D.A. Pennebaker & Chris Hegedus’ Town Bloody Hall (1979):

Criterion Blu-ray review

Broadly speaking, art has an impulse towards order, while reality tends towards disorder. This is as true of documentary as much as any other creative endeavour. When cinéma vérité emerged in the late 1950s, early ’60s, new lightweight equipment allowed filmmakers to become far less obtrusive, enabling a more observational style when filming real events and activities. But the urge to become simply recorders of reality was illusory … once recorded, that reality needed to be shaped and focused and that required the intermediary consciousness of the filmmaker. The best filmmakers – the Maysles brothers, say, and D.A. Pennebaker – were skilled at shaping the material to conceal themselves and give an impression that the viewer was watching unmediated reality. This required a greater level of artistry than the more conventional documentary, which was something like a combination of reportage and information.

Inevitably, there were occasions when reality might seem intransigent, resisting the filmmaker’s art. That seems to have been the case when Pennebaker was asked to record a panel discussion at New York’s Town Hall theatre on April 30, 1971. Using three 16mm cameras (Pennebaker was joined by Jim Desmond and Mark Woodcock), the heated interactions between panel members and audience were captured with ragged immediacy, but afterwards Pennebaker was uncertain what could be done with the material. Several years later, when experimental filmmaker and artist Chris Hegedus joined his company, Pennebaker showed her the material and she set about the process of shaping the chaos into a movie. What resulted was finally released in 1979 as Town Bloody Hall. I occasionally dealt with large quantities of seemingly intractable material in my own editing career, so I can really appreciate what Hegedus managed to accomplish here; she captures the ebb and flow of a chaotic event without trying to force a narrative structure – there’s no clear conclusion drawn, what it all means is left open to interpretation, and yet it’s more than a series of moments. The personalities involved come into focus and slip back into enigma, connections are made only to dissolve again. As much as any documentary can, this one captures a brief moment in time in all its messy paradox.

The event itself had been put together by an organization called Theater for Ideas; formed by dancer Shirley Broughton in 1961, it was a well-known forum for New York intellectuals. This particular event was inspired by the recent publication of Norman Mailer’s polemic The Prisoner of Sex, which in turn had been written in response to a chapter in Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics the previous year in which the influential feminist had used Mailer as a case study in what we would now call “toxic masculinity”. Broughton proposed a public discussion between Mailer and a number of feminists, but Millett and others who were approached pointedly rejected the idea as a distraction from the more important issues they were dealing with. The event itself proved their point.

Mailer at the time was something like “the great American writer”, a larger than life figure who had managed to place himself at the centre of the upheavals of the late 1960s – particularly with his books on the anti-war movement, Armies of the Night, and the explosive political conventions of 1968, Miami and the Siege of Chicago. As Hunter S. Thompson was also doing around the same time, Mailer was in a sense creating a self-portrait which used the raw material of political and social events as a reflection of the writer. A corollary of this kind of creative work was the impression that the artist was actually the focus of all events … the writer’s ego expanded to fill all available space.

While the ostensible aim of the panel that evening was to discuss the major concerns of feminism, it inevitably became about Mailer himself. The four women who agreed (reluctantly in some cases) to participate became foils for his pontificating about life and his understanding of women’s relationship to men. Combative from the start, Mailer played the provocateur, deliberately setting himself up as a target not only for the panellists but also for the audience, thereby giving himself an opportunity to fight back as if he were the one being besieged.

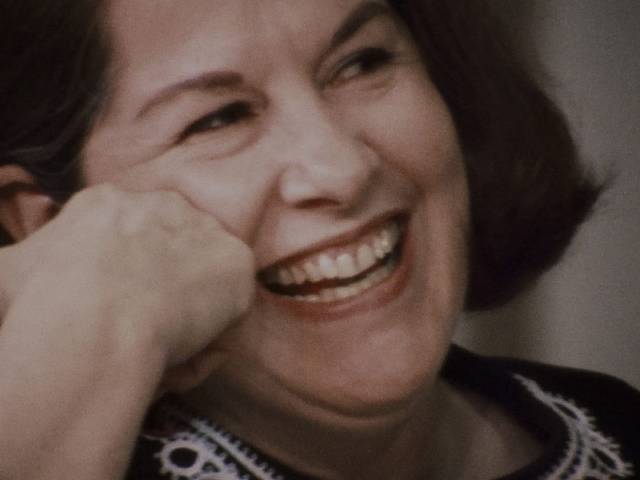

The women arrayed against him didn’t represent a unified front, but rather exemplified a multi-faceted interrogation of the status quo Mailer stood for. Jacqueline Cebellos was the head of the New York chapter of the National Organization of Women, then working to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, intent on changing the status of women by political and legislative means. Germaine Greer, in the States to promote her book The Female Eunuch, confronted Mailer as a representative of the male-centric art establishment which had historically discounted the potential of women to produce work of enduring value. Cultural critic Jill Johnson went on the attack with a lesbian polemic aimed more at what might be termed the feminist establishment rather than Mailer; at the time, the leaders of the political feminist movement tended to see radical lesbians as posing a threat to their being taken seriously by those, particularly more conservative women, whom they needed to support the movement’s political agenda. And finally, Mailer’s friend the critic Diana Trilling aimed her attack more at Greer, seemingly in support of the existing intellectual establishment of which she, along with Mailer, was a prominent part.

The differences in perspective of the four panellists reflected the fact that feminism itself, not surprisingly, was not a monolithic movement but rather a broad range of strategies aimed at dismantling age-old social and political structures and redefining women’s position within society, economically, politically, artistically and sexually. But at this event those differences continually produced fractures into which Mailer could insert himself, the alpha male, the artist who stands above and looks down at the struggles of mere mortals; the subject was feminism, but Mailer appropriated the situation to reframe questions of female identity and power (and powerlessness) in terms of the male’s experience of women, rather than women’s experience of the world. This reaches a particularly troublesome peak when he raises the issue of male violence; asserting that in an argument between a man and a woman, if the man finally hits the woman he has lost the argument, he goes on to say that if, however, the man renounces the use of violence, then that gives the woman a power which will ultimately destroy the man – apparently, barred from using violence, men will essentially explode from the internal pressure. In other words male on female violence is a matter of self-preservation. (This convoluted construction takes on an element of self-justification in light of the fact that, in 1960, Mailer stabbed his second wife twice, almost killing her.)

The audience that night, while expressing hostility towards Mailer, nonetheless seems to remain enthralled by him. The film evokes a similar reaction in the viewer: Mailer comes across as a monster of ego, and yet like so many monsters he also beguiles. He gives the impression of struggling with his own ideas, of striving to comprehend what remains incomprehensible to him (he admits at one point that he simply doesn’t understand what these women are talking about), and that struggle elicits a certain degree of sympathy even as he provokes irritation. At times it’s not clear that Mailer himself knows what he’s trying to say, or whether he’s saying things simply to be provocative – at one point he declares that fascist totalitarianism is preferable to a left totalitarianism because the latter is humourless and puts an end to intellectual life. Although one is wary of using the word, it’s impossible not to ask how much humour and intellectual vigour were displayed by the Nazis?

Hegedus edited all this ragged material (three-plus hours pared down to eighty-five minutes) into something which resembles a fascinating and engaging intellectual cage match. And that finally illuminates the futility of the event. Put on as a fundraiser for Theater for Ideas, it’s a show, a performance, a solipsistic game dominated by the self-absorbed Mailer. The film itself signals this limitation in its opening moments as audience members file in while an irate woman shouts that the whole thing and all those involved betray the poor and working class. The evening is an exercise in bourgeois intellectual navel-gazing, its very form sealing the various conflicts off from the lived reality which feminism was working so hard to change. That reality briefly rears its head a couple of times – that woman in the lobby, who reappears briefly later once again calling out that this elite indulgence is a betrayal of ordinary people’s struggles, and in an angry interruption during Cebellos’ introductory remarks when poet Gregory Corso storms out of the auditorium loudly objecting to her catalogue of women’s oppression by essentially yelling that “all lives matter” … a chilling reminder of how little attitudes have changed in five decades: white men continue to feel threatened by the idea that maybe they shouldn’t hold all the power.

If the entire event was futile and misguided (an opinion held by some of the participants themselves), Town Bloody Hall the film is terrifically entertaining, its ragged energy a reminder that there was a time when political fights weren’t simply about angrily asserting partisan certainties, when there could be honest disagreements (well, even here, some of the disagreements may have been less than honest) and even those with strongly held views were open to argument.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray has been mastered from the original 16mm reversal reels, the image – grainy and shot in available light – giving the event a visceral immediacy. It may not be pretty, but the cameras are attentive to the participants’ faces and body language, capturing the ebb and flow of humour and tension. The sound is naturally also a bit ragged, but for the most part quite intelligible (though I confess I watched it with the subtitles on).

The supplements

The disk is loaded with extras which enhance the film enormously, beginning with a commentary by Hegedus and Greer recorded in 2004. Greer reflects on her reservations about participating and her ambivalent feelings about Mailer, who at the time she was somewhat in awe of, while Hegedus speaks of the process of finding form in the chaotic material.

There’s an interview with Hegedus (25:02), newly recorded by Criterion, in which she discusses her working relationship with Pennebaker and the editing of this film in particular, and a piece about a reunion of Hegedus, Pennebaker, Greer, Cebellos and Johnston for a screening in 2004 (22:23).

There are additional interviews with Greer (12:39) and Mailer (13:44) conducted by Gerold Hofmann in 2001 for a documentary about Hegedus and Pennebaker in which both writers talk about the making of the film. Mailer had already developed a relationship with Pennebaker because he had shot Mailer’s own first three features, Wild 90 (1968), Beyond the Law (also 1968) and Maidstone (1970) – in fact, it was Mailer who got Pennebaker to come and shoot the Town Hall event, for which no permission had been obtained; the filmmakers apparently spent the evening dodging the theatre’s security staff.

The icing on the cake comes in the form of an episode of the Dick Cavett Show from 1971. While the Cavett archives have been used quite a lot by Criterion in the past, this instance is unusual because we get the entire episode (1:07:51) and it’s a remarkable piece of television very unlike what we’ve become used to on late night talk shows. It brings together three writers – Gore Vidal, Janet Flanner and Mailer. It begins with the urbane Vidal, who is then joined by Flanner, who is all wit and charm, and finally out comes Mailer to promote The Prisoner of Sex. He shakes hands with Cavett and Flanner and then pointedly ignores the hand held out by Vidal. Cavett comments on this and Mailer launches into an angry attack on Vidal who had written something critical about him. Cavett seems uncomfortable to discover that he has two guests who are apparently involved in an on-going feud and Mailer and Vidal go at each other with increasing heat until Flanner finally interjects to say that she and the audience are getting really bored with their petty dispute. Mailer then turns his attack on the audience and they in turn start attacking him. It’s all remarkably uncomfortable and yet riveting … and reveals just how vulnerable Mailer is beneath his egotistical blowhard persona.

The booklet essay is by film critic Melissa Anderson.

*

Until this release I hadn’t even heard of Town Bloody Hall, but it may well be my favourite Criterion disk of the year so far.

Comments

I recall a confrontation visually recorded between Mailer and Margaret Atwood, presumably around the same time. It’s some sort of panel discussion involving prestigious writers. Mailer is the moderator (I think). His pomposity is silenced by Atwood. She quickly destroys him.

Perhaps it was this, at the 1986 PEN Congress:

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-01-22-vw-31670-story.html