Euro Horror

Trying to play catch-up with this blog has always been a futile prospect, though I did manage a bit better during the Covid lockdown as I could devote some time every day to writing – but now that I’m back at work full-time, that’s just not possible. So once again, the pile of watched disks beside my desk is growing larger (three-dozen and counting as I write this) and it feels kind of pointless trying to say a few words about everything. So some movies have been relegated to the overloaded shelves with never a word said, while others nag at me until I feel compelled to write another “brief comments” post.

As always there’s no coherence, so I’ll start with a couple of directors with several titles each in the pile – and needless to say, horror dominates.

*

Dick Maas

Dutch filmmaker Dick Maas came along half a generation after Paul Verhoeven, but unlike his more famous countryman, he didn’t start out by making “art films”; he aimed directly at a commercial market. And yet, oddly, despite the technical polish of his genre films, he never made a successful transition to Hollywood – he eventually did a few television episodes and a couple of features in the States, but mostly stayed in the Netherlands. Over the years he frequently switched between comedies and horror films, sometimes mixing the two. I haven’t seen any of the comedies, but the horror movies I’ve seen are reasonably effective, with the elements of comedy usually sufficiently kept in check so that they don’t undermine the horror.

I haven’t seen any of his movies, but of the three I recently watched, two were films I’d seen before, while the third is an American remake of one of the Dutch movies, a la George Sluizer’s The Vanishing (1993).

De Lift (The Lift, 1983)

De Lift (The Lift, 1983) is an effective thriller which takes a patently ridiculous idea and plays it relatively straight, making it an appealing B-movie which belies its limited budget. In fact, one of Maas’ distinguishing characteristics is the way he makes the most out of his resources – he eventually established his own studio, marking him as a business-minded filmmaker rather than an auteur. He generally maintained control of his work by writing, producing, directing and even composing the scores himself.

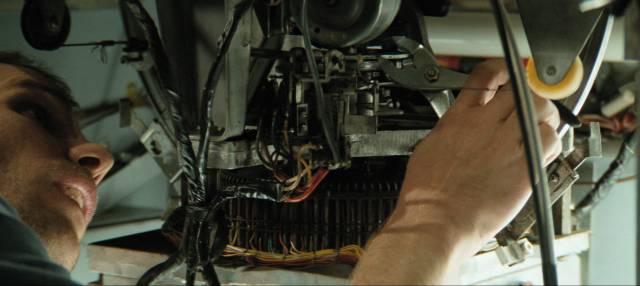

The protagonist of De Lift, Felix Adelaar (Huub Stapel), is an elevator repairman who is responsible for a new building, having been assigned after another company employee committed suicide. There are inexplicable malfunctions which quickly go from stranding passengers for hours to killing people who work in the building. Felix realizes there’s something more than mechanical problems involved, as does reporter Mieke de Beer (Willeke van Ammelrooy), who latches on to him as he digs into the history of the shady company which designed and installed the lift’s control system.

It turns out that that system evolved from military experiments with organic computer chips and now the lift’s “brain” is growing and becoming sentient, its military origins making it hostile to human beings. Maas does a good job mixing horror and mystery, while keeping things light with engaging characters.

Down (2001)

All those low budget advantages get lost in the American remake, Down (2001). Bigger, longer, with a name cast – most notably Naomi Watts as reporter Jennifer Evans just before she hit it big in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001). (The other incidental Lynch connections are James Marshall appearing as elevator repairman Mark Newman a decade after his Twin Peaks tenure as James Hurley, and Dan Hedaya, who had a small role in Mulholland Drive.) But as is often the case, bigger is definitely not better. Maybe it’s because Maas was working in English and in a country very different from his own, but the balance of horror and comedy is off in the remake and the two leads lack the personal charm of their Dutch predecessors. The English-language version seems strained and awkward, its A budget weighing down the B-movie material.

Amsterdamned (1988)

After the original De Lift, Maas made a comedy called Flodder (1986) which eventually turned into a franchise with several sequels and a TV series. That was followed by Amsterdamned (1988), a fairly successful attempt at a Northern giallo. Although, as in more than a few genuine gialli, the ultimate resolution of the mystery is disappointing, what Amsterdamned has in abundance is atmosphere, with Maas making excellent use of the Dutch capital with its many canals. The killer prowling the city uses scuba gear to get around, striking from the water. The mask and black gloves of the traditional giallo killer here become a full-body wet suit which makes the first eye-witness (a homeless woman) declare that the victim was attacked by a monster with claws.

Like some of the later Italian gialli, Maas’ film blends the fetishistic series of murders with a police investigation, the lead character being a divorced detective; Eric Visser (Huub Stapel again) is not the most attentive father to his adolescent daughter, who inevitably ends up in danger from the killer. Visser also juggles the demands of the case and its escalating body count with the possibility of a new romance with Laura (Monique van de Ven), a diving enthusiast he meets during the investigation, who is also a bit closer to the killer than she realizes.

While the mystery itself is pretty perfunctory, its resolution feeling more than a little arbitrary, Maas concentrates on the set-pieces – the POV stalking scenes leading to each killing; the disturbing revelation of the first victim’s body hanging beneath a bridge and dragging bloodily along the glass top of a tourist boat; and most spectacularly a high-speed boat chase along the canals, which Maas packs with dangerous-looking bits of business. Even though the film doesn’t quite deliver on its narrative promise, this sequence alone guaranteed its commercial success.

All three movies were released by Blue Underground in dual-format editions, with fine 2K transfers. Each gets a commentary (Maas with editor Hans van Dongen on De Lift and Amsterdamned, and with stunt coordinator Willem de Beukelaer on Down), a making-of featurette and various interviews.

*

Lucio Fulci

Lucio Fulci has grown in stature over the past couple of decades. I know I was really critical of his work when I first saw movies like Zombi 2 (1979) and City of the Living Dead (1980) in their original theatrical runs. That low opinion has changed as I’ve seen more of his films, and re-watched many of them multiple times on video. Probably the biggest factors in my own re-evaluation were seeing The Beyond (1981) and Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), which I consider his two best in the genres he’s most noted for – horror and the giallo. I haven’t seen his early comedies, but his spaghetti westerns, Massacre Time (1966) and Four of the Apocalypse (1975), are very good. However, his strongest work remains the gialli and horror movies he made between One on Top of the Other (1969) and New York Ripper (1982).

There are a number of reasons why his work became more erratic in his final decade, not least various health problems that made it more difficult for him to take on projects. But there were also significant changes in the Italian industry, particularly the decline of interest in the horror genre which resulted in reduced budgets – with fewer resources and constricted schedules, his work became more perfunctory, stories more padded and effects less effective. And yet, with my rising opinion of the major films, I’ve found my interest in and enjoyment of some of the later work also increasing.

Cat in the Brain (1990)

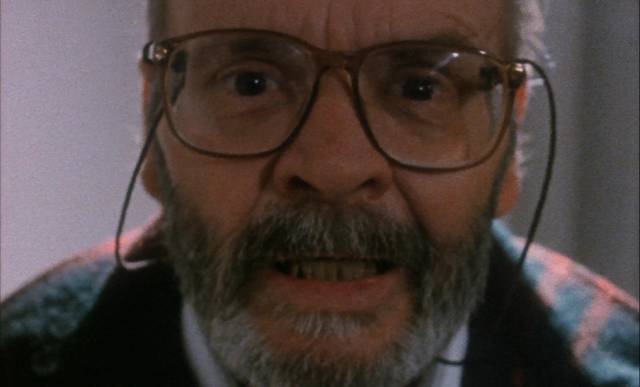

I recently watched Cat in the Brain (1990) for the first time, a movie which seems never to have been highly regarded, even among Fulci fans. Yet I found it fascinating and very entertaining. The filmmaker’s most self-referential movie, it appears on the surface to be a lazy attempt to squeeze a little more mileage out of two equally poorly regarded low-budget made-for-television features, Touch of Death and Sodoma’s Ghost (both 1988), as well as five movies by other directors made for an un-aired series called Lucio Fulci Presents. Much of Cat in the Brain consists of large chunks lifted intact from those movies, all given a new frame in which Fulci plays a version of himself, a famous director of horror movies who’s working on a new project while slowly going crazy, hallucinating various horrors which echo his work (the scenes from those earlier movies).

Cat in the Brain conveys both a self-deprecating attitude towards Fulci’s reputation as a purveyor of gratuitous gore and an underlying irritation at the idea that that’s all he is. The film revels in its cheap and often unconvincing effects while nonetheless providing a wry and engaging self-portrait. Fulci often appeared in small roles in his films, usually as a doctor or a cop, but here he ably carries the film with a performance which makes him really likeable.

The Grindhouse Limited Edition Blu-ray makes the most of the less-than-stellar source materials, adds a second Blu-ray containing almost five hours of interviews and other ephemera, plus a CD soundtrack … that excess just adds to the wry humour of the slightly shabby feature itself.

Touch of Death (1988)

I experienced a confusing sense of deja vu when a friend lent me Fulci’s Touch of Death not long after I’d watched Cat in the Brain because so much of the latter came from the former, though I didn’t immediately realize it – seeing the relevant scenes in their original context was disorienting. I actually preferred those scenes in their later context, because Touch of Death itself is a sour attempt at horror comedy in which a serial-killer cannibal robs, kills and disposes of a succession of widows, the joke apparently being that they’re all ugly and annoying which supposedly makes his cheerfully committed violence pretty funny.

Aenigma (1987)

Much better (relatively speaking) are a couple of late features given 4K restorations by Severin and released in a bundle along with Simone Scafidi’s biographical documentary Fulci for Fake (2019). The features, Aenigma (1987) and Demonia (1990), are pale echoes of Fulci’s best work, but both are fairly entertaining in a slightly threadbare way, and both refer back as much to other directors’ work as they do to Fulci’s own. There are multiple sources for Aenigma, not least Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) and Phenomena (1985), Richard Franklin’s Patrick (1978) and Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976); while Demonia owes something to Michele Soavi’s The Church (1989), with perhaps a touch of Mike Newell’s The Awakening (1980) and Fulci’s own Manhattan Baby (1982).

Although narrative coherence had never been one of Fulci’s strong points, Aenigma seems particularly random. In a prologue, Kathy (Milijana Zirojevic), a shy student at a private school in Boston (looking very much like Serbia), is set up by her seemingly friendly roommate; a date with the hunky gym teacher leads to public humiliation … running from the scene, she is chased by the other students in their cars and runs out onto the highway, getting hit by a passing vehicle and ending up in a coma. Her replacement is transfer student Eva (Lara Lamberti), who seems oddly affected when she steps out of the taxi which drops her at the school’s front door.

The script never manages to clarify what’s going on – at moments it seems that Eva has been possessed by the spirit of the unconscious Kathy, at other times that Kathy’s spirit (a la Patrick) is telekinetically attacking the people responsible for the devastating prank which put her in a coma. But then there’s also the lurking presence of Kathy’s peasant mother (Dusica Zegarac), the school’s housekeeper who is surrounded by an aura of superstition as she watches the girls getting picked off in bizarre ways (including one who’s smothered to death in bed by hundreds of large snails in a nod to Argento’s maggots in Suspiria and swarming bugs in Phenomena).

Adding to the creepiness in a non-supernatural way, various male authority figures display a predatory sexual attitude to the school girls – not just the gym teacher who participates in the humiliating prank, but also Kathy’s doctor (Jared Martin) who wastes no time hitting on Eva. Although Aenigma has a strong odour of deja vu, and the set-piece killings aren’t as fully developed as they might have been earlier in Fulci’s career, it is nonetheless fairly entertaining.

Demonia (1990)

Demonia feels a bit more padded, but it does manage some interesting variations on familiar horror formulas. In contrast to the gloomy Gothic mood of Aenigma, much of it is shot in bright Mediterranean sunshine. In the film’s most effective sequence, the prologue depicts a mob of angry Medieval villagers brutally killing a group of nuns. As in Soavi’s The Church, it’s ill-defined which party is evil here – what horrors the nuns have supposedly committed to warrant being nailed to crosses and then burned alive isn’t specified. But whatever the evil is it reaches across time because we jump from this horror to a room in Toronto where archaeology student Lisa Harris (Meg Register) is attending a seance and almost passes out when she receives a vision of the nuns being killed.

Meg’s mentor, Professor Paul Evans (Brett Halsey), disparages her dabbling in the occult, insisting on a strictly rational attitude to the science of history. In fact, he actively dislikes certain periods because of their irrationality – particularly the Dark Ages – preferring the supposedly much sunnier and more enlightened culture of Classical Greece. Soon after her disturbing experience, Meg joins a group of students under Evans’ supervision on a field trip to southern Sicily, where the locals are hostile to the idea of disturbing the ancient ruins. They have good reason for their attitude, having been descended from the villagers who killed the nuns beneath a monastery which looms on the hilltop above the ruins being investigated by the students.

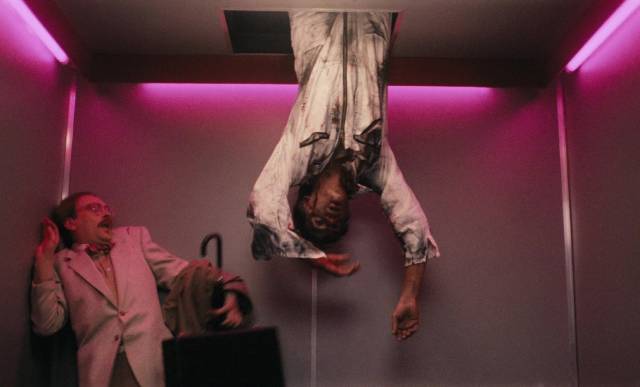

Although Evans continually nags her, Meg is strongly drawn to the old monastery and while poking around inside is compelled to break through a wall in the cellar where she finds a sealed room with the mummified corpses of the nuns still hanging from their crosses. Needless to say, her intrusion unleashes an evil force and the ghostly nuns begin to kill members of the team. The peak of their activities has one of the team strung upside down between two trees and booby-trapped so that when his young son approaches and triggers a tripwire, the little boy watches in horror as his dad is torn in half by the trees.

Even though Demonia looks more polished than the made-for-TV movies Fulci had been making in the previous couple of years, and the Sicilian locations give it some sense of scale, the low budget leads to a fair amount of padding and unconvincing effects (the death by tree is more impressive in conception than execution). The prologue and some decent performances, however, mark it as a late work which does no real disservice to Fulci’s legacy.

Both films were scanned in 4K from the original negative, so despite some minor damage and the limitations of low budgets, they look pretty good on Severin’s Blu-rays. Both English and Italian dubs are included, and each film gets a commentary and assorted featurettes – deluxe treatment for what amount to minor footnotes to Fulci’s career. There’s also an Aenigma soundtrack CD.

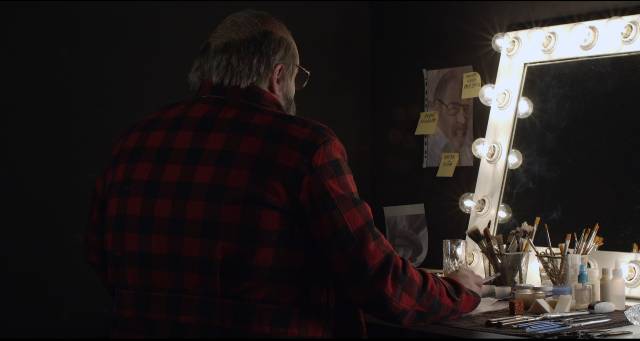

Fulci for Fake (Simone Scafidi, 2019)

Giving more context to these movies, Simone Scafidi’s biographical documentary Fulci for Fake (the title is a clumsy reference to Orson Welles’ playful pseudo-documentary F for Fake [1972]) focuses more on the filmmaker’s life than a detailed account of his films. This may disappoint some viewers, but it does serve to humanize a director with a reputation for being difficult and abusive, not to mention accusations of misogyny – though the violence on display in his films is meted out to men and women alike, indicating misanthropy more than misogyny.

The documentary is at times a bit clumsy, not least in its use of the rather self-conscious structuring device of having actor Nicola Nocella interviewing people about Fulci in preparation for playing the filmmaker in a biopic. This suggests that Fulci himself was playing a character in his own life, never to be fully understood even as the interviews delve into his experiences and motivations. I can’t say that it worked for me, but it was possible to ignore the gimmick much of the time and focus on the interviews themselves, which do provide a lot of information and insight into Fulci.

While many of Fulci’s collaborators get their say – writers, actors, cinematographers, producers – the heart of the film is a deeply moving interview with his daughter Camilla, supplemented later by her sister Antonella who has appeared more frequently on previous disks. From Camilla, we get many painful details which affected Fulci and his work, from a childhood riding accident which broke her spine, leaving her crippled, to the suicide of her mother in 1969. Camilla’s injury found its way into her father’s work most visibly in New York Ripper as the motivating force for the killer’s crimes. As for the suicide of Fulci’s wife, surely it was no coincidence that 1969 marked his decisive shift from comedies to darker and more violent movies.

The interviews with Fulci’s daughters are passionate and protective, while those with his collaborators acknowledge sometimes difficult working relationships but express genuine appreciation for his creative abilities. Archival material, including old home movies and family photographs, brings Fulci into sharper focus and adds to a growing appreciation of his work – even the weaker features of his final decade.

Severin’s Blu-ray presents the digitally-shot feature as well as you’d expect. The disk is stacked with four hours of extras, mostly additional interview material which didn’t fit into the final cut. Most significant is the complete session with Camilla (1:12:32), which was apparently the only interview she ever gave before her death last year. There’s also a collection of home movies accompanied by audio from interviews with Fulci conducted by the director’s biographer Michele Romagnoli, who gives an additional interview about his relationship with the filmmaker.

Sometimes the more you know about an artist the more problematic their work becomes; but sometimes learning more engenders a greater appreciation for work which had initially seemed problematic. For me, the latter is true in Fulci’s case.

Comments