Ishiro Honda: Masters of Cinema

Masters of Cinema has recently issued two separate releases devoted to Ishiro Honda. As a master of kaiju eiga, he had followed the original Gojira (1954) with three more monster movies and four other sci-fi/horror films by 1961, when he made Mothra and altered the genre he had launched seven years earlier. Some of the themes are the same – the effects of atomic weapons, in particular, though here it’s the series of test explosions conducted by the U.S. on the Bikini Atoll rather than the bombs dropped on Japan that cause trouble.

After a storm wrecks a ship on Infant Island, several survivors are recovered. Although the island has been the site of multiple bomb tests by Rosilica (the silly name mocks the convention of not directly criticizing the U.S.), the sailors seem to be free of radiation poisoning. The reason for this appears to be an antidote given them by the island’s inhabitants. This is surprising news because there aren’t supposed to be any inhabitants.

A joint Japanese-Rosilican scientific expedition sails to Infant Island under the sponsorship of opportunistic businessman Clark Nelson (Jerry Ito). What they find is an environment damaged by radiation, with deadly mutant plants and a native tribe who have found a plant which counteracts the debilitating effects of the bombs. More surprisingly, the explorers discover a pair of twelve-inch tall fairies (played by twin singers Emi and Yumi Ito), who speak in unison and sing a haunting song. The fairies and the islanders just want to be left alone and spared any more bomb tests, something the scientists find entirely reasonable.

Nelson, on the other hand, smells potential profit and he returns with an armed team who kill some natives and kidnap the twins, taking them back to Japan to display in a cabaret act. Other members of the expedition object and argue that the twins should be released. Much of the movie is concerned with this conflict – decency vs capitalist arrogance and greed, Japan vs America … er, Rosilica. Only in the final stretch does it become a monster movie – but here the monster is utterly unlike the rampaging saurians of kaiju tradition.

The twin fairies sing their plaintive song and awaken the god-like creature guarded by the natives of Infant Island: Mothra. A giant egg hatches into a giant larva which sets out to swim to Japan, sinking a ship along the way and wreaking havoc as it gets to Tokyo. Pressure is put on Nelson to release the twins, but he denies the destruction has anything to do with him and quickly takes them to Rosilica where a court rules that the fairies are his property and he can keep them.

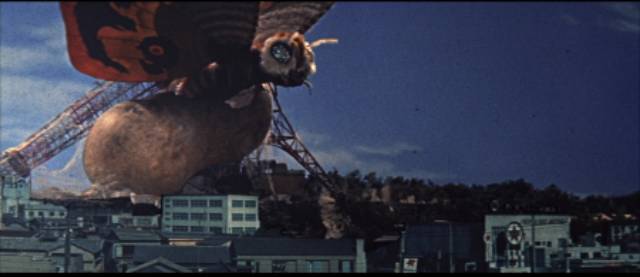

The larva spins a cocoon in the ruins of Tokyo and soon hatches out as Mothra, the most visually arresting of all kaiju – and, I think, if not the only one specified as female, then certainly one of very few. She flies to Rosilica and wreaks more havoc, her wings generating powerfully destructive winds. With the devastating consequences of Rosilica’s bomb tests and rampant capitalism finally brought home, the authorities turn against Nelson and he ends up dead in a gunfight. The twins are delivered to Mothra, who takes wing and flies back to Infant Island.

Mothra combines its satire of capitalism and American imperialism with an unexpected sweetness, the twins and the giant moth transforming the kaiju narrative into a uniquely cinematic fairy tale. Unlike the more blatant shift supposedly catering to a core audience of children which produced the likes of Jun Fukuda’s Son of Godzilla (1967), Mothra is a fairy tale for adults, infusing the military and political metaphors which gave the genre its original impetus with a sense of poetry.

The Masters of Cinema edition comes in a sturdy case with a 60-page book of essays and interviews. It includes both the original Japanese (101-minute) and U.S. (90-minute) cuts, with a new David Kalat commentary on the former and an archival commentary by Honda biographers Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski on the latter. There’s also an interview with Kim Newman. The one disappointment is that everything is crammed onto a single disk, with the U.S. cut getting a less robust encoding than the (always preferable) Japanese version.

*

The other MoC release is a Honda double-feature, two non-kaiju sci-fi movies which again are presented in their original and U.S. versions. This set has its own disappointment, for me at least, as it includes one of Honda’s dullest movies, Battle in Outer Space (1960), rather than something more worthwhile like The Mysterians (1957) or Matango (1963).

Battle was an attempt by Toho to move in a new direction – away from giant monsters and, perhaps more significantly, off Earth. Much of it takes place in space and on the moon, affording new challenges to effects master Eiji Tsuburaya. While the effects team do impressive work, the story and characters remain stubbornly dull. Humanoid aliens are intent on conquering Earth and have established a base on the moon. They have the ability to take control of selected humans, remotely controlling them to sabotage the efforts of united Earth forces to mount a counterattack.

Two ships are launched, fighting their way to the moon past enemy ships and meteors and, once there, encountering a handful of not very menacing aliens before destroying the enemy base. Battle in Outer Space is something like a throwback to early ’50s movies like Destination Moon (1950) and Conquest of Space (1955), more elaborate certainly and with the added menace of hostile aliens, but still mostly an excuse to mount special effects sequences, with characters little more than place-holders. (The film also seems to have influenced the Gerry and Sylvia Anderson puppet series Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons [1967-8].)

The real attraction of the set is The H-Man (1958), an imaginative genre-hybrid which begins as a noirish crime movie and complicates things by introducing a radiation-induced horror element. There are back alleys, nightclubs, torch singers and cops on the trail of drug dealers … plus mutant slime oozing through the city’s sewers, growing by absorbing more and more people into its glowing goo. (The slight resemblance to The Blob is purely coincidental as Honda’s movie was released in Japan months before the American film premiered in the States.)

Hearkening back to Gojira and its origins in the fate of the fishing boat Lucky Dragon 7, whose crew had been caught down wind of an American hydrogen bomb test which contaminated them with fallout, the H-Man has its origin in a similar event. This we eventually see in a flashback which explains the mysterious events being investigated by police, who begin by tracking drug dealers and find themselves with suspects who disappear, leaving their crumpled clothes behind. Before long they see the slime at work, flowing through windows and under doors and creeping up people’s pants legs to dissolve them.

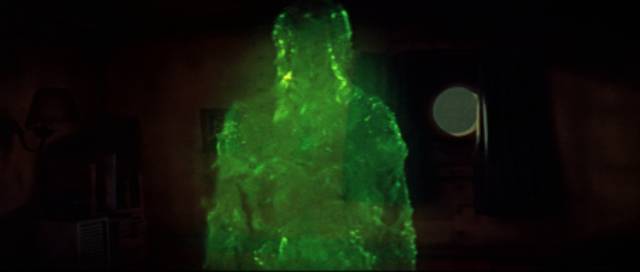

In the flashback, a ship’s crew discover what appears to be a deserted vessel. Seeing a salvage opportunity, they board and discover empty clothes and a captain’s log cut off in mid-sentence. But the ship hasn’t been abandoned; the crew have been transformed, the glowing slime drawing itself up into vaguely human shapes suffused with a ghostly green glow. A couple of men are lost to the goo, others escaping back to their own ship. Looking back, they see the ghostly crew gathered on the derelict’s deck. It’s a haunting image, a reminder that the monster was once human and subjected unwillingly to a horrific transformation.

Back in Tokyo, a scientist has figured out what’s going on and he eventually manages to persuade the police. The only way to defeat the unwitting monster is by electrocution or fire and a campaign is launched to pour gasoline into the city sewers and ignite them…

Honda does a nice job balancing the cops-and-criminals and monster elements, getting a chance to show his skills with more conventional dramatic material while also dealing with an original menace which takes on supernatural overtones, conflating the atomic element with ghosts who may still possess some aspect of their human identity.

As in the Mothra release, both movies get commentaries from Kalat, Ryfle and Godziszewski, once again dividing duties between the Japanese and U.S. versions. There’s also a booklet with essays about each film.

Comments