Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975): Criterion Blu-ray review

In a career lasting a quarter-century, Andrei Tarkovsky made only seven features, the final two in exile, funded by European sources. Although from the early 1960s to the late ’70s he had to fight with the bureaucrats of Soviet film production, it’s one of the paradoxes of that state-run system that he managed to make those first five features against often intense opposition. The Soviet industry was not governed primarily by commercial concerns; more important were ideology and propaganda. As a result resources were effectively unlimited, making possible vast productions like Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1965-67) and Tarkovsky’s own epic second feature Andrei Rublev (1966). The irony was that, having funded Tarkovsky’s work, the bureaucrats as often as not disliked the results, holding back release, forbidding entry into foreign festivals, and repeatedly condemning him for being too personal and elitist. Baffled by his fourth and most personal film, Mirror (Zerkalo, 1975), they declared that it was too intellectual, too pretentious, and yet when it was released in the Soviet Union, many (ordinary) people found in it an emotionally resonant reflection of their own experience – a reaction which highlighted the disconnect between state-mandated content and attitudes and the lives of the Soviet population.

I became aware of Tarkovsky myself in the early ’70s when his adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris was released in the West (to mixed reviews). As an admirer of the book, I was eager to see the film, finally getting a chance in London during the summer of 1975. Although looking back I realize I only grasped some of what Tarkovsky was doing, I immediately fell under its sway, drawn in by its allusive imagery and its strange rhythms. Five years passed before I had a chance to see more of his work – in Hong Kong, I saw Andrei Rublev in December 1980 and Stalker (1979) in January 1981 – and several more years passed before I saw both Mirror and Nostalghia (1983) in London during the summer of 1985. The only one of his films I actually saw as a new release was Sacrifice, in the Fall of 1986, shortly before Tarkovsky’s death. Sadly, I’ve never had a chance to see his first feature, Ivan’s Childhood (1962), on a big screen, having first watched it on a New Yorker Films VHS tape in the early ’90s, and subsequently many times on various DVDs.

These encounters with Tarkovsky’s films, scattered across more than a decade, may appear to be a rather small thread running through my experience of watching literally thousands of movies during the same period, and yet he holds a key place not only in my comprehension of cinema as an art form, but in my perception of the world outside of film. In a very real and important way, Tarkovsky taught me how to see. Other filmmakers have contributed to this – Antonioni, Angelopoulos, Malick – but none more forcefully or with more lasting effect than Tarkovsky.

How to explain this? Film is a plastic art, rooted in the material world (well, it was before the advent and overuse of CGI), so I shy away from any claims of the mystical; and yet Tarkovsky, like Bresson, seemed able to capture something beneath the materiality of the world, a kind of animating energy. He himself associated this with the Christian God, but although his work frequently references Christian iconography the films are not bound to church dogma. I may be emphasizing this point because, being an atheist myself, I don’t share Tarkovsky’s religious beliefs. Within the context of the films, while characters may speak of God and faith, the visual qualities of what he shows us can just as easily be attributed to animism, an evocation of vital energies which make the world itself a living organism within which human beings are just one aspect of this ebb and flow of energy.

How does Tarkovsky make the invisible visible? Choices of story and theme have some bearing, of course, but conventional ideas of narrative became increasingly less important to him. Ivan’s Childhood and Andrei Rublev most closely resemble conventional storytelling, but even there moods and psychological states begin to take precedence. More important are his visual strategies, which use a camera seemingly untethered from the narrative and characters. Tarkovsky’s camera is almost always in motion, but that motion is not governed by what’s going on in a scene. It seems to have a mind of its own, exploring something which exists beneath or beyond the immediate concerns of the people who temporarily inhabit this visual space, with characters being caught almost by chance as they go about their own business. This visual dance is one of the great aesthetic pleasures of Tarkovsky’s work and it was already being manifest as early as Ivan’s Childhood in the scene between Galtsev and Masha as they flirt with one another in the birch woods.

But if the camera seems only tangentially interested in the characters, what is it focusing on? More often than not it’s details of the natural world – the way wind moves through a field of tall grass or bends the branches of trees; the way plants sway with the flow of water; the way rain suddenly falls in a garden or a muddy street. Objects seem to have their own autonomous existence, moving without human agency. In Tarkovsky’s films, the play of elements is a constant and he repeatedly breaks down seemingly natural boundaries – in many of his films rain falls inside rooms, blurring the border between interior and exterior, and fire and water occupy the same space. This blurring results in such startling images as the protagonist’s dacha in Nostalghia reconstituted within the tall stone walls of a ruined cathedral, a poignant evocation of what has been lost through displacement, existing now only as vivid memory.

The natural world is a vital factor in Tarkovsky’s films and one theme he returns to repeatedly is the emotional and psychological cost of separation from that world. In Solaris, Kris Kelvin lingers in the landscape around his father’s dacha before he leaves on his journey to the planet Solaris, a journey which Tarkovsky represents as a long drive into a great city, nature replaced by buildings and highways. Once on the planet, the sentient ocean probes his mind and seeks to reconstitute what is most meaningful to him – first his dead wife Hari, and by the end that landscape in which he began. In Stalker, the title character leads his clients out of a world which has been killed by human activity, a bleak industrial wasteland, and into the Zone, a mysterious place reclaimed by a Nature which the characters no longer comprehend. But no film is more elemental, more steeped in the natural world, than Mirror.

Mirror (Zerkalo, 1975)

In the film’s prologue, we see a boy (whom we will eventually identify as Ignat, the son of the unseen protagonist) turn on a television set on which a therapist conducts a session with a young man with a severe stutter. Using hypnosis, the therapist instructs him to move all the tension from his blocked speech centre into his hands, making them rigid and immovable. Then she abruptly releases him from the hypnotic trance and he’s able to speak freely. If this seems a bit too simplistic (and miraculous), it nonetheless provides a metaphor for what we will see unfolding in the film, the breaking down of the protagonist’s emotional blocks, releasing a flood of memories through which we come to understand how he became the (flawed) man he is; but more importantly we witness the life of his mother and the ways in which her experience is interwoven through the 20th Century history of Russia. Mirror is a meditation on how time and place shape individual lives.

Although the film avoids linear narrative, it depicts four key periods: there’s an idyllic early childhood in the mid-’30s, the stresses of the Great Patriotic War, the oppression of the early 1950s under Stalin, and the contemporary period from which all else is observed by the unseen Alexei (voiced by Innokenti Smoktunovsky) who may be dying, contemplating a sense of failure which is embodied in a broken marriage and a son with whom he has difficulty connecting. That relationship with Ignat is a kind of reiteration of his relationship with his own father (Oleg Yankovsky), who abandoned the family in 1935. Tarkovsky incorporates his own father, who abandoned his family when Andrei was a child, into the fabric of the film, with the poet Arseny Tarkovsky reciting several of his poems on the soundtrack as a counterpoint to the images.

The young Alexei (Ignat Daniltsev, who also plays Ignat in the contemporary sequences) remains something of an observer, bearing witness to his mother’s struggles to make a home and life for the family after the father leaves. As portrayed by Margarita Terekhova (who also later appears as Alexei’s ex-wife Natalia), the mother keeps her own emotional struggles to herself, providing a strong foundation for her children even as life grows less secure and more demanding. During the war, when she visits a better-off neighbour to sell her few pieces of jewellery, she has to contain her sense of humiliation in front of Alexei. Later, during the bleak post-war period, the paranoia of late-Stalinism is even more isolating.

In one of the film’s strongest sequences, she hurries along bleak streets in heavy rain, driven by fear. Arriving at the state printing house where she works as a proofreader, she becomes increasingly agitated, searching for the manuscript she was working on the previous day. This morning, she suddenly became certain that she had seen an error which could have devastating consequences, flipping through the manuscript to find the page even though the foreman says it’s already too late as the print run has been completed. Finding that there is actually no such error, the sudden release of tension triggers a harsh attack from her co-worker Elizaveta Pavlovna (Alla Demidova). In this one sequence, Tarkovsky evokes the emotional and psychological layers of life under a repressive totalitarian regime, the internalized fears and insecurity and the broken connections between individuals which have been deliberately created to prevent opposition to the rulers’ power.

The broken idyll of the ’30s, the humiliations of the war years and Stalinism, give way eventually to the personal problems of Alexei’s adult life, the irritations of his relationships with his aging mother and his wife; by implication, existence has become easier in the early ’70s, permitting a more introspective approach to life, which paradoxically seems less rich and meaningful than during those earlier periods. Alexei continually circles back to that earlier time – a time when responsibility fell on his mother’s shoulders, before he had to manage his own life. By implication, he seems to lack the strength of his mother and in some way resents this.

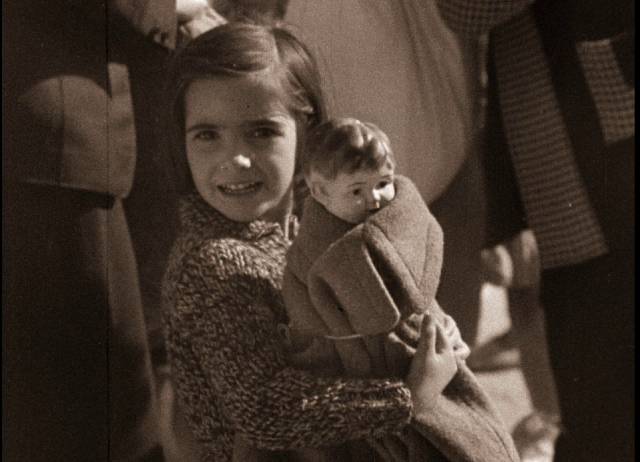

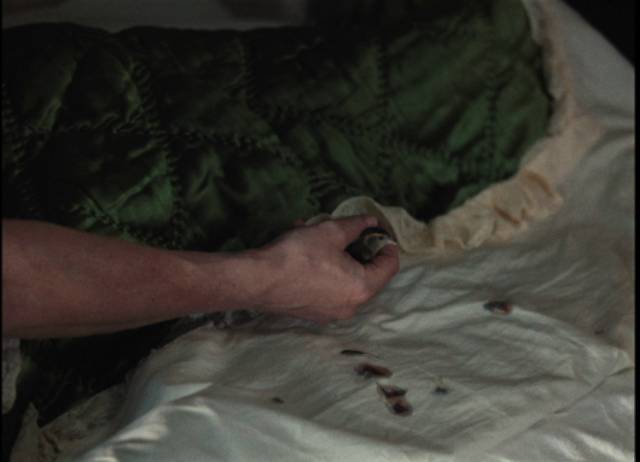

Early in the film, over the phone, he asks her about that time in the ’30s, uncertain of his memories, and becomes irritable because she’s concerned about his health … yet by the end, having reviewed his life, he has essentially given up. In a typically oblique Tarvovskian moment, we see his hand take hold of a small bird huddled on his bed covers and lift it up. Its flight suggests the moment of death and we find ourselves back at the house in the country, Alexei and his little sister small children again, walking across the field with their mother who is now the old woman of the contemporary sequences, while in the distance we glimpse the mother as she really was back in 1935, both periods collapsing into one another as the camera backs away into the woods, retreating from both the world and Alexei’s memory of it.

*

In all his films, Tarkovsky dissolves the boundary between “dream” and “reality”, but Mirror is the most oneiric of all, as memories ebb and flow in the mind of a possibly dying man trying to come to terms with events of his life and his own behaviour. Although there’s ultimately an air of defeat, the film is full of some of the most beautifully realized sequences in cinema – from the opening with the mother sitting on a fence smoking a cigarette, watching a man approach across the meadow for an oddly intrusive encounter (“It’s all right,” he says, “I’m a doctor,” asserting a casual sense of male privilege), which culminates in a remarkable moment as he walks away and pauses to look back as a gust of wind sweeps across the grass and rushes up the slope towards the mother; to the burning of the barn during a rain shower; to Alexei among other boys being trained on a shooting range during the war, one of the boys being a traumatized survivor of the siege of Stalingrad; on to the incident at the printing house, so deeply infused with unspoken fears; and the enigmatic scene in which an unknown woman appears and asks Ignat to read from a letter written by the 19th Century poet Pushkin in which he expresses conflicted feelings about his country, the scene ending with the equally enigmatic disappearance of the woman, who leaves only a small circle of condensation fading away on the polished surface of the table where her teacup had rested.

The personal moments are infused with mystery, yet they are embedded in a larger historical context through documentary footage of the Spanish Civil War, the Soviet army trekking across a lake towards German forces, the Chinese Revolution and a border dispute, a massive balloon carrying its crew to a high altitude… This material is evocative of the struggles, conflicts and triumphs which played a part in shaping the lives of the family at the centre of the film. Mirror condenses both macrocosm and microcosm, interior and exterior into a work which somehow portrays the flow of individual lives in both their own specificity and their shared generalities. No wonder so many in its audience saw a reflection of themselves.

*

Although conceived on an intimate, autobiographical scale, Mirror was in many ways the most difficult film Tarkovsky ever made. Although specifics vary in different accounts, it went through somewhere between a dozen and twenty completely different versions during the editing, with Tarkovsky and co-writer Alexander Misharin repeatedly breaking it down and re-ordering the sequences as they tried to make it work as a unified whole. They had almost given up hope before, in a final attempt, it came together into the version we now have. And to be honest, there remains one particular element which doesn’t quite fit – there’s a contemporary sequence in which Alexei and Natalia are at a gathering of Spanish exiles who settled in Russia after the Civil War. While there’s a suggestion that Alexei’s father had left the family to go and fight in Spain, giving some personal meaning to that conflict, this party scene feels somewhat extraneous. Interestingly, it’s mentioned specifically in a documentary on the disk dealing with cinematographer Georgy Rerberg; Rerberg apparently was in the habit of shooting scenes he didn’t like with less creative commitment and he didn’t like this particular scene – if true, this might explain why the scene is so much less evocative than the rest of the film.

*

Mirror shares the first disk in Criterion’s set with a feature-length documentary by Tarkovsky’s son, Andrei A. Tarkovsky. Although listed as a supplement, Andrei Tarkovsky: A Cinema Prayer (2019) is more of a co-feature, using excerpts from all of Tarkovsky’s films and new imagery which echoes those films, along with archival footage of Tarkovsky at work and his own voice from various interviews to convey his personal beliefs and his theories of filmmaking. It’s a superb condensation of Tarkovsky’s diaries and his book Sculpting in Time, published in 1985, the year before his death. The documentary is an excellent critical introduction to the films, with the added value of footage of Tarkovsky at work with actors and crew on many of the films.

*

The disks

Criterion’s two-disk Blu-ray set is mastered from a new 2K restoration from the original negative, provided by Mosfilm, and the image is excellent, with more natural colour than most previous editions, a film-like texture with a great deal of detail and nicely layered contrast. The mono soundtrack supports dialogue and natural ambiences very well and gives particular support to the nuanced use of music – the original score by Eduard Artemyev as well as selections from various classical composers.

The supplements

As mentioned, disk one includes the feature-length documentary by Tarkovsky’s son (1:42:07), while the second disk contains almost three hours of additional new and archival documentaries. There are two brief clips from French television (4:19, 3:31) in which Tarkovsky is interviewed about Mirror at the time of its release in that country in 1978.

An interview from 2004 with co-writer Misharin (32:34) is enormously engaging as well as illuminating about Tarkovsky’s creative process; the pair actually began working together on the project while Tarkovsky was making Andrei Rublev, but it got sidelined due to resistance from the authorities – Misharin resented Tarkovsky making Solaris instead, but rejoined the project when new bureaucrats approved Mirror in the early ’70s.

Islands: Georgy Rerberg (52:08), a TV documentary from 2007, covers the troubled career of the cinematographer, who did brilliant work but seems to have fallen out with every director he worked with, ending relationships with Andrei Konchalovsky and Tarkovsky on highly acrimonious terms. He appears to have had a habit of telling filmmakers that what they were making was shit.

A new interview with composer Eduard Artemyev (22:11) details his working relationship with Tarkovsky, which involved using music more as an element of a film’s soundscape rather than as traditional score. In fact, Artemyev himself describes his work on Solaris, Mirror and Stalker as that of a sound designer rather than a composer.

The Dream in the Mirror (2021, 53:56) is a new documentary about the film by Louise Milne and Sean Martin, which uses new and archival interviews as well as Tarkovsky’s own written words to recount the genesis and production of Mirror. To be honest, I found this a bit too self-consciously arty (dividing up Tarkovsky’s texts between male and female narrators, often within the same passage, is initially confusing) in ways which certainly don’t reflect Tarkovsky himself. Still, there are many useful insights from the various interview subjects who include some of Tarkovsky’s collaborators as well as his sister and a number of critics and academics.

The substantial booklet (88 pages) includes an essay by critic Carmen Gray, plus reprints of “Confession”, the original proposal submitted by Tarkovsky and Misharin in 1968, and “A White, White Day”, not exactly a script, nor a transcript of the finished film, but rather a prose analogue of the film, the version here a final revision made by Tarkovsky in 1984.

Criterion’s edition of Mirror is a welcome addition to their collection of Tarkovsky’s works, and the massive addition of four-and-a-half hours of illuminating supplements puts this in line to be their most significant release of 2021.

Comments

Important and great article on andrei tarkovsky’s films