Columbia Noir #3 from Indicator

Indicator’s Columbia Noir #3 box set has arrived just three short months after volume 2, which in turn came out just two-and-a-half months after volume 1 (and they just announced a September release for volume 4!). Despite the speed with which they’ve been putting these sets together, quality remains high, with yet another eclectic selection of B-movies produced by the studio between the late-’40s and late-’50s. Once again, there are early works from major directors at the beginning of their careers and interesting films by mid-tier figures who occasionally rose above the constraints of studio assignments. As with the previous sets, the term film noir is used as a fairly loose catch-all which encompasses almost anything involving crime, not necessarily limited to the moral and existential dread of the category’s greatest exemplars.

Johnny O’Clock (Robert Rossen, 1947)

Robert Rossen was a well-established screenwriter by the time he made his directorial debut with Johnny O’Clock (1947), which he adapted from a story by associate producer Milton Holmes. Perhaps he needed to take this project to prove he could direct, but it doesn’t display the kind of ambition apparent in his subsequent features. Ironically, he followed it immediately in the same year with what might be considered his auteurist debut, Body and Soul, which he didn’t actually write himself (the script was by Abraham Polonsky). There’s a generic quality to Johnny O’Clock, a dependence on convoluted plotting which seems more than a little arbitrary, which prevents the characters from taking on much autonomous dramatic life.

Which is not to say that the cast isn’t very good – though with the casino setting and an ambiguous hero torn between two women, I found myself continually envisioning Bogart in the role of Johnny instead of Dick Powell, who seems a bit lightweight. Our protagonist (whose odd name is commented on but never really explained) runs a casino in partnership with a shady character named Guido Marchettis (Thomas Gomez), who has criminal connections. We’re obviously supposed to identify with Johnny, but the movie remains vague about his own involvement with his partner’s criminal activities. Rick in Casablanca may be shady, but he’s honourable; Johnny is compromised by his partnership with Marchettis.

To make things more complicated, Marchettis’s wife Nelle (Ellen Drew) is still in love with Johnny, though she chose to marry his partner for financial security. The alcoholic Nelle does little to conceal her feelings, repeatedly putting Johnny on the spot. Meanwhile, one of Marchettis’s associates is crooked cop Chuck Blayden (Jim Bannon), who is doing what he can to push Johnny out and take his place in the business. Blayden is a thug, who happens to be involved with hatcheck girl Harriet Hobson (Nina Foch), who wants to end the connection. When she turns up dead, an apparent suicide, her sister Nancy (Evelyn Keyes) arrives in town, and one thing leads to another … police inspector Koch (Lee J. Cobb) determines that Harriet was murdered, Johnny finds himself falling for Nancy, people get shot at, Johnny finally decides to get out of the business … but you know how it is, getting out is not so easy, particularly when a vindictive former lover is involved.

Johnny O’Clock is fairly entertaining, but it never quite rises above its status as a studio B-movie despite the cast, though Rossen keeps things moving and it’s nicely shot by Burnett Guffey.

Sony’s 2K restoration looks very good and, as usual, the disk has interesting extras. There’s a commentary from film historian Jim Hemphill, the Three Stooges short Whoops! I’m an Indian! (1936) and a short called Not One Shall Die (David Lowell Rich, 1957), made for the United Jewish Appeal as part of a fundraising campaign to help refugees from Central Europe. Each set has included one or two documentary shorts about immigrants and refugees, pointing to the unsettled nature of the world these noir movies emerged from.

*

The Dark Past (Rudolph Maté, 1948)

Rudolph Maté’s The Dark Past (1948) combines the obsession 1940s Hollywood had with psychoanalysis with a claustrophobic home invasion story which looks very much like an inspiration for Joseph Hayes’s 1954 play The Desperate Hours, which in turn was the basis for William Wyler’s 1955 movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Frederic March. In Maté’s movie, the roles of a vicious killer and a middle class family man are played respectively by William Holden and Lee J. Cobb, while the hostage situation literally becomes a therapy session.

Based on a play called Blind Alley by James Warwick, previously adapted in 1939 by Charles Vidor and also apparently adapted for television at least four times, The Dark Past mixes crime with a rather blunt social issues drama. It begins with police psychologist Dr. Andrew Collins (Cobb) taking an interest in a juvenile offender and explaining to a cop that what these kids need is understanding and treatment rather than incarceration and punishment. To prove his point, he tells the cop the story of vicious killer Al Walker (Holden).

As a university lecturer in psychology, Collins takes an intense interest in the people he meets. One weekend, he heads for the family cottage at the lake with wife Ruth (Miss Moneypenny herself, Lois Maxwell) and son Bobby (Bobby Hyatt), plus a few friends. At the same time, killer Walker has broken out of prison and is heading to the same lake, where some accomplices are due to pick him, his girlfriend Betty (Nina Foch again) and their gang up by boat. On the way, we see Walker cold-bloodedly kill the warden they had taken hostage. He appears to be irredeemably vicious, so when he decides to hide out at the Collins cabin, nobody is safe.

With the servants tied up in the cellar and the family and guests being watched by the gang up in the bedrooms, Collins and Walker begin to lock horns downstairs. Walker is jumpy, Collins is cool. And Collins’s close observation, putting the killer under a metaphorical microscope, just makes the criminal even jumpier. Yet he can’t help himself starting to ask questions about the doc’s work and the books on insanity he sees on the desk and in the bookcase. It soon becomes clear that Walker has some self-awareness about his own damaged psyche and that creates an opening for Collins.

When the killer slips into an uneasy sleep, Betty tells the doc that her boyfriend has been plagued for years by a recurring dream. Another opening. When Walker wakes, Collins begins to probe and we get one of those long Hollywood analytical sequences – think Ingrid Bergman, Gregory Peck and Salvador Dali in Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) – and an analysis of the dream’s symbols quickly reveals its meaning in a surprisingly literal and prosaic way … it’s all about a cruel dad and a mom the boy may have had problematic feelings about. Yep, Oedipus rears his head and Walker, having reached clarity, loses his anger and the instinctive violence with which he has always lashed out at the world. When the cops finally show up at the cabin, the fight has gone out of him…

In a coda back at the police office the skeptical cop has been convinced that the juvenile offender he arrested needs understanding rather than a punishment which could easily turn him into another Al Walker.

The Dark Past remains rather stage-bound and a lesser cast probably couldn’t have overcome the script’s creaky mechanics. But Holden and Cobb are well-matched as the antagonists, while Foch provides strong support in a fairly nuanced role as a woman who has tried deliberately to make herself hard in order to fit in with the man she loves. Director Rudolph Maté had a long and distinguished career as a cinematographer before turning to directing when he was almost fifty – among other credits, he shot The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Vampyr (1932) for Dreyer, Foreign Correspondent (1940) for Hitchcock, To Be or Not to Be (1942) for Lubitsch, and also did some uncredited work on The Lady from Shanghai (1947) for Welles. His directing career was less notable, though D.O.A. (1949) is a terrific little noir and When Worlds Collide (1951) is a key ’50s sci-fi movie.

Like the other films in the set, The Dark Past has excellent image quality. The commentary is by academic Eloise Ross and there’s a discussion of Nina Foch’s career by Pamela Hutchinson. There’s a radio adaptation of the play starring Edward G. Robinson and as always a Three Stooges short, Shivering Sherlocks (1948).

*

Convicted (Henry Levin, 1950)

Henry Levin was also a prolific though undistinguished director, moving up from B-movies in the ’40s and ’50s to occasional bigger productions like Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962, co-directed with producer George Pal) and Genghis Khan (1965). Convicted (1950), a taut prison picture, is a far cry from those colourful fantasies.

Like The Dark Past, Convicted was based on a play which had already been adapted several times, most notably as The Criminal Code (1930) by Howard Hawks. In classic prison movie form, it deals with a nice guy being sent to the pen for the first time and having to find a way to survive. The ambiguous original title refers both to the laws which condemned him and to the rules by which the prisoners live, rules which reflect a twisted mirror morality which mocks the society which put these men away.

In this particular case, Joe Hufford (Glenn Ford) is not an innocent man, but neither is he a bad man. He got into a drunken argument in a nightclub and hit a man who was insulting the woman he was with … and the man cracked his skull when he fell. The prosecutor likes Joe and understands that it was accidental, but the law is the law and he has to lay charges. In fact, both the prosecutor and the judge bend over backwards to make things easy on Joe. Unfortunately, the lawyer provided by his employer has no experience with criminal law – he’s a business attorney – and his ego makes him reject every break that’s thrown his way. He blows the defence and the judge must sentence Joe to a long term behind bars.

Joe is a decent guy trapped by circumstances. He didn’t act deliberately, but accepts the consequences. Years into his sentence, a new warden takes over the prison – having lost an election, the D.A. who prosecuted him arrives to take over the brutal institution, many of whose inmates he sent there. George Knowland (Broderick Crawford) is a decent man himself who has devoted his life to the law; now he gets a close-up view of the consequences of his own actions, among them what has happened to a man he didn’t think belonged in prison but whom he got convicted anyway.

Knowland tries to ameliorate the situation, assigning Joe to be his own driver whose duties include driving Knowland’s daughter Kay (Dorothy Malone) into town to do her shopping. His new role begins to lift the weight of imprisonment from Joe, but Knowland’s efforts to get him paroled are thwarted because the father of the man he killed is rich and powerful and the parole board is unwilling to risk his ire.

Still trapped by the workings of a system which is somewhat removed from actual justice, Joe faces more difficulties when a stoolie informs on an escape attempt, leading to the deaths of several prisoners. That stoolie, Ponti (Frank Faylen), is targeted for retribution and ends up dead in the warden’s office, with Joe the only potential witness. He has a choice: inform on the man who killed Ponti or lose his chance at parole. Knowland argues for the rules of the Criminal Code, while Joe is now bound by the code which governs the men among whom he lives in the prison. His refusal to inform cements the respect of the prisoners and the man who actually killed Ponti ultimately sacrifices himself for Joe.

The script by William Bowers with Fred Niblo Jr and Seton J. Miller (who wrote the Hawks version) provides a collection of engaging characters who are morally flawed but only in a couple of cases deliberately do bad things – Faylen’s Ponti and Carl Benton Reid’s malevolent head guard Captain Douglas are not motivated by honour. Perhaps the biggest difference between this and Hawks’s movie is the fact that while the protagonist of The Criminal Code is young and naive, Joe is older and experienced the war, leaving him with no faith in the fairness of life. Ford, Crawford and Malone are strong leads, and Millard Mitchell is a standout as a bitter long-term prisoner (the role played by Boris Karloff in the earlier adaptation). And once again Burnett Guffey provides excellent, atmospheric cinematography.

No need to comment again on the excellent image quality. Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson provide the commentary, and there’s a long video essay by Jonathan Bygraves comparing Convicted to the Hawks film and John Brahm’s Penitentiary (1938), also adapted from the play. The Three Stooges short is So Long Mr. Chumps (1941).

*

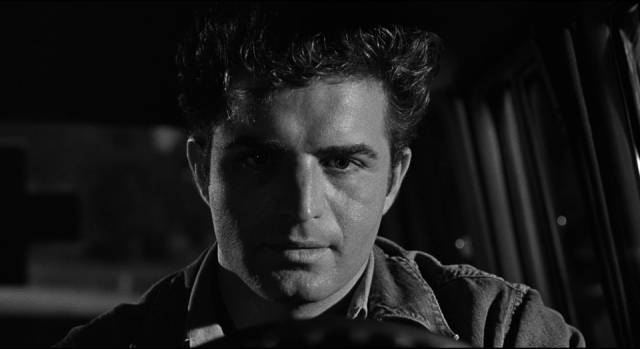

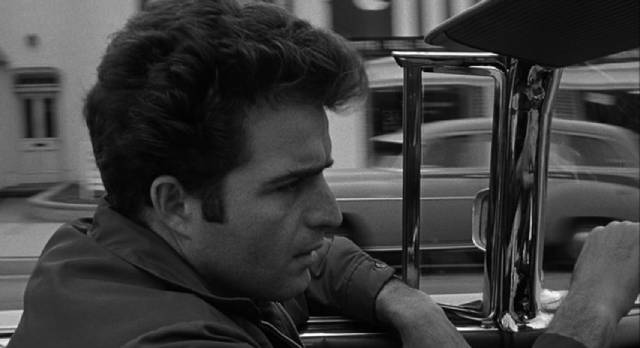

in Gordon Douglas’s Between Midnight and Dawn (1950)

Between Midnight and Dawn (Gordon Douglas, 1950)

Noir virtually by definition deals with outsiders, criminals or good people who find themselves on the wrong side of the law due to circumstances beyond their control. So does a movie about a couple of patrol car cops on the job really count? Although one of the cops in Gordon Douglas’s Between Midnight and Dawn (1950) does push against the rules in his pursuit of a racketeer, cynically dismissing anyone who comes to the attention of the law as lowlife scum, these two buddies are not compromised the way a typical noir (anti-)hero is.

We meet them on night duty, with cynical Dan Purvis (Edmond O’Brien) showing the less-experienced Rocky Barnes (Mark Stevens) the ropes. Rocky takes a more sympathetic view of human beings and is sometimes shocked by Dan’s harsh treatment of the people they encounter on the job. But Dan’s attitude makes him more observant and knowledgeable about criminals, so when they stop at a nightclub run by Ritchie Garris (Donald Buka) he recognizes a mob big shot from back East at a nearby table and realizes something bad is in the works; reporting to his superiors, he triggers an investigation which will later have serious consequences.

Alongside the police procedural narrative, there’s also a romantic thread as Rocky becomes interested in the voice of a new dispatcher. Dan warns him that such impressions are deceptive, but they eventually discover that the voice belongs to Kate Mallory (Gale Storm), who turns out to be attractive and also their Lieutenant’s new secretary. They both hit on her, but while she seems amused she also asserts that she won’t get involved with a cop because her father, who was on the force, was killed on duty. That doesn’t discourage Rocky and Dan, though. They begin to compete for her attention when off duty, while pursuing Garris when they’re at work.

The crime part of the story is pretty straightforward; the romance, however, is strange. The two men rent an apartment together from Kate’s mother and move in next door, making themselves rather obnoxiously intrusive. Kate is not pleased, but her mother encourages the two guys. Eventually Kate is worn down and falls for Rocky, her choice adding to Dan’s cynicism and driving him to become more aggressive (and transgressive) in his pursuit of Garris.

Apart from the odd romantic triangle, the most implausible element of Eugene Ling’s script is the way Lieutenant Masterson (Anthony Ross) starts bringing his secretary Kate into dangerous situations involving Rocky and Dan. All pretense of realism goes out the window in order to ramp up the dramatic stress she feels now that she’s involved with a cop. The movie’s most unexpected surprise comes just before the couple are due to get married … a development which confirmed my impression that Between Midnight and Dawn was a seemingly more than coincidental precursor to The New Centurions (1972), Richard Fleischer’s adaptation of Joseph Wambaugh’s novel. Wambaugh makes the older cop (George C. Scott) more sympathetic, but he’s there to teach the younger man (Stacey Keach) the ropes and introduce him to the seedy underside of society. The younger cop’s sympathy for people becomes strained the more he sees … and he, like Rocky, pays a steep price for not becoming hard enough.

Strangely, by the end Dan learns that his view of the world is too harsh, that the “scum” are just people too, who have good points along with the bad.

Gordon Douglas was the epitome of a journeyman filmmaker, his long career encompassing a wildly diverse range of material – comedies, mysteries, westerns, B-movies and A-features, the ’50s giant ant favourite Them! (1954), eventually leading to an association with Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack in the ’60s. Along with Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), he directed Sinatra’s two Tony Rome thrillers plus one of star’s most interesting movies, The Detective (1968). But Douglas didn’t have a particularly discernible personality – a tough guy, something like a bargain Robert Aldrich without the intensity. He’s not quite able to pull together all the disparate elements of Ling’s Between Midnight and Dawn script, the awkward comedic moments jarring against the toughness of the crime story, with the romance shoehorned in and repeatedly getting in the way of the action.

The fine transfer is supplemented with a commentary by author Bryan Reesman and an interview with Kim Newman about Douglas’s career. The Stooges show up in Dizzy Detectives (1943).

*

The Sniper (Edward Dmytryk, 1952)

Like the final films in the two preceding sets – Don Siegel’s The Lineup (1958) and Irving Lerner’s Murder By Contract (also 1958) – the last two movies in the set belong to a distinctly different age. If the post-war noirs existed in the shadow of German Expressionism, using that style as a way to evoke the moral confusions wrought by the horrors of global violence, during the 1950s popular culture was infused with the paranoia of the Cold War and the increasingly entrenched ideological divide between Right and Left. Director Edward Dmytryk was himself caught up in that matrix, having at first refused to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and being sentenced to prison as one of the Hollywood Ten. Like others, he fled to England where he made a couple of movies, but unlike Joseph Losey and Cy Endfield he decided to return to the States and was briefly locked up before changing his mind and naming names in 1951. Ironically, one of the first producers to hire him after this was prominent liberal Stanley Kramer.

It’s interesting to see Kramer’s production The Sniper (1952) in this set alongside The Dark Past. Both movies centre on a psychologically disturbed killer and feature a police psychologist working to understand what’s behind the violence. The big difference is that the earlier film believed that Freudian analysis could unearth the truth and “cure” the killer, while in The Sniper motive remains to some degree inexplicable, implying that such crimes might erupt anywhere at any time, undermining any sense of security people might feel as they went about their daily business.

Edward Miller (Arthur Franz) is a delivery man, picking up and dropping off laundry for customers of a cleaning company. He’s tormented by sexual feelings for women he encounters on the job and his own inability to act on those feelings. Watching couples walking on the street below his window, his resentment rises to unbearable levels. He keeps an M1 rifle in his dresser drawer, a souvenir from his wartime service, and takes it out to aim at the women below. And yet he knows he’s sick and for a while resists his urges.

That is, he resists until he can’t. One of his customers is Jean Darr (Marie Windsor), a nightclub piano-player, who greets him only partially dressed, offering him a beer. This seems too good to be true, and it is – she has to hustle him out the back door when her boyfriend arrives. That night, Miller follows her to her club and waits on a roof opposite with his rifle. When she leaves work, he shoots her.

Appalled by his own act, he sends a note to the police pleading with them to stop him before he kills again. (A similar message was left at a murder scene in 1945, attributed to William Heirens, whose eventual confession had been obtained by literal torture.) Having killed once, Miller’s self-control collapses and the police are faced with a serial killer. While politicians and business leaders apply pressure, Lieutenant Frank Kafka (Adolphe Menjou) works with psychologist Dr. James Kent (Richard Kiley) to create a profile which might lead them to the killer.

Harry Brown’s script (from a story by Edna and Edward Anhalt, who had just provided the story for Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets, and would later script Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler) uses a methodical parallel structure to depict Miller’s crimes and the police investigation slowly closing in on him. Dmytryk uses a flat documentary-like style (shot once again by Burnett Guffey) which resists narratizing Miller’s psychological obsessions, transforming him into an inexplicable modern monster, an embodiment of forces which social institutions are barely, if at all, capable of containing. (He might be seen as a model for Charles Whitman, the 1966 Austin mass murderer, and is an obvious precursor to the killer in Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets [1968].)

The film’s chilling detachment reaches its climax in a sequence in which Miller aims his gun down into a street from a rooftop, trying to decide on a target, only to be spotted by a man working high above on an industrial chimney. The man starts yelling a warning and Miller turns, distressed, and aims at the distant figure. With Miller in the foreground and the worker exposed far in the background, death is inescapable. Dmytryk holds the shot as Miller fires and the man collapses limply on his rope, then begins to slide down the chimney. The lack of stylistic inflection, the cold matter-of-factness of this moment of death, presages the feeling of hopelessness which suffuses the Cold War thrillers to come in which the omnipresent threat of nuclear annihilation hangs over the world.

Burnett Guffey’s cinematography deliberately avoids the Expressionist touches of classical noir, giving The Sniper a generally flat, almost mundane look which serves as counterpoint to the horror it depicts. The commentary from noir expert Eddie Muller and a brief introduction by Martin Scorsese are carried over from Sony’s 2009 DVD edition. The disk includes another United Jewish Appeal short, Three Lives (1953), written by Edna and Edward Anhalt, directed by Dmytryk and starring Arthur Franz. The Stooges short is Three Pests in a Mess (1945).

*

City of Fear (Irving Lerner, 1959)

Nuclear annihilation is an explicit rather than metaphorical threat in City of Fear (1959), Irving Lerner’s follow-up to the excellent Murder By Contract (1958). That film’s star, Vince Edwards, turns up here as Vince Ryker, a con who has just broken out of San Quentin. During the break, he managed to grab a metal cylinder which he thinks is full of heroin; believing he can sell it for an implausible million bucks (it’s only the size of a large soup can), he heads for Los Angeles hoping to make enough money to flee for good. Trouble is, the can is actually full of granular Cobalt-60, a deadly isotope whose radiation is not contained by the steel casing.

As Ryker hides out and tries to make connections, he’s slowly succumbing to radiation poisoning while leaving a trail of dangerous contamination around the city. If he manages to crack the container open (which he repeatedly attempts) and releases the contents, millions could die. Knowing he possesses the container, police and scientists follow his trail. Essentially a time-sensitive chase, City of Fear is not as interesting as Murder By Contract, and despite a relatively brief running time it feels repetitive. But there are effective sequences and the apocalyptic threat does sustain a degree of tension. (One odd thing: IMDb lists a running time of 81 minutes, with a 75-minute running time attributed to a German release. Indicator’s Blu-ray, like the earlier Sony DVD has the 75-minute version, with no indication that there’s a longer cut out there somewhere.)

This was actually the film I was most looking forward to in the set, and perhaps that’s why I was left feeling rather disappointed. Unlike his quirky and enigmatic hit man in the previous movie, Vince Edwards comes off as kind of dumb here, ignoring his own increasing sickness as he keeps trying unsuccessfully to open the canister. It’s hard to believe that a hardened criminal, quite capable of murder, would believe that heroin would’ve been kept in the prison in an apparently impenetrable container, so the plot-driving McGuffin doesn’t make a lot of sense. This technical detail diminishes the suspense of what is essentially a variation on Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950), which had its petty criminal unknowingly infected with pneumonic plague.

Like The Sniper, City of Fear was shot in a flat, documentary-like style – this time by Lucien Ballard – with a degree of immediacy no doubt attributable to a seven-day shooting schedule. The transfer is, of course, excellent. There is a commentary by film critic Adrian Martin, plus some brief comments on noir by Christopher Nolan. In addition, there are three short films produced by Lerner, one of which he also directed; the latter is The Autobiography of a “Jeep” (1943) which introduces the Army’s then-new utility vehicle with a comic tone. This gets a commentary by film historian Jeremy Arnold. The other two shorts are Alexander Hammid’s Hymn of the Nations (1944), in which Arturo Toscanini conducts a musical montage which encompasses the spirit of the Allies fighting against Germany and Japan, and The Cummington Story (1945) about refugees overcoming hostility and resistance in a small American town. And naturally the Three Stooges are here in Oil’s Well That Ends Well (1958).

*

I enjoyed all the movies in this set, as in the two previous sets. Indicator has lavished the same kind of attention on them, with commentaries, featurettes, visual essays and numerous short films. Once again, this wealth of material gives the set interest beyond the intrinsic value of the six features themselves, evoking the social, political and pop culture context within which the films were made.

Comments