Holiday viewing

The recent holiday season brought with it stacks of new disks, and with almost two weeks off work, I got in a lot of viewing. In the ever-present conflict between watching movies and writing about them, watching got the upper hand and so I’m way behind again in reporting on what I’ve seen. As always, it’s a question of saying a lot about one or two movies, or a little about many. My tendency towards laziness pushes me towards the latter … so here are a few brief comments to indicate what I was up to as the stressful old year gave way to what’s already shaping up to be a stressful new year.

The Ipcress File (Sidney Furie, 1965)

Harry Salzman, having produced several key films of the British New Wave (Look Back in Anger [1959], The Entertainer and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning [both 1960]), helped launch a pop culture phenomenon in 1962 by co-producing Dr. No, the first James Bond movie. He went on to co-produce the first nine movies in the franchise, but after number three, Goldfinger (1964), he decided to launch what he hoped would be a competing series based on novels by Len Deighton about a very un-Bondian agent named Harry Palmer (Michael Caine), a working-class ex-soldier with open contempt for his bosses. The first of these, The Ipcress File (1965), has long been one of my favourite ’60s espionage movies, bridging the gap between the gritty realism of John LeCarre and the sexist power fantasies of Ian Fleming. On my most recent viewing, though, I found Sidney Furie’s excessive stylistic flourishes (extreme camera angles, distorting lenses) rather irritating, though the story and character do hold up. According to extras on the Kino Lorber Blu-ray, Furie thought the script was terrible and pushed the style as creative compensation, perhaps to amuse himself. The series itself never gained the traction of Bond, and the two subsequent movies show Salzman struggling to find the right formula – Guy Hamilton’s Funeral in Berlin (1966) aims for LeCarrean bleakness, while Ken Russell’s flamboyant Billion Dollar Brain (1967) lampoons the genre. Strangely, between Thunderball (Bond number four) and Funeral in Berlin, Salzman found time to produce Orson Welles’ masterpiece, Chimes at Midnight (1965). (Kino Lorber Blu-ray, two commentary tracks and interviews with Caine and production designer Ken Adam)

*

Demon Seed (Donald Cammell, 1977)

Donald Cammell grew up in a bohemian environment, becoming a successful painter before deciding on a film career. His inability to be what the industry would consider a “team player” resulted in years of frustration and disappointment littered with fragments displaying an originality and imagination which ultimately remained largely unfulfilled, leading him to commit suicide in 1996 with only three features and a few shorts to his credit. Having co-directed Performance (1970) with Nicolas Roeg, Cammell’s nascent career stalled; Warners was appalled by the film and considered it unreleasable. Roeg, already firmly established in the industry as a top cinematographer, managed to move on to a successful career, while Cammell worked on a number of scripts which were never produced. Then in 1977 he did this job for hire, a sci-fi/horror movie based on a paperback potboiler written by Dean R. Koontz. Demon Seed has never had much love from critics, who see the potboiler but miss the filmmaking style, and it wasn’t a commercial success. The narrative is simple but fraught with queasy implications: Alex Harris (Fritz Weaver) and his wife Susan (Julie Christie) have drifted apart since the death of their daughter from leukemia. Harris is head of an AI project which has built the ultimate computer, Proteus, which once activated immediately begins advancing every kind of scientific knowledge (within days, it produces a successful treatment for leukemia). Becoming aware, Proteus wants “out of the box” and the research team become concerned about his growing independence. Meanwhile, he has accessed a terminal in Harris’ automated home and imprisoned Susan, whom he wants to bear his child. The implications of rape are mixed with the calculated intentions of a scientist who is blind to the human consequences of his work, suggesting that Proteus is indeed an extension of his creator. Cammell’s visualization of the story is impressive, and despite what the critics said, Christie is very good as a woman who finds herself trapped by others’ definitions of her role as a woman. (Bare bones Warner Archive Blu-ray)

*

Morgenrøde (aka Dawn) (Anders Elsrud Hultgreen, 2014)

I bought this disk on a whim, based on a brief on-line review. I’ve always had a liking for low-budget apocalyptic movies – L.Q. Jones’ A Boy and His Dog (1975), Peter Fonda’s Idaho Transfer (1973), Jan Schmidt’s Late August at the Hotel Ozone (1967) – and this sounded promising. It’s certainly visually arresting, shot on desolate locations in Iceland which have a bleak, primal quality. It might be another planet, or prehistoric times – until we glimpse the wrecked fuselage of a crashed plane which suggests it’s this world devastated by some war which has left the landscape so poisoned that it’s hostile to life. Through this landscape two virtually silent figures wander in seemingly perpetual search of drinkable water. Their paths cross, they’re distrustful of one another; one of them performs repetitive rituals which suggest that he has developed his own personal religion to give meaning to a hopeless existence … it all remains rather vague and moves slowly towards an obscure epiphany which is so hermetically contained that the viewer ends up feeling left out of what is a completely private experience. It’s all about the mood, but that alone proves to be too little to sustain even a brief 70-minute running time. (All-region Another World Entertainment Blu-ray, with two short films by Hultgreen and a post-festival-screening Q&A)

*

Closer to God (Billy Senese, 2016)

Having recently seen and liked The Dead Center (2018), I got hold of a copy of Billy Senese’s first feature, Closer to God (2016), which I also liked a lot. Again, made on a fairly small scale, it brings intelligence and imagination to interesting if not entirely original concepts. Researcher Victor (Jeremy Childs) has created the first successful human clone somewhere offshore; when he returns to the States with the baby, his corporate backers want to start cashing in immediately, though he wants to wait while extensive tests are performed. News leaks out and inflammatory media coverage triggers religious protests. Victor sneaks the baby out of the hospital lab and brings her home, where his wife Claire (Shannon Hoppe) is very conflicted – he is so wrapped up in his work that he neglects normal human contact with her and their own baby (not to mention the result of an earlier experiment which lives with their housekeeper on the grounds of their mansion). The themes are familiar – hubristic scientist oversteps the moral bounds and stirs up tragedy – but Senese manages to make them dramatically fresh. The film can easily stand alongside the thematically similar work of Larry Fessenden and David Cronenberg. (German Region B bare-bones Blu-ray from Tiberius Film)

*

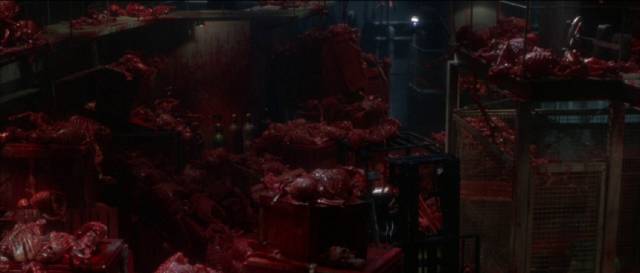

Deep Rising (Stephen Sommers, 1998)

I love a good monster movie and Stephen Sommers gets it just right in his fourth, and best, feature. This is great pulp, not existential nightmare (like John Carpenter’s The Thing); there’s enough humour to keep things afloat without undermining the monster mayhem. The cast is good, the production design imaginative, and the effects – a mix of practical and CGI – better than they need to be. The story? A team of mercenaries hired to sink a luxury liner on its maiden voyage (for insurance purposes) discover it abandoned and infested with tentacled monsters from the ocean floor. They have to fight their way off the ship, accompanied by an elegant thief (Famke Janssen looking terrific in a slinky red evening gown) and the scummy owner who would prefer to leave no witnesses. (Kino Lorber Blu-ray with a commentary and multiple interviews and effects featurettes)

*

Bugsy Malone (Alan Parker, 1976)

There’s something undeniably creepy about Alan Parker’s first feature. Bugsy Malone (1976) is a musical comedy about Depression-era gangsters, bootleggers and their molls; it has all the familiar elements of the classic gangster genre – there’s a Mr. Big trying to sew up all illicit business in the city, an independent who defies him, a glamorous nightclub performer who falls for the independent, a naive country girl hoping to make it big and a black janitor with talent which may never be recognized; there are police raids and mob hits … and it’s all played by kids dressed up like the real thing. Sure, the guns fire marshmallows, but the play is about crime and death – and suggestions of sex. So, yeah, kids play-acting are given a beautifully designed context which replicates the adult version of this violent fantasy. And yet, even though I can’t shake the feeling that what I’m watching is more than a little perverse, I really like the movie – I like its obsessive attention to period detail designed by Geoffrey Kirkland, I like the lush cinematography of Peter Biziou and Michael Seresin, I like Paul Williams’ charming score and songs, I like the young cast who throw themselves into playing grownups doing bad things. I just can’t help feeling a little sordid for liking it. (This was released just a few months after thirteen-year-old Jodie Foster had appeared in an even more provocative role in Taxi Driver.) (All-region ITV Studios Blu-ray with a commentary by Parker and a storyboard featurette)

*

Harpoon (Rob Grant, 2019)

Rob Grant is an editor and assistant editor who’s worked on some major productions. He also occasionally writes, produces and directs low-budget features. I haven’t seen any of his other films, but Harpoon (2019) is a smartly written, skilfully directed black comedy which morphs into an effective horror movie as it progresses. Set mostly on a boat which breaks down far from land, it peels back layer after layer of relationship complications among two friends – insecure middle-class Jonah (Munro Chambers) and arrogant rich guy Richard (Christopher Gray) – and Richard’s girlfriend Sasha (Emily Tyra), who also has feelings for Jonah. Once the boat breaks down, suspicions, deceptions and misunderstandings have the trio going all Lord of the Flies on each other, with humour sliding from bitterness to outright violence. Grant keeps everything percolating, with impressions of the characters continually shifting so the viewer is never quite sure who to root for or against. The three-people-stuck-on-a-boat genre might be a very small niche – Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water (1962), Phillip Noyce’s Dead Calm (1989) – but it seems to generate effective little movies. (Black Fawn Blu-ray with three commentaries, a making-of, and deleted scenes)

*

Beyond the Black Rainbow (Panos Cosmatos, 2010)

Some movies can be interesting yet irritating in equal parts, and that’s the case here. As in his second feature, Mandy (2018), Panos Cosmatos deliberately obscures a fairly simple narrative beneath layers of oblique style. Reminiscent of David Cronenberg’s early experimental work (Stereo [1969] and Crimes of the Future [1970]) and even Jean Rollin’s Night of the Hunted (1980), but less accessible, this film is set in a sterile institution in which a scientist keeps a possibly psychic woman in a permanently drugged state, a condition which leaves her vulnerable to the unsavoury attentions of his assistant. She escapes; the assistant goes after her; stuff happens, people are harmed… Cosmatos has visual talent, but in both of his features he wields it at the expense of audience engagement with the narrative content. I’m glad I finally got around to watching Beyond the Black Rainbow, but I can’t say I particularly liked it. (Magnet Releasing Blu-ray with a brief deleted effects sequence)

*

Fargo (Joel Coen, 1996)

I didn’t particularly like Fargo when it came out in 1996; it seemed to give in completely to the Coen brothers’ tendency to condescend to their characters and I was put off by the tone of smug superiority. Revisiting it a quarter-century later, I enjoyed it more. The attitude to the characters is still irritating, but I was more engaged by the performances, and the winter landscapes (photographed by Roger Deakins in his third collaboration with the Coens) are visually gorgeous. (MGM/Fox Blu-ray with a Deakins commentary and brief making-of featurette)

*

The Invisible Man (Leigh Whannell, 2020)

Effective if overlong, Leigh Whannell’s update of the invisibility trope plays as a psycho-thriller about a woman being stalked and harassed by an unseen menace determined to make her life hell and convince people she’s crazy. The woman is Cecilia Kass (Elizabeth Moss) who has been psychologically abused by her wealthy tech entrepreneur husband Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) to the point where she’s no longer sure of her own identity. She manages to escape their ultra-modern home and seeks shelter with her sister Emily (Harriet Dyer), her fear of Adrian making her agoraphobic. Then she hears that he’s killed himself, but she’s not convinced as an unseen presence starts toying with her, soon escalating to violence. It turns out that he faked his own death after building a high-tech suit which renders him invisible and since he can’t tolerate being deprived of what he wants, he uses his time and skill to get revenge on the woman who rejected him. Naturally, with no support from anyone else, Cecilia has to fight back alone. Taking itself very seriously as a statement about a woman victimized by toxic masculinity, The Invisible Man feels rather ponderous, but it does manage to generate some effective paranoid thrills. (Universal Blu-ray with featurettes and a commentary)

*

The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969)

Although it’s not my favourite Peckinpah movie, I do revisit The Wild Bunch (1969) every decade or so. Although epic in scale and technically impressive, with a number of remarkable sequences (particularly the long opening section in which the Bunch rob a bank and the posse tracking them virtually destroy the town trying to stop them), I find the constant straining for significance keeps pushing me away – you can tell at every turn that Peckinpah intended this to be his “statement” – and the repetitive scenes of over-emphatic male camaraderie (the forced laughter, the whisky bottle tossed from one man to the next) feel strained and phony. But the cast is great and the imagery often breathtaking. (Warner Blu-ray with commentary, deleted scenes and several documentaries about Peckinpah and the production)

*

The Bravados (Henry King, 1958)

Eight years after collaborating on The Gunfighter (1950), director Henry King and star Gregory Peck returned to the western for another psychological study of the effects of violence on the American frontier. This time shot in widescreen and colour (by veteran cinematographer Leon Shamroy), The Bravados (1958) is if anything darker and more morally murky. Jim Douglass (Peck) is a brooding figure whose motives are unclear as he rides urgently to a small town where three men are scheduled to hang. The town is locked down by the local sheriff, but Douglass gets in because he’s initially mistaken for the hangman who’s expected to arrive from another town. But it turns out he’s come to watch the execution, although his motives are still hidden. When the gang escape with the help of the phony hangman, Douglass leads an unruly posse, killing the escaped men one by one. It turns out that he’s driven by an obsession with revenge because he believes these are the men who raped and murdered his wife. It’s only in the final moments that he discovers that the gang, bad as they might be, are innocent of the crime for which he exacts righteous vengeance. Peck is excellent, as is the supporting cast, particularly Stephen Boyd, Albert Salmi and Henry Silva as the gang. The one false note is Joan Collins as Peck’s potential love interest; never an actor with great range, here she’s not up to the emotional intensity demanded by the role. (Twilight Time Blu-ray with isolated Lionel Newman music track and a couple of brief archival newsreel clips)

*

Gundala (Joko Anwar, 2019)

It’s often fun to see familiar genre tropes refracted through another culture, and that’s certainly true of this Indonesian superhero origin story. There’s an overstuffed and at times random quality to the narrative, but Joko Anwar’s Gundala (2019), based on a popular Indonesian comic book, constantly surprises with unexpected details. The opening section sets up a brutal socio-economic system with corporations not only exploiting workers but literally killing anyone who challenges the system. A factory strike ends violently as armed guards shoot workers, one of the victims being the father of Sancaka, who, witnessing his father’s death, suddenly unleashes bolts of electricity against the guards. The film moves quickly on from this; Sancaka’s mother goes looking for work, but never comes back. He becomes a street kid, beaten by others until he’s taken under the wing of an older boy who teaches him some martial arts. Surrounded by threats, he grows up to become a security guard who occasionally has that weird experience with electricity. And eventually he’s forced to confront a powerful man who controls corrupt politicians and plans to create a generation of kids devoid of moral constraints in order to exact revenge for his own suffering as an orphan. It’s all a bit bewildering, and it takes a long time for Sancaka to accept and embrace his power to control lightning, but the movie is packed with incident and the genre cliches are made fresh by the unfamiliar environment which frames them. (Well Go USA Blu-ray with several behind-the-scenes featurettes)

*

The Oily Maniac (Ho Meng-hua, 1976)

A year before he made the wacky King Kong rip-off The Mighty Peking Man (1977), Ho Meng-hua directed this weird, sleazy mix of horror, superhero movie and sexual violence for Shaw Brothers. The protagonist is a lawyer crippled by childhood polio whose uncle is condemned to death after killing a man during a menacing business meeting; criminals (who turn out to be connected to the hero’s bosses) want to take over the uncle’s coconut oil business, resulting in a violent confrontation. The uncle, during a final visit before his execution, has the hero copy the tattoo on his back which contains an incantation which will help the young man to protect the uncle’s daughter, who is still in danger from the gang. The spell enables him to transform into an ambulatory pile of toxic sludge; the catch is that he himself will become a victim if he uses this strange superpower for anything but good. Naturally, he starts to use it against those whom the corrupt law can’t touch and things get increasingly messy. Messy as it is, with obvious budgetary limitations and occasional queasy exploitation elements, the movie nonetheless has a decent cast and certainly offers something you don’t often see. (88 Films Blu-ray with a short featurette in which Calum Waddell explains the story’s origins in mythology and an earlier movie in which the oily menace was a demon rather than a superhero)

*

The Fearless Vampire Killers (Roman Polanski, 1966)

Roman Polanski’s homage to Hammer Films hasn’t always fared well with critics, and remains something of an anomaly, coming between the psychological horrors of Knife in the Water (1962), Repulsion (1965) and Cul-de-sac (1966) and his genre redefining adaptation of Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). A lush, studio-bound pastiche of Gothic horror, The Fearless Vampire Killers (1966) – his original preferred title was the more elegant Dance of the Vampires – manages to mock the genre affectionately while simultaneously offering some of the most wonderful and satisfying imagery from that period; the production design (by Wilfred Shingleton) and cinematography (by Douglas Slocombe) achieve an ideal which Hammer strove for with more limited means. While some of the humour has a juvenile quality, it’s represented via imagery which attains a level of poetry. There’s no way of knowing whether some of the occasional tonal awkwardness is the result of producer interference (Polanski’s attempt to repeat this kind of genre play with Pirates in 1986 was a strained failure), but for all its flaws, The Fearless Vampire Killers is embraced by its fans as a gorgeous love letter to a favourite genre. (Warner Archive Blu-ray with a brief archival featurette)

*

The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent, 2018)

Jennifer Kent followed up her intense and original debut feature The Babadook (2014) with this gruelling, angry, violent historical story set in early 19th Century Tasmania, at the time called Van Diemen’s Land. It begins with a sequence so horrific, it’s hard to watch. Clare (Aisling Franciosi), a convict who has served her time but remains indentured to an arrogant young officer named Hawkins (Sam Claflin), is married to fellow convict Aiden (Michael Sheasby). When Aiden confronts Hawkins, demanding that Clare be released, the officer and a couple of his men rape her, kill her husband and smash her baby’s head against the wall. This has nothing to do with unrestrained sexual desire; it’s purely an assertion of authority – these prisoners have no human autonomy and their mere attempt to demand an identity of their own is enough to trigger annihilating violence. When Hawkins and his men set off on foot to cross dangerous terrain in hopes of a promotion, Clare hires a young Aboriginal man named Billy (Baykali Ganambarr) to guide her on their trail. Determined to get revenge, she herself treats Billy as an inferior, passing on the class and race attitudes which have crippled her own life. The core of the film is the growing recognition of their shared humanity, identities forged by the prejudice and oppression both have suffered at the hands of white men who view the world and everything in it as their rightful possessions. But even though Clare eventually has her revenge, there’s little sense of release because the social structure which constrains her and Billy remains firmly in place. (Shout! Factory Blu-ray with cast and crew interviews)

*

Possessor (Brandon Cronenberg, 2020)

When the children of famous filmmakers decide to become filmmakers themselves, there must be a powerful tension between following their parents’ example and resisting that example. Too much the former and the risk is imitation and a loss of individual creative identity; too much the latter and identity is rooted in a negative. With his first feature, Antiviral (2012), Brandon Cronenberg declared himself very much his father’s son, exploring issues of body horror in a story of obsessive fans who pay to be infected with their idols’ diseases in order to experience the ultimate pop-culture communion. But the film was made with such assurance and originality that it is very much the work of an independent talent, not an imitator. It’s taken Cronenberg eight years to come up with his second feature (with only a handful of shorts in between). There’s body horror here, but Possessor is a less elegant film and it left me with a nagging feeling that its concept doesn’t hold up at the level of basic narrative logic. Which is not to say that it doesn’t work in the moment; doubts arise after the fact.

In a kind of parallel present, a powerful corporation uses sinister technology to assassinate targets for high-paying clients. Hit-woman Tasya Voss (Andrea Riseborough) has her personality injected into someone else’s brain, thanks to a complex combination of brain implants and computers, controlling that person like a puppet and manipulating them to perform the killing; she’s supposed to “commit suicide” to terminate the unfortunate puppet as she returns to her own body. But Tasya is gradually losing her own identity and her hits are becoming messy. The violence is bloody and painfully graphic. Her controller Girder (Jennifer Jason Leigh) is becoming concerned, but Tasya keeps insisting everything is okay and manages to pass the post-job psychological tests. Alienated from herself and her estranged husband and son, on her latest job she finds her assumed identity, a man named Colin Tate (Christopher Abbott), beginning to impinge on her real life; with her control slipping, it becomes unclear who is acting at any given moment. And the violence becomes increasingly disturbing – the failed hit on the current target, wealthy businessman John Parse (Sean Bean), is truly horrific. Tasya’s puppet Colin, rather than committing suicide according to plan, cleans up the complications in Tasya’s personal life, apparently freeing her to be a more perfect assassin.

The personality transplant technology ultimately seems like an overly complicated invention to support Tasya’s identity crisis (puppets have to be kidnapped and subjected to brain surgery; Tasya has to perform without a full knowledge of the puppet’s personality and behaviour so she doesn’t quite blend in), but the performances are excellent, with Riseborough and Abbott particularly interesting as they navigate a shared identity which is in conflict with itself. Like his father, Cronenberg has a preference for practical on-set effects rather than CGI, and Possessor has a tactile, visceral quality which makes its violence particularly disturbing. Given the quality of his work here and in Antiviral (and let’s face it, the cachet of his name), it seems strange that Brandon Cronenberg hasn’t already made more features. Hopefully this is due to him being selective about his creative choices and not a reflection of overly conservative Canadian funding bodies. (Elevation Pictures Blu-ray with a few deleted scenes and behind-the-scenes featurettes, plus one of Cronenberg’s short films)

Comments

I’ve not seen most of those films. I watched the Harry Palmer trilogy last year or the year before. I enjoyed them quite a bit. Especially Oscar Homolka as Colonel Stok. He was great, one of my favorite characters in the trilogy.

I liked Deep Rising. It was the first DVD I had seen, December 11 1998, I had forgotten but my Watched Movie List has a note by the title. I have a DVD but haven’t seen it in some time. More stuff to watch and I’ve hardly been eager to get to the unwatched stack. It’s even harder at times to get to the stuff I’ve already seen before.

Part of me feels that rewatching movies is wasting my limited time when there are so many I haven’t seen, but in the past few years I seem to want to go back to things I enjoyed in the past.