Bill Duke’s Deep Cover (1992): Criterion Blu-ray review

Black Cinema has always, inevitably, been political. From Oscar Micheaux and others working with tiny budgets far from the mainstream in the 1930s and ’40s to radical filmmakers like Melvin Van Peebles and Bill Gunn whose work in the early ’70s unleashed the flood of blaxploitation in that decade, Black Cinema stood in opposition to a society which was at pains to repress and contain Black experience. In Hollywood, Black roles were largely relegated to servants and comic relief when not being presented in monstrously racist terms as in Birth of a Nation (1915) or patronizingly racist terms as in Gone With the Wind (1939).

Things improved only superficially as post-war liberalism took tentative steps to acknowledge the presence of People of Colour in post-war American society, most significantly perhaps in the work of Stanley Kramer. But what might be seen as best intentions were nonetheless hugely problematic in films like Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) or Ralph Nelson’s Lilies of the Field (1963), where an apparent attempt to bring Black characters into the mainstream actually sought to reassure white audiences that those who had long been depicted as the menacing Other were actually not dangerous at all. Rather than being afforded full autonomy, these characters were still seen as Other but no longer as a threat to a complacent white certainty of natural dominance.

Even this liberal project couldn’t overcome centuries of prejudice and the fear of Blackness which was a corollary of repression. Whether subconscious or not, there was always an implicit recognition that the brutalization of People of Colour inevitably engendered a threat to white dominance – a recognition which still plagues American society – and in an endless cycle, the fear of a reaction to this brutalization generates further brutality, justified by the projection of criminality onto all Black people. Caught between that image of criminality and its mirror in non-threatening submission, there was little room for a fully autonomous identity and so the anger of a filmmaker like Van Peebles came to be expressed through a ferocious embrace of violence as a response to repression, not as criminal transgression but as a revolutionary act. In Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Van Peebles has no interest in being admitted into mainstream society – he instead wants to tear it down.

That anger, engendering an act of refusal, fuelled blaxploitation even as the genre was appropriated by corporations who recognized the profit potential in an untapped, unserved Black audience, but as often as not the revolutionary impulse disappeared and the idea of a criminality inherent to Black communities reinforced the stereotype of Black people menacing the dominant society. That type of exploitation largely burned itself out by the end of the decade, but the energy didn’t disappear completely and it re-emerged in a flood of movies by young Black filmmakers in the early ’90s. Movies like John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991), the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society (1993) and Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) are markedly different from those of the ’70s, asking forcefully what space is available for People of Colour in what remains a racist American social and political landscape. These filmmakers and their movies seek to define their own terms rather than to adapt to the terms which have long been laid down by white-dominated popular culture.

Bill Duke’s Deep Cover (1992) takes a different approach from those just mentioned, plunging into genre tropes ranging from film noir to the neon-lit crime chic of Michael Mann’s Miami Vice (1984-1990). Woven through familiar narrative elements, though, is a bitterness and anger which indict the social and political forces which use, abuse and discard People of Colour with chilling callousness. The movie declares its use of noir in a prologue which sets the terms with brutal efficiency. On a snowy Cincinnati street at night, a car pulls up in front of a liquor store. Inside are a young boy named Russell Stevens Jr. (Cory Curtis) and his father Russell Sr. (Glynn Turman), who snorts some coke and angrily tells the boy never to do the same. Then he pulls a pistol from the glove compartment and almost hits the boy when he pleads with his father to stop. Sr. tells him that the only way to get anything in life is to take it and he’s going to take money to buy Russell a Christmas gift.

Inside the store, Russell Sr. shoots the owner and comes back out, holding the money up for his son to see through the window. But this paltry triumph is abruptly cut short as his blood splatters across the window, the wounded owner having emerged and shot him in the back with a shotgun. Russell Sr. dies with his son looking on helplessly as we hear the voice of a grown-up Jr. saying that whatever happened in his life, it was not going to be this. Throughout the film, this voiceover comments on the action and the choices Russell faces; the tone is almost poetic, filled with the pessimistic fatalism of noir.

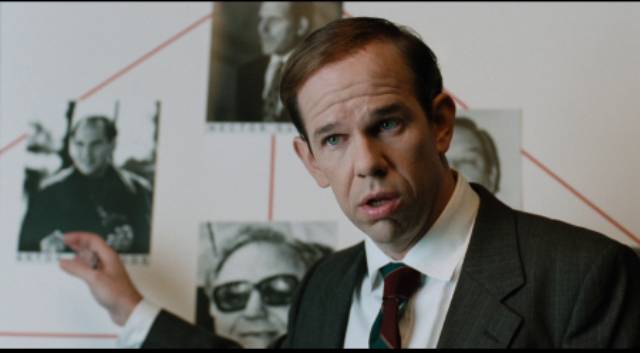

Twenty years later, having done his best to avoid the kind of life which destroyed his father, Russell (now Laurence Fishburne) is a cop in uniform. We meet him as the third policeman interviewed by a smarmy man in an office. This is Carver (Charles Martin Smith), a DEA agent whose interview consists of a single question: “What’s the difference between a Black Man and a n—-r?” The first candidate is awkward and embarrassed, the second grabs Carver and almost drags him across the desk, but the third – Russell – recognizes that there’s no answer which won’t trap him. He’s subtle and self-aware and Carver tells him that everything in his profile fits him for the job he has in mind … that, in fact, Russell would make a perfect criminal. Here Russell is confronted with the power of white society to label and define him no matter how he wants to define himself.

When Carver proposes that he go undercover to infiltrate a West Coast drug operation being fed by a South American cartel, he casts the job as an opportunity to make a difference to “your community”, to save kids destined to be destroyed by drugs and crime. But in order to accomplish this, Russell will have to become the very thing he swore he would never be. Yet he finally agrees and is relocated to Los Angeles with a new identity as small-time drug dealer John Hull. And slowly, methodically he makes himself known and works his way up through the supply chain.

Along the way, he comes to the attention of local kingpin Felix Barbosa (Gregory Sierra) and eventually teams up with Barbosa’s lawyer David Jason (Jeff Goldblum), who has ambitious plans of his own to start a business in designer drugs which will bypass the whole cocaine smuggling operation. What troubles Russell most is just how good he is at working in the drug business. At first, he tries to maintain some distance and retain his identity as a cop … but Carver keeps pushing him deeper, urging him to function as a fully-fledged drug dealer, even when it leads him into necessarily killing a violent rival. The gradual slipping of his real identity into the assumed identity is the central trope of all narratives about undercover cops (Mike Newell’s Donnie Brasco [1997], Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs [1992], William Friedkin’s Cruising [1980])… What happens when the role comes to define the man? What happens when that role is defined by a white establishment and imposed on a Black man determined not to be so defined?

As Russell continues to rise in the organization and, in partnership with Jason, begins to operate within criminal rather than police terms, he takes on new levels of power, eliminating Barbosa and moving even higher as he approaches Hector Guzman (Rene Assa), the head of the cartel who also happens to be a diplomat protected by rules of diplomatic immunity. When Carver abruptly tries to pull him in and end the operation because the State Department now sees Guzman as a political asset, Russell goes it alone … but his motives are confused. As he says to Carver, he used to be a cop pretending to be a criminal, now he’s a criminal pretending to be a cop.

He and Jason follow through with their plans to establish a new business in collaboration with Guzman, but at the crucial moment his real identity asserts itself. In the end, he rejects both sides of the dichotomy he’s been trapped in because both are essentially defined by the dominant culture and neither recognizes a true, self-determined identity. The film ends with Russell poised in ambiguity; he doesn’t yet know what possibilities are available to him, but he does know that he is no longer cop or criminal. The moment is both liberating and vertiginous.

While deftly managing all the elements of what superficially is a familiar story, Bill Duke and his excellent cast manage to explore complex issues of identity with subtlety and intelligence. Fishburne and Goldblum form a fascinating variation on the biracial buddy pairing so often used as an action-comedy staple in the ’80s and ’90s, but with Goldblum’s middle class white lawyer plunging wholeheartedly into criminal activity while Fishburne’s conflicted cop seeks a way out without losing his integrity entirely. Smith, most famously Toad in George Lucas’ American Graffiti (1973), is startlingly good as the weaselly functionary for whom bureaucratic advancement is all that matters and who ultimately has no concern for the damage being done to the community he claimed to want to protect when he recruited Russell.

The most timely aspect of the script, originally written by Michael Tolkin with a white central character and reworked by Henry Bean in collaboration with Duke, was its exposure of the complicity of U.S. government agencies with the drug trade from South America because it was “in the interests” of the U.S. to work with powerful figures who financed their political activities with drug money. Not only did the government facilitate the drug trade to some degree, it then used the domestic drug business as an excuse to excessively police communities of colour, combining corrupt political activities with the devastating “war on drugs” which perpetuated the criminalization of Black men in particular, a kind of win-win for the racism so deeply embedded in American society.

*

The disk

A 4K scan from the original negative gives Bojan Bazelli’s colour-saturated imagery a vibrant neon sheen with a lot of detail in the ubiquitous night scenes. There’s a moody score by Michel Colombier, supplemented with a lot of contemporary tracks in various styles, including the influential title track by Dr. Dre which also introduced Snoop Dogg.

The supplements

Criterion include some excellent extras which provide context for the film as part of the explosion of Black Cinema in the ’90s. New features are an interview with Duke (18:16) which covers his career as both actor and prolific director and the place of this feature in his work; a conversation between film scholars Racquel J. Gates and Michael B. Gillespie (35:37) about the position of Deep Cover in that boom and its relation to film noir; and a discussion between music scholars Claudrena N. Harold and Oliver Wang (17:36) about the significance of the title track to hip-hop and film music. There’s also a post-screening discussion and Q&A from the AFI in 2018 featuring some lively conversation between Duke, Fishburne and moderator Elvis Mitchell (56:33).

There’s a very brief and inadequate trailer (00:44), and the booklet essay is by Gillespie.

Comments