Recent Arrow viewing, Part Two

by the Lake Michigan Monster (2018)

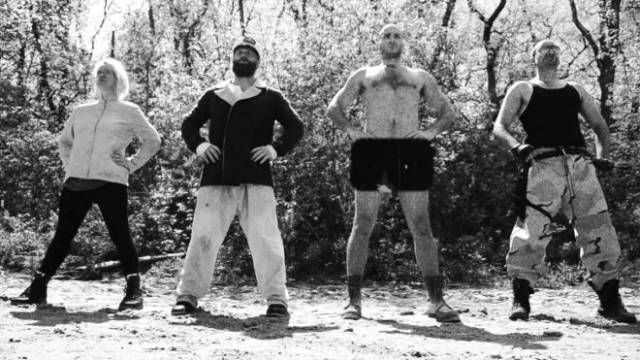

Lake Michigan Monster

(Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, 2018)

Arrow’s William Grefe box set isn’t their only recent nod to low budget regional filmmaking, but it focuses on a long tradition of exploitation which imitates the products of the commercial mainstream. Ryland Brickson Cole Tews’s Lake Michigan Monster (2018) arrives on a different if parallel track. Flaunting its cheapness by evoking poverty row genre films of the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, it also wants to remind viewers of the endearing incompetence of people like Ed Wood. But it carries out its project by making use of modern digital technology to recreate a pre-digital aesthetic.

Pastiche is tricky. Maintaining a balance between homage and mockery takes real skill and for the most part Tews navigates the hazards, though like any such effort that stretches the joke out to feature length (even a short 78 minutes), the film feels padded and the slack parts occasionally undermine the success of the inventive elements. Tews is attempting to do for B monster movies what Guy Maddin has been doing to the traditions of silent and early sound cinema since the 1980s – it’s not surprising to see an acknowledgement of Maddin in the credits. But where Maddin strains for art, Tews aims for slapstick.

With makeshift sets and a small stretch of beach, Tews tells the story of Captain Seafield (Tews himself) and his quest to destroy a monster in, yes, Lake Michigan, which he claims ate his father. Gathering a makeshift crew – sailor Dick Flynn (Daniel Long), weapons specialist Sean Shaughnessy (Erick West) and sonar expert Nedge Pepsi (Beulah Peters) – Seafield sets up on the shore with a series of plans to lure the monster within killing range (all of which involve using Dick Flynn as bait). While there are amusing variations in the plans, the repetition is occasionally irritating before the crew finally enter the lake and track the creature to its lair.

While the surface scenes are deliberately threadbare, the underwater sequences are something else. Using greenscreen and CGI, Tews and visual effects creator (and co-writer and editor) Mike Cheslik, whether deliberately or not, evoke the magical visual fantasies of Karel Zeman. It’s almost as if the filmmakers began the project as nothing more than a goof but then got caught up in the creative possibilities of the technology available to them. While remaining comedic, this final stretch is more like the sincere pastiche of Andrew Leman and Sean Branney’s The Call of Cthulhu (2005).

As broadly conceived as Lake Michigan Monster is, the cast deliver effective performances, sustaining a degree of charm which keeps it afloat. Not likely to satisfy a general audience, its appeal is to those who will appreciate its cinematic references and recognize how far imagination can overcome budgetary limitations. The digital video has been treated to look like a slightly battered black-and-white print, with plenty of detail and fine contrast. And the disk is loaded with extras, including three commentaries (two with cast and crew – one drunk, one sober – and one with critics Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Emma Westwood), several interview featurettes, an effects breakdown, the complete “Dear Old Captain Seafield” theme song, the pilot and first season of Tews and Chesnik’s live action/animation web series L.I.P.S., plus other bits and pieces of ephemera – an impressive package for a movie which cost only a reputed $7000.

*

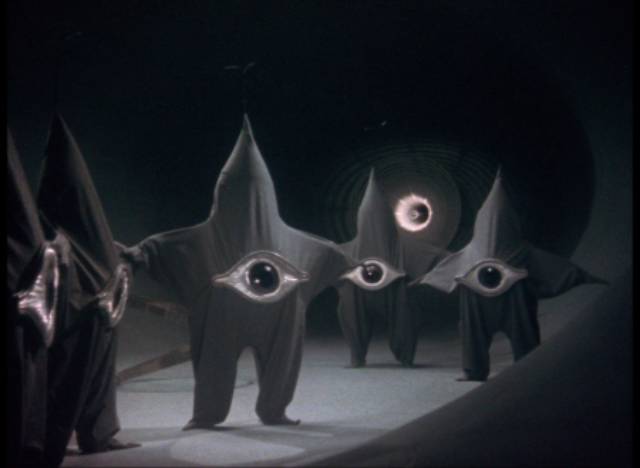

Warning From Space (Kôji Shima, 1956)

Japan’s first colour science fiction movie has a naive charm of its own due in no small part to the design of its alien visitors. Obviously influenced by recent American movies like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Earth vs the Flying Saucers (1956) and It Came from Outer Space (1953), Kôji Shima’s Warning from Space (1956) begins with escalating panic about a series of UFO sightings over Japan. The big question is whether these visitors are hostile or not. The answer comes when one of the aliens takes the form of a popular female singer (Toyomi Karita) who warns Earth’s leaders that the planet is threatened by an approaching meteor. Racing against time, scientists have to develop a weapon to destroy the threat.

So, a fairly standard ’50s sci-fi movie … except for those aliens. Giant one-eyed starfish which look like characters from a slightly nightmarish kids’ TV show, they are funny and ridiculous and undeniably endearing. Despite the movie’s generally serious tone, they add a degree of camp charm which engenders unintentional comedy. Designed by avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto, they seem like a deliberate commentary on the absurdity of the then-current pop culture obsession with the idea of alien visitors. With a script co-written by frequent Kurosawa collaborator Hideo Oguni (Ikiru, Seven Samurai, The Throne of Blood and The Hidden Fortress among others), Warning from Space could well be a self-aware exercise in genre deconstruction … or simply a generic exercise almost upended by silly costume design. Either way, it’s very entertaining.

Though transferred from an imperfect source, Arrow’s Blu-ray looks pleasingly film-like. Stuart Galbraith IV provides a partial commentary and the disk includes the slightly different U.S. cut.

*

Versus (Ryûhei Kitamura, 2000)

Times had definitely changed in the four-and-a-half decades since Warning from Space when Ryûhei Kitamura made his first full-length feature (and third film) Versus (2000). Made with a punk sensibility on a low budget, the movie seems to draw on the strain of Japanese filmmaking exemplified by directors like Takashi Miike and Sono Sion – kinetic and violent – though, unlike those filmmakers’ best work, lacking any real thematic depth; Kitamura’s movie is all about visceral sensation.

Gangsters routinely drive victims out to a remote stretch of forest where they execute and bury them. On this particular day, the gangsters are here to meet a couple of men who have just escaped from a nearby prison. Things are complicated because the gangsters have kidnapped a woman, a development prisoner KSC2-303 (action star Tak Sakaguchi in his debut role) takes exception to. A face-off ends up with several people dead … and the revelation that this forest contains one of 666 dimensional portals scattered throughout the universe, one of whose properties is reanimating the dead.

As the prisoner and the gangsters embark on a running fight, all the previous victims buried here rise from their makeshift graves and, in addition to fighting each other, the guys also have to contend with a seemingly endless supply of zombies. That’s pretty much it; the set-up is an excuse for a series of elaborate fight scenes awash in blood and gore, the woman (Chieko Misaka) present to humanize prisoner KSC2-303, who reluctantly keeps her alive through all the mayhem.

As a showcase for Kitamura’s skill in staging action and using the camera dynamically, Versus is undeniably impressive, but at times it feels long and repetitive – the original theatrical cut is two hours, the revised version Kitamura released in 2004 as Ultimate Versus ten minutes longer. Arrow’s two-disk set contains both versions, with commentaries, new and archival featurettes, and a couple of related short films.

*

The Game (David Fincher, 1997)

You can’t get much further from punk than David Fincher, a filmmaker whose obsession with precision sometimes stifles his work – what was he thinking with Benjamin Button (2008)? I was initially a fan – Alien 3 (1992) is one of my favourite films in the franchise and, even under the weight of all that portent, Se7en (1995) remains a great neo-noir. Fight Club (1999) is terrifically entertaining, but Panic Room (2002) is a ridiculously over-produced B-movie. Zodiac (2007) was frustrating, The Social Network (2010) a polished but superfluous docu-drama. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) was an unnecessary remake which seemed to be uninterested in the core mystery, but Gone Girl (2014) was more engaging than the reviews had led me to expect.

The Game (1997) falls somewhere in the middle, an ultra-polished thriller with an absurd flaw at its heart. Michael Douglas does his best Michael Douglas impersonation as uber-rich and terminally bored businessman Nicholas Van Orton, haunted by memories of witnessing his father’s suicide as a child and now approaching the age at which his father died. His inhumanly repressed emotions have destroyed his marriage and alienated his wild younger brother Conrad (Sean Penn). His existence has no other purpose than to maintain and increase his wealth, though he hardly needs more money.

On his birthday, he has lunch with Conrad at the club and his brother gives him a gift: a card which connects him with a shadowy corporation which runs The Game. What is it? It can’t be described because it’s tailored for each player … but it’s guaranteed to change your life. Nicholas is uninterested until he discovers that the company is opening an office in his building. He decides to check it out, though the tedious and lengthy application process (somewhat similar to the psychological tests Joe Frady undergoes in Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View) irritates him and makes him even more disinterested. That is until he gets a phone call and is told he’s been rejected because of his test scores. Rejection is something he is completely unused to.

But that’s just the first sign that his obsessively ordered life is about to unravel. He has a series of encounters which reveal that he’s no longer in control … it seems that the corporation is subjecting him to a hostile takeover, stripping his assets and forcing him to fight first for social and economic survival, then eventually for his life. It’s fun to watch such a smug, privileged prick brought face to face with forces capable of ruining him, though because he’s been established as such a jerk it’s impossible to feel any sympathy for him as things get progressively worse. In addition, on a dramatic level, as it becomes apparent that everyone he encounters is working for the corporation as part of a plan to destroy him, paranoia slides inexorably towards absurdity.

That absurdity builds to a point of utter implausibility in a climax which erases whatever fun there has been in watching Nicholas’s arrogance stripped away piece by piece. Not only do the mechanics of the climax defy logic (how could those running the Game ensure that Nicholas would jump from the specific, necessary part of the roof?), they defy psychological realism in a way which negates the supposedly uplifting transformation we’re expected to accept in Nicholas – rather than wiping away a lifetime of emotional blockage, being manipulated into supposedly shooting his own brother to death and then committing suicide would surely produce massive PTSD rather than a fresh and happy new outlook on life.

Needless to say, the film looks excellent on the Blu-ray, accompanied by a Nick Pinkerton commentary, a new interview with writer John Brancato and a visual essay by critic Neil Young. There’s also a 4:3 version made for television, reflecting Fincher’s use of super-35mm film to create variable framing. In addition, there’s a DVD which duplicates the contents of Criterion’s edition of the film. The disks come in a slip-cased 200-page hardcover book containing a monograph by critic Bilge Ebiri, as well as several archival interviews and articles.

*

America as Seen by a Frenchman

(Francois Reichenbach, 1960)

Francois Reichenbach was a prolific documentarian, but I think my only previous encounter with his work was indirect – Orson Welles used material Reichenbach had shot of the forger Elmyr de Hory in F for Fake (1973). Reichenbach’s America as Seen by a Frenchman (1960) is an oddity, a kind of proto-Mondo movie in which the French filmmaker roamed about the U.S. for a year-and-a-half shooting an eclectic variety of places and scenes which seem to seek what to an outsider are typically American sights and behaviours, things which illuminate American identity and what makes it different from the European. Not surprisingly, the result is a mixture of insight and cliche. In part it looks ahead to the genre made famous by Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi a couple of years later, while also conforming to well-trodden travelogue tropes (at times it’s reminiscent of Robert L. Bendick and Philippe De Lacy’s Cinerama Holiday [1955]).

There are expansive landscapes and Vegas slot machines; Texans dressing up in 19th Century costumes and spending vacation time following westward trails on horses and wagons; cheerleaders and a stripper school; kids dancing to rock-and-roll and a coy nudie photo shoot. Planes take off from an aircraft carrier and people dance in New Orleans streets, while twins of all ages gather at an annual convention. The commentary, written by Reichenbach and Chris Marker, contains casual sexism and ignores issues of race. The overall impression is colourful but shallow, the film’s chief appeal its striking widescreen photography.

While it seems to be amused by Americans’ sense of themselves as exceptional, acceptance is occasionally tempered by something darker. There are moments when shadows creep in at the edges, particularly in an episode involving juveniles being processed by the police, the bright optimism suddenly seeming illusory, a veneer concealing hopelessness. In the end – and in the light of what was coming in the next few years (the explosion of racial conflict, the horrors of Vietnam, assassinations and political corruption) – America as Seen by a Frenchman seems almost ridiculously naive.

Along with a decent transfer, the disk includes an informative video essay by critic Philip Kemp.

*

JSA: Joint Security Area (Park Chan-wook, 2000)

After a pair of unsuccessful features, Korean director Park Chan-wook hit it big with this thriller, which was controversial in his home country. Situated on the border between North and South Korea, the Joint Security Area, watched over by an international peacekeeping coalition, is a place where the two sides might meet to discuss issues. It’s a volatile place, with soldiers on both sides ready to start shooting at any real or perceived provocation. At the start, Major Sophie E. Jean (Lee Yeong-ae), an officer from the U.N., arrives to conduct an investigation into an incident in which several North Korean soldiers were killed in no-man’s-land. There’s no apparent mystery about who did the shooting. It’s Sgt. Lee Soo-hyeok (Lee Byung-hun); the question is why.

Major Jean is frustrated by Sgt. Lee’s refusal to cooperate, and soon finds that the only Northern survivor of the incident, Sgt. Oh Kyeong-pil (Song Kang-ho), is equally unwilling to talk. The initial story is that Lee was kidnapped and held prisoner on the Northern side of the border and managed to shoot his way out. But a series of flashbacks fill in a more complicated story in which a chance encounter at night initiates a series of meetings during which Lee, Oh and their fellow soldiers develop a friendship, learning that despite their ideological differences they are more alike than not – they’re all Koreans, kept apart artificially by intransigent political systems which maintain their authority by instilling distrust and hatred in their citizens. This, apparently, is a subversive idea and when the friends are discovered it’s safer to invent the story about kidnapping and violence than to admit that they’ve become friends.

Like most of Park’s work, JSA is very polished, with good performances and a firm grasp of suspense which can erupt at any moment into intense violence. While it’s obviously a commercial rather than personal movie, it illuminates the social, political and psychological dynamics embedded in the decades-long enmity between the two Koreas, offering a tentative glimpse of something more hopeful before it finally plunges headlong into nihilistic despair (which reminds us that he went on to make Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance [2002], Oldboy [2003] and Sympathy for Lady Vengeance [2005]).

The transfer is excellent and there’s a commentary from critic Simon Ward, an interview with Jasper Sharp, and a number of archival featurettes about the making and release of the film.

*

in Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales (2006)

Southland Tales (Richard Kelly, 2006)

Richard Kelly remains best-known for his first feature, Donnie Darko (2001), though that cult favourite was first received by audiences and critics with ambivalence. Packed with style and narrative invention, it defied easy categorization and interpretation. But that was exactly what appealed to those of us who became instant fans, and to those who later warmed to it. Strange then that even Donnie Darko’s fans seemed unwilling to embrace Kelly’s follow-up, Southland Tales (2006), a film which echoed DD’s sensibility but was made on a much more expansive scale; where the previous film kept close to a single suburban family, Southland Tales spread out to fill the world with multiple characters and numerous interlocking story lines to create a gleefully comedic apocalypse.

When I first saw it in its brief theatrical run, I found it as exhilarating as Donnie Darko and even more entertaining. Among other things, it was the movie that made me a fan of Dwayne Johnson, who stands out among a huge cast for his comic self-awareness. But as action-movie star Boxer Santaros, suffering from amnesia and in possession of a film script which seems to predict the future, Johnson is just one component of a profligate satire on post-9/11 America, a surveillance state rife with paranoia, political conflict and rapacious corporations which depend on the police to enforce their objectives.

While citizens are constantly watched and controlled by the all-seeing US-IDent, the Treer Corporation has developed an endless source of energy with tidal generators capable of transmitting power to receivers around the world. The problem is that this energy is altering Earth’s rotation and creating rifts in space-time. Among the increasing anomalies are twin Los Angeles police officers Roland and Ronald Taverner (Seann William Scott), who prove to be the key to what is happening because they began as a single man who was duplicated by passing through one of the rifts.

Among the huge cast, in addition to Johnson and Scott, are Sarah Michelle Gellar as porn star/reality TV entrepreneur Krysta Now, Miranda Richardson as the head of US-IDent, Christopher Lambert as arms peddler Walter Mung, Mandy Moore as Santaros’s wife Madeline, Wallace Shawn as the head of Treer, Justin Timberlake as Private Pilot Abilene who watches over Santa Monica beach with a huge sniper rifle (and, yes, he does break out into an elaborately choreographed musical number at one point) … as well as Janeane Garofalo, John Laroquette, Bai Ling, Jon Lovitz, Zelda Rubinstein, Rebekah Del Rio, Cheri Oteri, Amy Poehler, Kevin Smith … all in a relatively low-budget movie.

The plot is complicated, occasionally confusing, and moves at a breathless pace despite the movie’s length. But the level of invention and the richness of the characters are so engaging that any potential flaws are rendered irrelevant. If Donnie Darko is a gem, Southland Tales is the whole jewellery store, chaotic, perhaps a little disorganized, but so packed with ideas and vivid moments that it’s endlessly re-watchable.

Even better, Arrow’s release includes two cuts – the theatrical, and a longer “unfinished” version which was rushed to completion to meet a Cannes deadline. Perhaps not surprisingly, I ended up liking the longer cut even more than the version I was previously used to. The theatrical cut is tighter (at 145-minutes), but there are places where the slightly less polished Cannes cut (158-minutes) allows the narrative to breathe more, lingering on moments which benefit from the extra space. In this it parallels the two versions of Donnie Darko, though the process is reversed; Kelly went back after the fact to create a director’s cut of the latter, again adding some polish, but to my taste diminishing the film – in both cases, Kelly’s preferred versions use more digital effects, which add to a sense of visual clutter, and he over-explains certain ideas which are more rewarding when the viewer is left to discover or intuit them. But at least he’s made the other versions available rather than forcing viewers to watch his own preferred cuts.

The set’s first disk includes the theatrical cut along with a commentary, an archival making-of (33:48), a new three-part retrospective documentary (50:54) and an animated short set in the film’s world. The doc is fascinating, providing a detailed account of the production, troubled distribution and poor reception the film received. Most remarkably, we learn that this epic-scaled feature was shot on a ridiculously tight schedule for a ridiculously small budget. It seems so strange that Kelly has only made three features (this was followed by The Box in 2009), but perhaps not so surprising because his work is so idiosyncratic that production companies (and critics and audiences) remain largely unreceptive. When movies refuse to comply with established genre expectations many people react with defensively closed minds.

*

The Stuff (Larry Cohen, 1985)

There’s no such ambiguity about Larry Cohen’s movies. He’s the genre-movie equivalent of Sam Fuller, much of his work made with a bluntness that borders on crudity, yet at their best they have an energy which infuses genre conventions with freshness and often humour. The Stuff (1985) is one of his most successfully realized and entertaining movies, drawing on a number of obvious influences – Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, 1978), Quatermass 2 (1957), X the Unknown (1956) and The Blob (1958, 1988) – and using them to create a broad satire on consumerism and corporate amorality.

When a strange, creamy substance is discovered bubbling up out of the ground a greedy corporation quickly finds a way to monetize it. This “stuff” is sweet and tasty and highly addictive, so when it’s packaged as a new dessert, the company makes a fortune. Its ingredients remain a secret because it’s considered a proprietary formula, but business rivals want to know so they hire disgraced former FBI agent Mo Rutherford (Cohen favourite Michael Moriarty) to indulge in some industrial espionage.

Meanwhile, addicted consumers are being taken over Body Snatchers-style by what appears to be a sentient organism from deep inside the Earth. Young Jason (Scott Bloom) realizes there’s something wrong after he glimpses the dessert moving in the fridge under its own power; not only is he unable to convince his parents and sibling of the danger, they try to force him to eat the stuff. Running away from home, he’s rescued by Mo and the pair team up as they track the invasion back to the “stuff mine” where it’s being pumped out of the ground and carried away in tanker trucks.

Cohen maintains an effective balance between the sci-fi/horror elements and the satire, which includes pertinent shots at advertising as well as the fast-food industry and more generally at the corporate tendency to poison customers for the sake of profit. The cast generally play things straight enough to make it work as a genre piece, though Paul Sorvino as right-wing fanatic Colonel Malcolm Grommett Spears and Garrett Morris as Chocolate Chip Charlie, an ice cream entrepreneur who suffers a hostile takeover, both play more to the comedy.

Among Cohen’s work, The Stuff has tended to suffer with critics and audiences because the stuff effects are rather rudimentary, but that’s actually a minor quibble given how well the rest of the movie works.

*

A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès, 1902)

It would be difficult to underestimate the importance of Georges Méliès to the formation of cinema as we know it. A successful stage magician, he was attracted to the new technology the moment he saw an early screening of Lumiere actualities. But it wasn’t the reflection of reality that appealed to him; he quickly saw the possibility of using photography to create illusions. He was one of, if not the first to realize that the eye could be fooled by the manipulation of what appeared to be real objects and people in front of the camera. To an audience inured to digital imagery, his now obviously theatrical tricks no doubt appear naive, but at the time they liberated filmmaking from its origins in the literal.

A Trip to the Moon (1902), ostensibly based on Jules Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon (with the insect-like lunar inhabitants obviously inspired by H.G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon [1901]), is a series of incidents with more than a touch of vaudeville in them; a group of scientists board a giant shell which is fired at the Moon, hitting it in the eye. As they explore the lunar surface, a swarm of Moon creatures rush at them, but they manage to get back to the shell and fall back to Earth. At sixteen minutes, the narrative is basic, a mere excuse for Méliès to display a series of in-camera effects.

What makes Arrow’s Blu-ray more than a historical curiosity is the accompanying documentary, An Extraordinary Voyage (2011) by Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange, which provides in its first half an account of Méliès career (also recounted in the accompanying Georges Franju documentary Le grand Méliès [1952]) but devotes its second half to the story of the resurrection of the colour version of Méliès’s film. Thought lost, a single print was found but the reel had fused together like a block of wood. Putting it in a humidifier gradually loosened the outer layers so that they could be carefully peeled off in fragments – brittle and disintegrating, each frame needed to be pieced together and photographed, eventually amounting to thousands of separate images. But then years passed before restoration technology advanced sufficiently to reconstruct the film. This was done by Technicolor’s restoration team, which digitally repaired all the images, filling in gaps from several black-and-white prints and then carefully matching the original colours in what amounted to a digital replication of the original hand-painting process.

I can’t think of a better introduction to the painstaking, labour-intensive task of film restoration.

Arrow’s limited edition comes in a large, sturdy slipcase with a hardcover copy of Méliès’s brief, previously untranslated autobiography, with copious illustrations and annotations by Jon Spira, who also provides a visual essay on Méliès’s effects work.

Comments