Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999): Criterion Blu-ray review

in Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999)

Beau Travail (1999), Claire Denis’ fifth feature, has haunted me for two decades. At once a film which focuses minutely on seemingly immutable physical details and yet remains utterly mysterious and enigmatic, even when one seems clearly to understand what it depicts one feels it drawing the viewer into strange emotional, psychological and spiritual depths which are so much greater than the minimal narrative appears capable of supporting. Although rather loosely adapted from Herman Melville’s posthumously published novella Billy Budd, Beau Travail is a work which could only exist on film, its images and sounds combining in ways which create an experience impossible in any other other medium.

With very little dialogue and a camera which lingers on the mundane activities of a unit of the French Foreign Legion stationed in Djibouti, where a luminous blue sea borders on a landscape of parched desert and mountains, we watch a personal tragedy unfold as perceived in the memory of the key participant, a Master Sergeant named Galoup (Denis Lavant). Adrift back in France, with nothing but time on his hands, he contemplates the events which have undone his life. That life was shaped and constrained by his tightly controlled role within the institutional structures of the Legion. He puts his men through harsh training exercises, running obstacle courses, going on long marches through the desert; he monitors their housekeeping routines – laundry, cleaning, cooking (tasks which paradoxically underline their hyper-masculine behaviour with femininity) – and watches from a slight distance as they relax in discos, dancing with local women.

But this structured life which holds any potential uncertainty at bay is disrupted with the arrival of a new recruit, Sentain (Grégoire Colin), a silent, inexpressive young man whose lack of visible affect seems to pose a challenge to Galoup. A growing sense of anger is aggravated by the fact that Sentain is liked and accepted by the other men; after he saves another man’s life when a helicopter crashes at sea, Sentain is singled out for praise by the unit’s commander, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor), with whom Galoup has had something like a friendship (they play chess together with easy familiarity). The attention Forestier begins to pay to the young soldier triggers jealousy in Galoup, who now becomes obsessed with him.

As a unit, there’s a sense of physical intimacy among the men as their training frequently brings their bodies into close contact and it increasingly becomes apparent that the antagonism Galoup feels towards Sentain is fuelled by an erotic charge. Galoup’s identity has been so tightly contained within his role as a soldier that feelings he can’t acknowledge threaten his sense of who he is and the only way he can try to restore that sense is to destroy the man who has triggered this unwanted desire.

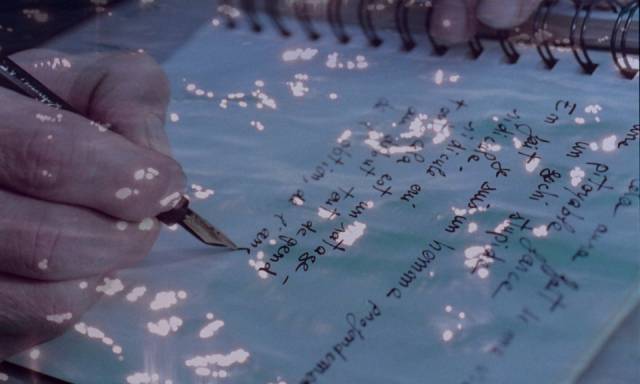

After a number of increasingly intense confrontations, Galoup gets his opportunity. Having imposed a harsh punishment on one of the other men, Galoup catches Sentain giving the man water; when Sentain is defiant, Galoup slaps him and Sentain in turn punches the Sergeant. This infraction provides ostensible justification for an even harsher punishment; Galoup drives Sentain far out into the desert and leaves him out there to find his way back on foot. This is too much – contriving to kill a soldier as punishment is a step too far, and Galoup finds himself stripped of the only identity he has, kicked out of the Legion and sent home to France, where he clings to mundane routines like carefully cleaning and ironing his clothes and making his bed military-style … and writing a journal in which he goes over the events which have led him to this dead end.

Claire Denis manages to convey all of this without conventionally dramatized scenes, but rather through oblique depictions of military ritual which take on the form of a dance full of unspoken meanings. In fact, the exercise and training routines have been literally choreographed, transforming the men’s bodies into aesthetic objects which infuse the film with an eroticism which overwhelms Galoup’s ability to repress desires he is unwilling to face. Dance is in fact used as a structuring device, with the erotic interactions in the disco reflecting the activities which fill the men’s time on the base … culminating in the remarkable final sequence in which Galoup, having lain down in uniform on his carefully made bed, rests his pistol lightly on his belly as if contemplating suicide, an implication from which there is an abrupt cut to Galoup alone in the disco. As the music begins (Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night”), his body starts to respond as if of its own accord and once it begins to move he gives in to the power it contains, explosively, violently, sensually filling the dance floor with physical ecstasy, finally releasing all the suppressed emotional and sexual energy which has been held in check during his army career. It’s a moment both exhilarating and terrifying, as if we’re seeing Galoup obliterating the only self he has ever known, opening an abyss from which there is no way of knowing what new self may emerge.

As visual poetry which conveys an ethereal subjectivity through precise and concrete imagery, Beau Travail is the equal of Tarkovsky and Malick at their best. The film dwells on male bodies at rest and in motion, boredom and mundane routines set in a landscape so vast that human activity comes to seem meaningless, opening a space where inner confusion can breed and overtake a character who until this point has escaped the need for self-reflection; and now that he must look inward, he loses himself and everything which has defined him.

*

The disk

The 4K restoration used for Criterion’s Blu-ray is stunning. Cinematographer Agnes Godard’s sensitivity to the vast desert landscape, the placid sea, and the textures of human bodies gives the film a languid yet visceral presence which the transfer evokes with great subtlety. The soundtrack, with minimal dialogue, is equally subtle in its use of ambience and, more particularly, an eclectic score which blends the music of Charles Henri De Pierrefeu and Eran Zur with selections from Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s “Shopping Cart” and, for Lavant’s climactic dance, Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night”.

The supplements

There are several excellent special features and one very problematic one. The latter is a Skype conversation between Claire Denis and filmmaker Barry Jenkins (Moonlight). This was recorded in the immediate aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and the spontaneous protests which followed, and not surprisingly these events overwhelm Jenkins, who spends a great deal of the 29:51 featurette speaking of racial inequality and social unrest in the U.S. This leaves little room for Denis to talk about her work in general and Beau Travail in particular, even when Jenkins awkwardly and rather strenuously tries to tie the film to those American issues. From the point of view of gaining an understanding of Denis’ intentions and strategies in making the film, this is one of the least satisfying extras I’ve encountered on a Criterion release, though perhaps it does serve as a reminder that in the face of real-life horror, art may not be the most important thing to focus our attention on.

The other extras are more illuminating about the film, with cinematographer Godard offering thoughts and impressions about the challenge of shooting in Djibouti and the mixture of choreography and spontaneity involved (21:33).

There’s a video essay by film scholar Judith Mayne (27:49) which explores the particular qualities of Denis’ style and also situates the film in a larger context by pointing out that Michel Subor starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le petit soldat (1963), a film about a man without any particular political convictions who becomes entangled in the messy events of France’s colonial war in Algeria. That character bears the same name as the weary officer in Beau Travail, signalling the changes which have occurred in the intervening four decades, the viciousness and urgency of the earlier war having given way to a futile presence in an Africa which has moved on from direct military oppression to a more subtle cultural colonization.

And finally there are interviews with the two stars, Denis Lavant (28:39) and Grégoire Colin (16:36), both of whom speak of the intuitive approach Claire Denis encouraged during the shoot. Lavant in particular is lively and engaging, with an impish manner and an infectious enthusiasm for what he managed to achieve in what, perhaps strangely, was his sole collaboration with Denis.

The booklet essay is by critic Girish Shambu.

Comments