room with characters discussing trivialities and then a bomb suddenly goes off. We’re shocked, but there has been no build-up of audience involvement.

Endless Night falters on this distinction. After the funeral, Michael returns to the house and finds Greta waiting. They have until this point been constantly antagonistic, arguing vehemently in public, causing Ellie distress by pulling at her loyalties. But now, suddenly, they’re ripping each other’s clothes off and furiously having sex in the living room. A flashback reveals that they have known each other since before he met Ellie. “Uncle” Andrew has evidence of that connection, and uses it to put pressure on Michael because it casts obvious suspicion on Ellie’s “accidental” death. All of this erases the emotional investment we have placed in the romance between Michael and Ellie, but it doesn’t replace those feelings with anything of equal value. As viewers, we have until this point shared strongly in Michael’s dislike and distrust of Greta, so it’s impossible to shift gears and believe that the real passion has all along been between them.

To top it off, their moment of triumph (Ellie dead and all her wealth now in Michael’s hands) seems to last a nanosecond. The revelation that Andrew knows about them and what they’ve done turns them against each other. Greta ends up dead at the bottom of the living room swimming pool and Michael is put in that psychiatric institution where the doctors keep asking him to tell his story … which apparently changes every time he does tell it. At the end, he’s asked to start again at the beginning – and this time “try to remember what you did to Mrs. Townsend”, providing an out for all the loose ends which in retrospect don’t make sense. How is it Santonix knows that Greta is a potential danger to the couple? Why are the obnoxious family members hanging around the neighbourhood in a seemingly menacing manner?

The abrupt twist wrecks the movie. What might have fixed the problem? What if we knew early on about the plot and then watched it become complicated as Michael realizes that he does actually love Ellie? How could he untangle himself from Greta without exposing the truth and ruining the burgeoning relationship with Ellie? There are a couple of suggestive moments that point in this direction, but only in retrospect – noticing Michael watching her singing at the piano, Ellie asks why he’s looking at her like that. How? As if he loves her so much it makes him sad. And then as he’s leaving on the morning of the “accident”, he abruptly turns back and gives Ellie a passionate kiss in front of Greta – in retrospect we know that he knows that this is the last time he’ll see her alive and he’s deeply conflicted. Even if you assume the way Greta is portrayed in his narrative reflects a form of denial and rejection after the fact, the story still doesn’t really work dramatically; Gilliat hid his bomb from the audience and when it finally does go off, it creates confusion rather than revelation.

Perhaps a second viewing would provide more clues as to what is really happening, but I can’t imagine that this would compensate for the loss of what was initially so pleasurable in the film. It’s broken at the conceptual level.

Which is a pity, because it’s otherwise very well made, with fine performances and a great deal of the wit Gilliat was known for. We remain on Michael’s side for so long in good part because of his skill in dealing with his social betters (i.e. those with money and position); we root for him even past the point when we begin to understand that there’s a pathology buried in those class resentments, something hinted at in the auction scene and the visit to his mother, and finally fully exposed late in the film in a flashback which reveals that he didn’t in fact try to save a boyhood friend from drowning, but rather pushed him under so he could take the boy’s watch.

As ultimately unsatisfying as Endless Night is, as someone who long had a crush on Hayley Mills when I was very young, it was a pleasure to see her charm carried intact into this early adult role.

The film has been impeccably transferred from a 4K source for Indicator’s release, though there’s a brief section displaying some print damage. The most substantial extras are a couple of audio interviews – with Gilliat and composer Bernard Hermann, who supplied a score which recalls his sweeping work in the ’40s. There are also brief interview featurettes with Hayley Mills, composer Howard Blake (on his experience working with Hermann) and historian Neil Sinyard (on the later stages of Hermann’s career).

*

Together Endless Night and The Saga of Anatahan made for an interesting evening of viewing, but that interest ultimately resided in the films’ problematic aspects rather than straightforward satisfaction.

Comments