Recent Eureka/Masters of Cinema releases

Among Eureka’s recent releases have been a lot of Asian movies. Already received but not yet viewed: Fruit Chan’s Made in Hong Kong (1997), Three Films with Sammo Hung (Hung/Yuen Woo-ping, 1977/79/87), Wheels on Meals (Hung, 1984). On the way: Ronnie Yu’s The Bride With White Hair (1993), Ricky Lau’s Mr. Vampire (1985), and Ishiro Honda’s Mothra (1961), The H-Man (1958) and Battle in Outer Space (1959). And pre-ordered: Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China Trilogy (1991-92). What I have watched recently from this Asian plethora is a two-disk set of early films by John Woo.

John Woo

Although John Woo became an international phenomenon with the stylish gangster movies he made between A Better Tomorrow (1986) and Hard-Boiled (1992), which led to his uneven Hollywood career, he learned his craft with a series of ’70s martial arts films for the Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest. The Eureka set includes The Hand of Death (1976) and Last Hurrah of Chivalry (1979). Both films adhere to genre conventions while also transcending the limitations of genre. Not only does Woo fill the movies with often spectacular and audaciously extended action scenes, already making judicious and effective use of slow motion, he also creates characters with some depth, investing the narratives with dramatic stakes.

He also lays out the thematic groundwork which would become familiar from the later gangster films – betrayals and atonement, friendships forged between rivals who must finally confront one another, heroes who adhere to a code of honour which the villains have violated. There are touches of humour which derive from character and visceral displays of violence. And casts full of recognizable faces who would soon become stars, including a young Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao. Strangely, despite delivering on all the popular genre elements, neither film was a big box office success in Hong Kong … perhaps confirming that audiences weren’t interested in adding depth to the formula (King Hu’s masterpieces also weren’t embraced by a popular audience). But both of Woo’s movies can now be seen as superior examples of period martial arts filmmaking in which character is as important as action. Both films look vivid and colourful on Blu-ray, and each has multiple audio options plus a commentary track from genre expert Mike Leeder and filmmaker Arne Venema, along with brief archival interviews with writer-director Woo.

*

Bela Lugosi

Bela Lugosi’s exoticism, with his hypnotic look and heavy accent, made him a kind of star but generally kept him from straight roles in mainstream movies. He worked a lot in the 1930s in the wake of Dracula (1931), but much of that work was in low-budget B-movies, often produced by poverty row studios. The occasional part for a bigger studio would usually be in a supporting role, like his Sayer of the Law in Paramount’s perverse Island of Lost Souls (Erle C. Kenton, 1932) and a Russian General in the ensemble comedy International House (A. Edward Sutherland, 1933). His frequent relegation to mad scientist roles in minor horror movies tormented him throughout his career, leading eventually to his sad drugged-out final years starring in movies for Edward D. Wood Jr.

But for his fans, it’s those horror roles that are most warmly remembered rather than something like his Russian Commissar in Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939). Among the dross, there are quite a few gems like Victor Halperin’s White Zombie and William Cameron Menzies’ Chandu the Magician (both 1932). Eureka has gathered three of these early movies into a two-disk Blu-ray set for their Masters of Cinema label. All produced by Universal in the wake of their success with Dracula and Frankenstein (1931), like those hits they sought respectability by claiming literary origins while indulging in sordid pre-code antics. “Adapted from Edgar Allan Poe”, all three invented new narratives which incorporated a few elements from Poe stories and poems, while plunging into Gothic melodrama steeped in intimations of sex and violence.

Murders in the Rue Morgue (Robert Florey, 1932)

Robert Florey’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) had been handed to the director as a consolation prize when the studio took Frankenstein away from him and gave it to James Whale. All that remained of Poe’s story was a murder committed by an ape, while everything else was invented by Florey and several co-writers (including John Huston). Detective C. Auguste Dupin becomes medical student Pierre Dupin (Leon Ames), while the murderous orangutan becomes Erik, a gorilla belonging to mad scientist Dr. Mirakle (Lugosi) who funds his research by displaying Erik in a sideshow. In 1845 Paris, he wants to prove his radical theory of evolution by mixing the blood of the gorilla with that of a human woman. Repeated failures lead to a string of murdered women turning up in the Seine.

Pierre’s penchant for hanging out at the morgue gets him interested in investigating the deaths. Visiting the carnival one evening with friends and his fiancee Camille (Sidney Fox), he sees Mirakle’s performance and almost gets choked by the ape. Erik, meanwhile, becomes very interested in Camille. Needless to say, Mirakle kidnaps Camille, who being a respectable woman has the pure blood he needs for his experiments (all his previous victims were prostitutes and thus tainted). Things rush towards a climactic rooftop chase and last-minute rescue.

Lugosi is pleasingly sinister as the mad doctor, while Ames is a bland hero. Erik is mostly Charles Gemora in his famous gorilla suit, unfortunately too frequently intercut with close-ups of a mismatched chimpanzee. As with so many mad scientists the point of Mirakle’s experiments remains unclear, but the studio-built Paris streets have a lot of atmosphere which Karl Freund’s cinematography makes the most of.

What’s really interesting about the disk is the attention it draws to front-office interference in even a lower-budget production like this. Murders in the Rue Morgue has never had a great reputation, in large part because of its disjointed narrative – something which has long diminished Florey’s reputation. Included in the booklet is a reprint of an article by Tim Lucas from an issue of Video Watchdog in which he proposes a reorganization of the film, pointing out from internal evidence (action and dialogue) a more plausible narrative progression (his suggestions are elaborated on by correspondent Gary L. Prange in a letter from a later issue of VW). All very intriguing … but it was some time after watching the movie that I learned from DVD Beaver that this re-edited version is included as an Easter egg on the disk.

Lucas and Prange’s proposed “director’s cut” turns out to be a far superior film, its narrative tightly constructed and moving quickly with a logic that steadily builds tension. Almost all of the changes occur in the first half and, since they work so well, we’re left wondering why the studio mandated the changes in the first place. The most obvious reason is that someone decided it was necessary to introduce Pierre and Camille off the top and get Erik in as soon as possible – so the film starts with the visit to the carnival instead of leading off with Mirakle abducting and killing several prostitutes, tormented by his failure to obtain the results he wants before finally setting eyes on Camille. This alternate version progresses smoothly and logically rather than with the release version’s fits and starts and is far more satisfying.

It’s a fascinating glimpse of what happens when an executive focused on supposed marketing concerns rather than the dramatic imperatives of a narrative wrecks what would otherwise be a perfectly good movie. (Well, there are some issues intrinsic to both versions, particularly the seemingly interminable “comic” relief which stops the film dead immediately after Erik kidnaps Camille and kills her mother; three witnesses argue about what language the unseen assailant was speaking.)

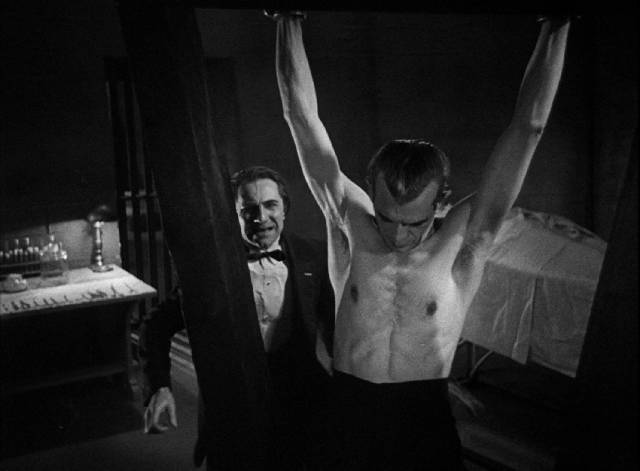

in Edgar G, Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934)

The Black Cat (Edgar G. Ulmer, 1934)

The inclusion of this alternate cut makes Murders in the Rue Morgue the most interesting element of the set, but not the best film. That remains Edgar G. Ulmer’s expressionist masterpiece, The Black Cat (1934), the first of seven movies in which Lugosi appeared with his rival Boris Karloff. Ulmer and co-writer Peter Ruric, with the imminent imposition of the Production Code looming over them, threw in everything that was about to be clamped down on, including Satanism and necrophilia. The Black Cat offers a heady stew of madness and perversion in which Lugosi for once gets the sympathetic role, while Karloff is a psychologically twisted monster.

With the shadow of World War One hanging over the film, the Modernist design of the sets takes on a sinister, inhuman ambience which is amplified by the expressionist cinematography of John J. Mescall. On a train travelling through Eastern Europe, a honeymooning American couple, Peter (David Manners) and Joan Alison (Jacqueline Wells), meet a haunted man named Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi) who describes a terrible slaughter which occurred here during the war. He is returning after eighteen years away, first in the war, then in a notorious Siberian prison. Recently released, he is now going to visit his old acquaintance Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff).

Completing his journey by bus, Werdegast, along with Peter and Joan, is stranded during a rainstorm and the travellers arrive at Poelzig’s mountaintop home late at night. Tensions mount as Poelzig seems to be concealing something while simultaneously taking an unhealthy interest in Joan. His secret is that he took Werdegast’s wife after the doctor vanished during the war and now keeps her dead body preserved in a glass case, while Werdegast’s now-grown daughter is apparently Poelzig’s lover, wandering around the house in an almost somnabulistic state. As if all the creepy sexual undertones weren’t enough, Poelzig is also the leader of a Satanic coven which holds its rites beneath the house. Learning what has happened to his wife and child, Werdegast becomes unhinged, tying Poelzig to a frame in a parody of the crucifixion and skinning him alive.

The young couple flee into the night as a massive explosive charge buried beneath the mountaintop puts an end to all the perverse libidinal energies contained within the Modernist house. As for the title, it’s “explained” by the doctor’s pathological fear of cats which is triggered several times by Poelzig’s pet. Otherwise there’s nothing of Poe at all, not that it matters because The Black Cat is one of the most magnificently unhinged movies from the golden age of early ’30s horror, with Lugosi and Karloff each giving one of their best performances.

The Raven (Louis Friedlander, 1935)

The third movie in the set comes nowhere near that standard, or even rises to the level of Murders in the Rue Morgue. The Raven (1935) squeezes a lot more Poe into a melodrama more typical of the period, with echoes of MGM’s superlative Mad Love (Karl Freund, 1935), which was released just a few days after the Universal film. It was directed by Louis Friedlander aka Lew Landers, a prolific maker of B-movies without any particular sense of style, and once again teams Lugosi with Karloff, who here plays second fiddle to Lugosi’s mad doctor Richard Vollin.

When young Jean Thatcher (Irene Ware) is seriously injured in a car crash, her father Judge Thatcher (Samuel S. Hinds) pleads with Dr. Vollin to come out of retirement to save her. Initially unwilling, Vollin eventually agrees and after Jean’s recovery, he becomes romantically obsessed with her (like Peter Lorre’s Doctor Gogol in Mad Love). When he declares his feelings, a grateful Jean and her protective father are repelled.

Angry at this rejection, Vollin is fortuitously handed the means for revenge when criminal Edmond Bateman (Karloff) shows up demanding that the doctor give him a new face. Bateman believes his criminality is the result of having been called ugly all his life and that he will be able to live a decent life if only he’s made better looking. Vollin says he’ll help if Bateman agrees to exact revenge for him on the Thatchers. Bateman refuses, but Vollin operates anyway.

When the bandages come off, Bateman discovers he’s been monstrously deformed and Vollin says he’ll only reverse what he’s done if Bateman agrees to help him get revenge. Bateman reluctantly agrees and takes the role of Vollin’s servant when Jean, the Judge and Jean’s fiance Jerry (Lesley Matthews) are invited to a dinner party only to find themselves trapped in the torture dungeon Vollin has installed beneath his house, filled with devices from Poe’s stories – a pit, a pendulum, a shrinking room. It turns out that Bateman may not have been a bad man simply because he was ugly, because even though Vollin made him hideous, he sacrifices himself to save Jean and Jerry.

The Raven seems more superficial than the other two films in the set, lacking their air of overheated imagination and unwholesome obsession, its narrative thrown together out of a grab-bag of generic elements. Which is not to say it isn’t entertaining, just that it’s rather impersonal and less memorable.

All three films look very good on Eureka’s disks; considering the age of the source materials, visible damage is fairly light. Sound is passable, but doesn’t fare quite as well. There are commentaries on all three films – surprisingly, two on The Raven – and several audio extras (a couple of radio plays and Lugosi reading “The Tell-Tale Heart”), plus video essays by Lee Gambin (a rambling, unfocused piece on cats in movies) and Kat Ellinger (on “American Gothic”). Kim Newman chats enthusiastically for half-an-hour about Poe, Lugosi and the creativity of early ’30s horror. The booklet has essays by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Jon Towlson about Lugosi, the films and censorship, plus the reprint of Tim Lucas’ Video Watchdog piece.

It’s a great set, with fine transfers of all three movies, informative supplements and the very welcome inclusion of that re-edited version of Murders in the Rue Morgue, which will definitely be the choice whenever I get the urge to watch the film again.

*

Apart from these recent and in-coming releases, I have a backlog from Eureka (as well as the BFI, Arrow, Indicator, Vinegar Syndrome, Severin). As always, this is a mix of upgrades replacing previously owned editions and new acquisitions of movies I’ve seen but haven’t owned on disk, as well as movies I haven’t seen before:

Peter Watkins’ Edvard Munch

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (the MoC 90th anniversary set with all available versions)

Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah: The Four Sisters

Raymond Bernard’s Les Miserables & Wooden Crosses

Elaine May’s A New Leaf

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Tokyo Sonata

John Carroll Lynch’s Lucky

Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc

Sam Fuller’s Fixed Bayonets!

Tobias Nolle’s Aloys

Comments