Recent Arrow viewing

I’m still virtually buried under the stacks of Blu-rays I was compulsively ordering over the summer during lockdown … the habit got worse as it wasn’t possible to get out to the few local stores that still sell disks. Browsing actual shelves acts as a kind of natural limiter; I tend to be more selective when I’m holding the disks in my hand. The weightlessness of on-line ordering encourages an unreasonable profligacy and looking at the backlog, I’m sometimes baffled about why I bought a particular title. Do I actually want to watch it? What was the impulse to own it all about?

Various on-line sales have produced a substantial backlog of Arrow releases, made worse by a bunch more which were already sitting on my to-watch shelf.[1] Compared to what’s waiting there, the ones I have recently watched hardly amount to a hill of beans … and I’m well aware that my taste and integrity as a lover of fine cinema are seriously undermined by the viewing choices on display here – more trash than art! (I’ll tackle one of my other favourite labels, Indicator, in an upcoming post.)

Killer Nun (Giullio Berruti, 1978)

It’s not surprising that as a genre nunsploitation was largely an Italian phenomenon, given the dominant political and social position of the Catholic Church in that country, with France close behind. The fierce sexualization of “the brides of Christ” speaks of a deep-seated resentment of the Church’s power over civil society. It’s not surprising that the greatest film which touches on the genre, though the work of an English filmmaker, was set in France and made by a Catholic; Ken Russell’s The Devils indicates that exploitation tropes can be put to serious artistic and political purposes.

Giullio Berruti’s Killer Nun (1978) doesn’t rise to that level, but it undeniably has more serious things on its mind than mere titillation. Based on an actual case in Belgium, in which a nun working in a hospital killed a number of patients, Berruti’s movie sets out to explain how someone supposedly committed to selflessly helping the sick could end up a murderer. His vehicle is Sister Gertrude, a strict, authoritarian figure in the hospital who, following a painful operation, became addicted to morphine. Struggling with her addiction, the sister is gradually losing control, unable to suppress her sexual urges as her calling dictates – she slips away into the city, dressing provocatively and picking men up in bars, while back at the convent her resistance to the overtures of Sister Mathieu (Paola Morra) is crumbling. All this stress produces spontaneous outbursts of anger and eventually blackouts during which she does things like cutting off a patient’s oxygen.

Drugs, murder, illicit sex, encroaching madness … nothing surprising here, and all handled with commitment by Berruti. But what is strangely disorienting in Killer Nun is the presence of Anita Ekberg as Sister Gertrude; the image of her voluptuous international movie star Sylvia in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) hangs over the movie. Sylvia’s sexuality flaunts convention, representing the throwing off of outmoded moral constraints; but for Sister Gertrude her role as a nun prohibits such public display and turned inward her sexuality becomes destructive rather than liberating. The bluntness of the film’s title conceals what turns out to be an interesting examination of a character in psychological distress. (Commentary by Italian genre experts Adrian J. Smith and David Flint, video essay on nunsploitation by Kat Ellinger, interviews with Berruti, editor Mario Fiasco and actress Ileana Fraja)

*

Flowers in the Attic (Jeffrey Bloom, 1987)

Unhealthy sexual repression and forbidden behaviour was the source of popular appeal for a series of books by V.C. Andrews, written between 1979 and 1984, about a wealthy family plagued by religious mania and incest. Considering that the books were all about a group of siblings being horribly tortured by their grandmother and complicit mother, the older boy and girl finding solace in an incestuous relationship, it seems odd that Andrews’ readers were mostly adolescent girls. And considering the inherent problems with the thematic content, it’s not surprising that, despite their popularity, Hollywood had a hard time figuring out how to cash in with a movie adaptation.

Eventually the project landed in the lap of writer-director Jeffrey Bloom, a television and movie writer with occasional undistinguished directing credits. Having never read the books, I can’t gauge the quality of his adaptation – he apparently offended some fans with a major change to the ending, which made for a more satisfying conclusion to the movie but cut off the possibility of continuing with the sequels. I can’t speak to that, but I can say that Flowers in the Attic (1987) is more entertaining than I expected, a somewhat queasy modern Gothic which generates a stifling hothouse atmosphere.

Following the accidental death of their father, which leaves the family unexpectedly destitute, the Dollanganger kids are uprooted from their home and taken by their mother Corinne (Victoria Tennant) back to her parents’ sprawling estate. They get a frosty welcome because their mother was disowned years ago for marrying their father (we eventually learn that they were close blood relations, so incest is kind of a family tradition) and she has not been forgiven. Grandma Olivia (Louise Fletcher), a grim religious fanatic, sees the kids as abominations and insists that they be locked away in rooms upstairs while Mom tries to win back her parents’ affection so they can become rich and comfortable.

It takes a while for the kids to realize that Mom is coming to see them less and less frequently, making no attempt to protect them from Olivia’s harsh punishments for imagined infractions, and they begin to suffer from neglect. Eventually the youngest son gets sick and dies and the others attempt to break out of the family prison. What they discover is even worse than they thought; their mother has become engaged to lawyer Bart Winslow, who has no idea she was previously married and has children. The kids have been erased as the price for Corinne’s reintegration with the family. Worse still, Corinne is slowly poisoning them to ensure her inheritance and the success of her upcoming marriage to Bart.

Left to their own devices, the two older kids, Cathy (Kristy Swanson) and Chris (Jeb Stuart Adams), have become surrogate parents to the younger ones, their imprisonment actually fostering the “sin” Olivia rails against. This brew of religious mania, incest and infanticide constantly threatens to tip over into parody, but Bloom and his cast manage to keep it on the rails. It may not be as elegant and finely-wrought as Guillermo del Toro’s Crimson Peak, but it belongs to the same Gothic romance lineage. (Commentary by Kat Ellinger, interviews with cinematographer Frank Byers, production designer John Muto, composer Christopher Young, actor Jeb Stuart Adams, plus the original ending which was vetoed by the studio)

*

Hired to Kill (Nico Mastorakis, 1989)

Greek writer-producer-director Nico Mastorakis may not be a great filmmaker, but he dies seem to have a knack of some kind. I find his work a little dull, but nonetheless entertaining for the odd and unexpected choices he occasionally makes – the attractive young couple in Island of Death, for instance, who would usually fall victim to murderous locals yet turn out to be an incestuous brother and sister who have arrived on the island to indulge their psychopathic compulsions.

Hired to Kill (1989) is the third of his features I’ve now seen, thanks to Arrow, and while it falls short of Island of Death and The Wind, it plays with the post-Rambo mercenary formula in ways which indicate an awareness of the conventions and a sense of humour about their inherent absurdity. Here, a former soldier is reluctantly recruited by a CIA handler to infiltrate a Latin American dictatorship to rescue an imprisoned popular leader and aid rebels in the overthrow of the brutal strongman ruler.

The hero is non-nonsense Frank Ryan, played by rugged, big-jawed Brian Thompson. Handler Thomas (George Kennedy) provides Ryan with a cover as a gay fashion-designer, while his all-female team pose as supermodels, invited to present his new line in the repressive country to help burnish the sophisticated image of dictator Bartos (Oliver Reed). While Ryan is a misogynist asshole, he goes all-in on his role, at one point planting a long lingering kiss on Reed’s lips as he pretends to believe the dictator has been coming on to him.

Filling out the cast is Jose Ferrer as Rallis, the imprisoned revolutionary, a tired old man who may not be able to live up to his image as an inspirational leader … not that it matters, because naturally the whole mission is bogus. Thomas has deals with multinationals eager to rip off the country’s resources and the plan is actually to crush the revolution and kill Rallis. Ryan’s loyalties remain uncertain – does his eventual change of mind signal a moral choice or mere expediency? Whatever, by the climax he has bonded with his team and returns to Miami to take care of Thomas.

Hired to Kill plays much of the story straight, superficially resembling any one of a number of such mission movies, but it keeps throwing in those odd twists which signal that it’s mocking what the audience has come to see. You couldn’t call it enlightened in its treatment of women and gays, but it marshals the female mercenary team and Ryan’s gay cover role to punch holes in the hyper-masculine (and frequently homosexually-coded) elements of the genre. (Commentary by editor Barry Zetlin, interviews with director Mastorakis and star Thompson)

*

Children of the Corn (Fritz Kiersch, 1984)

I didn’t see Fritz Kiersch’s Children of the Corn when it came out in 1984. Although I was a faithful reader of Steven King’s work, and had been since reading Carrie in paperback in 1975, followed immediately by Salem’s Lot in hardcover. By 1984, there’d been seven or eight more novels, but King wasn’t yet a movie box office powerhouse; despite the ambiguous prestige of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), adaptations had remained modestly budgeted and personally I didn’t find most of them that interesting – the best seemed to me to be David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone (1983), and that was mostly because I was a Cronenberg fan.

When Children of the Corn came out, the reviews weren’t particularly good and I didn’t bother. Time passed and it spawned a bunch of sequels, prequels and remakes (there seem to be eleven in total now). That seems like an awful lot to be built on a single short story, a story which even at the time it was published seemed derivative of Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? which had been released a year before publication. So somehow thirty-six years passed without me ever seeing the movie.

I’m not sure what I think about it, having gone in with limited expectations which were definitely not exceeded. Although it’s well shot and the cast is generally competent, it just kind of sits there. Linda Hamilton is very appealing as heroine Vicky (just before she hit it big in The Terminator a few months later), but Peter Horton as her domineering husband Burt is irritating. There’s a lot of repetitive action – pursuits, captures, escapes and more pursuits – but each iteration doesn’t add much to what we already know. Although John Franklin was twenty-five at the time, his diminutive stature as cult leader Isaac gives him the air of a really creepy child. Many of the other children are vaguely disturbing in that oblivious, amoral way that kids have as they enact cruelty without any apparent self-awareness.

But apart from the bloody prologue, it all feels kind of aimless and under-developed, the psychological possibilities remaining dormant and eventually wiped away when the malevolent supernatural entity rears its pre-CG head out of the cornfield. The movie’s not terrible, but it feels routine and uninspired … it’s baffling that it somehow spawned a franchise that has lasted almost forty years. (Two commentaries, one with director Kiersch, the other with journalist Justin Beahm and historian John Sullivan, multiple cast and crew interviews, a retrospective documentary, plus a short film adapted from King’s story in 1983)

*

Edge of the Axe (Jose Ramon Larraz, 1988)

The work of Spanish filmmaker Jose Ramon Larraz – at least what I’ve seen of it – mixes art and exploitation in interesting ways, putting him in the company of people like Jean Rollin and Walerian Borowczyk. Late in his career, he made a couple of slashers (towards the end of that genre’s heyday), both set in the U.S., though partially shot in Spain, giving them a slightly off-kilter flavour similar to his earlier films set in England. The first of these, Edge of the Axe (1988), is the more successful, hitting the genre notes perfectly while managing to remain fresh. A small California town is beset by a series of brutal murders while outsider Gerald (Barton Faulks) tinkers with computers and gets involved with teenager Lillian (Christina Marie Lane) while doing some amateur detective work which leads him to a troubling conclusion about the masked killer’s identity.

Larraz makes good use of locations, stages effective murders and gives some depth to the characters who rise above the standard cardboard cutouts waiting to be dispatched by a plot-device killer. (Two commentaries, one with star Faulks, the other with The Hysteria Continues, several cast and crew interviews)

*

The Dead Center (Billy Senese, 2018)

American remakes of Japanese horror movies are almost always disappointing, never really capturing the special qualities of the originals. Writer-director Billy Senese, however, comes very close to those qualities with this original project, telling a story in an oblique, suggestive manner reminiscent of someone like Kiyoshi Kurosawa. The Dead Center (2018) is haunting and grows increasingly creepy as it unfolds. If it gets a bit too explicit towards the end, what comes before is so effective that it’s a minor quibble.

Dr. Daniel Forrester (Shane Carruth, director of the great time travel movie Primer) is a psychiatrist working in an emergency ward, overly committed to his job and stressed to breaking point. Concerned only with the pain of the people who come looking for help, he has no time for bureaucratic rules and budgetary issues; although reluctantly tolerated by administrator Sarah Grey (Poorna Jagannathan), an old friend, he is edging towards disciplinary action and possibly dismissal. And then an unnamed patient appears in one of the rooms on his ward, a catatonic whom no one admitted. That’s because he’s a suicide who was brought into the hospital morgue after bleeding to death in a motel bathtub. Having come back to life, this man has slipped unnoticed out of the morgue, found his way to a room with an empty bed, and curled up beneath the covers.

The narrative follows two distinct threads – medical examiner Edward Graham (Bill Feehely), having found the body he was to examine missing, sets out to identify the motel suicide, a quest which eventually leads him to another town and a family whose son was the only survivor when his house burned down, leaving his wife and kids dead. This man, Michael Clark (Jeremy Childs), was changed by the experience in disturbing ways, undergoing a severe alteration in his character to the point where his parents became afraid of him.

The John Doe that Dr. Forrester is trying to figure out is this Michael Clark. When he emerges from his catatonic state, he swings wildly between fear and violent anger. He claims that he died in the fire but came back, and brought something back with him. That something is a demonic force which feeds on pain and drains the life force from people, growing stronger the more it feeds. Forrester, in trying to figure out what he believes is Clark’s delusional pathology, gradually loses his grip on his own sanity, breaks a few rules too many, and is ordered off the case when it appears that he has himself become unhinged and violent. Of course, no one believes his story of possession and Clark is discharged, leading to a climactic suburban bloodbath as the demon returns home and embarks on a spree which can no longer be contained.

Senese maintains an understated tone, allowing the narrative to emerge from scenes which mostly retain a matter-of-fact realism. Carruth and Childs give excellent performances, with the rest of the cast providing strong support. Relying more on creeping unease than overt shocks (though there are some of those), The Dead Center gets under your skin in that satisfying way familiar from Japanese horror movies. (Two interviews with director Senese, joined in one by Carruth and Childs and in the other by producers Denis Deck and Jonathan Rogers plus cinematographer Andy Duensing, making-of, cast interviews, deleted scenes, two short films and seven radio plays by Senese)

*

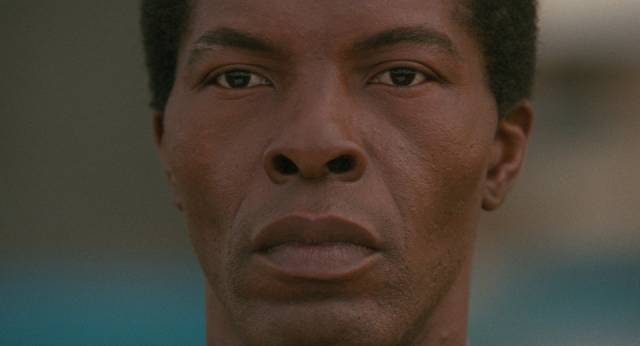

The Limits of Control (Jim Jarmusch, 2009)

I didn’t see Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control (2009) when it came out and I’m not sure why. Being swayed by unenthusiastic reviews is hardly an excuse; I’d previously liked Jarmusch’s work regardless of what the critics thought, and had really liked his previous feature, Broken Flowers (2005). Whatever the reason, I’ve only just seen it for the first time in the wake of revisiting Ghost Dog (1999). And I’m a little ambivalent.

Following an enigmatic, unnamed man (Isaach De Bankolé) through a series of cryptic encounters as he travels across Spain on an unexplained mission, perhaps more than any other Jarmusch movie The Limits of Control refuses to give the audience a clear narrative to hang on to. The unnamed man barely speaks, listening impassively as each person he encounters embarks on a discursive monologue about seemingly random subjects. At each of these encounters (Tilda Swinton, John Hurt, Gael Garcia Bernal, Paz de la Huerta, and others), the man is given a brief coded message which leads to the next location, the next contact, until he finally arrives at his destination – a heavily guarded compound where lives an obnoxious American who lectures the man on geopolitical “realities” which amount to U.S. interests at the expense of everyone else on the planet. Turns out our enigmatic protagonist is an embodiment of all those others, come to exact revenge on that American arrogance.

Jarmusch has long favoured an episodic structure, but here there is little sense of forward momentum. The film feels enervated, and de Bankolé’s determined lack of expression never allows us to get inside events. The various monologues are interesting, but I found myself growing impatient waiting for something to illuminate what was going on … by the time we reach the compound and the American spells out his utterly bankrupt view of the world and our relative place in it, it seemed too late and too pat. I’ll eventually get around to watching it again, and knowing now not to expect the delivery of the thriller it initially appears to be, perhaps I’ll be able to enjoy for their intrinsic qualities all those individual moments with the excellent cast. (Interview with critic Geoff Andrew, video essay by critic Amy Simmons, archival making-of)

*

Three Brothers (Francesco Rosi, 1981)

Francesco Rosi followed his ruminative epic Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979) with another quiet, contemplative film which strives to sum up the social, political and economic state of the Italian nation at the end of the 1970s. Like Eboli, Three Brothers skirts a sentimental nostalgia for the pre-industrial peasant society of Southern Italy; also like Eboli, it manages to sidestep that risk by being attentive to concrete details of place and the psychological nuances of characters who possess an almost archetypal quality.

When patriarch Donato’s wife dies, he stoically walks to town to send brief telegrams to his three sons, all of whom left their rural home years ago for lives in different cities – Raffaele, a judge, to Rome; Rocco, in charge of a reformatory, to Naples; and Nicola, a union activist, to Turin. Their roles present a schema of socioeconomic conditions, each reflecting current failures and possibilities for reforming Italian society. Raffaele lives under the threat of political violence as he contemplates taking on a case against terrorists; Rocco strives to save dispossessed kids from an almost guaranteed life of crime and imprisonment; while Nicola fights against capitalist bosses exploiting workers.

As they gather at the family home, they reconnect with the past – a wartime childhood, potential relationships abandoned – while trying to reconcile with one another and a father who still lives in that past. Together, they represent a generation which has fragmented and is now floundering as it tries to find some sense of direction. The past is lost and the future uncertain. And yet Rosi hints at a bridge in the warm relationship between Donato and Nicola’s young daughter Marta, a child as yet seemingly untouched by the social chaos which has shaped the brothers’ lives and able effortlessly to connect with the old man, suggesting the transience of political turmoil and an enduring quality in life lived rooted to the land.

Although filled with discussions and arguments about the brothers’ conflicting views, the film feels (again, like Eboli) filled with the breath of life, the sheer vibrancy of existence. Rosi and cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis are as sensitive to sun-scorched landscapes as they are to expressive faces, giving the setting a powerful physical presence and populating it with flesh-and-blood characters who seem to grow naturally from this environment. The cast breathes life into what might have been mere mouthpieces for particular points of view – Philippe Noiret as Raffaele, Michele Placido as Nicola, Vittorio Mezzogiorno as Rocco, Charles Vanel as Donato and Marta Zoffoli as Marta – and the film is rich in the complex emotions which bind a family and also threaten to tear it apart. (Audio interview with Rosi from the National Film Theatre)

*

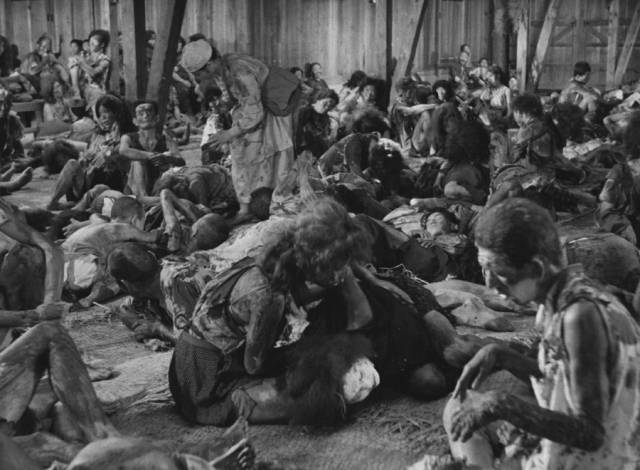

Hiroshima (Hideo Sekigawa, 1953)

I haven’t seen Kaneto Shindo’s Children of Hiroshima (1952), a film adapted from a book of first-hand accounts of the August 6, 1945, atom-bombing of the city. It was sponsored by the Japan Teachers’ Union, which deemed it too arty and sentimental. So they tried again the following year, this time with leftist filmmaker Hideo Sekigawa, whose approach was bluntly political, which made for a powerful film but caused distribution problems.

Beginning in the present, a high school class listens to a radio report on the bombing. It gives a moment-by-moment account from the American perspective, triggering a traumatic response from a number of students who are survivors suffering from leukemia. From here, the majority of the film is a long, graphic flashback to the day of the bombing and its aftermath. The focus is on children, their parents and teachers, and the atmosphere is one of horror, confusion and terrible pain as the kids get lost in the ruins, witness the physical devastation inflicted on family and friends, and see the adults who they depend on for security rendered helpless and mad.

The attack and aftermath are depicted on a huge scale, drawing on support from the city of Hiroshima and many survivors (reportedly, as many as 90,000 people were involved in the reconstruction of the event). Not only is the account graphic – mad and badly injured people wander like phantoms through the burning ruins – Sekigawa also weaves through the chaos a critique of the social and political forces which brought the city to this point; the teachers who had taught their charges to devote their lives to the Emperor and Imperial Japan, the military which is so committed to death in service of the Empire that they are virtually useless in the aftermath.

But the film doesn’t stop with the event itself. It covers the ensuing eight years, following the victims as they deal with the lasting trauma, both physical and psychological. If the wartime authorities were largely responsible for the destruction, the postwar authorities were also problematic – survivors, sick and scarred, were shunned as an embarrassing reminder of events best forgotten; orphaned children did what they could to survive on the streets, committing petty crimes and, in one of the film’s most disturbing revelations, peddling bombing souvenirs to American tourists … like the unearthed skulls of victims.

These things, along with a pointed critique of the U.S. and the ensuing occupation, ran into the censorship of the period and caused all the major film companies to refuse any help in distribution. Although the Teachers’ Union ended up self-distributing the film, screening it in schools around the country, it quite quickly slipped into obscurity before being revived in the past decade.

Sekigawa avoids any overt artiness which might aesthetically distance the audience from what is being shown. His approach is instead one of almost detached documentary observation which permits direct access to the horror of the bombing and its aftermath, suggesting a direct influence on Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1966) and Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984). The difference, of course, is that the latter two films pose possible future horrors, while Hiroshima is a sober account of actual events. (Video essay by Jasper Sharp, archival interview with actress Yumeji Tsukioka, 2011 feature-length documentary on survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings now living in the U.S.)

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) I just sorted them all out and feel pretty overwhelmed. Admittedly, quite a few of these releases were upgrades from DVD or earlier Blu-ray editions, so they don’t prompt any real sense of urgency – kind of collection maintenance, in a way. But what’s my excuse for allowing others to linger on, waiting for me to get around to them? Here, in no particular order, are the titles which now constitute my “Arrow burden”…

Box sets:

Shinya Tsukamoto’s Solid Metal Nightmares (I’ve only watched Tetsuo and its sequel so far)

The Complete Sartana (I watched the first two movies, but never got around to the other three)

Waterworld (I watched the extended version, but not the other two cuts, nor most of the extras)

Phenomena (I watched the long Italian cut, but not the shorter international nor the really short US versions)

Kenji Fukasaku’s New Battles Without Honour and Humanity

Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive Trilogy

Miike’s Black Society Trilogy

Outlaw Gangster VIP: The Complete Collection

Three Films by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

De Niro and De Palma: The Early Films

Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years vol. 1

Seijun Suzuki’s The Taisho Trilogy

Akio Jissoji’s The Buddhist Trilogy

Godard + Gorin: Five Films 1968-71

The Jacques Rivette Collection

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalog

Kiju Yoshida’s Love + Anarchism

Fukasaku & Miike’s Graveyard of Honor

Single disks – upgrades:

Robert Altman’s Gosford Park

Alfred Sole’s Alice, Sweet Alice (aka Communion)

Philip Ridley’s The Passion of Darkly Noon

Terry Gilliam’s Tideland

Roger Donaldson’s Sleeping Dogs & Smash Palace

Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep

Ulli Lommel’s Tenderness of the Wolves

Jack Hill’s Spider Baby

Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand

Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth

Jacques Tourneur’s The Comedy of Terrors

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso

Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion

Mario Bava’s Erik the Conqueror

Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia

Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity

Alain Resnais’ Melo

Larry Cohen’s The Stuff

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist

Single disks – previously not part of the collection, and mostly not previously seen by me:

Francois Reichenbach’s America as Seen by a Frenchman

Tomu Uchida’s The Mad Fox

Kirill Sokolov’s Why Don’t You Just Die!

Mohamed Diab’s Clash

Kleber Mendonca Filho’s Aquarius

Aleksei German’s Khrustalyov, My Car!

Frank Henenlotter’s Brain Damage

Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe

Roberto Rossellini’s Viva L’Italia

William Friedkin’s Cruising

Andrzej Zukawski’s Cosmos

Vincent Ward’s Vigil & The Navigator

(return)

Comments