Francesco Rosi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979):

Criterion Blu-ray review

Francesco Rosi, who got his start as an assistant director in the 1940s and ’50s with directors as varied as Lucino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni and Raffaello Matarazzo, began making his own films in 1952 by co-directing a feature about Garibaldi’s 19th Century campaign to unite Italy into a single nation. His solo career, beginning in 1958 with La sfida, revealed an artist with an intense interest in politics, history and the social problems of post-war Italy, a gritty examination of the intersection of power and criminality in films like Salvatore Giuliano (1962), Hands Over the City (1963), The Mattei Affair (1972), Lucky Luciano (1973) and Illustrious Corpses (1976). Most of these films were based in fact and made with a sense of urgency and outrage (he has been referred to as the most journalistic of the great Italian filmmakers).

After making Illustrious Corpses, a film rooted in the violent political unrest which swept through Italy in the ’70s, there was a three-year gap from which Rosi emerged with what seemed like a radical departure. Although Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979) is also based on real events which illuminate the connections between ordinary lives and political forces, it is set in the past and, through its gorgeous pastoral photography, at times runs the risk of evoking nostalgia as if the ugliness of the present makes the ugliness of the past appealing. And yet the careful attention to detail and the subtle emotional currents running through the film somehow save it from the dangers of aestheticizing poverty. In this, it shares a kinship with Ermanno Olmi’s exquisite The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978), another film accused of romanticizing the poor.

Based on a memoir by Carlo Levi, Christ Stopped at Eboli is a slow, contemplative work made in four parts for RAI television – at 222 minutes, it follows the slow rhythms of life in a peasant community in the mid-’30s. There was a 150-minute theatrical version, but it’s hard to imagine that kind of compression not severely damaging the film. Levi, an intellectual from Turin in the North, was arrested by the Fascist regime for his anti-Fascist activities, but apparently there wasn’t sufficient evidence to imprison him; instead, he was sent into internal exile (a practice dating back to the Roman Empire), separated from his normal life and placed in a remote, impoverished region in the South where his movements were restricted, his mail monitored by the local authorities, and he was required to report to the police every day. There were other exiles in the town, but they were all forbidden to mingle with one another.

Interestingly, Rosi begins the film with a strategy similar to the one used by Andrei Tarkovsky in both Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979); we follow Levi on his journey to the village of Gagliano, which involves two trains, a bus full of peasants and chickens, and finally the only private car in the area. This journey takes up almost the first twenty minutes of the film, with Levi (Gian Maria Volontè) observing the changing faces of his fellow passengers and the landscape through which he moves, with a sense that he’s virtually travelling back in time. But as in Tarkovsky’s films, this movement seems less physical than conceptual, the combination of stillness (the character sits in a series of vehicles) and movement serving to adjust the viewer’s own way of seeing, slowing attention and focusing on seemingly incidental details which come to form the substance of a film which isn’t concerned with plot or incident so much as with perception and a subjective experience of the viscerally physical world.

The chief difference between Tarkovsky’s films and Rosi’s is that the former establish a world from which the characters travel to a new setting, while the latter (after a brief prologue with an older Levi thinking back, establishing what we are about to see as a memory) begins with the journey and we only come to understand the world he’s coming from as fragments are gradually revealed during the course of his exile.

When Levi arrives in Gagliano, he’s disconnected, alienated. He feels no relationship with this primitive place which seems to have been passed by as the rest of Italy has modernized. He’s placed in the house of a widow, sleeping in a room with several beds which are occasionally used by others who visit the town on business. He spends his days wandering the streets, witnessing poverty and sickness (the area is plagued by malaria), approached by the wealthier citizens who recognize his superior social position – and who frequently warn him about others whom he should avoid. Despite being so isolated from the rest of the country, there are petty bureaucrats who take pride in being even a minor part of Mussolini’s grand plan to restore the greatness of the long-lost Empire, starting with a brutal war against Ethiopia which Il Duce is determined to annex so that Italy’s poor will have land in which to expand and flourish.

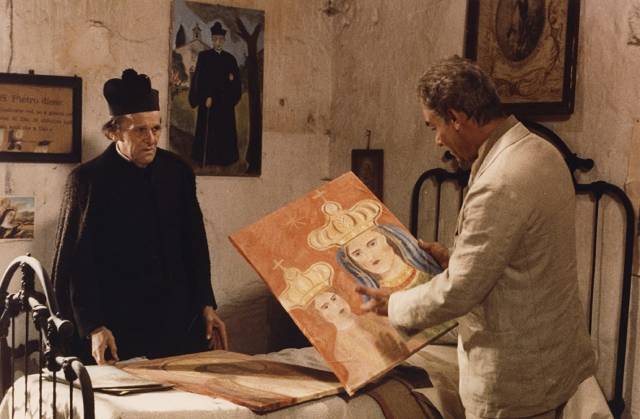

Things begin to change when rumours spread that Levi is a doctor and people start to flock to him for help and medical advice because no one trusts the town’s two older doctors. There’s a tension between the practice of modern medicine and deeply rooted superstition – the peasants believe in witches and curses – and yet this new young stranger inspires faith in them. True, Levi studied medicine and got a degree, but as he insistently tells those who approach him for help he has never practised and can’t do anything for them. He’s a writer and painter, a man who stands at a slight distance and observes. And yet against his own inclinations, the insistence of petitioners draws him in and he does begin to offer medical advice … something which later causes him some trouble as the authorities try to bar him from practising medicine.

Across the four episodes, almost invisibly, the outsider becomes part of the community, a middle-class intellectual who is moved by the poverty and hardship which surrounds him. This is presented not as a political transformation, but rather as an individual and emotional awakening. And it emerges as a subtle undercurrent which gradually swells beneath a leisurely series of essentially anecdotal scenes involving a progression of characters with whom he engages – the widow with whom he first stays; the mayor (Paolo Bonacelli), a proud Fascist who nonetheless admires and respects Levi; the woman who comes to clean the house he eventually rents (Irene Papas) and her young son; the local priest (François Simon), himself an exile and a bitter alcoholic. The village children are frequently seen running like a pack of feral animals, throwing rocks at the priest and Levi, but near the end, they crowd into his house for painting lessons.

A key element in Levi’s transformation comes with a visit by his sister Luisa (Lea Massari), herself a doctor, who helps him to begin engaging with the peasants rather than simply observing them. By the time Levi receives amnesty, along with all the other exiles except two young Communists, he feels an urgent need to find a way to solve the “problem of the South”, the way in which a large region of Italy had been ignored in the modernization begun by Garibaldi’s unification in the mid-19th Century, and still being ignored almost a hundred years later because all that unification and modernization was in the hands of intellectuals and politicians from the North who could barely muster a basic awareness of the lives led by peasants. When Levi returned from his exile, he was faced with this lack of awareness as he re-engaged with other leftists trying to bring Italy out of its Fascist era.

It’s in the final scenes that Rosi shifts from the subtle observational style of the film to a more didactic mode, with Levi discussing the issues he’s become aware of with other activist intellectuals who look at the problems from a theoretical (and somewhat condescending) position. It becomes clear that, since his personal experiences in Gagliano, he no longer speaks the same language as these colleagues and that gap indicates that real social change will be a long and difficult project.

Christ Stopped at Eboli is beautifully shot by Pasqualino De Santis, with Rosi composing shots with a combination of seeming simplicity and expressive precision. While the performances are uniformly excellent, with many in the cast non-professionals, the entire film is anchored by Volontè, who gives a remarkable performance – for much of the film, he provides a still point of focus; we see this world through his eyes and with the subtlety of his expressions he guides our understanding of what we see. A versatile actor capable of projecting energy and violence (immediately after this he starred as a Basque separatist involved in an assassination in Gillo Pontecorvo’s Ogro [1979]), here he gives us a rich sense of inwardness, of thought and evolving understanding.

As in Tarkovsky’s films, Rosi seems to guide viewer perception in complex yet unequivocal ways; we emerge from the film with the feeling that we have lived in this place and come to know its people intimately. Like Tarkovsky’s Mirror, it gives us a sense of the flow of time which is rooted in a particular place through which natural, social and political currents flow. Within that flow, individual details stand out to provide markers which keep us oriented. One, a seeming non sequitur, is the dog Levi encounters when he gets off the first train on his initial journey; sitting patiently on the platform, it has a tag on its collar announcing its name as Barone and asking someone to take care of it. The dog follows him onto the next train, then the bus – when it attacks a chicken held by one of the other passengers, who demands to know to whom it belongs, Levi asks one of his police escorts if he can keep it, and from then on it remains a calm, seemingly happy companion, as if it were a kind of spirit guide showing him the wisdom of taking an interest in every detail of the world around him.

Christ Stopped at Eboli seems to have marked a shift in Rosi’s work, away from the aggressive engagement with contemporary issues towards something more personal and internal – it was followed by Three Brothers (1981), a version of Bizet’s Carmen (1984), and an adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987). If it reflected something of a retreat from the complications of contemporary Italy, with its extremes of corruption and violence, it is nonetheless one of the most emotionally resonant and aesthetically rewarding films Rosi ever made.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray was mastered from a 2K scan of the original 35mm camera negative and the image, while showing some occasional minor damage, is visually rich with saturated colours, the sunlit landscapes contrasting with small, often quite dark interiors. Sound is clear, dialogue natural, with subtle support from an unobtrusive score by Piero Piccioni.

The supplements

There are four substantial extras, beginning with an informative talk by Michael F. Moore (27:28) who did the subtitle translation and discusses the film from the point of view of a translator and interpreter who has worked closely with Rosi.

There are two pieces from French television, Reflections on a Political Cinema (1978, 24:39) and Bad Earth (1974, 26:45). The former contains some behind-the-scenes material from the production in a larger context in which Rosi and Elio Petri are interviewed about the state of Italian cinema at the time. The latter brings together Rosi and Carlo Levi to discuss the painter’s experiences and the book which came out of his period of exile, as well as the connection the two men had dating back to the early ’60s when Levi visited Rosi while he was shooting Salvatore Giuliano.

In addition, there’s a brief excerpt (13:09) from a documentary in which Rosi talks about working with Volontè on five features over two decades.

There’s a trailer (1:48), and the booklet essay by Alexander Stille provides some useful background on Levi’s life and the way Rosi adapted his story to film.

Comments