Indicator in a box

The Fu Manchu Cycle (Various, 1965-69)

In a recent post, I ended with Indicator’s edition of Max Ophuls’ domestic noir, The Reckless Moment (1949). On an entirely different cinematic plane, the company has collected in a lavish box set all five of the Fu Manchu movies written and produced by Harry Alan Towers in the late ’60s. Probably the most interesting thing about the series is how the conception of the character and his fictional world evolved in four brief years under the direction of three different filmmakers. Created in 1913 by writer Sax Rohmer (Arthur Sarsfield Ward), Dr. Fu Manchu drew on then prevalent Western fears of “the Yellow Peril”, essentially the perceived threat of resistance by the Chinese to European and American colonial oppression in the East. As a villain, he was exotic and determinedly “other”, using insidious poisons and assassins to carry out his plans, rather than modern technological weaponry. Beginning in local resistance, Fu Manchu eventually developed a worldwide criminal organization whose aim was to restore China to imperial dominance. The inherent racism of the conception apparently took on interesting tones as Rohmer continued writing the books and stories until his death in 1959, with Fu’s organization fighting both fascism and communism, both of which posed a threat to his plans.

Despite evolving attitudes which were already making such characters problematic by the ’60s, Towers – a prolific and successful writer-producer for radio and television – saw Rohmer’s books as a viable source of material to compete with the popular James Bond movies which had so recently become successful around the world. Although he couldn’t wield Bond-sized budgets, his business savvy and the decision to hire Don Sharp (whose recent work for Hammer – Kiss of the Vampire [1963] and The Devil-Ship Pirates [1964] – and Lippert – Witchcraft [1964] and Curse of the Fly [1965] – proved him adept at both period films and low budget production) resulted in a movie which seemed far more opulent than it had a right to be.

Fu Manchu (Christopher Lee) is executed in the opening scene of The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), ceremonially beheaded in the courtyard of a Chinese prison under the watchful eye of British officer Nayland Smith (Nigel Green). But back in England Smith confesses to his companion Dr. Petrie (Howard Marion Crawford) that he’s uneasy; hints and rumours from various parts of the world suggest that the influence of Fu Manchu is still active. Of course, it’s not long before we learn that the man we saw beheaded was an actor who merely resembled Fu and the villain is hard at work developing a deadly chemical weapon made from a certain Tibetan poppy. With the villain kidnapping scientists to help in his work, Nayland Smith has to race against time to avert disaster.

The Smith-Petrie pairing points to Rohmer’s inspiration in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories – and as Tower’s series progresses, Crawford gradually morphs into the bumbling comic foil familiar from the Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes movies. Although London remains a bit underpopulated, Sharp does an excellent job of evoking the 1920s with a judicious use of locations and props, and the film’s key set-piece is executed with chilling effect as a small coastal town is sprayed with Fu Manchu’s deadly chemical agent with people dropping instantly in their tracks. Later Nayland Smith and various police and military authorities walk through the town and, even on this small scale, it has an authentically apocalyptic feel.

The chase ends up in Tibet where Smith and a small group of adventurers infiltrate Fu Manchu’s stronghold and blow up the supply of deadly poppies. Over the image of the explosion, Fu’s face appears and he swears he’ll return … which he did the following year in The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966). Although Sharp was once again directing, the budget was smaller and the period detail was shakier. The loss of Nigel Green, who had been such an authoritative opponent in the first film, also makes the sequel weaker. The new casting of Douglas Wilmer, whether intentionally or not, hammered home the fact that Rohmer was imitating Doyle because just the previous year Wilmer had starred in an excellent series of BBC Holmes adaptations. Here, he still seems to be playing Holmes rather than a forceful military man.

Apart from these changes, the biggest problem with the sequel – and the others to follow – was Towers’ script, which is essentially a retread of the first film. Fu wants a super weapon to help him take over the world, check; he kidnaps renowned scientists to develop it for him, check; Nayland Smith follows the clues to Fu’s secret lair, check; the base is blown up, yet Fu swears to return … check, and check again. It’s a formula Towers uses again and again, with diminishing returns. Apparently he bought the rights to the character but not to Rohmer’s actual books, so he had to invent his own stories – and it seems he really had only one story, which he used for all five films. Despite ever-diminishing budgets, perhaps the movies might have fared better if he’d been willing to pay other writers to come up with scripts…

The sense of period deteriorates further in the third film, The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), with Sharp replaced by Jeremy Summers, most of whose work was for television (though his 1963 Tony Hancock feature The Punch and Judy Man has been a favourite since I first saw it more than fifty years ago). Fu’s plans are scaled back in accordance with yet another budget reduction. In place of the second film’s death ray, here the villain is using plastic surgery to replace the various heads of Interpol – including Nayland Smith, whose doppelganger kills his housekeeper, leading to a murder trial and execution. The real Smith is spirited away to Fu’s hideout while his mute double seems to fool everyone. This signals one of Towers’ big failings with the series, progressively weakening Fu’s nemesis; without a strong opponent the villain himself is diminished.

As before, Fu swears to return after apparently being destroyed – a device which begins to feel like a joke. But, yes, he reappeared the next year in The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968). By now, there’s no sense of period and Fu seems completely disconnected from his former self – he’s a generic villain who would have been equally at home in an episode of Get Smart. He now hangs out in South America where he’s discovered yet another deadly poison, this time snake venom with which he somehow infects women who are able to pass it on with a kiss. This device is right up the alley of the series’ third director, Jess Franco, with whom Towers established a partnership which would last several years. In some ways, Franco was a perfect fit with his talent for banging out movies in no time at all for almost no money at all. But the final two Fu Manchu films look pretty threadbare, particularly in comparison to the way the series began.

Fu sends one of his poisonous assassins to London, where she kisses Nayland Smith (now Richard Greene, even less imposing than Wilmer), who is immediately struck blind and destined to die a horrible death in days. It’s up to the bumbling Dr. Petrie to get him to South America and the antidote in time. On the way, they run afoul of a gang of bandits out of a cut-rate spaghetti western. The plan to send poisonous women out into the world to kiss leaders and influential people to death, thus paving the way to world domination, is an absurd idea even compared to death rays and deadly poppies, and the whole movie feels rushed and somewhat shoddy.

But not as shoddy as the fifth and final episode, The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969), again directed by Franco – well, at least in part, because large chunks are stock footage from previous films (particularly The Brides of Fu Manchu) and, most egregiously, an opening section uses the sinking of the Titanic from Roy Ward Baker’s A Night to Remember (1958) and later a dam being destroyed comes from Ralph Thomas’ Campbell’s Kingdom (1957).

The plot has Fu Manchu hunkered down in a castle in Istanbul from which he intends to freeze the world’s oceans. But of course he has to kidnap a scientist to help and that gets the attention of Nayland Smith (Greene again) and Interpol. There’s a completely gratuitous and rather lengthy sequence in which the scientist requires a heart transplant in order to continue his work for Fu, and Franco lingers over the surgery. It doesn’t help much … the series has obviously reached a point of exhaustion from which it could never recover. Despite Fu’s promise to return, this time he didn’t.

The elephant in the room, of course, is the casting of Christopher Lee as Fu. By the mid-’60s, this kind of racial drag was already problematic and today it’s an embarrassment no matter how much gravitas Lee managed to inject into the role. Essentially, his Fu is just Chung King transplanted from Terror of the Tongs (1961) and invested with more ambition. Joseph Wiseman’s Dr. No from the first Bond film (1962) had obviously been modelled on Fu, but he was toned down considerably; Lee goes full-bore with the makeup and physical mannerisms (though thankfully he eschews the common accent usually given to Chinese characters in such movies). It seems to have been the diminishing budgets and Towers’ increasingly threadbare scripts that made Lee’s Fu less of a blatant racial stereotype and more of a cartoon villain in the later movies.

Actor Tsai Chin later regretted her appearance in the series as Fu’s sadistic daughter Lin Tang, conflicted about contributing to negative stereotypes of her race, though at the time there weren’t many roles for a Chinese actor in England, even one who had studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. She stands out as one of the few actual Asians in the films’ casts.

While the movies are pulp entertainment of rapidly declining quality, Indicator has given them excellent transfers and added plenty of supplements, including commentaries, new and archival interviews with members of the cast and crew, introductions by BFI curator Vic Pratt, discussions of Rohmer, the novels and the adaptations by Kim Newman, Stephen Thrower, Jonathan Rigby and Christopher Frayling, plus two episodes from silent serials based on the novels. There’s also a feature-length version of a Children’s Film Foundation serial directed by Jeremy Summers. But perhaps the most engaging extra is a lengthy interview with writer-producer Harry Alan Towers from 2008 which covers his entire career. I’d always imagined him to be something of a hack, pumping out cheap and often shoddy exploitation movies (an impression gained from reading quite a few reviews back in the day of his collaborations with Jess Franco – the Fu Manchu movies as well as a series of Franco adaptations of De Sade stories), but he comes across as a likeable character, cultured and intelligent, who turned to film production after a long and productive career in radio and television which involved an impressive array of connections, not least with Orson Welles who partially funded some of his great ’50s independent features by working for Towers as an actor and/or narrator on various series.

*

in Don Siegel’s The Lineup (1958)

Columbia Noir Vol. 1 (Various, 1945-58)

What actually constitutes film noir has been a subject of debate ever since French critics coined the term when they began seeing American movies again in the years following World War Two. They detected something different coming from Hollywood, something darker, more cynical. Was it a style? Was it an actual genre with its own formalized themes and narrative tropes? In the three-quarters of a century since the term took hold, it still can’t be completely pinned down – it’s one of those things that “we know it when we see it”, which means to some degree it remains a matter of personal taste and judgment, ready to be applied in areas beyond its original inspiration. Although it began with crime stories and camerawork rooted in German Expressionism – all chiaroscuro lighting, characters lost in shadows which reflected their moral confusion – it eventually came to be applied to widescreen colour movies, to westerns, to dramas about business… In other words, film noir is a category of exceptional flexibility.

And having said that, I’ll suggest that few of the films in Indicator’s Columbia Noir Vol. 1 box set are really noir. In my personal opinion, of course. Of the six, two are about criminal investigations (one actually an offshoot of a TV cop show), one is a father-son drama with a business setting in which conflict arises from dad’s involvement with organized crime, one is a heist movie, and another a World War Two espionage story – with only one focused on a hapless guy dealing with his own inner demons as he’s seduced into crime by a femme fatale. Which is not to say that the movies aren’t entertaining, just that it seems a bit forced to lump them together as noir.

Escape in the Fog (Budd Boetticher, 1945)

Budd Boetticher began his directing career at Columbia during the war, making quick B-movies under his given name, Oscar Boetticher Jr, switching to the more familiar Budd with his first really personal feature, Bullfighter and the Lady (1952). Included in the set is the fifth movie attributed to him as director, Escape in the Fog (1945), an otherwise routine wartime espionage story into which is inserted an odd suggestion of something supernatural. The script was by Aubrey Wisberg, a prolific writer of low-budget movies who eventually teamed up with co-writer/co-producer Jack Pollexfen for a string of cheap genre movies which included E.A. Dupont’s wacky The Neanderthal Man (1953) and Edgar G. Ulmer’s no-budget gem The Man from Planet X (1951).

Escape in the Fog begins with Eileen Carr (Nina Foch) walking along a bridge in thick fog. Pausing at the railing, she’s accosted by a cop who assumes she’s about to jump. Assuring him that she’s okay, she continues to walk when a car abruptly stops nearby; there’s a fight, it looks as if someone is about to be killed and she screams, drawing the attention of the nearby cop. At which point Eileen wakes with a scream in her room in a San Francisco boarding house. Her neighbours have rushed to her room and one of them, Barry Malcolm (William Wright), turns out to be the man from her dream who was about to be murdered.

Both of them turn out to be recuperating from the stress of wartime service – she a former Navy nurse, he something which can’t be specified. They enjoy each other’s company for a day or two before he’s called away for more secret work. He’s an OSS operative who is now tasked with getting some crucial documents to the Chinese in Hong Kong in preparation for the final push against the Japanese. But enemy agents are on to him. Because of her dream, Eileen knows he’s in danger and having followed him to the house where his OSS handler Paul Devon (Otto Kruger) lives, she goes to the man to deliver an urgent warning. But Devon not surprisingly denies any knowledge of Barry.

Nonetheless, Eileen’s dream proves key to unravelling the enemy plot (which includes a recording device in Devon’s grandfather clock which has already exposed the whole secret mission) and eventually she winds up back on the bridge at night … in the fog … where she encounters the cop … and is prepared for the arrival of the car in which Barry has been kidnapped…

Breezily paced at a brief sixty-three minutes, Escape in the Fog is a fairly routine little movie with good guys and bad guys, a budding romance, a tense climax with Eileen and Barry tied in the backroom of the villain’s shop in Chinatown with the gas turned on – a sticky situation which Barry ingeniously manages to get them out of… Routine, that is, except for the strange dream device for which no explanation is ever provided. It’s the kind of thing which could only occur in a small B-movie being made without much scrutiny from the studio front office. Arbitrary and unexplained, it adds a note of interest which separates the film just slightly from the countless other similar B-movies being churned out at the time.

The Undercover Man (Joseph H. Lewis, 1949)

Like Budd Boetticher, Joseph H. Lewis began by toiling in studio B-movie units before forging a distinctive directorial persona with movies like Gun Crazy (1950) and The Big Combo (1955). The Undercover Man (1949), made immediately before Gun Crazy, belonged to the post-war genre of investigative procedurals which centred on federal agents (Treasury or FBI) who methodically and doggedly put together cases against organized crime figures. After the war, the chaos of the ’20s and ’30s when gangs very publicly vied for control of big cities had settled down and crime became much more efficiently organized as a business (this evolution is examined in detail in the Godfather movies). In response, the Feds became more organized too, pursuing big shots with tax laws and similar tools.

In The Undercover Man, the hero is a forensic accountant who plods his way through ledgers to find evidence of illegal activity and tax evasion. As played by Glenn Ford, Frank Warren is a deliberately dull bureaucrat who spends much of his time in a small airless room staring at columns of figures. Gradually piecing together connections and discrepancies, he seeks out small-time mob guys, digs up informers, and meets resistance and hostility from families who feel endangered by his attention. Rightly so, as the mob kills off those who might testify against them.

Warren has no direct contact with the shadowy figure known only as the Big Man, a stand-in for figures like Al Capone, dealing instead with mob lawyer Edward J. O’Rourke (Barry Kelley), who is adept at using the law to avoid criminal consequences – his client is “just a businessman” who is willing to do what needs to be done to keep the business going. Attempts to bribe Warren run into a brick wall of humourless rectitude, but threats against Warren’s patient wife Judith (Nina Foch again) shake the agent’s resolve.

It’s only when an immigrant woman and her granddaughter come to him with crucial evidence, determined to do what’s right because they didn’t come to the States to be oppressed by criminals the way they were back in Sicily, that Warren ploughs ahead despite the risks.

The movie offers a familiar story of decent people standing up to the violent criminals who oppress and exploit them, but it adds some interesting notes in the depiction of Warren and Judith. Early in the film, Warren is holed up in a small hotel room with his two partners, George Pappas (James Whitmore) and Stanley Weinberg (David Wolfe), who discreetly leave so Warren can spend a few intimate moments with Judith before she takes a train to her parents’ farm where she’ll stay for however long it takes for her husband to resolve the case. It’s a small domestic moment which humanizes the three men conducting a very unglamorous investigation. The overt violence perpetrated by the Big Man’s underlings, papered over by O’Rourke’s legal manoeuvres, is in the end effectively countered by these men’s decency and determination to do what’s right.

in Richard Quine’s Drive a Crooked Road (1954)

Drive a Crooked Road (Richard Quine, 1954)

Of the six films in the set, Richard Quine’s Drive a Crooked Road (1954) conforms most closely to the familiar tropes of noir. The protagonist is a guy bitter about what life has dealt him, yet he’s sustained by a dream; he meets and falls for a woman who (by movie standards) is out of his class and he learns too late that she has been using him duplicitously to help the guy she actually loves … and at the end, the stage is littered with dead bodies and, though he has survived, he’s learned some hard lessons that seem to confirm his original jaundiced view of the world.

Quine was one of those directors whose work was all over the place, so it’s hard to pin down a singular identity. A former actor and singer, he made a number of musicals and comedies (including favourites The Solid Gold Cadillac [1956] and Bell Book and Candle [1958]), but also tried his hand at noir with a couple of movies in 1954 – Pushover, with Fred McMurray and Kim Novak, and this one, Drive a Crooked Road. With a tight script by Blake Edwards and an excellent villain in Kevin McCarthy, the film has the fatalistic inevitability of noir. It also has Mickey Rooney as the bitter Eddie Shannon, a mechanic and amateur race driver who dreams of someday having enough money to own his own car and go to Europe to compete on the Formula One circuit.

Eddie’s bitterness is manifest in a large scar which runs vertically down his face from the centre of his hairline, around his right eye to his cheek. The scar, a memento of a bad crash during a race, forms a barrier between Eddie and the world, making him the cruel butt of coworkers who mock the hopelessness of any attraction he feels for a woman. And yet, when Barbara Mathews (Dianne Foster) shows up at the car dealership and asks for him personally to look at her car, his defences crumble. She shows up several times and he begins to think she really does like him.

This becomes a problem for Barbara because she actually sees him as a kind of sweet guy. Problem is, she’s luring Eddie into a trap for her criminal boyfriend Steve Norris (McCarthy), who has a plan for robbing a bank which can only work if he has a driver capable of covering a stretch of dangerous road in record time for the getaway. Eddie balks – he’s no criminal – and yet the payday would enable him to fulfill his dream. Taking the job for money is a pointed way of rejecting Barbara for her cruelty, even though by this point she’s against the plan because she doesn’t want to see him hurt.

The job takes place, the getaway is successful, but a series of betrayals inevitably lead to a bad ending, though Norris’ plan to kill Eddie backfires.

Ten years had passed since Rooney’s final Andy Hardy movie and the actor who had been the box office champion for a number of years had tried numerous ways to transition from adolesence to a more adult persona. He had continued to do musicals and comedies, but had also experimented with darker roles. That transition was embodied in Irving Pichel’s Quicksand (1950), in which Rooney played a young mechanic who “borrows” twenty bucks from his employer’s till to pay for a date, intending to replace it quickly. But circumstances rapidly get out of control and he finds himself sucked into a previously unimaginable world of noirish fate.

Drive a Crooked Road is something like a more mature extension of Quicksand, with Rooney working against his younger aw-shucks image. Eddie’s bitterness about the world makes him prickly and at times unsympathetic. Although the script is careful to indicate that the bitterness is a response to the way others have treated him, that treatment is partly due to the ugly scar bisecting his face, a scar which is the result of his own obsession with speed and his desire to prove himself better than other drivers on the race track. His own ego has created the obstacle and put him in a position which makes him vulnerable to Norris’ plan to exploit (and ultimately discard) him.

in Phil Karlson’s 5 Against the House (1955)

5 Against the House (Phil Karlson, 1955)

There are some similarities between Phil Karlson and Sam Fuller, both tough, male-oriented filmmakers with an interest in extreme experiences – manifest in westerns, war and crime films – and both prone to a bluntness which at times gives their work an air of crudity. All of that was apparent in the second Karlson movie I ever saw – Walking Tall (1973) – though not so much in the first – Ben (1972), the story of a lonely boy and his love for a killer rat. Somewhere around there I also saw his Matt Helm movies on television – The Silencers (1966) and The Wrecking Crew (1968) – which seemed among the worst Bond imitations, with Dean Martin not even phoning it in as he projected his contempt for the role from first frame to last.

It was much later that I came to appreciate Karlson at his best, particularly with Kansas City Confidential (1952) and The Phenix City Story (1955), the latter up there with Joseph Losey’s The Lawless and Cy Endfield’s Try and Get Me! (both 1950). Right before Phenix, Karlson made 5 Against the House (1955), based on a Jack Finney novel and considered by Columbia to be a showcase for the young Kim Novak whom they were grooming for stardom. The wisdom of that plan is debatable as Novak remains on the periphery of the narrative and the film’s emotional centre is actually the relationship between Al Mercer (Guy Madison) and Brick (Brian Keith), two Korean War buddies now enrolled in college. Al had saved Brick’s life, but a head wound has left him unstable, given to uncontrollable fits of rage.

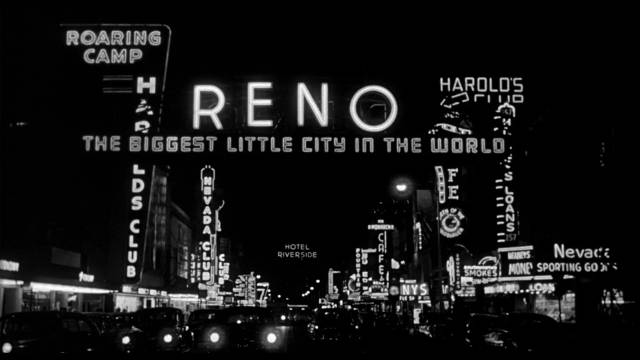

On their way back from a break, Al and Brick stop off in Reno with a couple of college friends, Roy (Alvy Moore) and Ronnie (Kerwin Mathews), and spend an hour gambling at (the real) Harold’s Club casino. Witnessing an attempted robbery and hearing the cops say there’s no way anyone could rob the casino, Ronnie begins to work out a supposedly infallible plan for a heist; just a theoretical heist of course, but he gradually persuades his friends that it can be done and proposes that they conduct an experiment and immediately return the money afterwards.

Al thinks it’s a dumb idea, but Brick sees it as a possible way out of a life he finds unbearable – he knows his brain damage is not going to improve, but there’s no way he’ll let them put him back in a VA psych ward. The money from the proposed robbery would enable him to run far away. Al reluctantly agrees to go along when Brick pulls a gun on the group, and the plan works, even with some unforeseen obstacles putting them in jeopardy. It falls apart after the fact when Brick becomes violent and takes off with the money, leading to a showdown in an amazing location which, as much as Harold’s Club, provided inspiration for the film – a robotic parking garage in which a complex lift system places vehicles on multi-tiered shelves. With the police closing in, it’s up to Al to talk Brick down and save his life.

So where is Kim Novak in all this testosterone-fuelled action? She’s Al’s girlfriend, a nightclub singer, who joins them on the trip to Reno and ends up taking a peripheral part in the heist. There’s some narrative tension derived from her presence, but her character seems inserted for reasons other than her being integral to the plot. The story is driven by two things: Ronnie’s intellectual curiosity, which sees the robbery as a puzzle to be solved, and the emotional bond which binds Al and Brick, rooted in their extreme experiences in the war and the post-traumatic stress that hangs over their post-war lives. In a sense (though naturally it’s not spelled out), the film’s love story is between the two men, Barbara inserted to deflect attention with an arbitrary and conventional “romance”.

Performances are good and the mechanics of the robbery convincingly developed – as in all good heist movies, these mechanics are carefully and clearly laid out for the audience. In fact, they were so convincing that Harold’s Club (which surprisingly allowed the production to shoot on the premises) changed its security procedures after the movie was made.

in Robert Aldrich/Vincent Sherman’s The Garment Jungle (1957)

The Garment Jungle (Robert Aldrich/Vincent Sherman, 1957)

The Garment Jungle (1957) has the most interesting backstory in the set. For a Hollywood movie in the ’50s it’s remarkably sympathetic to the idea of unions. Where in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) the dramatic hinge is organized crime infiltrating unions (a metaphor for communist infiltration of the movie business, retroactively justifying Kazan’s cooperation with the House Un-American Activities Committee), in The Garment Jungle organized crime is allied with business owners to crush unions – which of course want to unjustifiably steal the owners’ money and give it to workers who should just be grateful that someone has deigned to give them a job.

The business here is the garment trade in New York, where immigrants slave away in sweatshops, working long hours for very little pay. At the start of the film, businessman Walter Mitchell (Lee J. Cobb) argues with his partner Fred Kenner (Robert Ellenstein) about allowing their employees to organize – Mitchell hates the idea of giving up any of his profits while Kenner thinks it makes sense to share with the people who make those profits possible. Soon after the argument, Kenner dies in an elevator accident and Mitchell’s resistance to the union becomes absolute.

This is when Mitchell’s son Alan (Kerwin Mathews again) returns home after spending some time in Europe following his service in Korea. Alan is greeted warmly, but immediately angers his father by saying he doesn’t want to go into the family business. Yet he eventually does get drawn in from an oblique angle when he meets activist Tulio Renata (Robert Loggia) and his wife Theresa (Gia Scala). He admires Tulio’s passion and commitment and is attracted to Theresa; getting to know them, he comes to identify with the workers’ struggle and learns that his father uses gangster Artie Ravidge (Richard Boone) and his goons to suppress union organizing in the company.

Violence escalates and the conflict between Alan and his father intensifies until the latter is forced to face what he has become – for a long time he has avoided acknowledging what he’s really been paying Ravidge for, but when confronted with the fact that the mobster had both Kenner and Tulio killed, he has to accept that his own greed has made him a monster himself. He also discovers that Ravidge is the one with the real power in their relationship.

With Alan finally taking over the business, the union is allowed in and a more humane practice is finally established along the lines originally proposed by Kenner.

The film was almost complete when original director Robert Aldrich was unceremoniously removed. There had been conflict throughout the shoot between Aldrich and studio head Harry Cohn about the direction the film should take – with only a few days left on the schedule, when Aldrich was sick for a day, Vincent Sherman stepped in so production wasn’t interrupted. When Aldrich returned the next week, he discovered that he was no longer director. Sherman ended up re-shooting a lot of scenes and at this point no one really knows what is his and what is Aldrich’s. Aldrich himself gave many different accounts in ensuing years. The main points seem to be that he was mostly shooting on location in New York, while Sherman shot a lot of interiors on soundstages in Hollywood, undermining some of the original authenticity, and at Cohn’s insistence more emphasis was put on the “romance”, though nothing actually happens between Alan and Theresa.

Whatever the actual facts, The Garment Jungle remains a fairly strong drama with a leftist bent. From a dramatic point of view, as Cobb himself noted, Marshall is either a fool or a monster and either way it’s difficult to buy that he remains blind so long to what Ravidge has been doing in his name.

in Don Siegel’s The Lineup (1958)

The Lineup (Don Siegel, 1958)

Hollywood had a deep-seated antagonism towards television in the 1950s as the box siphoned off large sections of the audience which had previously flocked to theatres every week. In light of that competition, it was a rare and unlikely move to adapt a TV show for the big screen (why would anyone pay to see what they got for free every night in their own home?). Jack Webb had done it in 1954 with a feature version of the long-running Dragnet (1951-59), and Don Siegel made The Lineup (1958), based on another TV show which ran from 1954 to 1960 (following a successful four-year run on radio from 1950 to 1953). While Webb’s movie adhered closely to the TV formula, Siegel’s film headed in a different direction.

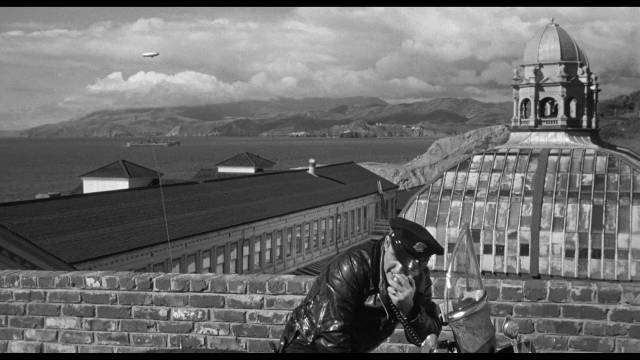

Stirling Silliphant’s script barely gives any attention to the San Francisco cops who every week solved some crime based on an actual case, focusing instead on an unusual pair of criminals. In this, the film looks ahead to the ’60s (and away from the television of the time, which would have been unlikely to dig so deeply into creepy psychopathology). The series’ cops remain virtual non-entities in the movie, their pursuit of a pair of killers and a drug smuggling ring limited to a few perfunctory scenes. Their presence seems most redundant during the eponymous lineup, shoehorned in to justify the title but carrying no narrative weight at all. Siegel himself felt it would have been better to sever ties with the series and simply make a stand-alone movie about the characters who really interested him.

That would be hired killer Dancer (Eli Wallach) and his effete handler Julian (Robert Keith) who have been called in by the man in charge of smuggling heroin from the Orient, known only as The Man (Vaughn Taylor). Dancer is cold-blooded and somewhat insecure about his lack of education; Julian coaches him in proper grammar and in return Dancer passes on the last words of his victims, which Julian collects for a hobby.

The movie begins with a bang. A man has just arrived back in San Francisco on a liner and a cabbie grabs his luggage and pulls away fast; the cab hits and kills a cop and then crashes. This leads to the discovery of heroin hidden inside a souvenir in the luggage and the police quickly realize that the tourist was an unwitting smuggler. To get the drugs through customs criminals plant them on ordinary travellers and then recover them once they’re back in the States. It’s Dancer and Julian’s job to visit each carrier and collect whatever object is concealing the drugs.

They’re on a tight schedule with a late afternoon appointment to deliver the drugs to The Man and as things don’t go smoothly, Dancer becomes more violent. The most intense set-piece involves a woman and her young daughter. The drugs were hidden inside an ornate doll, but now they’re gone – there’s a disturbingly perverse moment as Dancer pokes about under the doll’s dress in front of the young girl. It turns out that the girl had discovered the heroin during the voyage home and used it as face powder on the doll. This presents a serious problem for Dancer and Julian because if they come to the delivery short, they’ll be suspected of dipping into the goods.

So in a second big set-piece, instead of stashing the drugs and walking away, Dancer hangs around to try to explain to The Man what happened. This takes place in a museum full of kids and tourists. The meeting doesn’t go well. The Man, who arrives in a wheelchair, gives Dancer a very cold welcome – no one is supposed to see him and because Dancer has now seen him, “you’re dead”. He slaps Dancer across the face with the bag full of dope; enraged, Dancer grabs the wheelchair and dumps The Man over the balcony rail. In the ensuing panic, Dancer escapes, but the police have already spotted the car he and Julian have been travelling in. The climax is a high-speed chase which eventually ends on an unfinished freeway.

Siegel makes the most of the San Francisco locations, thirteen years before introducing Harry Callahan to the city, and obviously revels in the twisted relationship between Dancer and Julian. Although the supporting cast is good, the film belongs to Wallach and Keith, a pair of villains as distinctive as any seen as the hold of the Production Code was loosening. Even Variety said that too much time was spent on the police procedural element, a rather dull distraction from the real interest, which was definitely the flamboyant bad guys.

*

in Joseph H. Lewis’ The Undercover Man (1949)

As usual with Indicator, all the transfers are excellent. Each film gets a commentary (two for The Lineup), and there are archival interviews with Mickey Rooney, Kim Novak and Robert Loggia. Tony Rayns goes over the troubled history of The Garment Jungle, Martin Scorsese introduces Drive a Crooked Road and Christopher Nolan talks about noir. There’s a World War Two battle film edited by Budd Boetticher, a promo short with Rooney looking back on his early kids’ films, and a short by Joseph H. Lewis promoting the newly formed state of Israel. In addition, each film is accompanied by a Three Stooges short which roughly touches on the theme of the film it’s with.

Comments