Edmund Goulding’s Nightmare Alley (1947):

Criterion Blu-ray review

Movie stars held a paradoxical position at the height of the studio era. Idolized by fans who eagerly read accounts of their glamorous lives, those lives and careers were tightly controlled by the studio heads, who managed their stars’ image by carefully choosing the roles they would play. And yet the more popular a star became, the more leverage he or she would have … within limits. A refusal to take an assigned role would result in penalties, but the bosses might indulge a star’s desire to make a pet project, even if it didn’t promise big profits. The system, in order to remain commercially successful, needed to maintain some balance of power between the businessmen and the popular public faces of the studios.

During the 1940s, one of the most popular faces belonged to Tyrone Power, a big money-maker for 20th Century Fox, which carefully cultivated his matinee idol looks by casting him in heroic, romantic parts, frequently in swashbuckling costume movies. Power grew dissatisfied with the limitations this imposed on him and sought to stretch as an actor. He managed to persuade the studio to finance an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge in 1946, the story of a man who embarks on a years-long spiritual quest, but the role maintained Power’s romantic image. When the movie proved successful, the actor pushed harder by proposing an adaptation of a recent novel by William Lindsay Gresham, the story of a very different, much less wholesome character.

Nightmare Alley, published in 1946, was the sordid tale of a carny who cons his way up through society, only to fall back to the grim bottom of life in a sideshow. This was hardly the image Fox wanted of their star, and production head Darryl F. Zanuck was reluctant to okay the project. But he was also reluctant to alienate his big money-maker, so he eventually agreed – but did all he could to mitigate anticipated damage, not to mention possible conflict with the Hays Office. Given the nature of the material – the sordid setting, the protagonist’s criminality, the alcoholism and sexuality, the hints of occultism and the cynical view of religion – that was a genuine concern.

Although the novel had been well-reviewed, the subject matter seemed more appropriate to a B-movie, rather than a big budget A-picture. Often classed as film noir, Nightmare Alley is at least as much Gothic horror. It’s interesting to imagine a version akin to the psychological horror movies made for Fox a couple of years earlier by John Brahm, The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945), both starring Laird Cregar. But rather than going in that direction, Zanuck hoped to soften the material by hiring writer Jules Furthman (Howard Hawks’s Only Angels Have Wings [1939], To Have and Have Not [1944], The Big Sleep [1946]; Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco [1930], Shanghai Express and Blonde Venus [both 1932]) to adapt and Edmund Goulding to direct.

Goulding seemed like an ill fit for the project. Well-known as a woman’s director, he had brought MGM a Best Picture Oscar for Grand Hotel (1932), starring Greta Garbo, and had helmed a number of Bette Davis’s big pictures in the ’30s. He had also made The Razor’s Edge the previous year, garnering multiple Oscar nominations and one win, so Zanuck had reason to believe he could bring some class to this problematic new production. In this, Goulding was aided by cinematographer Lee Garmes, himself an Oscar-winner and former collaborator with von Sternberg. Despite the grimy, downscale setting of much of the film, Garmes gives it a mixture of realism and hallucinatory fantasy – the carnival is frequently seen at night in a hazy mist, while a fake encounter with a ghost late in the story takes place in an almost surreal grove.

But even if these efforts do strip away some of the grim edges of Gresham’s novel, the central darkness remains – and perhaps is paradoxically the more powerful for the attempts to disguise the ugliness with A-picture class. Even the most obvious attempt to mitigate what we see – a tacked on “happy ending” – can’t disguise the essential horror. The result was one of the darkest movies ever made by a major studio, a genuine nightmare of existential horror, which Zanuck was unwilling to back, giving it little promotion and all but guaranteeing its box office failure. After a limited release, Nightmare Alley pretty much vanished, living on as one of those mythic, little-seen movies which couldn’t possibly live up to its dark reputation. Hard to see, it finally turned up on DVD in 2005, and proved to be fully deserving of that reputation, just as Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) had been when it re-emerged after decades in the shadows.

*

Nightmare Alley (1947) is the story of Stanton Carlisle (Tyrone Power), a handsome man with a troubled past (an orphanage, abuse, a cynical adoption of religion to deflect his abusers) who has taken work in a carnival sideshow. He loves the life, the feeling of being a part of a community separate from and, in his view, superior to “normal” society. When we first see him, he’s hovering around the edge of a crowd staring in fascinated horror at the “geek”, whom we don’t see, though we hear the barker’s spiel and the panicked squawking of the chicken being tossed to the freak who, we understand, will bite off the head for the “entertainment” of the rubes. Stan wonders how anyone can sink so low.

He helps out with the performance of Zeena (Joan Blondell), who has a fake psychic act. Zeena and her husband Pete (Ian Keith) used to be a high-class act, but things went bad and Pete is now a serious alcoholic. Zeena feels responsibility for him, even though he’s dragged her down with him. Stan tries to get her to teach him the verbal code they used to use to fool their audience into thinking she had real powers, but Pete is fiercely possessive of the only thing he has left of value. One night, Stan tries to ingratiate himself by supplying Pete with booze behind Zeena’s back, but by accident he gives Pete a bottle of raw wood alcohol rather than moonshine … well, maybe it’s an accident, but the end result is that Pete dies, leaving an opening for Stan to revitalize Zeena’s act.

He’s a natural and their success gives him ideas about leaving the sideshow and moving up to a classy nightclub act like the one she once had with Pete. When things don’t work out, he persuades the younger, prettier Molly (Coleen Gray) to join him and the pair quickly become a big success, impressing rich society women with Stan’s apparent access to their deepest secrets. He plays the part to the hilt and even manages to win over skeptical men who try to expose him as a phoney. Stan quickly moves from answering harmless questions written on hidden pieces if paper to channelling dead loved ones, though Molly becomes uneasy about the direction he’s taking.

But by then he’s met Lilith Ritter (Helen Walker), a psychotherapist who caters to the same society women Stan has his sights on. As much a con artist as he is, once she sees how skilled he is, she joins him in a scheme to fleece her rich clients by feeding him information she gains during therapy sessions, increasing the convincing illusion that he has genuine psychic powers. Well on the way to making big money, Stan’s ambitious plans – he intends to build his own church to add weight to his claims and bring in more rich clients – are abruptly derailed when Molly’s conscience gets the better of her and she refuses to go through with her performance as the ghost of a rich man’s lost love.

Exposed, Stan realizes it’s time to cut and run, only to discover that he’s been cheated by Lilith, who not only keeps the money they’ve made so far but sets him up to be arrested and perhaps committed for psychiatric care. On the run, he drinks more and more and eventually, coming full circle, tries to get hired on as a sideshow psychic. But he’s in such poor shape that the show boss will offer him only the role of geek… Back at the start, Stan pondered how on earth anyone could sink so low. Having risen high and plunged really low himself, he now knows the answer. As he says to the boss, “I was born for it.”

From a Production Code standpoint, Stan has now been punished for his crimes and it’s time for redemption. Screaming with the DTs, he’s chased around the dark sideshow grounds and finally recognized by Molly who calms him and holds onto him. But this is a terribly unconvincing “happy ending”. At best, Stan and Molly may linger on like a reprise of Zeena and Pete, a sad nurturing wife trying to keep her alcoholic husband from terminal despair. But not only does the movie fail to restore some kind of balance and normalcy to Stan’s existence, it does nothing to address Lilith’s moral failings and criminal actions; she escapes completely unscathed and in possession of the money she and Stan conned from their victims, almost as if, distracted by the intensity of Stan’s fall, everyone involved forgot about her. It’s remarkable that Nightmare Alley made it to completion and managed to get released at all.

But the behaviour and fates of Stan and Lilith are not the only things that test the limits of the Production Code. While the details are elided, it’s quite clear that Stan and Molly are involved sexually – why else would the other show people force him to marry her? And although Zeena’s psychic act is shown clearly to be phoney, she also reads the Tarot and believes implicitly in the cards’ predictive power, a belief which the movie seems to endorse as her warnings eventually prove accurate; such an endorsement of an occult practice goes against the Code. And to make things more problematic, religion appears to be something which makes adherents gullible and ripe for exploitation by con-men like Stan, a weakness rooted in irrational beliefs. Psychoanalysis, something very popular in the ’40s and treated with fascination by Hollywood, is also presented as a kind of con, with Lilith using her practice to manipulate and exploit the wealthy.

The film continually upends the status quo which the Code was designed to support, and perhaps in Goulding’s conventional hands all this is more subversive than it would have been under a more openly confrontational filmmaker. He applies a classical studio style to material more suited to the expressionist exaggerations of noir, an approach which naturalizes transgressions which in a more obviously exploitative B-movie would have offended society’s moral guardians.

*

Tyrone Power, who ranked Nightmare Alley’s Stanton Carlisle as his favourite among the many roles he played, was never better. With his good looks and cocky charm, he begins as an appealing character with the audience on his side. It’s only natural that he’s interested in learning more about the various scams practiced by carnival folk and he obviously has a knack which he’s eager to build on. His appeal draws others to him, Zeena with a kind of maternal instinct, Molly with a naive romanticism. Pete isn’t so easily swayed, though he’s grateful when Stan offers him a drink (against Zeena’s wishes). Though it isn’t clear whether the switching of wood alcohol for moonshine is a genuine mistake, there’s no doubt that with Pete out of the way Stan’s career takes a big leap forward. As he starts up the ladder from sideshow to nightclubs to criminal schemes, his charm becomes more hollow, a performance designed to take advantage of others and conceal a lifelong insecurity which drives him to take dangerous chances instead of merely settling for a more manageable level of success.

After he falls from his peak, charm disappears into bitterness and cynicism and by the time he makes his way back to the carnival, he’s a brittle shell, life a gesture without hope, but nonetheless sufficiently self-aware to realize that he has finally arrived at a place he knew deep-down he was destined to be – his fascination with the geek in the opening sequence lay in an as-yet unacknowledged awareness that this pathetic, lost creature might so easily be himself.

Complementing Power’s performance are the three women who shape his story – a tribute not only to the actresses’ distinctive talents but also to Goulding’s notable ability with shaping female characters. Stan starts on his way with the nurturing support of Zeena, played with a mixture of strength and vulnerability by Joan Blondell, who was transitioning from the smart, brassy women she played in the ’30s into middle age; in Zeena the maternal element retains an erotic charge and Stan takes advantage of this to get what he wants from her.

Coleen Gray was at the start of her career when she played Molly, immediately after appearing opposite Victor Mature in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947). Young, bright and openly romantic, she’s swept away by Stan’s obvious charm, becoming a beguiling collaborator in the psychic act which brings him to the attention of wealthy socialites. But as his plans shift from showbiz to conning people with news – and eventually visions – of their dead loved ones, her own innocence and sense of what’s right and wrong make her see him for what he has become (and maybe always was). And yet she never stops loving him and comes back into his life just as he hits rock bottom, promising to pull him back from the abyss.

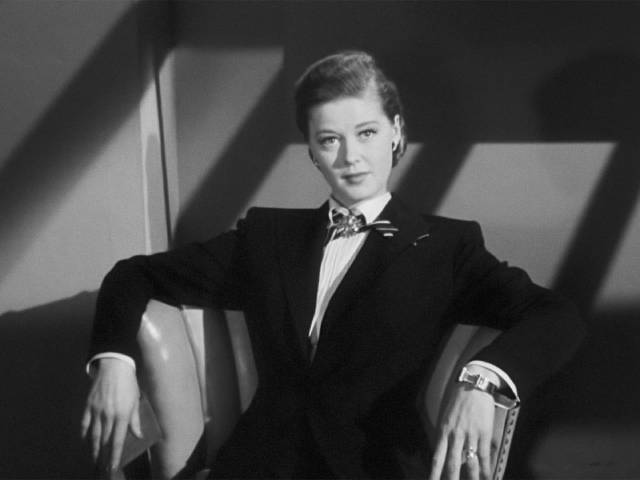

While these two are loving and supportive, Helen Walker’s Lilith Ritter is as chilling as any femme fatale in the darkest of film noirs, a woman as devoid of conscience as Stan is himself. But while his ambition is rooted in deep insecurities going back to a damaged childhood, she’s a monster of self-assured confidence, a woman without doubts or fears who exposes him as an amateur and, in their final scene together, dismantles him without breaking a sweat; her training allows her to see and understand his every weakness and she uses that knowledge to strip away all the protective mechanisms he has spent a lifetime constructing. It’s because of her that his fall is so swift and decisive, because of what she has laid bare that he is ready at last to take his place as the geek.

While these four performances are central to the film, players in smaller supporting roles are equally strong, particularly Ian Keith as the tragic Pete, Mike Mazurki as the strongman Bruno who is protective of Molly and distrusts Stan, and Taylor Holmes as a skeptic who tries to expose Stan and is instead sucked in by his con.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray presents another of their excellent 4K restorations of an older film, with a rich, atmospheric image and clear sound. Along with Dorothy Arzner’s Merrily We Go to Hell and Frank Borzage’s History is Made at Night, Nightmare Alley sets the standard for new presentations of classic Hollywood movies.

The supplements

The Blu-ray includes the commentary track originally recorded for the Fox DVD back in 2005, with noir experts James Ursini and Alain Silver filling in the production background in detail. There’s a brief archival audio recording from 1971 of director Henry King talking about Tyrone Power, with whom he made eleven movies (9:36), plus an interview with Coleen Gray about her work on the movie, recorded in 2007 (12:41).

New featurettes created for thus edition are an interview with critic Imogen Sara Smith (31:52), who speaks about the novel, Power’s campaign to get the film made, Zanuck’s misgivings, and the subsequent fate of the movie; and an interview with sideshow historian Todd Robbins (19:17), which fills in the context for Gresham’s novel and the evolution and gradual disappearance of sideshows as social attitudes and tastes in entertainment changed over the second half of the 20th Century.

There’s a trailer (2:30), and the booklet essay is by critic Kim Morgan.

Unusual for Criterion, there’s one other extra – a set of six Major Arcana Tarot cards highlighting the main characters.

Comments