Seeking cinematic truth: two new Criterion Blu-rays

“This film must be susceptible to analysis, and yet it must be as unfathomable as the cosmos.” – William Greaves, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm production notes

To state the obvious, cinema is artifice, a constructed representation of the world. But as with any art, serious practitioners use it as a vehicle to discover or reveal some kind of “truth” about human experience. There are many paths to these truths, of course, as illustrated by the varieties of art, literature, philosophy, science and religion manifest throughout history. Seemingly by chance, two Criterion releases this month provide radically contrasting examples of filmmaking in that ongoing quest. Their diametrically opposed approaches are both nonetheless emotional, revelatory, and ultimately haunting in what they discover and in the questions they leave unanswered, an acknowledgement that “truth” remains elusive.

Both Robert Bresson’s Mouchette (1967) and William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968) were made at a time when the western democracies were undergoing tumultuous social and political upheavals, yet the former contains no sign of the approaching chaos of 1968 in France, while the latter is rooted in the civil rights and anti-war struggles which were reshaping the U.S. in the mid-’60s. Bresson’s film has a timeless quality, adapted from a literary source (a 1937 novel by Georges Bernanos, who had also provided the source for Bresson’s earlier Diary of a Country Priest [1951]); Greaves’ work is rooted in film itself, the machinery of cinematic representation and its intersection with the varying attitudes and intentions of the actors and technicians who have come together to shoot this movie in particular.

*

Mouchette (Robert Bresson, 1967)

I confess that Robert Bresson intimidates me. He has accrued such an aura of respect and admiration among critics and film historians that I always fear I’m not up to the task of appreciating his work with sufficient nuance and depth. I’m not sure whether I accept his famous belief in non-acting as a more truthful path to authenticity than a reliance on the skills of trained actors. Sometimes it seems to work, at others not so much – I recall watching L’Argent (1983) years ago and being impressed by its intricate construction and frustrated by its clumsy, flat performances. In a couple of supplements on Criterion’s new Blu-ray (both carried over from the 2007 DVD), it’s fascinating to watch him shape every movement, every gesture, every look and (non)expression of the cast, moulding them moment by moment without any reference to emotion or inner psychological detail.

In his previous film, Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), Bresson had depicted rural France as a world of relentless cruelty and violence, as seen from the point of view of a donkey whose life is one of almost unrelieved suffering. There are tender moments involving a young woman named Marie (Anne Wiazemsky), who herself lives a life of hardship and cruelty. The following year, in Mouchette, Bresson revisits this same world sans donkey, focused now on an adolescent girl living in poverty, looked down on by her schoolmates and adults alike. Her father lives by petty crime (smuggling illicit booze) and her mother is dying of cancer, leaving Mouchette (Nadine Nortier) to be a substitute caretaker for a baby brother.

Mouchette is alert and observant, forced by circumstances to gauge everyone around her with suspicion. She observes criminality, sexual conflict, pervasive alcoholism and hypocrisy and is filled with contempt for this corrupt society. She is constantly judged by people whose own moral position is dubious at best. The poacher Arsene (Jean-Claude Guilbert) and the gamekeeper Mathieu (Jean Vimenet) are engaged in a long-running conflict over Arsene’s traps, a conflict which is exacerbated by their rivalry for the attention of barmaid Luisa (Marine Trichet), who takes pleasure in provoking Mathieu in public, in front of his wife (Marie Susini). That rivalry reaches its climax on a rainy night in a fight partially witnessed by Mouchette, who believes that Arsene has killed Mathieu.

Arsene takes her to a deserted barroom where he coaches her in what to say to provide him with an alibi. She has no intention of betraying him to the police, her maternal instincts drawn to his vulnerability – a vulnerability amplified when, drunk from guzzling gin, he suffers a petit mal epileptic seizure. But when he recovers, his personality seems changed. He has forgotten the earlier events of the evening, the fight with Mathieu, and becomes aggressive. The night ends with him raping Mouchette, who responds with confusion because her desire to comfort him gets mixed up with awakening sexual feelings. The experience is a brutal, abrupt coming-of-age. She returns home with a new view of the world, an enforced maturity.

Her father and older brother are away and her mother is near death. Mouchette tries to comfort her mother, giving her gin to kill the pain, and clumsily attends to the crying baby. When she turns away to conceal the depleted gin by topping the bottle up with water, her mother quietly dies and Mouchette collapses into exhausted sleep, waking again when her father and brother return.

Going to fetch fresh milk for the baby, Mouchette experiences the world in a new way. Knowing of the death of her mother, people respond with apparent charity which quickly turns to contempt – a shopkeeper gives her coffee and a croissant, then sees her torn blouse and scratches which reveal traces of the rape. She calls Mouchette a slut and the girl leaves. An elderly woman calls her in and offers a shroud for her dead mother and cast-off dresses for Mouchette, a generous gesture which simultaneously emphasizes the girl’s poverty. Mouchette refuses to be grateful and grinds dirt into the woman’s carpet.

I’m not sure how to interpret the film’s ending. Mouchette has proved wilful and resilient during the harsh events of the narrative, but she also knows that she’ll never be accepted by these people, nor does she want their acceptance. This is a corrupt world and its inhabitants mean-spirited and dishonest. But her decision to die rather than to carry on doesn’t entirely convince me. It feels a bit like tragedy imposed by literary conceit … but this is where my uncertainty about my own understanding of Bresson may come into play. With no personal religious beliefs, let alone Catholic ones, I may not be able to grasp concepts of transcendence which seem at odds with the very concrete and powerful material qualities of Mouchette’s life.

Bresson’s approach to performance ensures that Mouchette remains enigmatic even as we identify with her responses to this very material world that she inhabits. Nadine Nortier, whose sole film role this was, is a remarkable presence onto whom it’s almost impossible not to project thoughts and feelings which she resolutely leaves unexpressed under Bresson’s guidance. With almost all of the Bresson films I’ve seen, I have experienced a kind of detached admiration, but here, largely because of Nortier’s (non)performance, I found myself fully immersed in this world, steeped in ugliness and cruelty as it is. The few moments of warmth and pleasure Mouchette experiences point to another possible life, which is perhaps why I want to resist the defeat imposed on her in the end.

The image on Criterion’s Blu-ray, from a new 4K restoration, is rich in contrast and detail, with solid blacks and a pleasing film-like texture. The extras – a commentary from Tony Rayns; Au Hasard Bresson (31:13), a documentary shot during the production in 1967, and an excerpt from the French television series Cinema – are illuminating about Bresson’s process and how the non-professional actors responded to his approach. There’s also the original theatrical trailer which was edited by Jean-Luc Godard, plus a booklet which reprints Robert Polito’s essay from 2007.

*

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Two Takes

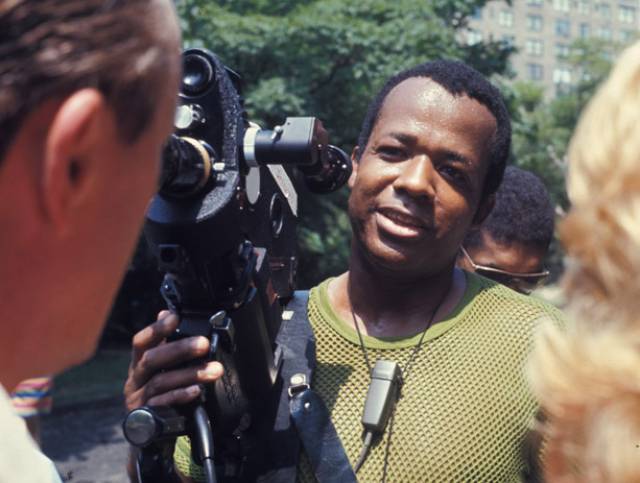

(William Greaves, 1968/2005)

William Greaves, a former theatre and film actor turned documentary filmmaker, eschews the classical formal qualities of Bresson’s work in pursuit of something very different in his radically experimental Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) and its belated sequel Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1/2 (2005). The first time I saw these films, when Criterion released a two-disk DVD edition in 2006, there was a great sense of discovery; I’d never heard of Greaves, although he was a pioneering Black filmmaker who had learned his craft during a ten-year tenure at the National Film Board of Canada (having realized in the early 1950s that there were virtually no opportunities available to him in the States). Inspired by NFB founder John Grierson, Greaves saw documentary as a tool for social change and eventually returned to the States to pursue a career informed by the on-going Civil Rights movement.

Given an opportunity in 1968 to make any film he wanted, he embarked on an experiment which interrogated not only the process of filmmaking itself, but also his own role as director. At that time, the Civil Rights movement, the anti-war movement, hippies and various radicals were all calling into question traditional structures of authority; in cinema, during that period, increasing academic interest and the prominence of the auteur theory developed by French critics and popularized in the States by critic Andrew Sarris in his 1962 essay “Notes on the Auteur Theory” and his 1968 book The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968, had raised directors to a position of primary creative importance – it was the director who made the movie, all others being subordinate. Greaves’ politically informed point of view made him interested in questioning this position, not just in theory but in actual practice.

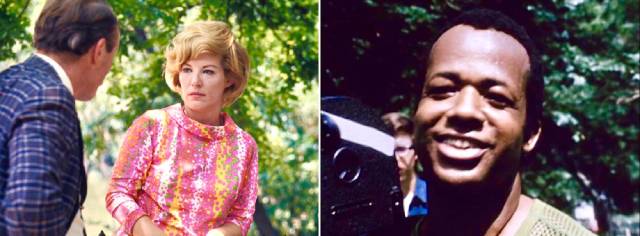

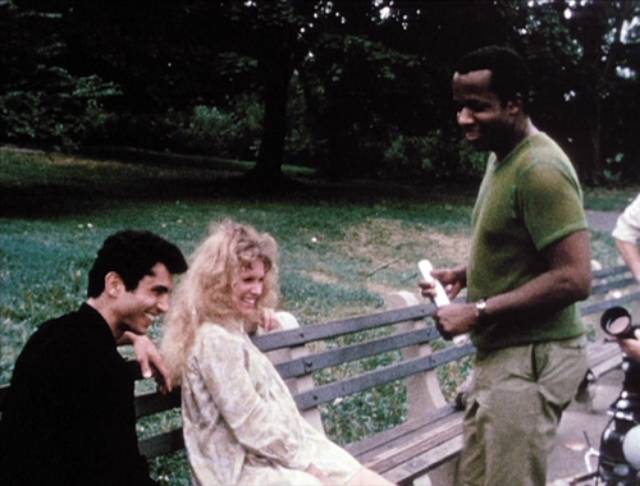

Greaves wrote a dramatic scene, an argument between a middle class couple. It was a deliberately coarse, trite imitation of the kind of thing Edward Albee wrote, and he made it provocative – rife with sexism and homophobia, this is perhaps the first layer of uncertainty; how deliberate or inadvertent are the attitudes embedded in the argument? Then he hired a crew and lined up a number of actors (including a young Susan Anspach) to form pairs for a screen test using the scene. Over a period of several days, this scene was shot over and over again in various parts of Central Park. We get glimpses of each pair of actors before the film settles on one particular couple, Patricia Ree Gilbert as Alice and Don Fellows as Freddie, who are run through the scene repeatedly.

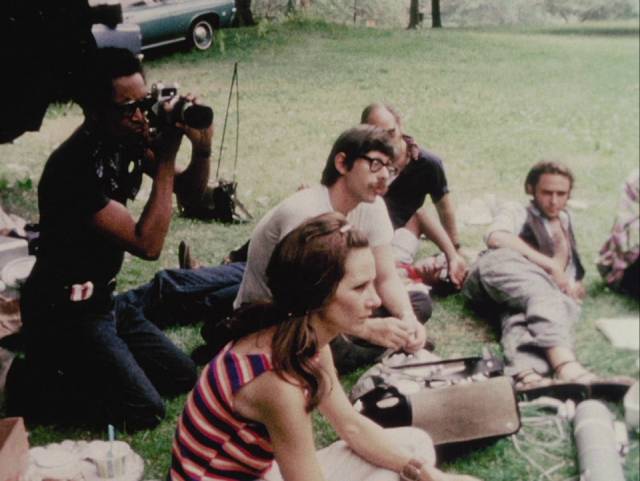

Beyond the banality of the scene, Greaves provides multiple alternative readings as if searching for something he is not himself sure of. The impression of uncertainty he projects provides a second layer which complicates the exercise. Additional layers are created by the use of three separate cameras – one to shoot the actors (the actual “screen test”); a second to shoot Greaves and the actors, observing the director’s process; and a third to step back further to observe the crew who are shooting the scene and the larger setting, which includes passers-by watching the crew work … all together, these elements embody the core of filmmaking (creating the dramatic scene itself) as well as a documentary of the process. For the participants, the purpose appears to be the first level (the scene); for Greaves, what’s important is the larger context, and documenting what he has set in motion.

Greaves’ unspoken intention is to see how far these people will allow him to dominate and manipulate them. He had imagined that the actors would eventually rebel, but what actually happened was something he hadn’t foreseen. Unknown to him, after a couple of days of on-set confusion, members of the crew had a meeting to discuss what was happening, to figure out whether Greaves simply didn’t know what he was doing or whether he had something else in mind which he was unable to communicate clearly. They filmed their discussion with the aim of presenting the material to Greaves at the end of the shoot.

It is during this meeting – in which some defend Greaves and suggest that they must patiently allow things to work out, that they must trust that he knows what he’s doing even if he doesn’t communicate it well – that one crew member looks at the camera and refers to some possible future audience who may eventually watch them discussing the situation; he points out that such an audience can never know whether this discussion is genuine, a spontaneous response to a real situation, or whether it’s actually yet another scene created by Greaves, who may well be sitting just outside of the frame directing them all. The film here reaches an exhilarating level of self-referentiality, a complex meta-cinematic meditation on how movies create a representation or simulacrum of reality which has a reality of its own, separate and distinct from “actual reality”.

The meetings of the crew, these discussions, reflect what was going on in society at the time – echoing various forms of consciousness-raising, both personal and political. They question the traditional structure of filmmaking authority. Although the crew do not ultimately rebel or walk away from the shoot, they do begin to openly question Greaves about his decisions and choices – this is particularly pointed towards the end of the film when the director has Anspach and Andre Plamondon sing their lines as if they’re in a Jacques Demy musical. Asked why from off-camera, Greaves replies that “it’s an idea”, just something he wants to try. With nothing else to go on, the crew indicate that they don’t think it’s a good idea.

By the end of the shoot, Greaves thought that his experiment was something of a failure – until he was given the crew’s surreptitiously shot footage. Here was the revolt he had been trying to provoke, but which hadn’t erupted openly on set. Setting aside ego (the footage is fairly critical of him), he uses the material to structure his film. After all, the crew’s criticism is of the persona Greaves had deliberately created, not of who he actually was or of his larger purpose in conducting the experiment – yet one more level of a complex structure which he had set in motion, simultaneously guiding it and letting go of control.

Finally, it helps to know what that title means. Coined by social scientist Arthur P. Bentley, symbiotaxiplasm refers to a complex network of factors which arise through the social interactions of groups, forces generated by but not intentionally controlled by those immersed in them. Greaves set out to create such a social situation – the shooting of a screen test in Central Park, for the purpose of which a disparate group of actors and technicians were gathered together for several days – and then complicated it with the conception of his own role (as possibly confused or incompetent), documenting it all on film.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One is remarkable on many levels, not least for being an audacious experiment which drew on influences from European filmmaking, particularly the self-conscious deconstruction of film form conducted by the nouvelle vague (the crew’s meetings are reminiscent of Godard’s politicized filmmaking following the uprisings of 1968). This kind of thing was not a familiar practice in the U.S. and that it was being done in this case by a Black filmmaker at a time when there were very few Black directors is even more remarkable.

It’s hardly surprising that Greaves’ film garnered no commercial interest when completed (though perhaps if it had been in French, it might have attracted a student and arthouse audience). Considering it a failure, he set it aside and carried on with his documentary career. It was more than two decades later, when it was included in a retrospective of his work in the early ’90s, that actor and filmmaker Steve Buscemi saw the film and took an enthusiastic interest in Greaves and his work. Take One ends with a title card over a freeze frame of actress Audrey Heningham announcing that Take Two would soon follow (Greaves’ original plan was to make five versions, each focusing on a different pair of actors performing for the screen test, and apparently fifty-five hours of film was shot). Now the idea of making a “sequel” took hold, though it was years before it finally came together, this time under the auspices of producer Steven Soderbergh, with Buscemi taking an active part in the production.

Given that by this time the original experiment had become a known quantity, the question was how to mould the idea into something new. It would be impossible to put together an entirely naive crew at this point, and simply repeating the same experiment with directorial authoritarianism would be redundant. And so Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1/2 (2005) turns its attention to the process of acting, to the complex intersection of the actor’s identity with the character being played.

For the first almost forty minutes, we see something like a recreation of the first film, this time using footage of Heningham and Shannon Baker from 1968, the scene taking on a different inflection with an interracial couple. We see them going through a number of variant interpretations of the scene in different Central Park locations, intercut again with fragments of the rebellious crew discussing the situation … but then the film jumps to the present (and from the original 16mm film stock to video). We see Heningham in a cab on New York City streets, while Baker waits at the edge of the park, pacing and glancing repeatedly at his watch. And then the cab arrives and they greet one another warmly, old friends who haven’t seen each other for a long time.

It takes a while to decipher this reunion – two actors who worked together thirty-five years ago just now catching up? or husband Freddie and ex-wife Alice meeting again years after the divorce which followed that argument in the park in 1968? What follows continually slips between these two registers as the actors, guided by Greaves, recreate those long-ago characters and extend their emotional conflicts into the present. Alice has long lived in Europe, where she has a successful singing career, while Freddie is dying of AIDS, having been a drug addict, now involved in helping others overcome addiction.

Alice has returned to New York in response to an urgent call from Freddie; she has agreed to meet him again after all these years, perhaps seeking some kind of reconciliation, believing his death is imminent. But Freddie gradually reveals his motives – after the death of one of the women he had been working with, an addict and prostitute, he has informally adopted the woman’s daughter. Now he is concerned that the girl Jamilla (Ndeye Ade Sokhna) will be left alone when he dies. He wants Alice to take care of her and nurture her potential singing career. Alice is furious – she’s had no children of her own, having aborted the child she might have had with Freddie (a major element of that long ago argument), and here he’s trying to pass on his own substitute child.

Questions about both characters’ feelings and motives seem to have no clear answers and the scene stubbornly refuses to take convincing shape. At this point, Greaves introduces a psychodramatist (Marcia Karp) into the mix, a kind of coach who steps in and voices what each character is not actually saying in the scene. She functions as a kind of emotional amplifier and irritant, pushing, aggravating … and the scene grows incredibly raw. Again, it’s almost impossible to tell where actor and character begin and end. Anger and painful emotions spill out with such force that the scene breaks down completely. Heningham’s fury appears to be directed at Baker (rather than Freddie) and she finally can’t continue, walking away from the scene.

This is the point at which Greaves steps in. What has happened is rooted in Stanislavski, Strasberg and the Method, the two actors having drawn so deeply on their own inner feelings that the enmity between the two characters has all but consumed them. As in Take One, Greaves anatomizes the inextricable connections between artifice and reality out of which art emerges.

Taken together, the two films are a masterclass in cinematic creation, made by an artist who somehow maintains control while simultaneously being willing to relinquish all control to make space for his collaborators to contribute something which goes far beyond the limits of his own abilities. It’s a remarkable balancing act and the resulting films remain absolutely fresh, offering new insights with every viewing.

Criterion’s Blu-ray improves on the image of the old DVD edition, but no attempt is made to conceal the flaws inherent in the material – 16mm reversal stock is contrasty, with a lot of grain, and there are scratches and exposure issues (as well as reel change marks), all left in because Greaves himself saw these flaws as an integral element of the work. Take 2 1/2 has the additional clash between the older film stock and the flatter image of video. While none of this is elegant, it does add the sense that what matters is everything occurring before the cameras rather than the technical accomplishment.

The new disk duplicates the contents of the DVD – a documentary about Greaves’ fascinating career (1:01:15) from 2006 and a short interview with Buscemi (12:47) about his discovery of the film and the part he played in seeing that the sequel got produced. The booklet also duplicates the previous edition, with an essay by Amy Taubin and notes made by Greaves before shooting Take One which outline his intentions and reflect the resulting film with surprising precision.

*

As different as Bresson’s and Greaves’ films are, they both illuminate ways in which cinematic artifice can create remarkable representations of experienced reality, stirring feelings of recognition and startling flashes of insight and understanding in viewers who are open to their strategies.

Comments