World Cinema Project 3: Criterion Blu-ray review

Growing up in England and, after I turned 12, in Newfoundland, my early movie experiences were unexceptional. I recall Pinocchio, Zulu, Whistle Down the Wind, Ben Hur, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines… Probably the most exotic thing I saw back then was M. Hulot’s Holiday when I was five or six. Although there might be occasional foreign movies on television and, later in my teens, in one of the three theatres in St. John’s, things didn’t really open up until I moved to Winnipeg in the summer of 1973. One of the first films I saw, at the Park Theatre, which specialized in foreign and independent films, was Claude Chabrol’s Le Boucher and I wasn’t quite sure what to make of its low key, oblique storytelling. In fact, I wondered why it was getting such good reviews – it was many years later, when I saw it again on video, that I realized how good it is.

Through the rest of the 1970s my experience expanded. Not only was the mainstream undergoing some radical changes in the wake of the collapse of the Production Code and the rise of independent producers; there was a growing market for foreign films, although these tended to be relatively accessible titles, drawn from familiar cultural sources – French, German, Italian. Japanese films were the most different from my own experience.

My real awakening came when I attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 1981, where I saw fifty-six movies in sixteen days which not only included mainstream titles like Harold Becker’s The Black Marble and Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing, but also opened up my experience of national cinemas I thought I knew fairly well. It was there that I first encountered the work of Alexander Kluge (Die Patriotin), Margarethe von Trotta (Schwestern oder Die Balance des Glücks) and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg (Hitler, ein Film aus Deutschland).

There were movies from Hong Kong, of course, by filmmakers I would eventually become more familiar with, and from China and Japan; but also from Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Turkey, India, Pakistan; from Cuba and Brazil; from Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, Denmark and the Netherlands. Seeing such a wide variety of films from so many different sources called into question deeply ingrained ideas about what a film should be – both on a technical level and in terms of how stories could and ought to be told. But most of all, many of these films confronted me with the narrowness of my own cultural perspective; I couldn’t be certain that I understood what I was watching because I was unfamiliar with the cultural codes shaping not only the behaviour of characters but also the narrative choices of the filmmakers. I had to recognize that I had an innate tendency to appreciate more those movies which aligned to a greater degree with my prior experience and understanding while nonetheless stretching those boundaries.

My experience of cinema has continued along these lines in the ensuing decades, my appreciation of initially confusing work growing with increasing exposure – from the start, it was easy to embrace the films of Abbas Kiarostami (but then he was accused by Iranian critics of tailoring his work to Western audiences), while to some degree Sergei Paradjanov still confounds me; I was completely lost by Miklos Jancso’s extremely abstract Hungarian Rhapsody and Allegro Barbaro, but eventually gained a vivid sense of Hungarian historical conflicts from My Way Home and The Round-Up. This is a process which has no definitive ending because I can never fully know or understand other national cultures, though I seldom feel as intimidated now as I did when I was younger, perhaps because it’s easier to accept my limitations while also having a much broader experience of cinema outside the Western mainstream; these days I have more patience with things I don’t immediately understand.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that I can still be surprised and (hopefully) enlightened by encounters with unfamiliar work such as the six features in Criterion’s third set of movies restored by the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, which began its on-going effort to preserve movies which might otherwise vanish through neglect in 2007. As with the previous two sets, this volume is a sampler of titles from multiple countries and periods, many of which haven’t previously received wide distribution outside of their own borders. This means that there is no particular curatorial idea shaping the set, which in itself runs the risk of seeming to make of the films representative samples of what are surely very diverse national cinemas. Packaged together like this, one may fall into the trap of seeing each film not as an individual, idiosyncratic work of art but rather as a component of some educational project extrinsic to the films themselves.

This risk is increased by the need to watch them all in a short period in order to produce a review. I’m aware that I may do a disservice to some of them because they didn’t immediately provide as satisfying an experience as others – because of the variety, it’s unfair to make comparisons and yet it’s also very difficult to resist that temptation; their enforced proximity creates a false context which amplifies the tendency to view newly encountered films through filters which have been developed over a long personal history of movie watching.

I must pause here to contemplate the source of so much excuse-making; I have no doubt that it’s rooted in those feelings of uncertainty about my ability to comprehend something not already connected to what is familiar. Any one of these films on its own probably wouldn’t have prompted such insecurity, but six packaged together reminds me of how much I still don’t know and pushes me to find connections and parallels where none really exists.

With all that said, it’s time to address each film and try to sort out my impressions.

*

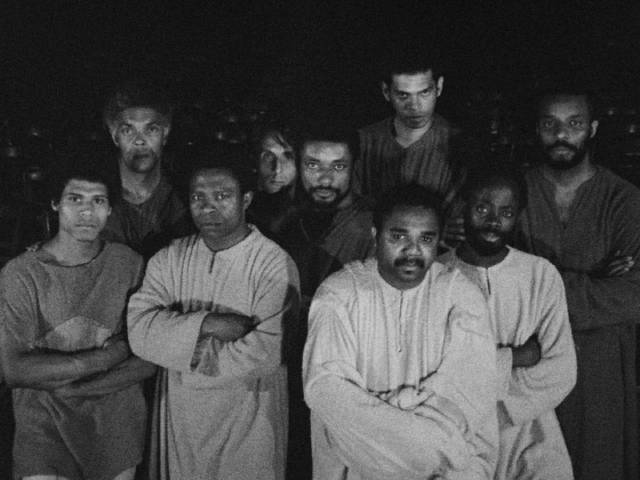

Pixote (Héctor Babenco, 1981)

I’ll begin with the only film in the set that I’d previously seen. Unlike the others, Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (1981) was widely distributed outside of its country of origin, Brazil, winning numerous awards. I saw it twice during its theatrical run in Winnipeg in 1981. Although the specific details of its depiction of grim social realities might not have been familiar, its form was. Babenco used techniques long known from neorealism to tell the story of street kids in Brazil’s huge cities. Although most if the adult roles went to professionals, the kids came from the streets, portraying on-screen versions of themselves with sometimes harrowing authenticity, none more than thirteen-year-old Fernando Ramos da Silva as the ten-year-old Pixote.

These kids, living in slums, uneducated, fall naturally into petty crime and find themselves swept up in periodic police raids. Although the reformatory they’re sent to is presented by the authorities as an almost nurturing place, providing a substitute family, it is in fact brutal and corrupt. Rapes and beatings bring down the wrath of the men in charge because their own reputations are threatened. Police abuse the kids to get information about unsolved crimes – it doesn’t matter whether the information is accurate or not, whether actual perpetrators are arrested. And in the darkest moments, the cops carry kids away in the night and execute them on the outskirts of the city.

In the midst of these horrors, some of the kids form emotional bonds which help them at least for a while to survive. While sex inside the reformatory may be used as a means of exerting power and control, it can also be an expression of love and attachment … an expression accepted by the boys who, all caught in the same brutal circumstances, recognize the need for emotional support. In retrospect, one of the boys, Lilica (Jorge Juliao), can now be recognized as transgender (at the time he seemed rather flamboyantly gay) but no one questions his openly loving relationship with Dito (Gilberto Maura) – no one other than figures of authority who use slurs as yet one more tool to humiliate and control the boys.

Pixote and a number of others manage to escape and make their way back to the streets, where they survive by picking pockets and stealing purses. Because they are all underage, they are useful to experienced criminals, who use them to deal drugs. But being kids, they are easily exploited and cheated. It doesn’t take long for them to become hardened and violent – Pixote eventually kills a woman who has robbed him and his companions, an act which gives him a momentary shock but seems mostly to reinforce the trauma which has already numbed him.

In fact, it’s a brief period of emotional closeness which proves more traumatic as he and one of his friends move in with a weary prostitute named Sueli (Marilia Pera), who enlists them to prey on her customers – an alliance which leads to yet another tragedy, following which Sueli offers Pixote a moment of maternal comfort, only to react in horror at her own feelings and the emotional vulnerability they bring with them. The harsh life they briefly share has no room for such attachments and she drives him away.

Pixote is an incredibly harsh film, unflinching in its depiction of lives caught up in a brutal society which views these kids as nothing; and yet in getting so close to them, Babenco reveals rich and complex lives forged in reaction to the brutality. We see it all through the incredibly expressive, watchful eyes of Fernando Ramos da Silva, himself a child of the slums, whose actual life reflected that of the boy in the film, ending abruptly when, at nineteen, he was shot to death by the police.

*

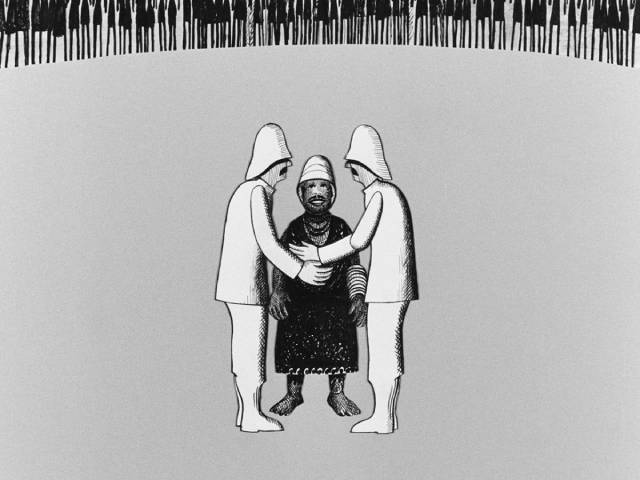

Soleil Ô (Med Hondo, 1970)

If Pixote conforms to a recognizable cinematic category, Med Hondo’s Soleil Ô (1970) mixes multiple forms – documentary, drama, even animation – to break free of audience preconceptions and insist on a perspective not borrowed from Western filmmakers. Polemical and satiric, infused with anger, it depicts the consequences of European colonialism from the point of view of the colonized, determined to assert an identity not imposed from outside. In a prologue which combines animation and slapstick borrowed from silent cinema, Hondo quickly sketches in the colonial view of Africans as less-than, as commodities in a colonial economy, before arriving in contemporary Paris with Robert Liensol, a man possessed of both dignity and an easy humour.

In a mixture of dramatized scenes and cinema verite shot on Parisian streets, we are presented with the emotional toll of racism on a man who is educated and articulate yet viewed with fear and contempt by French people who have no innate claim to superiority yet possess an easy assumption that Liensol can’t be trusted and isn’t worthy. He’s turned away from jobs with no attempt made to conceal the fact that it’s because he’s Black. He becomes involved with politically active immigrants, trying to assert their right to be a part of a French society which had long benefited from its exploitation of people under its colonial rule.

Hondo undermines the simple dichotomies of racial attitudes by including people of mixed race who are assumed by the French to be white, causing surprise and awkward embarrassment when their actual identities become apparent. There’s a startling sequence, shot with a hidden camera, as Liensol and a white woman embrace and kiss on a street as passers-by stare in disbelief and distaste.

While Hondo uses multiple techniques, the film is unified by its sense of anger about the injustice of colonialism and the racism fueling a political and economic system which can only exist by repressing and dehumanizing its victims. It’s a mark of Hondo’s skills that this first feature is both stylistically complex and playful, embodying in its form an irrefutable repudiation of the attitudes it is critiquing.

*

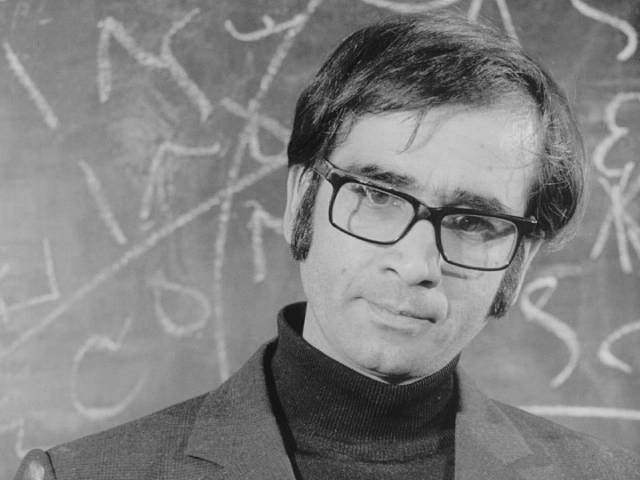

Downpour (Bahram Beyzaie, 1972)

Bahram Beyzaie’s Downpour (1972) proved to be the most frustrating film in the set, but not for reasons intrinsic to the film itself – rather, my irritation stemmed from a technical decision on Criterion’s part. There is only a single known print of the film in existence, the director’s personal copy, and it has burned-in English subtitles. However, these subtitles have frequent gaps where dialogue remains untranslated, and where they do exist they are often misplaced so you read a line which applies to something a previous character has said. This leaves the viewer straining to make sense of what is going on. Given that there is plenty of space in the frame below the burned-in text, it should have been an easy task to provide new, accurately translated optional subtitles. Any resulting clutter would have been a mild inconvenience compared to the experience of watching the film as it now exists.

That aside, Downpour is recognizable as a precursor to the New Iranian Cinema, made just a year before Kiarostami made his own first feature. Beyzaie was determined to go counter to the artificiality of Iranian entertainment by focusing on the lives of ordinary people, combining observation of a particular community with a low key comedy of character. I must admit that my sense of Iran derives largely from the films of Kiarostami, and to a lesser degree some of the work of Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Jafar Panahi, so I found myself viewing the community in Downpour through that pre-existing lens. This resulted in seeing the characters as characters, being performed rather than simply observed in the course of lives being lived – no doubt unfair and inaccurate.

Hekmati (Parviz Fanizadeh), a young unmarried teacher, arrives in a community to take up a position in the local school. In the opening scenes, he seems naive and clumsy (he breaks a large mirror and an heirloom lamp as he unloads the cart carrying his possessions; the significance of this is explained by Beyzaie in an interview on the disk), and his inexperience in the classroom shows in the unruliness of the children. When he kicks one boy out of the class, he finds himself confronted by the boy’s irate sister, Ati (Parvaneh Massoumi). An unmarried seamstress, Ati is resisting pressure to marry the local big shot Rahim (Manuchehr Farid). When the boys in the class start a rumour that Hekmati is in love with Ati, he finds himself in an awkward position – as a single man, he needs to maintain respectability. When Rahim gets wind of the rumour, he beats Hekmati up.

Nonetheless, a tentative relationship begins to grow between the teacher and the seamstress, while he devotes himself to singlehandedly restoring a rundown hall to make a community centre. He gains the respect of the boys in his class as well as the people of the neighbourhood, and yet the issue of an unacceptable romantic relationship gets him transferred to another area, with Ati not quite willing to risk social opprobrium by following him. Although Hekmati has gradually won a place in this community, he ends still an outsider, personal feelings defeated by deeply ingrained rules of conduct.

*

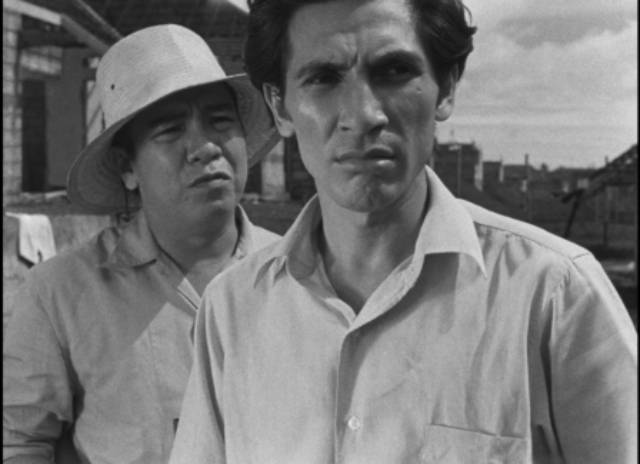

in Juan Bustillo Oro’s Dos Monjes (1934)

Dos Monjes (Juan Bustillo Oro, 1934)

While several of the films in the set are stylistically audacious, Juan Bustillo Oro’s Dos Monjes (Two Monks, 1934) in particular appealed to me. The earliest film in the set, made just as Mexican filmmakers were discovering sound and searching for themes and styles to reflect their nation during a time of social and political upheaval, it is a delirious romantic melodrama which draws on the visual extremes of German Expressionism while also plunging into avant garde narrative experimentation. Apparently, Bustillo Oro arrived at this feverishly distinctive style in part because he considered the script by Jose Manuel Cordero to be cliched and pedestrian. And it’s true that the romantic triangle at its core is quite trite; but cinema is not simply about story – it’s about how the story is told, and here Dos Monjes overflows with invention.

In a monastery, a monk named Javier (Carlos Villatoro) seems to have gone mad and the Prior (Beltran De Heredia) tasks the newly arrived Juan (Victor Urruchua) to try to drive out the devil. When Juan enters Javier’s cell, the latter reacts violently … and the film plunges into flashback to reveal that the two men know each other and have a fraught history. But it’s no simple explanatory flashback – we get the same narrative twice, once from each man’s point of view, shot in different styles to reflect their different memories and states of mind.

The framing scenes in the monastery have echoes of Dreyer in the large, sparse sets, the attention to faces and emotional states; while Javier’s flashback goes full-blown Expressionist with distorted sets, extreme camera angles, exaggerated contrast between light and shadow, Juan’s story has a more stable, naturalistic look. The two accounts contain the same primary elements, but each serves to exonerate the teller and blame the other.

Javier and Juan are the closest of friends, the latter more worldly because he has travelled. Javier falls in love with Ana (Magda Heller), a young woman who lives across the street with abusive guardians. When she’s kicked out, Javier and his mother take her in and romance blossoms. When Juan returns from his travels, things initially seem fine; he’s happy for his friend … but Javier eventually comes to suspect that Ana and Juan are betraying him. In a fraught confrontation, Ana ends up dead … though the details of what happened differ in the two accounts. By the time we return to the narrative frame, Javier’s madness overwhelms the film with an hallucinatory Gothic nightmare.

There’s an exhilarating air of creative freedom in Dos Monjes; while sound is used creatively (particularly with the transformation of a musical theme played early by Javier which becomes distorted as his madness grows), Bustillo Oro makes the most of the visual possibilities of late silent cinema. But as audacious as the film is, it proved something of a dead end for Mexican cinema, which went in a more conventional direction with a mix of naturalism, melodrama and comedy. And yet the film’s Gothic excesses eventually re-emerged a couple of decades later in the Gothic horrors of filmmakers like Fernando Mendez and Chano Urueta.

*

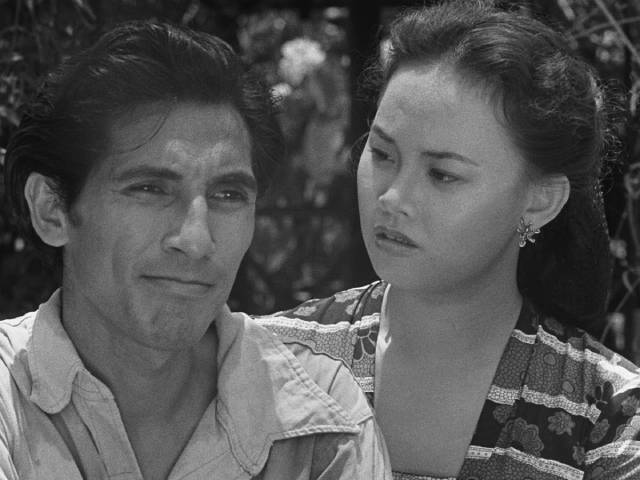

in Usmar Ismail’s After the Curfew (1954)

After the Curfew (Usmar Ismail, 1954)

Of the six films in the set, the final two in particular needed some external contextual information (provided by interviews on the disks and essays in the accompanying booklet) for me to fully understand what I was seeing. In the case of Usmar Ismail’s After the Curfew (1954), I had only the vaguest knowledge of Indonesian history, and that limited to the brutal consequences of Suharto’s dictatorship following the 1967 overthrow of Sukarno, the first president of independent Indonesia (and much of that comes from Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence).

Made just five short years after Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch in 1949, After the Curfew is steeped in disillusionment and anger. Iskandar (A.N. Alcaff) has returned from the war of independence traumatized by what he has seen and done. His hometown is under military rule as the new government establishes its authority and, as he walks to the house of his fiancee’s family, he is chased by an armed patrol because he’s violating the curfew. Here at the start he’s already out of sync with the country he fought for and his sense of disconnection only grows worse.

Civilians are not interested in what he did in the army; in fact they’re somewhat hostile, assuming that those who fought must feel superior to those who didn’t. His fiancee’s father manages to get him a job in a government office, but the other employees resent him for getting what they see as preferential treatment and he’s barely sat down at his desk before tension erupts in a fight and he loses the job.

He looks up some old comrades, one, Gafar (Awaludin), with a construction company involved in developing the town, another – his former commander Gunawan (R.D. Ismail) – now a high-powered businessman in competition with foreign firms. Gunawan offers Iskandar work as an enforcer, wanting him to go to a rival company and threaten the owner. This is not what Iskandar imagined he was fighting for.

When Iskandar runs into one of his old squadmates, Puja (Bambang Hermanto), now a petty crook and pimp, he learns the truth about the incident which haunts him from the war. He had been ordered by Gunawan to eliminate a family which was collaborating with the Dutch, an order he carried out despite being appalled that he had come to the point of killing women and children. But as bad as that was, he now hears that the family were actually just refugees and Gunawan had a side line in killing refugees and stealing their wealth, money with which he could finance his post-war business.

Knowing that Gunawan represents the new society, Iskandar realizes that the man who ordered him to commit murder will never face justice for his wartime crimes, so he sets out to avenge not only the victims but also himself, a decent man manipulated into horrific acts by the commander he felt allegiance to in what seemed a righteous cause. This course of action condemns himself as well as Gunawan – there’s no place for either of them if there’s to be any future for the country.

Ismail presents Iskandar’s moral struggle in personal and social terms which touch on multiple levels of the new society shaping itself after independence, showing more sympathy for those used and discarded like Iskandar himself and Puja, and the prostitute Laila (Dhalia), than for the middle and upper classes who have benefited most from others’ sacrifices. This is seen most clearly in Iskandar’s estrangement from his fiancee Norma (Netty Herawaty) and her family, who seem untouched by the war and oblivious of Iskandar’s inner turmoil.

*

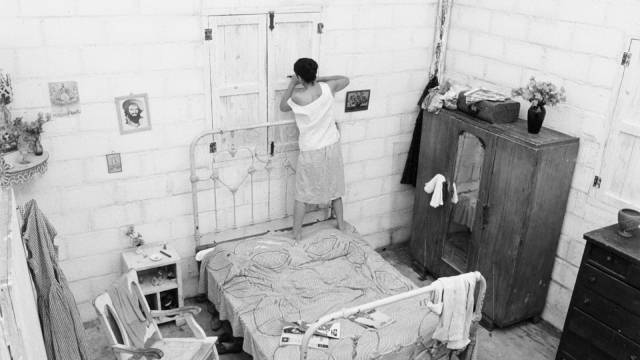

Lucia (Humberto Solas, 1968)

It seems remarkable that Cuban filmmaker Humberto Solas was only twenty-six when he made Lucia (1968), a complex three-part epic spanning seven decades of Cuban history as seen through the eyes of three women, all named Lucia. In its structure and its audacious style, the film inevitably recalls Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba (1964), but it avoids the propagandistic bombast of that masterpiece, embedding its history and politics in the lives of fully realized characters caught up in the inexorable flow of history.

The three parts are set in three pivotal periods (which, again, I needed some outside explanation for) pointing towards the Revolution which finally succeeded in 1959. In 1895, Cuba was fighting a war of independence against Spain. Many men have left to join the fighting, and a group of middle class women spend their time sewing clothes for the soldiers, sitting together and gossiping. Their surroundings and dresses are opulent and privileged even as wagons of dead and wounded fighters pass through the streets below.

Down in the street, a mad woman watches these horrors and rants; above, one of the women recounts the madwoman’s story – once a nun, she and her companions would walk over fields after a battle and bless the dead and dying. But one day, roving thugs chased these sisters of mercy and gang-raped them beneath hanging corpses. This sequence is an Expressionist nightmare, the horror puncturing the sense of security felt by Lucia (Raquel Revuelta), one of the listeners. That horror will gradually permeate her life, eventually bringing her together with the madwoman at a crucial moment.

Lucia is already getting beyond marriageable age, so when a handsome man begins to pursue her, she is drawn to him and a romance develops even though it risks offending propriety. Rafael (Eduardo Moure) is a businessman, half Cuban, half Spanish, who insinuates his way into her sheltered life; but when Lucia hears that he has a wife and children back in Spain, the betrayal complicates rather than negates her romantic feelings. To escape the humiliation, she takes him into the country where they can be together on her family’s plantation … a remote place where her brother and his comrades are based in their fight against Spain. A second and greater betrayal leads to Lucia’s own form of madness and her personal experience combines with the larger conflict to produce a desperate act of violence.

This first story is shot with a restless, expressive, frequently hand-held camera, the image becoming more extreme, with whites burning out much of the detail as Lucia’s life descends into chaos. The second story, set in 1932 during an abortive revolution against dictator Gerardo Machado, has a more conventional style as it tells of Lucia (Eslinda Nunez), the daughter of a middle class family now working in a cigar factory. She becomes involved with Aldo (Ramon Brito), a young revolutionary. Sent away by her father, she and her mother stay in a family retreat on the keys as tensions and violence increase in the city. But eventually, she joins Aldo and his friends, taking part in mass demonstrations as he takes up arms.

There’s a communal quality to their life together, eschewing convention while imagining a new kind of society where class doesn’t constrain individual freedom. But set-backs and increasing violence put strains on their relationship and Aldo’s death signals that the abortive revolution has reached a dead end. Almost three decades would pass before another dictator, Fulgencio Batista, would be overthrown and Cuba would achieve a degree of self-determination.

In the third story, taking place as the post-Revolution society pieces itself together, Lucia (Adela Legra) is a farmworker living among women like herself with a sense of shared purpose and enthusiasm for the rebuilding they are a part of. Then she meets Tomas (Adolfo Llaurado), a charming truck driver. After a brief courtship, they marry and her life abruptly changes in ways which quickly become intolerable. Issues of class and economics have been irrevocably changed by the Revolution, but patriarchal attitudes and machismo remain deeply embedded. As far as Tomas is concerned, Lucia is his possession. He forbids her to continue working; he forbids her to visit her parents; and he eventually forbids her to leave their house while he’s away at work.

Frustrated and stifled, Lucia is grateful when the government’s new literacy program reaches the community and a young tutor is assigned to teach her how to read and write. But this creates increasing tension between her and Tomas, who is infuriated by the idea of this man entering their house – a house he has taken to boarding up and locking when he leaves in his truck, Lucia condemned to wait for his return with nothing to do but clean and cook. The tutor urges her to rebel, and eventually she does, returning to work, only to have Tomas chase her and try to drag her back.

This section is made with a naturalistic style, playful in the early stages of Lucia and Tomas’ relationship, growing more tense and claustrophobic as it progresses. I was surprised to learn that this third story is widely considered to be a comedy, both by critics and Solas himself. Lucia’s struggle against male dominance seems too vital and intense, the final component of tradition to be confronted by the Revolution, to be viewed with amusement. She tells him he’s violating the Revolution, he says “I am the Revolution” and the potential for violence is palpable. Only in the final moments, as she concedes that she still loves him though she won’t tolerate his possessiveness, is there a sign that equality may yet be achieved.

That progress toward liberation and equality is embedded in the film’s structure and the progression of distinct cinematic styles, but also in the individual characters of the three Lucias. In 1895, constrained by social norms and destroyed when she tries to break free, Lucia is the tragic heroine of a melodrama; in 1932, she is a woman for whom a comfortable middle class life is no longer possible and she allies herself with a revolutionary who nonetheless still defines the terms of their relationship; but in the post-Revolution 1960s, Lucia refuses to be subordinate to anyone, determined to face life on her own terms.

Solas achieves a remarkable synthesis of cinematic styles which embody the very essence of the-personal-is-political. Dramatically complex and powerful, Lucia captures the sweep of history in vital terms through a close and detailed depiction of the lives of these three women.

*

The disks

As with the previous World Cinema Project sets, Criterion has released volume three in a nine-disk dual-format edition on three Blu-rays and six DVDs. While the films themselves are all impressive in their individual ways, the stories of their resurrection and restoration are nothing less than heroic. Most had to be pieced together from multiple sources which were frequently severely damaged – mould, vinegar syndrome, physical tears and missing pieces – and yet the visual quality is generally impressive, reflecting the enormous amount of time and effort which has gone into saving the films.

The supplements

Each film gets a brief (roughly three-minute) introduction from Martin Scorsese in his dual role as cinema enthusiast and World Cinema Project founder and patron, in which he briefly details why each film was chosen for restoration.

Each film is accompanied by a featurette which discusses the origins and context of the production. Humberto & “Lucia” (33:38) is edited from a documentary about Solas by Carlos Barba Salva; critic J.B. Kristanto (19:16) talks about After the Curfew; Charles Ramirez Berg (19:10) addresses Dos Monjes; Hector Babenco (21:47) speaks about the process of making Pixote; Med Hondo (21:30) shared his thoughts on Soleil Ô shortly before his death in 2019; and director Bahram Beyzaie (29:48) discusses the context of Iranian cinema against which Downpour was a reaction.

There’s also a brief prologue shot for the U.S. release of Pixote in which Babenco explains the context of the film for an audience unfamiliar with social conditions in Brazil.

A 76-page booklet contains invaluable essays on the World Cinema Project and each of the films, plus detailed notes on the restorations.

To date, the World Cinema Project has restored forty-one films from around the world. Criterion has released eighteen of them in three sets plus more than half-a-dozen in stand-alone editions – so we can look forward to additional releases which will continue to expand our knowledge of other national film cultures.

Comments