Ousmane Sembène’s Mandabi (1968): Criterion Blu-ray review

When encountering work from a very different cultural perspective, I’m often not quite certain how to “read” what I’m seeing. With someone like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, for instance, it’s perhaps too easy to fall into an ethnographic perspective which ends up imposing a western frame on something which is actually a vital expression of a completely different perspective. In some ways, my response to the work of the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène is more complicated. His films emerge from the point of view of the colonized, while I was born into the dying days of a colonial empire.

Through his films and writings, Sembène was exploring the nature of identity from the other side of the colonial divide, while I was raised with a critical perspective on the violent history of European empires. The danger was always that, in compensation for a sense of guilt, there was a tendency to romanticize the oppressed and their resistance. But even that was an outside perspective; how could I really grasp the lived reality of those who for centuries had been shaped and defined by their oppressors?

I’ve only just now got around to seeing Sembène’s work. Before watching the new Criterion release of his second feature, Mandabi (1968), I decided to watch his first short film, Borom Sarret (1963), and his first feature, Black Girl (1966), to gain some perspective (I have the BFI Blu-ray edition). This proved very illuminating.

Borom Sarret (The Wagoner) recounts a day in the life of a poor man who scrapes a living by carrying people and goods through the streets of Dakar. He works hard, but many people fail to pay for his service and poverty grinds him down. Tempted by a more substantial fee, he agrees to take a man into modern Dakar, where carts like his are forbidden. When he’s stopped by a policeman, his fare slips away without paying and his cart is confiscated; he returns to his shantytown home with his weary horse and no money, facing an even harder existence than at the start of the day.

In Black Girl, a young woman who has been working as a nanny for a bourgeois French couple in Dakar, travels to France to continue her employment in Antibes. When she gets there, she finds herself virtually imprisoned in their highrise apartment, treated with condescension as an indentured servant. The position which had given her a certain status in Dakar becomes intolerable in France and she stubbornly begins to resist the oppressive treatment she receives; her employer becomes increasingly angry and intolerant, incapable of understanding the woman’s “ingratitude”, leading to a tragic conclusion. The shadow of slavery lies over the economic and social inequities exposed here between Africa and Europe.

Both these films were shot in stark black-and-white and have more than a touch of neorealism about them. With no indigenous tradition of African filmmaking to draw on, Sembène borrows the forms of European cinema to create his critique of the lingering effects of colonialism. The problem of defining an African identity in this context is further complicated by the necessity (dictated by a marketplace dominated by European money) of making both films in French, the imposed language of the former colonial masters which had been adopted as an official language in Senegal. While exploring the effects of neocolonialism on African lives, these films were themselves somewhat imprisoned by those lingering colonial forces.

For his second feature, Mandabi, Sembène adapted one of his own novellas. Again working with French resources, Sembène found a new constraint imposed on him – the film must be made in colour, something he was reluctant to do. However, this time the film was to be more determinedly African: it would be the first feature made in an indigenous African language, Wolof, the dominant language of Senegal. The use of this language and of colour give Mandabi (The Money Order) a very different flavour from the two bleak previous films. It has the air of a fable, which initially (for this viewer at least) risks seeming like an exotic travelogue. But as the simple narrative grows more complex, Sembène peels back more and more layers which expose not only the social and economic inequities of neocolonialism but also the devastating internalization of those forces in characters who have been left behind as the new post-colonial nation increasingly adopts the structures and attitudes of the former colonial powers.

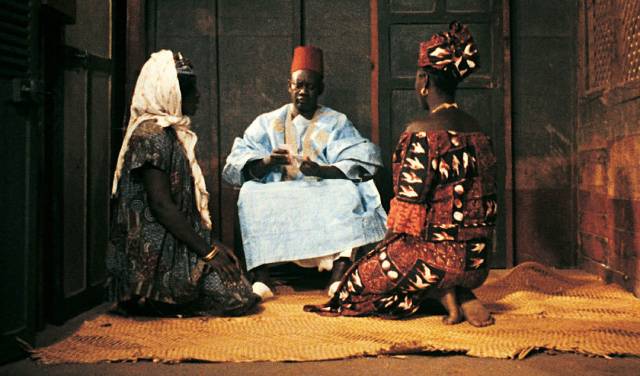

Ibrahim Dieng (Makhouredia Gueye) lives in a shantytown on the outskirts of Dakar. A rather pompous figure whose colourful clothes belie his poverty, he has two wives and seven children and the family lives in a state of perpetual debt. His sense of pride makes him bristle with indignation when his creditors demand payment. These creditors, like him, live on the fringes of a society which now has little use for them. These are people who have been left behind by a progress defined by neocolonialism. To deflect any possible admission of his own redundancy, Ibrahim makes a great display of his devout religion, despite not making any particular effort to adhere to its practices – he sleeps through the call to prayer, angrily blaming his wives for the oversight. His position as family patriarch is enforced with threats of violence, and yet it quickly becomes clear that his two wives are smarter than him and more skilful at juggling the economic demands which oppress the family.

One day when he is away from home the postman arrives with a letter from France; Ibrahim’s nephew, who works abroad as a street sweeper, has sent a money order for 25,000 francs. The wives immediately go to buy food for the family on credit in anticipation of cashing in on this windfall. When he returns, Ibrahim gorges on a large meal without questioning the source of this sudden bounty. It’s only after his post-prandial nap that he’s informed of the money order, by which time rumours have spread through the neighbourhood. Creditors and acquaintances begin to come around, trying to take advantage of Ibrahim’s luck … but first he has to cash the money order.

At the post office, he’s asked for official ID, but he has no papers. To make matters worse, he gets a man whose business is to read and write letters for the illiterate (played by Sembène himself) to read his nephew’s letter and discovers that most of the money is to be held for the nephew’s return, some given to his mother (Ibrahim’s sister), with only a few thousand for Ibrahim himself. The windfall instantly shrinks; he’s not even potentially as wealthy as he, his wives and neighbours had imagined.

But for now, there’s not even that more modest amount. He has to go in search of official papers. He goes to the local police station for an ID card, but it can’t be issued until he has a birth certificate and photographs. At city hall, he’s asked for his birthdate, but he only knows the year (and isn’t entirely certain of that). That’s insufficient. A middle class acquaintance who has a connection manages to straighten out this particular problem; Ibrahim is to return the next day with the photographs. But he has to borrow money to get them and after surveying a number of photographers’ shops, perhaps intimidated by the aura of established businesses which belong to another class, he pays a couple of shady characters in an alley, who take his money without actually providing the photos.

And so it goes, at every step, seemingly helpful people take advantage of him, his dignity becoming increasingly shredded and the prospect of actually obtaining the money more unlikely. As in the previous two films, the divide between rich and poor is also marked by a separation between traditional and modern, between indigenous culture and a bourgeoisie which has shaped itself in the image of the former colonial power. Ibrahim, with his inflated sense of himself, initially seems like a bit of a buffoon, but that self image has been formed in defence against marginalization; as events keep going against him, his defences prove flimsy and inadequate and satire edges towards tragedy. His lack of education and poor understanding of the society which has left him behind make him vulnerable to exploitation by people who have lost all sense of a shared community, people for whom greed and a lack of empathy have become the essence of social relations.

Sembène sees the damage done by colonialism and finally, turning from satire and a comedy of manners to a direct address to the audience, proposes the necessity of a radical rethinking of society rooted in the Marxist principles he absorbed in his years as a worker in France before he became a writer and, eventually, filmmaker. Active in unions as a dock worker in Marseilles and assembly-line worker in a car factory, his critique goes beyond neocolonialism to a fundamental need to reshape the society of both colonizers and colonized along more equitable lines.

*

The disk

Criterion’s 4K restoration from a 35mm interpositive gives the film a richly colourful look which initially conceals the darker undertones of the narrative and its themes. The contrast between this and Sembène’s more austere previous films couldn’t be more pronounced. Despite his reservations about using colour, the richer image and the use of Wolof give Mandabi greater depth and temper a sense of despair with the possibility of a more positive direction rooted in both the past and a transformed present.

The supplements

There are four extras on the disk, totalling 91 minutes, which focus on Sembène’s importance as “the father of African cinema” and, more broadly, as a writer and theorist of post-colonial politics. A lengthy introduction by film and African studies authority Aboubakar Sanogo (29:46) and a conversation between author and journalist Boubacar Boris Diop and feminist sociologist Marie Angelique Savane (19:25) situate Mandabi within Sembène’s political practice and the context of African literature and cinema. Praise Song (15:18) is a tribute to Sembène’s influence on a range of people – including musician Youssou N’Dour, author NgUgi wa Thiong’o, filmmakers Clarence Delgado and Manthia Diawara, and American political activist Angela Davis – comprised of unused interview clips from the feature-length 2015 documentary Sembène! by Jason Silverman and Samba Gadjigo. Also included is Sembène’s short film Tauw (1970, 26:47), which deals with the lives of unemployed youth in Dakar.

The booklet includes an essay by critic Tiana Reid and an interview with Sembene from 1969. A second booklet contains a translation of Sembène’s original 1966 novella The Money Order.

Comments