Winter viewing: Severin Films

Severin, like Vinegar Syndrome, offers its monthly releases in discounted bundles, often with the option of additional goodies like t-shirts, pins, reprints of photo comics of the movies, and figurines … and I’ve occasionally paid the extra for one of these deluxe limited editions because, well, I’m a sucker for “stuff”. This past Thanksgiving their Black Friday bundle included seven new Blu-rays plus an audio book of Richard Stanley reading Lovecraft’s novella The Color Out Of Space. Needless to say, I placed an order as soon as the sale started.

Like Vinegar Syndrome’s Drive-In Collection, Severin’s sub-label Intervision offers a couple of double-features, though in this case the movies are from the later direct-to-video years when the burgeoning home market demanded so much product that filmmakers were churning out ultra-low-budget movies which typically relied on genre hooks to get past all manner of creative limitations. The upside was that the free-for-all atmosphere encouraged the more adventurous to take chances and stretch their imaginative muscles. The four movies on these two disks are a mixed bag, but even the weakest would make entertaining party viewing.

Dream Stalker (Christopher Mills, 1991)/Death by Love (Alan Grant, 1990)

Dream Stalker (1991), uncredited on screen and packaging, but attributed by IMDb to sound and camera technician Christopher Mills, has Brittany (Valerie Williams) haunted by her dead biker boyfriend Ricky (Mark Dias) in a really confusing narrative which shifts between “reality” and nightmares so often that you seldom know what’s going on. Ricky becomes increasingly monstrous and makes Brittany’s life hell. On the same disk, Alan Grant’s Death by Love (1990) has sculptor Joel (Grant) plagued by a childhood acquaintance named Edgar (Frank McGill) who’s apparently a serial killer who has decided that Joel is the devil; which makes him kill anyone who gets close to the artist.

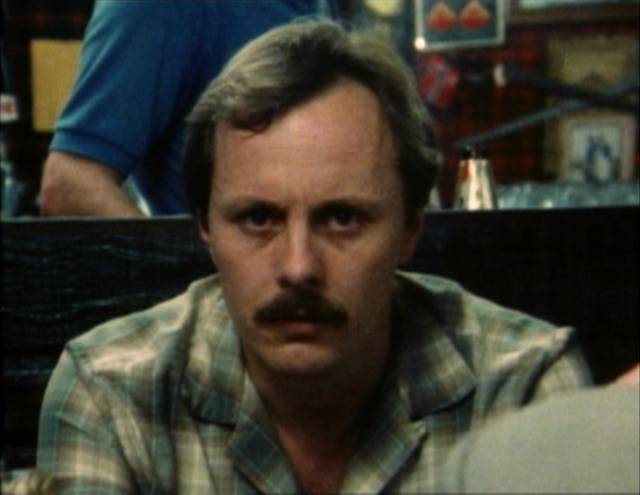

Murderlust (Donald M. Jones, 1985)

More interesting are a pair of movies directed by Donald M. Jones. You expect Murderlust (1985) to be sleazy sex-and-violence exploitation, but it turns out to be a surprisingly intelligent serial killer outing, with the sex and violence toned down in favour of a psychological character study of a guy named Steve Belmont (Eli Rich), who has a day job in a warehouse and spends his weekends as a Sunday School teacher and youth counsellor. His hobby, though, is picking up vulnerable women in his van and taking them out to the desert where he kills them and dumps their bodies in a ravine. The links between his religious authoritarianism and his murderous impulses are explored with more depth than you’d expect, making this one of the more interesting contributions to the overcrowded serial killer genre. (Several interview featurettes)

Project Nightmare (Donald M. Jones, 1987)

Although released in 1987, Jones’ Project Nightmare has an on-screen copyright date of 1979, indicating that it was his first feature. Undeniably less accomplished than the later movie, it’s considerably stranger. A couple of friends are fleeing something in the woods, eventually arriving at a remote house occupied by a woman who feeds them (and offers more than food and coffee), before sending them on their way with a bag lunch. They wander around, occasionally attacked by lights in the sky, before arriving back at their car. More wandering around, driving, finding a small plane in the desert, which one of them flies off in. The other finds an underground lab where someone’s doing experiments which seem to be distorting space and time… I’m not sure what’s really going on in this rather talky effort, but Jones gets points for trying. (Commentaries on both from producer James C. Lane)

Castle of the Creeping Flesh (Adrian Hoven, 1968)

Continuing with the Severin Blu-rays in chronological order, Castle of the Creeping Flesh (1968) was directed by actor-turned-producer and director Adrian Hoven two years before producing (and partially directing) Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil (1970). That film’s sadistic violence is already present here, but in a modern setting. A decadent party rife with lust (and culminating in a nasty sexual assault) leads a group of jaded bourgeoisie to the castle of the reclusive Graf Saxon (Howard Vernon), who tries to counter an ancient family curse with transplant surgery. His daughter having recently died, he allows the visitors to stay because he needs some spare parts. Titillating nudity is rather offset by lengthy and graphic depictions of actual open-heart surgery. The real draw here is Vernon at his ripest as the mad Count. (Interview and Q&A with Hoven’s widow and son, plus a locations featurette and alternate German title sequence)

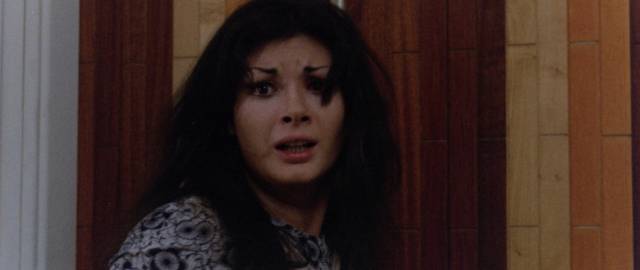

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (Sergio Martino, 1971)

Sergio Martino’s The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971), the first of five gialli in three years, did as much as Dario Argento’s movies to define the genre. It was also the first of three Martino gialli to star the distinctive Edwige Fenech, here the bored wife of a diplomat, who is haunted by memories of her sado-masochistic relationship with the vicious Jean (Ivan Rassimov) who returns to complicate her life as she begins an affair with George (George Hilton), the cousin of a friend. Blackmail, murder and plot twists ensue in stylish widescreen accompanied by Nora Orlandi’s atmospheric score. (Interviews with Martino, writer Ernesto Gastaldi, actors Hilton and Fenech, a commentary from Kat Ellinger, plus a CD of Orlandi’s score)

Shock Treatment (Alain Jessua, 1972)

Alain Jessua’s third feature, Shock Treatment (Traitement de choc, 1972) is a mix of horror and satire, somewhat reminiscent of Rod Hardy’s Thirst (1979). Approaching middle age and vaguely depressed, Helene Masson (Annie Girardot) checks into the Devilers Clinic which has been recommended to her by some well-off friends. It’s expensive, but she’s been assured the exclusive treatment will really improve the quality of her life. She meets an old friend who has been there a number of times, but is now stressing because he can no longer afford to pay the high fees; when he turns up dead at the bottom of a cliff, the police rule it suicide, but Helene is already having doubts. There’s a creepy cult vibe about the clinic and its charismatic founder Dr. Devilers (Alain Delon), who is quite happy to sleep with his female clients, including Helene. Becoming increasingly aware of the economic and social divide separating the clients from the young Portuguese guest workers who maintain the clinic, Helene starts investigating things behind the scenes, eventually uncovering the horrific truth about the Devilers revitalizing technique. Jessua develops the narrative with slow inexorability, aided by fine performances and Jacques Robin’s excellent cinematography. (Interviews with Jessua, co-writer of the score Rene Koering and Cinematheque Francaise curator Bernard Payen, partial commentary by Koering, plus a soundtrack CD)

The Astrologer (James Glickenhaus, 1975)

Best known for a string of violent ’80s action movies, James Glickenhaus directed his first feature in his early twenties, straight out of film school. Adapted from a novel by John Cameron, The Astrologer (1975) is a messy mix of New Age hocus-pocus, religious claptrap and apocalyptic horror. A secret government agency uses astrology to manipulate events and guide the human race towards the next stage of evolution; meanwhile a cult leader in India is doing something similar for nefarious purposes. Racing against time, everyone is looking for a woman destined to give virgin birth to the avatar on whom everything hinges. Glickenhaus was still figuring things out and the movie is very lumpy and over-burdened with dialogue. An interesting curiosity, very different from his subsequent work. (Interviews with Glickenhaus, actor Monica Tidwell and a couple of crew members, plus a locations featurette)

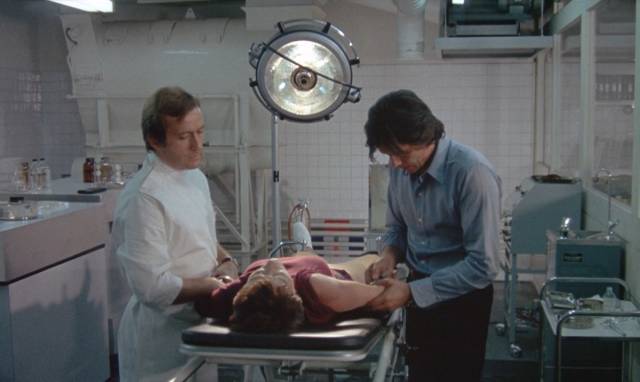

Patrick Still Lives (Mario Landi, 1980)

After making the extremely sleazy Giallo a Venezia (1979), Mario Landi piggybacked on the success of Richard Franklin’s Australian supernatural thriller Patrick (1978) with the blatantly titled Patrick Still Lives (1980). The set up is similar – a young guy named Patrick (Gianni Dei) ends up in a coma after an accident and reaches out psychokinetically to kill those responsible for his condition. He’s kept in his father’s country house clinic, with Dad doing some experiments on him and other comatose patients. Everyone involved ends up on the premises and gruesome deaths ensue – although the movie repeatedly diverts into fairly explicit sex scenes. The latter get more attention than the ostensible plot and overall it’s a bit of a slog. (Brief interview with star Dei)

Killer Crocodile (Fabrizio De Angelis, 1989)

When it comes to giant killer critters, it doesn’t really matter how many cliches are trotted out. For some reason, we love to see people getting eaten. By 1989, the momentum provided by the success of Jaws (1975) might have faded, but director Fabrizio De Angelis hits most of the right notes with Killer Crocodile. A group of young environmentalists head into a tropical swamp to track down the source of rising radiation levels (a corporation is dumping toxic waste in violation of the law), a task which involves stripping off to skimpy swimwear and diving into the polluted water. The sludge has naturally caused mutations, one of which is a really, really big and angry crocodile. The animatronic creature is more impressive than expected and the attack sequences are very well handled.

Killer Crocodile 2 (Giannetto De Rossi, 1990)

The sequel, imaginatively titled Killer Crocodile 2 (1990), essentially repeats the formula, although tree-hugging hero Kevin (Richard Anthony Crenna) from the first film comes back wanting to get all medieval on mutant crocodile ass. Directed this time by Giannetto De Rossi, the make-up and effects master responsible the creature effects in the first movie, it doesn’t have much plot, but there’s a big, impressive set-piece in which the beast destroys the building our hero and various others are hanging out in. Nothing original in either movie, but together they provide a fine evening of animal mayhem. Added bonus, both were scored by the great Riz Ortolani. (Interviews with De Rossi, actors Crenna and Pietro Genuardi, and cinematographer Federico Del Zoppo)

The Black Cat (Luigi Cozzi, 1990)

Starting out as a script by Daria Nicolodi for the third film in Dario Argento’s Three Mothers trilogy, The Black Cat (1990) underwent major changes after landing in the hands of Luigi Cozzi, prompting Nicolodi to back out both as writer and star. In the process it became pretty meta (and a typical Cozzi mess). Filmmaker Marc Ravenna (Urbano Barberini) is preparing to make the sequel to Suspiria and Inferno; his wife, actress Anne Ravenna (Florence Guerin) is set to star, though her best friend Nora (Caroline Munro) also covets the role of the Third Mother, a witch named Levana. Unfortunately, she’s not a figment of the writer’s imagination and one evening bursts out of a mirror and vomits all over Anne. She doesn’t want any part of the movie and people around the production begin to die in gruesome ways. Colourful and gory if not coherent, this is one of Cozzi’s better movies. (Interview with Cozzi and Munro)

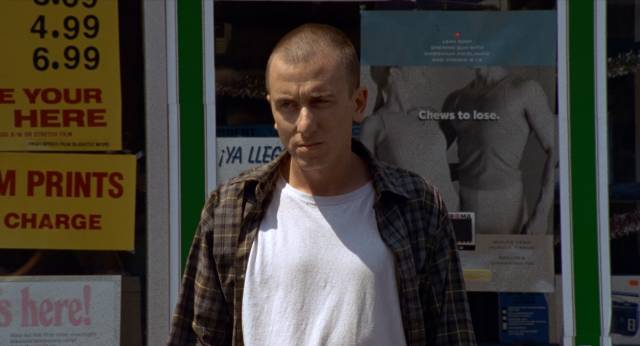

No Way Home (Buddy Giovinazzo, 1996)

Buddy Giovinazzo’s first feature was the grim and gritty post-traumatic shock masterpiece Combat Shock (1984). Since then, he seems to have made only four more features, plus a lot of television episodes, mostly in Germany. Of the features, the only other one I’d seen until now was Life is Hot in Cracktown (2009), a multi-character story about people whose lives intersect in a drug-plagued inner city. His second feature, made twelve years after Combat Shock, was No Way Home (1996), which takes what could be a bunch of cliches and breathes potent dramatic life into them. Joey (Tim Roth), kind of slow and generally unassertive, gets out of prison after serving six years for killing someone during a robbery; he returns to the family home occupied by his brother Tommy (James Russo) and sister-in-law Lorraine (Deborah Kara Unger). He’s at risk because Tommy is dealing drugs and owes money to dealers, which could easily get Joey sent back to prison. The three-way relationship is developed with subtlety and emotional depth, leading to an explosive conclusion which exposes painful truths about the brothers’ troubled history. (Director commentary, multiple crew interviews, early short film by Giovinazzo, and a soundtrack CD)

The Attic Expeditions (Jeremy Kasten, 2001)

Movies in which reality is uncertain are tricky, particularly if the filmmaker doesn’t provide something that feels like firm ground from which to launch the uncertainty. That’s the case with Jeremy Kasten’s first feature, The Attic Expeditions (2001). It takes place inside a psychiatric institution (maybe) which never feels quite real, so when we slip in and out of what may be the dreams, memories or delusions of Trevor Blackburn (Andras Jones) it tends to feel weightless. Incarcerated for apparently killing his girlfriend during a Black Magic ritual, Trevor is being subjected to experiments by Dr. Ek (Jeffrey Combs), who it gradually becomes clear is digging for esoteric occult secrets. Maybe. Ek explains his techniques to newly arrived Dr. Coffee (Ted Raimi), but we’re not much the wiser. Combs and Raimi make a good comic duo, while Wendy Robie (Twin Peaks’ Nadine) as another doctor and Seth Green as a hyperactive patient push things further towards comedy. But Jones isn’t able to give a lot of depth to the tormented protagonist. (Several cast and crew featurettes, plus a soundtrack CD)

Family Portraits: A Trilogy of America (Douglas Buck, 2003)

Family Portraits: A Trilogy of America (2003) is actually three short films made between 1996 and 2003 strung together as a feature. Harrowing suburban horror, seen together the films highlight the increasing skill of writer-director Douglas Buck. Cutting Moments (1996) is the most overtly provocative with some of the most painful scenes you’re likely to see. It’s also the most oblique of the three, requiring the audience to intuit what’s happening. Dad Patrick (Gary Betsworth) has apparently been abusing his young son, something Mom Sarah (Nica Ray) now knows. As they wait for the authorities to show up and separate the family, she goes to increasingly extreme measures to regain Patrick’s erotic attention, resulting in some appalling self-mutilation. Betsworth again plays a problem Dad in Home (1998), crushed by a tedious career and haunted by his own childhood in which he was abused; he eventually visits that abuse on his own wife and child, leading to another bloody climax.

The third film, Prologue (2003), is both less overtly violent (at least, less graphic) and far more disturbing, aiming not for explicit shocks but rather a lingering sense of emotional pain and outright despair. A young woman is brought home after a year in hospital, where she’s been undergoing extensive rehabilitation after being brutally raped; during the attack her back was broken, leaving her paraplegic, and both hands were cut off. She has no memory of what happened and is struggling to adjust. Meanwhile, outside of town a retired postal worker who’s something of an artist lives with his wife. The connection between these characters gradually emerges as the young woman’s memory starts to return. She wants to know why she was attacked and confronting the retired man, while it provides no answers or satisfaction, brings to the surface a history of appalling acts which his wife now has to deal with. Horror permeates the film, but each character is treated with empathy, even the monstrous serial killer. The first two shorts aim to shock, but Prologue is a mature work which has a far deeper and more lasting impact.

The films can be watched separately or as assembled for the theatrical feature release, the chief difference being the separate end credits, particularly on Home where the credits are intercut with additional images which extend the narrative. There are commentaries on the individual shorts, plus two commentaries on the feature. There are also 48 minutes of archival cast and crew interviews for Cutting Moments, three episodes of a podcast with Buck totalling more than two hours, a 16-minute student film by Buck, a deleted scene and a short making-of for Prologue.

Plague Town (David Gregory, 2008)

In addition to being one of the founders of Severin and creating hundreds of special features for numerous releases, David Gregory has made some exceptional documentaries about filmmakers – in particular his films about Richard Stanley and The Island of Dr. Moreau and the life and death of Al Adamson – but as far as I can tell, he’s only directed one dramatic feature. I saw Plague Town (2008) once on Dark Sky’s DVD, and it didn’t leave much of an impression, but I quite enjoyed it this time around. Not terribly original, but it generates a lot of atmosphere and has some effective imagery. An American family on vacation searching for roots in rural Ireland runs afoul of a village cursed with a genetic defect which results in not just deformed children but a nasty cult-like mentality which doesn’t bode well for the tourists. (In addition to porting over Dark Sky’s extras – a commentary and a couple of featurettes – there are two short films by Gregory and a long-form making-of by Howard Berger)

of The Theatre Bizarre (2011)

The Theatre Bizarre (Various, 2011)

The Theatre Bizarre (2011) was an enthusiastic attempt to recapture the heyday of horror anthologies. However, while the movies of Amicus and its imitators were generally written by a single writer and directed by a single director, this one offered a variety of filmmakers a chance to make independent films with no restrictions beyond keeping within a small budget. Naturally this precludes a consistent tone, but it keeps things interesting. The directors are Douglas Buck, Buddy Giovinazzo, David Gregory, Karim Hussain, Jeremy Kasten, Tom Savini and Richard Stanley and the individual films range from classical horror to gross out comedy to character pieces laced with violence. This film returned Stanley to drama for the first time since the collapse of Dr. Moreau in the mid-’90s; his segment, Mother of Toads, opens the program with a touch of Lovecraftian horror (adapted from a Clark Ashton Smith story). This is followed by Buddy Giovinazzo’s story of obsessive romantic fixation and murder in a Berlin apartment.

In Tom Savini’s segment an adulterous man has nightmares involving being castrated by his wife. That is followed by the quietest episode in which Douglas Buck deals with a young girl coming to terms with death. The tone abruptly shifts in what is certainly the most unsettling segment, directed by Karim Hussain, who also shot Stanley’s and Buck’s films; a woman has discovered that if she extracts the fluid from a person’s eye at the moment of death and injects it into her own eye she can experience the events of her victim’s life – she justifies this by killing society’s discards and then writing their lives in notebooks, convincing herself that she’s some kind of feminist crusader giving voice to those who’ve been silenced. Really hard to watch if you’re sensitive to eye trauma! In some ways, David Gregory’s episode is just as hard to watch (at least for me) as it involves really gross and messy eating by gluttony fetishists prone to vomiting on each other – the main course at the feast is one of the guests.

It fell to Jeremy Kasten to construct the frame which holds these pieces together and, perhaps unusual for this genre, his contribution is one of the highlights. A young woman working in an office glances from the window to see an old theatre across the street; attracted, she heads over and takes a seat. There are very few people there and the stage is littered with props and rubbish. The host is an automaton played with creepy humour by Udo Kier and he summons up through pantomime other automata who reflect the characters in the individual stories and their fates. As the show progresses, he becomes more lifelike as the woman watching gradually becomes an automaton herself, finally brought on stage to become yet another part of the show.

The disk includes new and archival commentaries, featurettes on individual episodes, an interview with composer Simon Boswell, an extended cut of Mother of Toads and a new feature-length documentary about the making of the film and its abortive distribution. There’s also a soundtrack CD.

Tales of the Uncanny (David Gregory & Kier-la Janisse, 2020)

As a kind of piece de resistance, the Black Friday bundle included a new feature-length documentary by Gregory and writer Kier-la Janisse about the history of anthology films. Made during the Covid lockdown, Tales of the Uncanny (2020) includes interviews with almost two-dozen filmmakers, writers and critics, mostly conducted over Zoom, giving it a fairly informal, home-made feel. While tracing the history of the anthology form, it’s primarily an opportunity for these people to share their own memories of seeing these movies and offering up their favourite stories. There’s more than a touch of nostalgia, reminding us of how our viewing is enhanced by sharing our experiences with others.

Along with the documentary, the Blu-ray contains two complete anthologies – a German silent from 1919 called Uncanny Tales, believed to be the first, containing five stories including adaptations of Poe and Robert Louis Stevenson; and a French feature from 1949 called Unusual Tales, directed by Jean Faurez, which again adapts Poe, plus this time Thomas De Quincey. The limited edition also includes another Blu-ray with a 1959 Argentinian adaptation of two Poe stories called Master of Horror, directed by Enrique Carreras. As with the Family Portraits and Theatre Bizarre releases, you definitely get more than your money’s worth!

Comments