Weird Wisconsin: the movies of Bill Rebane

As the more creative independent labels have assumed the major function of keeping physical media alive and thriving, one of the most visible consequences is the unearthing of increasing numbers of fringe filmmakers and what would once have been considered completely disposable movies. Recently, Severin has produced comprehensive sets of the work of Al Adamson and Andy Milligan, with a collection of Christopher Lee’s European productions from the 1960s (including the 24 surviving episodes of a Polish-produced television series) just released. Vinegar Syndrome has an ongoing number of box set series devoted to obscure giallo movies, made-for-TV movies, the films of Mexican director Rene Cardona and low-budget regional horror movies. Indicator has their ongoing Hammer sets (volume six just arrived in the mail), plus the Harry Alan Towers Fu Manchu series, two collections of William Castle movies, and their Columbia noir sets. Companies like Criterion, the BFI, Arrow and Indicator ensure a continuing supply of higher-end movies, but I can’t help being drawn towards these less reputable fringe releases.

Recently Arrow released Weird Wisconsin, something like a companion set to their William Grefé box, this one devoted to Bill Rebane. My knowledge of Rebane was pretty limited – like Ed Wood and Andy Milligan, he seemed generally to be ranked among the “worst”, though that wasn’t likely to put me off, since I’m a real fan of both Wood and Milligan. I knew that Rebane’s best-known movie, The Giant Spider Invasion (1975), is held in contempt, yet another target of smug Mystery Science Theater 3000 ridicule, but I’d previously only seen his odd rural slasher Blood Harvest (1987), which indicated that he was a clumsy storyteller who was nonetheless capable of quirky, unexpected moments.

Rebane, regardless of the intrinsic qualities of his movies, is an interesting character. Born in Latvia, his early childhood was overshadowed by the Second World War and the presence of the Nazis and the Red Army. Emigrating with his family to the U.S. in the early ’50s, he later moved back and forth between the States and Germany, receiving education in both countries and establishing business ties which enabled him to pursue a career in film production despite being chronically limited by inadequate resources. He studied drama at the Art Institute of Chicago, learned film production in Germany, and attempted to introduce a specially designed 360-degree projection system to American exhibitors while still in his early twenties – a kind of more ambitious proto-Imax, which didn’t manage to overcome certain technical limitations.

In the early ’60s, he decided to get into production, making some short films which formed the basis of an on-going industrial/promotional business. His first attempt at a feature was fraught with problems, largely due to financing issues, though also rooted in inexperience. Begun as a sci-fi horror movie called Terror at Halfday, production proceeded in fits and starts, the script being revised repeatedly as actors dropped out and had to be replaced. Eventually Rebane gave up and turned the existing footage over to his friend Herschell Gordon Lewis, who completed it as Monster a Go-Go (1965), a disjointed – not to mention demented – throwback to ’50s sci-fi B-movies with its roots in Val Guest’s The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Robert Day’s First Man Into Space (1959), though in terms of quality it’s closer to Robert Gaffney’s Frankenstein Meets the Spacemonster (1965), with which it would make a fine party double-feature.

Strangely, despite its amateurishness and absurdity, or maybe because of it, I found Monster a Go-Go kind of charming and entertaining. A space capsule returns to Earth and it seems that its pilot has been mutated by radiation and is wandering the countryside killing people with his deadly touch. As an indication of the movie’s conceptual problems, the monster is played by 7’6” Henry Hite while the tacky capsule is about four feet high and looks like it might comfortably contain a large cat. Because of the protracted production and erratic availability of actors, characters come and go, seeming to be important only to disappear without explanation.

Eventually, the monster ends up in the sewers beneath Chicago with the military in pursuit. Somehow Rebane managed to get a big stretch of central Chicago closed off to shoot the climactic sequences, but it ends up with a strangely enigmatic denouement. The monster disappears into the tunnels and the pursuing soldiers turn back as an announcer tells us that the capsule has been discovered somewhere else and the pilot has returned safely … with no indication of who or what the tall deadly menace might actually have been. This odd randomness, imposed by the lack of material resulting from a never completed shoot, carries over into other Rebane movies, taking on the quality of a creative signature. Contingency becomes an expression of directorial intention.

In the late ’60s, Rebane moved from Chicago to northern Wisconsin, buying some rural land and establishing his own studio, which he called The Shooting Ranch. For the next two decades, the area gave a distinctive character to his movies – as the Florida Everglades did to Grefé’s and Pittsburgh and environs did to George Romero’s. This is one of the appeals of regional filmmakers, a sense of place distinct from the generic “America” favoured by Hollywood.

Location and the necessity of accommodating limited budgets give an interesting quality to Rebane’s work. No doubt recalling the problems he faced with his first feature, Rebane’s second movie was tailored specifically for the circumstances. How do you tell a science fiction story about the end of the world on no budget? You isolate a handful of people in a remote house and occasionally feed them reports of catastrophic events occurring elsewhere. After all, that worked remarkably well for Romero when he made Night of the Living Dead (1968). While Rebane lacks Romero’s formidable filmmaking skills, Invasion from Inner Earth (1974) is more effective than I had expected, given its reputation.

A brother and sister with a lodge in northern Manitoba are hosting a university research team, unaware that something is happening in the outside world. With the trip over, it’s time for the team to leave and the brother flies them out to the nearest airfield; but there’s no response from the control tower. As they approach for a landing, they finally hear a warning not to land … a plague is wiping everyone out and they should head back to the wilderness. Diverting to a smaller airfield, they find it deserted; when they try to use the shortwave radio there, a strange red light manifests. They decide to fly back to the lodge and wait … and wait.

Most of the movie deals with the growing frustration and tension within the group as they receive occasional cryptic messages by radio, suggesting that some alien force is cleansing the world of its human population by spreading a deadly contagion. One of the students steals the plane, but it explodes as it climbs from the landing strip by the lodge. Another sets out on a snowmobile, trying to reach the nearest settlement, but he runs into the red smoke which carries the plague. In the end, Rebane concludes things almost as cryptically as in Monster a Go-Go; the sister and the leader of the research team hike out of the winter wilderness and are transformed into two young children who walk hand in hand up a verdant hillside towards what appears to be a flying saucer in the distance – perhaps a new Adam and Eve destined to replace Earth’s unworthy human inhabitants.

Although there are a few brief moments depicting the end of civilization as panicked people flee through city streets filled with drifting red smoke, the movie determinedly avoids conventional action. Rebane manages to transform limitations into something positive, in part thanks to some decent performances, in part due to a convincing evocation of the tension between fear and boredom as the characters sit around chatting at the lodge wondering what’s happening beyond their own small area of experience.

He followed this with The Giant Spider Invasion (not included in the set) but then returned to a similar set-up with The Alpha Incident (1978), again isolating a handful of characters in a single remote location while bigger things are occurring elsewhere. In this case, a Mars probe has returned contaminated with some kind of life form similar to a virus. As a team of scientists work to identify the organism and look for a possible antidote to its deadly effects, the authorities decide to send the bulk of it to a remote secure facility … but for safety’s sake, they don’t want to risk flying it. Instead they send it by rail without informing anyone of what the train is carrying.

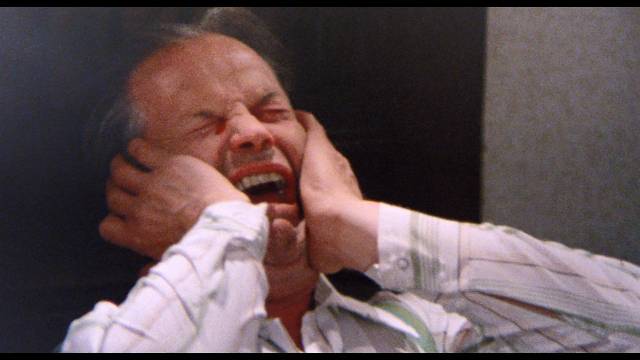

When a curious train guard decides to look inside the sealed containers, he breaks some vials and is exposed. The scientist/security agent accompanying the shipment reports the breach and is ordered to quarantine himself with the guard and several workers at a remote station where the shipment was supposed to be picked up by another train to continue to its destination. The agent, the guard, the station manager and his secretary, and a belligerent worker are stuck together in the office and waiting room where once again the small group, under increasing pressure, find themselves getting on each other’s nerves. Things get worse when they’re informed that they have to try to stay awake because the alien pathogen will kill them if they sleep.

With these very limited narrative parameters, Rebane manages to create a strange mixture of boredom and tension which may not be to every taste, but I found it unexpectedly effective. By this point in the set, I was beginning to appreciate his almost perverse resistance to conventional dramatic rules, a deliberate kind of anti-action which might be more familiar to theatre than it is to the movies. This is the opposite of the tendency of low-budget filmmakers to try and overreach by aiming for more action and excitement than their resources can support.

Rebane’s next two features are missing from the set, both cryptid-based horrors – The Capture of Bigfoot (1979), a self-explanatory title, and Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake (1981), which seems to be about something like a humanoid frog. These were followed by a switch from sci-fi monsters to the supernatural. Perhaps not coincidentally, Rebane had rented his studio to Ulli Lommel for the latter’s production of The Devonsville Terror (1983), about a small New England town living under a curse dating from colonial times and the persecution of local witches. Made immediately after Lommel’s film, Rebane’s The Demons of Ludlow (1983) is about a small town living under a curse dating from … um, colonial times … and the persecution of witches…

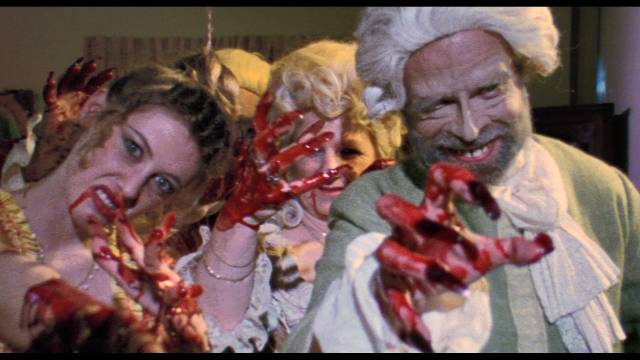

I haven’t seen Lommel’s movie (which, like much of the director’s work, has a poor reputation), but Rebane’s is fairly atmospheric if somewhat sluggish. There’s a touch of John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) in the story of a town celebrating its two-hundredth anniversary which finds itself being attacked by malevolent, murderous ghosts seeking revenge on the descendants of the people who persecuted them in days gone by. A young reporter who was born in the town returns to cover the festivities, accompanied by her photographer, and soon realizes that something bad is happening. The catalyst is an antique piano which has just been returned to Ludlow by the descendants of the exiled founder; when it’s played, a demonic force is released and the ghosts of decadent, hedonistic members of the original community reappear in a particularly material form – they kill with guns and swords.

There’s nothing particularly original about the movie, and Rebane’s pacing is problematic, to say the least, not to mention his poor grasp of day/night continuity. On that basic level, it’s a mess … but the movie has undeniable atmosphere, largely due to having been shot in the depths of a very cold Wisconsin winter. Again, there are some decent performances and the setting remains visually engaging.

Having made my way through the set’s first two disks with their four features, each accompanied by a short, self-aware interview with Rebane (now in his early 80s), along with several of his short films, an interview with Kim Newman and a visual essay by Richard Harland Smith about The Alpha Incident, I found myself more appreciative of the filmmaker than I’d expected. By this point, I’d already placed an order for The Giant Spider Invasion[1] and tracked down a copy of Rana on-line; I also bought an ebook copy of Rebane’s 2008 UFO novel From Roswell With Love (which unfortunately turned out to be so badly formatted that it’s unreadable). Then I tackled disk three and the glow faded a little. The final two movies aimed more for comedy than the earlier films, which tended towards a grim seriousness. For my taste, Rebane’s sense of comedy is not terribly strong and these two movies proved to be a real slog to get through. Which seems a little puzzling since I hadn’t had a problem with the narrative inertia of the first four movies.

The Game (1984) is tonally jarring. Structurally it resembles a typical ’80s body-count horror movie, but the set-up is played as a kind of joke. Three bored millionaires play “the game” once a year at a big, empty resort hotel. They gather a random group of people together and challenge them to stay for the weekend, the last to remain getting a million dollar prize. The thing is, these contestants will be faced with various scares – beginning with a tarantula in the soup at the opening night dinner as the rules are explained. There are a number of problems, not least that the characters are barely sketched in; then there’s the vagueness of the game itself. If it’s just to be a series of jump scare gags like the spider in the soup, it’s really not much of a challenge. But when people begin to disappear and/or die, it no longer makes sense for the “contestants” to stick around … but then maybe no one is really killed and the apparent deaths are just more gags … and then the tables are turned and the three millionaires are under violent threat from their pissed off victims … and maybe in the end they’re left for dead … except maybe that’s just another gag…

The Game swings back and forth between reiterating slasher tropes and mocking those same tropes, but without ever clearly establishing its intentions. More than in any of the earlier films, there’s nudity and sex – the sexual content in The Alpha Incident is kind of uncomfortable, but that works with the narrative; here you feel that it’s being tossed in purely as a commercial necessity and it seems that Rebane isn’t particularly comfortable with shooting it. Like Monster a Go-Go, everything essentially dissolves into vague uncertainty at the end as if no one really knew what the point of it all was.

Having made a somewhat more successful slasher after this with Blood Harvest, Rebane abandoned horror altogether with the final movie in the set. Twister’s Revenge! (1988) looks exactly like what it is – a movie inspired by a visit to a monster truck rally. The thin, quickly abandoned narrative is nothing more than an excuse for smashing and blowing things up. A lot of vehicles are wrecked, but Rebane gets the most production value out of finding buildings due for demolition through which he could crash monster trucks and even a tank.

The truck named Twister is equipped with a computer control system which has become sentient and three dumb rednecks decide they can get rich by stealing the AI. They don’t figure on the vehicle’s ability to fight back … and that’s it. A series of chases and vehicular mayhem gags involving a big truck, its owner and his computer-whiz girlfriend, and three rural stooges. As The Demons of Ludlow seemed to have missed its natural time, coming as the market was making its decided turn towards slasher movies, Twister’s Revenge! has its roots in the highway action comedies which hit their peak almost a decade earlier with Smokey and the Bandit (1977) and The Cannonball Run (1981). But no one here has the easy charm of a Burt Reynolds. While some of the stunts are impressive, I barely made it through to the end.

*

So, in contrast to the Grefé box set, which got more interesting as it progressed chronologically through the filmmaker’s career, Weird Wisconsin starts out interesting and ends weakly. But I’m glad Arrow has put it out, because it’s yet another illustration of what determined people have been able to do outside the industry mainstream, bending familiar genres in idiosyncratic directions. And like the Grefé set, this ends with a feature-length survey of the filmmaker’s career, Who Is Bill Rebane? (2021), this one made by David Cairns. In addition, there’s a lengthy essay by Stephen Thrower in a small hardcover book included in the set. Again, learning more about the filmmaker’s life inspires a greater appreciation of what he managed to accomplish, warts and all.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) I watched The Giant Spider Invasion as soon as it arrived and thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s an unabashed throwback to ’50s monster movies in which a small town is beset by an alien threat – here mostly actual tarantulas until the titular “giant spider” shows up. Although inevitably much ridiculed, I was actually quite impressed with what Rebane and his crew managed to do on a very small budget. The spider was built on a Volkswagen chassis, with legs operated by crew members inside somewhat like slaves rowing an ancient Roman galley. It might be rather stiff, but it offers a few striking images as it moves down the town’s main street or across a hillside in the distance. Up close, the moist mouth into which it shovels hapless victims is suitably unpleasant. Rather than fallout from nuclear tests, this creature shows up because a small black hole(?) crashes in a Wisconsin farmer’s field, creating a doorway to another dimension through which the arachnids both large and small enter our world. The Dark Force Blu-ray has a surprisingly good image, and includes interviews with Rebane and actor Robert Easton. (return)

Comments