Euro Pulp

I just can’t stop myself. There’s something about European genre movies that keeps me coming back. Is it the combination of style and often aggressively offensive content? The determination to attract an audience with transgressive themes and material designed to offend socially conservative sensibilities? Sometimes these movies are uncomfortably nasty, sometimes the nastiness spills over into subversive comedy. That sense of discomfort, of touching on the unacceptable, has appealed to me for as long as I can remember and yet to some degree has remained unexamined; perhaps it’s nothing more than a sign that I’ve remained immature, never having grown out of a kid’s love of grossing out his elders. Maybe it’s just the cinematic equivalent of eating a worm in the school playground and basking in the “yuck! That’s gross!” response of the other kids. Deep down, maybe there’s a sense of satisfaction, even pride, in being able to keep watching when so many others are likely to turn away.

*

Manhattan Baby & Murder-Rock: Dancing Death

(Lucio Fulci, 1982/1984)

Lucio Fulci was a master of the gross, presenting audiences with graphic, in-your-face gore – to a degree where in some of his best work more subtle elements may be obscured, as in a film like Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), which uses giallo tropes to explore the repressive social and religious pathologies of rural Italy. Still best known for his graphic horror movies from the late-’70s to mid-’80s, he worked in wide range of genres from the ’50s to the mid-’90s. As prolific as he was, with two or three features a year in the ’80s, it’s not surprising that even in that period when he made a string of genre masterpieces he also directed a number of minor movies.

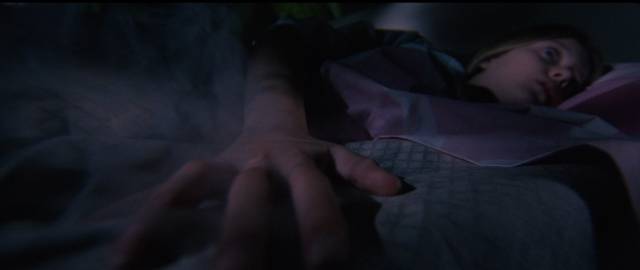

Manhattan Baby (1982) is pretty subdued for a Fulci feature, particularly considering that he made it immediately after New York Ripper (1982), his most extreme and disturbing giallo. Drawing some elements from The Exorcist (1973) – an opening set at an archaeological dig in the Middle East, a young girl possessed by an evil spirit – it’s actually more like an uncredited remake of Mike Newell’s dull The Awakening (1980), based on Bram Stoker’s 1903 novel The Jewel of the Seven Stars, itself the main source for Mummy movies.

Although nicely shot by Guglielmo Mancori in Egypt, New York and at studios in Rome, with an obsessive focus on characters’ eyes (Fulci had a fondness for eyes and gruesome eye trauma), the director can’t seem to pump much energy into a ragged, unfocused story involving an ancient amulet which provides access to other-dimensional doorways to ancient Egypt. Both Fulci and co-writer Dardano Sacchetti disowned the movie, citing producer Fabrizio De Angelis’s decision to cut the budget in half at the start of production. (By an odd coincidence, Newell more or less disowned The Awakening after it was re-cut without his input.)

Generally held in low regard by even ardent Fulci fans, the movie looks gorgeous on Blue Underground’s three-disk limited edition Blu-ray (dual-format, with a CD of the soundtrack). Perhaps it would rank more highly if the budget had permitted filming the full script, but it’s still quite watchable even if it lacks Fulci’s usual excesses.

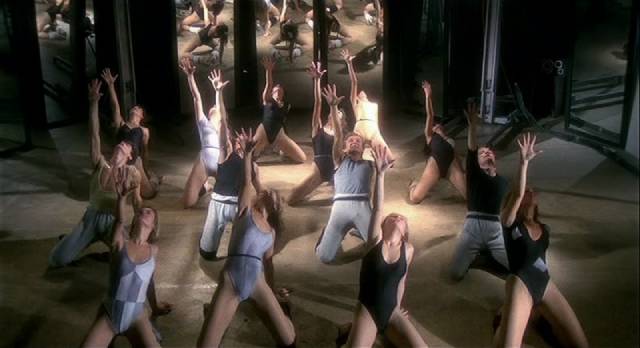

There are excesses in 1984’s Murder-Rock: Dancing Death (as the on-screen title has it), a fairly routine giallo which spends a lot of time on tangential business – set at a dance academy in New York where a group of students are being pushed hard by their teachers in order to provide cast members needed almost immediately for an upcoming show. You know where you are right from the start as the titles play over aerial shots of New York to a throbbing techno track by Keith Emerson, leading into the rehearsal studio where hot young women and men in very revealing outfits sweat mightily through a cheesily erotic number which goes on for what feels like a very long time. As the story unfolds we return repeatedly to these rehearsals, with the camera lingering on legs, breasts, butts and crotches glistening with sweat. It’s a discount version of Flashdance with multiple murders.

I first saw Murder Rock a couple of years ago and didn’t think much of it, but on a recent second viewing on Scorpion’s Blu-ray, I quite enjoyed its period qualities, particularly Emerson’s score. The giallo elements aren’t very original – someone is killing the top dancers in the class – but Fulci goes through the genre paces efficiently and the cast is decent, with Olga Kartalos as the head teacher, Geretta Geretta as her resentful underling, Ray Lovelock as the biggest red herring and Cosimo Cinieri as the cop investigating the murders. There’s a final twist which, as in so many gialli, seems both arbitrary and inevitable. But most of all, there are those long, pulsing dance numbers which remind you of the tasteless excesses of the ’80s.

The big difference between Murder Rock and The New York Ripper, made two years earlier, is the feeling that Fulci wasn’t particularly invested in the former on any personal level. The craft is there, but not the unsettling obsession with the terrible things damaged people can do to one another.

*

Daughters of Darkness (Harry Kümel, 1971)

Whatever positive qualities Fulci’s work may possess at its best, I wouldn’t say he displays elegance. On the other hand, Harry Kümel’s sensuous vampire film Daughters of Darkness (1971) is steeped in elegance, from its moody photography (by Eduard van der Enden) of the off-season Belgian resort of Ostend to the presence of the exquisite Delphine Seyrig as Countess Elizabeth Bathory, an ageless vampire who seduces a young couple in a vast empty seaside hotel. The film’s overarching aura is one of decadence suffused with ennui.

We first meet Stefan (John Karlen) and Valerie (Danielle Ouimet) on a train, newly married and heading towards the coast and a ferry to England. Valerie seems rather naive – she has married Stefan within days of meeting him and, immersed in a romantic glow, fails to note something a bit off. She wants to meet his mother, but he’s cagey … afraid of the reaction he expects because he knows Mother will see Valerie as not good enough for him. When they get to Ostend, bleak and gray under those off-season skies, he puts off the trip to England; when she presses the point, he becomes prickly and we, if not she, sense a potential for violence.

That evening two women arrive in a big vintage car. The concierge, Pierre (Paul Esser), is disconcerted because he recognizes the older woman, Elizabeth Bathory (Seyrig), as someone he saw in the hotel forty years earlier when he was a young bellboy and she hasn’t aged a bit. The Countess invites the couple to join her for a drink and quickly senses the tension between them, just as there’s some undefined tension between her and her companion Ilona (Andea Rau).

On a trip to Brussels the following day, the newlyweds come across a crowd who watch as the police bring a murder victim out of a building, apparently one of a series of young women recently killed. Stefan takes an unhealthy interest, pushing his way to the front in an effort to see the body. Still Valerie is slow to see there’s something wrong. Back at the hotel, they argue again about the trip to England; he finally does make the call to Mother, whom we discover to be a wealthy middle-aged homosexual, casting new light on Stefan’s motives for marrying Valerie and his interest in the murder of young women.

In fact, Stefan finally becomes violent, beating Valerie and forcing himself on her. But as Valerie flees the hotel, the Countess follows and persuades her to stay … while upstairs, Stefan and Ilona attempt a sexual encounter which goes very wrong when he drags her into the shower (although left unstated, this is a reference to a piece of Bram Stoker lore about running water being bad for vampires) – in the ensuing confusion, Ilona ends up dead.

Valerie, being a normal woman, wants to call the police, but the Countess insists this will cause too many problems and the three of them drive Ilona’s body to the seashore and bury her on the beach … after which there’s a ménage à trois back at the hotel, leading to Stefan’s own death. With Valerie entranced by the Countess, and rather disillusioned by men, she herself becomes a vampire, replacing Ilona as companion … at least until a car crash puts an end to the Bathory line, leaving Valerie herself to carry on the decadent tradition of high-living and blood-sucking.

Artfully directed by Kümel (or, as critics at the time tended to dismiss it, arty), Daughters of Darkness arrived around the same time Hammer was discovering the box office potential of lesbian vampires. But although there’s explicit nudity and sex, it doesn’t have quite the same feeling of trashy exploitation. Whether or not you see the difference as art-house pretension, the film feels as if it has more in mind than mere titillation, contrasting brute male violence with seductive female violence, while depicting an aimless wealthy aristocracy preying on those socially beneath them. Sex, class and moribund tradition pathologize a society which has no sense of purpose. And yet the film’s lush visual textures and erotically charged performances seduce the viewer into seeing this pathology as somehow desirable … it implicates us in the decadence it critiques.

Blue Underground’s three-disk limited edition carries over the extras from their previous Blu-ray (except for Vicente Aranda’s The Blood-Spattered Bride [1972]), with the addition of a new commentary by Kat Ellinger. But the real reason to embrace this new edition is the gorgeous 4K restoration scanned from the original negative – the film has never looked this good on video before (judging by screenshots I’ve seen on-line, the 4K UHD copy also included looks even better). There’s also a CD of Francois de Roubaix’s evocative score. It would be nice if they could release a comparable edition of Kümel’s surreal follow-up Malpertuis, also made in 1971.

*

Gialli

Getting away from the supernatural (well, maybe), Vinegar Syndrome recently released the third set in their Forgotten Gialli series. Once again they’ve unearthed a couple of obscure titles, anchoring the set with one higher-profile film – in this case, Armando Crispino’s Autopsy (1975). Once again, these movies aren’t all pure gialli. Francisco Lara Polop’s Murder Mansion (1972), an Italian-Spanish co-production, is more of an old dark house mystery in which a disparate group of travellers all lose their way in thick fog on a lonely country road. Eventually they all find their way to a remote country house which may or may not be haunted and before long people start to die in violent ways. It’s atmospheric, but more Scooby-Doo mystery than true giallo.

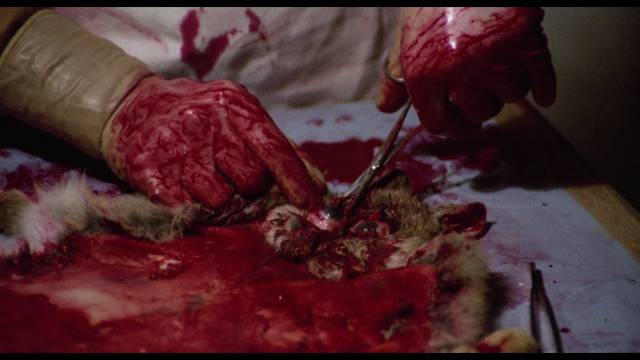

Filippo Walter Ratti’s Crazy Desires of a Murderer (1977) draws on the Italian Gothic, with a woman bringing a bunch of her shady friends to her father’s castle for a weekend. A couple of them are using her for cover in their drug smuggling operation (hiding the contraband in the Asian artefacts she’s brought back for her crippled collector Dad). Meanwhile her mentally disturbed brother spends his time taxidermizing animals, and someone starts killing the guests and cutting out their eyes (this joins Umberto Lenzi’s Eyeball [1975] as the apex of eye-trauma horror).

Crispino’s Autopsy is the best-known and most highly polished movie in the set, and it’s one I’ve been a bit ambivalent about since I first saw it two decades ago when Anchor Bay released it on DVD in 2000. It begins with an intense opening stretch evoking all-out horror which always reminds me of Jorge Grau’s Living Dead in the Manchester Morgue (1975). It’s a scorchingly hot summer, with unusual sunspot activity which seems to be triggering an epidemic of suicides. Mimsy Farmer (who also made gialli with Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci and Francesco Barilli) is a pathology intern working on a study of murders made to look like suicides, while also undergoing some weird personal issues which cause her to hallucinate bodies coming back to life in the morgue and engaging in sex with one another. All of this is very unsettling, so when the film discards these supernatural overtones and becomes an actual giallo, it loses much of the intensity with which it initially grabs the audience.

Nonetheless, it’s still a solid giallo, with Mimsy teaming up with Barry Primus’s troubled priest to investigate the apparent suicide of his sister, which both of them are convinced was actually murder. There are more murders, and there’s a connection to Farmer’s wealthy father, and it’s all set to an excellent Ennio Morricone score.

Each movie in the set gets an excellent transfer and there are one or two interview featurettes on each disk.

*

Hitcher in the Dark (Umberto Lenzi, 1989)

Towards the end of his career, with the Italian industry in decline, Umberto Lenzi, like a number of his contemporaries, tried his hand at making movies in the States. The results didn’t match his best work of the ’70s. Made on the heels of the disappointing slasher Nightmare Beach, Hitcher in the Dark (1989) is neither slasher nor giallo, but rather belongs to the serial killer genre, in which we spend most of our time in the company of a deranged creep with a murderous obsession.

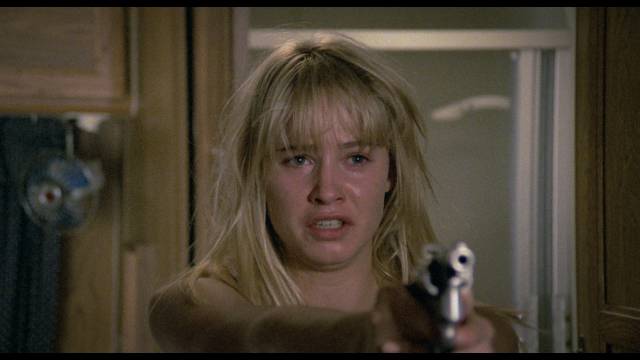

Shot, like Nightmare Beach, in Florida with Spring Break for background, the movie deals with Mark Glazer (Joe Balogh) who cruises the highways in a Winnebago, picking up hitchhikers who resemble (at least in his mind) a photograph he carries with him. We eventually learn that this is his mother and he has a very unhealthy fixation on her. The young women he picks up end up dead and he strips their bodies and photographs them. His latest acquisition is Daniela Foster (Josie Bissett), whom he feels particularly attached to, keeping her alive longer than usual, cutting and dying her hair and keeping her chained inside the camper.

Daniela’s boyfriend Kevin (Jason Saucier), whom she angrily broke up with just before hitching a ride, is on the Winnebago’s trail and there are a number of close calls which generate some suspense, including an encounter with the police who don’t pick up on the weird vibes Mark is giving off. It’s up to Daniela to find a way out of her dangerous situation, but this being a late-’80s movie, there isn’t necessarily going to be a happy ending. The final revelation of Mark’s identity explains how he can get away with his very bad behaviour – wealth does indeed have its privileges.

Once again Vinegar Syndrome provide an excellent transfer from the original negative and add an archival interview with Lenzi and a commentary from Kat Ellinger and Samm Deighan who discuss Lenzi’s career and the ways in which Italian filmmakers used and transformed the genre tropes of the American slasher movie.

*

Cannibals

What would a dip in the large pool of Euro-exploitation be without an encounter with cannibals? In many ways, this is perhaps the most inexplicable of sub-genres, its whole purpose being to rub the audience’s face in gross, transgressive depictions of cruelty. Before the cannibalism became the point – first fully realized in Ruggero Deodato’s landmark film Cannibal Holocaust (1980), in which “primitive” cannibals are pitted against the unrestrained viciousness of “civilized” characters – it was generally used as an exotic flavouring in more conventional adventure movies. Umberto Lenzi’s The Man from Deep River (1972) is generally seen as planting the seed, introducing cannibalism as a peripheral element in an uncredited remake of Elliot Silverstein’s A Man Called Horse (1970), but the movie which really pointed the way ahead was Ruggero Deodato’s Jungle Holocaust (1977).

Again, the frame was a fairly traditional wilderness adventure, with an oil company man leading a scouting team in remote Mindanao, looking for potential drilling sites and becoming stranded in the rain forest. They’re eventually captured by a native tribe which whittles down their number by killing and eating the supporting cast. Eventually the head guy escapes with the help of a native woman who’s taken a fancy to him. As in too many of these movies, the fake gore is supplemented by all-too-real animal slaughter (Deodato said that this was imposed against his wishes by a producer who believed it would boost ticket sales in Asia). Shot in widescreen, Jungle Holocaust, aka Last Cannibal World, retains a foothold in traditional stories of “civilized” white men venturing into dark parts of the world where they encounter innate horrors their society has been designed to suppress.

Even more than Deodato’s movie, Sergio Martino’s Slave of the Cannibal God (1978) situated itself in the tradition of Hollywood adventure movies by casting Ursula Andress and Stacy Keach in the lead roles. There’s something really disorienting about this; it seems natural to see familiar Italian genre actors in this kind of movie, but finding respectable mainstream (semi-)stars trekking through jungles and encountering cannibals seems so much more disreputable. The framing story is conventional – Andress hires pilot Keach to take her into a forbidden area in search of her missing brother – but things are not what they seem and there are deceptions and betrayals along the way before people start to get eaten.

Martino gives all this a polished widescreen treatment, distancing it from the sordid realism the genre was heading towards; despite the graphic content, it seems more like a traditional adventure movie. The narrative framework of conventional adventure was all-but jettisoned by 1980 when Deodato made Cannibal Holocaust and Lenzi played catch-up with Eaten Alive!, though Lenzi really only embraced the new direction the following year with Cannibal Ferox (1981).

in Antonio Margheriti’s Cannibal Apocalypse (1980)

Antonio Margheriti’s Cannibal Apocalypse (1980) seems conventional when compared to what was happening to the genre in that watershed year, but he’s following different conventions. He abandoned the jungle and brought the horror home with heavy-handed metaphorical overtones which bring the movie’s monsters closer to zombies than cannibals. A belated story about the horrors of Vietnam returning to infect suburban America, it deals with three vets who were irrevocably changed by their war experiences – confined in a pit and starving, they resorted to cannibalism to survive and now, back in the States, they have an insatiable urge to eat human flesh. Worse, that desire seems to be contagious.

Margheriti, a pulpy director best known for his ’60s Gothic horrors and space operas, lacks the depth of Deodato and the polish of Martino, but he invests his urban horrors with rough energy and occasionally unsettling imagery. Cannibal Apocalypse is a more effective hybrid than Lenzi’s Nightmare City, made the same year and also pointing to the transition from cannibals to zombies as a more commercially viable genre trope.

All three movies get impressive Blu-ray presentations, with some inevitable fluctuations in quality due to source issues. Code Red’s editions of Jungle Holocaust and Slave of the Cannibal God each include actor interview featurettes and the latter has both the uncensored and American R-rated cuts. Kino Lorber’s disk of Cannibal Apocalypse has a making-of doc, an interview with actor Tony King, a locations featurette and a commentary from Tim Lucas.

*

Nosferatu in Venice (Augusto Caminito, 1988)

Cannibals and zombies are, relatively speaking, fairly recent additions to the horror pantheon. Vampires are more old-school. I hadn’t even been aware of a purported sequel to Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979) until Severin announced their release of Augusto Caminito’s Nosferatu in Venice (1988) a few months ago. Apart from the title and Klaus Kinski’s presence as the titular blood-sucker, there really isn’t any connection between the two movies. Even less so, in fact, because Kinski refused to re-submit to the make-up necessary to transform him into a simulacrum of Max Schreck’s rat-like monster in F.W. Murnau’s original Nosferatu (1922). Perhaps in recognition of this, the movie was originally released in English markets as the more generic Vampire in Venice.

I knew virtually nothing before watching the film, but for some reason was expecting something sleazy and exploitative. What I wasn’t expecting was a good cast giving committed performances, a lush, decadent atmosphere of romance and death, and superb cinematography which presents some of the most hauntingly beautiful imagery of Venice I’ve seen in a movie. There may not be a lot of narrative momentum, but the film creates a rich dreamlike ambience which completely absorbed me.

Which is why I was a bit surprised to learn what a chaotic production it was, with multiple directors coming and going before producer Caminito finally took over himself. Also involved were Maurizio Lucidi, Luigi Cozzi and Kinski himself (who would go on to direct his personal obsession Paganini immediately after). My reaction to the movie seems to have been more positive than most critics’. The film’s dank romanticism is a nice antidote to what Stephanie Meyer did to the vampire myth, evoking some of the unwholesome sexual perversity which defined the monster all the way back to Prest/Rhymer’s Varney the Vampire (1945-47), LeFanu’s Carmilla (1872) and Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

It took me a while to realize the film is set in the present as a sombre Christopher Plummer stands in the prow of a boat crossing the lagoon and entering Venice’s canals. The sight of a modern ship in the distance was jarring, and may well have been a result of careless framing, but eventually it becomes clear, though rather unemphatically, that this isn’t a period film. But by its nature Venice seems timeless and the setting bridges centuries, from a time hundreds of years earlier when the vampire preyed on a noble family, with the resulting curse still looming over the decadent remnants today.

Plummer is the Van Helsing character, tracking Nosferatu in hopes of destroying the monster. He gives the film some genuine gravitas, playing the role without a hint of tongue-in-cheek, while Donald Pleasence counters him as a priest with shaky faith. Looming over everything is Kinski, who exudes an air of decadent rot, an embodiment of perversion which has lived so long that he has nothing but contempt for mere mortals. As an image, his Nosferatu striding across fog-shrouded piazzas or pursuing hapless victims through dank alleys, he’s one of the most impressive screen embodiments of the vampire. While the film is visually sensuous, it’s very different from Jean Rollin’s erotic vampires, evoking a deep sense of rotten decadence rather than an enticing sexuality.

Nosferatu in Venice was one of the nicest surprises I’ve had recently, and to make things even better the disk includes a feature-length documentary, Creation is Violent: Anecdotes from Kinski’s Final Years (2021), directed for Severin by Josh Johnson. Kinski has been well-documented before as a dangerous, disruptive man (not least by Werner Herzog in his My Best Fiend [1999]), but this account of his last half-decade, as reported by many who worked with him, is more horrifying than the main feature. It’s hard to imagine him surviving in today’s climate because the idea of tolerating appalling behaviour because it comes from someone with a prodigious talent no longer flies.

The doc spans from William Malone’s Creature (1985) through Ulli Lommel’s Revenge of the Stolen Stars and David Schmoeller’s Crawlspace (both 1986) to Nosferatu in Venice and Kinski’s own Paganini (1989), and in each instance we get an account of producers, directors and co-stars struggling to accomplish something against the wilfully destructive antics of Kinski, whether simply a refusal to do what a scene required or more disturbingly sexually assaulting actresses just outside of the frame. He comes across as a disgusting creep … and yet when he appears on screen in interview clips he exudes a strange kind of charm, while in the resulting films has that remarkable screen presence. Whatever demons possessed him, making life hell for those around him, he’s transformed by the camera into something fascinating, hypnotic. It’s no wonder he was so effective at playing monsters.

Comments