Karloff at Columbia on Eureka Blu-ray

It’s one of the paradoxes of cinema history that what were once just disposable filler for theatre programs have in time come to be treasured artifacts. Studios filled their production schedules with various tiers, from prestigious A-features which aimed at box office success, to mid-range supporting features and on down to cheap B-movies rooted in genre conventions, whose chief purpose beyond maintaining a degree of cash flow was to keep contract players and crew people busy while also training new hires. The irony is that, with the passage of time, many of those prestige productions have vanished while these throwaway movies continue to entertain and even offer some insight into the time when they were made. Unlike a lot of later independent productions which might be hampered by a lack of resources, these studio Bs drew on the full technical and talent arsenal available on studio lots; however unambitious such movies might have been, they were created with a high level of craft.

Eureka recently followed their Blu-ray set of Inner Sanctum mysteries with a two-disk set of the six movies Boris Karloff made at Columbia between 1935 and 1942. This includes what is known as the Mad Doctor cycle, bracketed by a Gothic horror and a final film parodying the Mad Doctor movies. All run barely more than an hour, most rely on similar plot devices and characters, they’re all well-crafted – in a couple of cases even better than that – and all showcase just why Karloff had such a long career and garnered such a large and faithful fan base. And all, by and large, were either barely noticed by critics when they were released, or outright dismissed, because few took such small commercial projects seriously.

*

The Black Room (Roy William Neill, 1935)

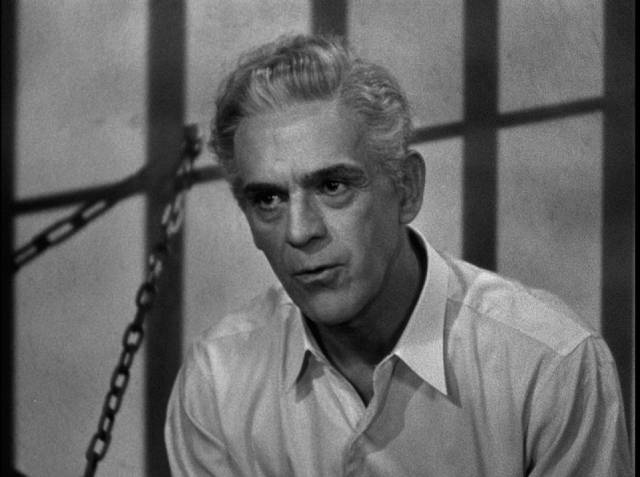

The first film in the set, Roy William Neill’s The Black Room (1935), is a period story about a cursed noble family. Making full use of standing sets on the lot which had been built for much bigger productions, Neill, along with designer Stephen Goosson and cinematographer Allan G. Siegler, creates an atmospheric Gothic tragedy in which Karloff, free of monster make-up, does some of his best work as a pair of twins – naturally, one is decent, the other irredeemably evil. At the moment of their birth, their father declares the family’s doom based on a legend that the line will end when the younger kills the elder in “the black room”, which appears to be the family torture chamber.

Anton, the younger, leaves home, while Gregor inherits the estate on their father’s death and proceeds to give free rein to his sadism and debauchery, which includes raping and murdering local girls. The population grows rebellious, occasionally making attempts on his life, but he won’t change his ways. He even sets his sights on marrying the daughter of local landowner Colonel Paul Hassel (Thurston Hall), much to the disgust of her fiance Lt. Albert Lussan (Robert Allan). As things approach a boil, Anton returns after ten years away enjoying himself in the city. At first, decent as he is, he refuses to believe ill of his brother. For this, he pays dearly, because Gregor publicly relinquishes his title and promises to move away permanently only to kill Anton in the black room (seemingly turning the curse on its head) and assuming Anton’s identity so that he can retain his power and, being the “nice one”, have Thea Hassel (Marian Marsh) as his bride after framing Lussan for the murder of her father.

The switch in identity depends on one key detail: Anton was born with a crippled right arm and Gregor must now and at all times keep that arm twisted against his chest. It’s only a question of how and when he will be forced to use the arm and expose himself – in the event ironically fulfilling the family curse as predicted years before by his father.

Most of the performances are functional, with Marsh merely a pretty object of desire and Allan a dull hero prone to inappropriate, self-defeating bursts of anger. Katherine DeMille, Cecil B.’s adopted daughter, has real presence as a village woman who willingly becomes involved with Gregor but unfortunately takes too much for granted. But the film is a real showcase for Karloff, who not only gets to play two very different brothers, plus the layered role of sinister Gregor pretending to be the gentle Anton – he gets to play both against one another in the same frame. It’s a tour de force displaying the actor’s facility with both menace and charm.

*

The Mad Doctor Cycle (1939-42)

Although the demands of the subsequent movies in the set are more limited, Karloff nonetheless gets to display his familiar screen persona with some nuance as a variety of scientists – not so much “mad” as driven, even obsessed, pursuing their researches no matter what the cost, though always with that classic justification that the potential benefits justify any means. In almost every case, the scientist is about to prove his theory about prolonging life or reviving the dead when hidebound authorities step in and cause disaster, for which they naturally blame the doctor because his ideas go against both human and God’s laws. The first three were all directed by Nick Grinde, whose prolific career lasted from 1928 to 1945; I don’t think I’ve seen any of his other movies, though a couple of titles sound familiar – Million Dollar Legs with Betty Grable and Donald O’Connor and Scandal Sheet (both 1939).

The Man They Could Not Hang (Nick Grinde, 1939)

In The Man They Could Not Hang (1939), Karloff is Dr. Savaard, who has developed an artificial heart which could revolutionize surgery; by freezing the patient, essentially putting them into suspended animation, doctors will be able to take their time to effect repairs and then reawaken the patient with the help of the new pump. A student named Bob Roberts (Stanley Brown) enthusiastically volunteers for the procedure but Savaard’s nurse and Bob’s girlfriend (Ann Doran) is horrified and runs to the police to say that the doc is murdering his assistant. The cops arrive and interrupt and, despite Savaard begging them to give him time to revive Bob, haul him off to jail and send the poor assistant to the morgue for an autopsy.

At his sentencing for murder, Savaard makes an impassioned speech about how hanging him is going to set medical science back for years and condemn to death many who might otherwise be saved, not inaccurately pointing out that it was his nurse who killed Bob rather than himself. Savaard arranges for his body to go to his assistant Dr. Lang (Byron Foulger) after the execution and Lang uses the artificial heart to revive him after surgically repairing his broken neck. Embittered by the whole experience, Savaard abandons his plans for medical miracles and embarks on a campaign of revenge, killing six of the jurors by hanging and then gathering the rest of them – the judge, the police doctor and the nurse – in his mansion, revealing himself to prove the efficacy of his technique and then starting to kill them off one by one.

Traditionally, it’s often unclear what the benefits of a mad scientist’s research might be – apart from proving that he can do it, what actual use is Frankenstein’s piecing together of body parts? But in each of these Karloff movies it’s made clear that his work will have genuine benefits, while the authorities, both civil and medical, repeatedly state that it’s obvious what he’s doing can’t work because it’s never been done before. This blinkered stupidity keeps pushing Karloff’s characters over the edge of acceptable behaviour.

*

in Nick Grinde’s The Man with Nine Lives (1940)

The Man with Nine Lives (Nick Grinde, 1940)

Repetition really kicks in with The Man with Nine Lives (1940), which like the previous movie was scripted by Karl Brown, with Dr. Mason (Roger Pryor) using cryotherapy to cure cancer, once again freezing a living body in order to repair damage caused by the disease. Following a demonstration, the press are ready to proclaim a miracle cure but Mason insists more research is needed. His bosses at the hospital are annoyed by the publicity and force him to take leave until the fuss dies down. So he takes the opportunity to go in search of Dr. Leon Kravaal, a pioneer in cryotherapy who vanished ten years earlier.

Travelling to a remote area with his nurse, Judith Blair (Jo Ann Sayers), he heads for an island which belonged to Kravaal, despite warnings from superstitious locals who remember that the doc vanished along with the sheriff and other local officials and the nephew of Kravaal’s patient, who was mostly concerned about his inheritance. When Mason and Blair discover a lab deep beneath the house, they also discover, first, the skeletal remains of the patient, and then Kravaal and the others frozen in ice, perfectly preserved and still alive. Revived, Kravaal points out that, once again, these people who interfered with his work were directly responsible for the death of his patient. As they still scoff at his claims, Mason defends him, pointing to medical progress since they were frozen ten years earlier. Kravaal, determined to continue his work, imprisons everyone, but needless to say these are not ideal circumstances and chaos ensues with a bunch of people ending up dead. If only people would just step aside and let geniuses get on with their work!

*

Before I Hang (Nick Grinde, 1940)

Although cryogenics don’t play a part in Before I Hang (1940), the third movie in the series, there is a serum which may well reverse the aging process. Unfortunately this is the discovery of kindly Dr. John Garth, who has committed the unforgivable sin of helping a terminally ill patient who could no longer endure years if excruciating pain die a peaceful death. Under the law, despite his benevolent motives, this is considered murder and Garth is sentenced to hang.

With just a month to go, the prison doctor persuades the warden to allow Garth to continue his researches into the serum in the hospital infirmary. On such a tight deadline, the doctors take some shortcuts, using blood from a recently executed murderer to produce the serum and then testing it on Garth himself shortly before his own execution. But then there’s a last-minute commutation to a life sentence and it becomes apparent that Garth is actually growing younger. This discovery earns him a reprieve and he’s continuing his researches as a free man when he unfortunately discovers that he’s been contaminated by the murderer’s blood and during occasional blackouts he starts strangling people…

All three of these movies are quite threadbare and Grinde doesn’t have Neill’s stylistic flair. Although the “science” is generally nonsense (covering a body with ice cubes destroys cancerous tumours?), it’s interesting that whether by design or not things go wrong because of the actions of conservative, reactionary authorities who simply can’t see or accept the radical advances being made by innovative scientists. It’s easy to dismiss the details with mockery, but these breezy B-movies are entertaining and Karloff always treats his roles without contempt. He was a real pro who did his best whatever the circumstances and manages almost single-handedly to underscore even the sillier elements with gravitas.

*

in Lew Landers’ The Boogie Man Will Get You (1942)

The Boogie Man Will Get You (Lew Landers, 1942)

All of this is deliberately mocked in Karloff’s final movie for Columbia, Lew Landers’ The Boogie Man Will Get You (1942). As Professor Nathaniel Billings, he plays an absent-minded scientist living in a rundown colonial-era inn and conducting experiments in the basement with a machine he believes will transform ordinary people into supermen to help the war effort. His subjects are the occasional door-to-door salesmen who come knocking. His failures are kept in a secret room behind the cobwebby wine racks. There’s an eccentric couple maintaining the place, housekeeper Amelia (Maude Eburne) and gardener-handyman Ebenezer (George McKay), and looming over it all a shady creditor who holds the mortgage.

The latter is Dr. Arthur Lorentz, the local coroner, sheriff, justice of the peace, loan shark and swindler, played with energetic glee by Peter Lorre in his first pairing with Karloff … and frankly he pretty much walks off with the movie. Setting things in motion is the arrival of Winnie Slade (Jeff Donnell), who makes an offer on the property, closing the deal by buying the mortgage from Lorentz with cash on condition that she allow Billings to continue his experiments in the lab downstairs. What follows is a more or less random series of arrivals and departures, misunderstandings, revivals of the apparently dead, and the appearance of a Fascist saboteur … all eventually tied up neatly.

With the change in tone and all the farcical busy-ness, Karloff more or less disappears into the scenery. Although a wry sense of self-awareness runs through his career, he seldom appeared in outright comedies and when he did, he tended to be overshadowed by co-stars like Lorre or Vincent Price, who were more comfortable playing broadly (as in Jacques Tourneur’s The Comedy of Terrors and Roger Corman’s The Raven [both 1963]). The Boogie Man Will Get You is more likely to be enjoyed by those who find the preceding Mad Doctor movies risible.

*

in Edward Dmytryk’s The Devil Commands (1941)

The Devil Commands (Edward Dmytryk, 1941)

I skipped over the fourth of the “mad doctor” movies because it stands somewhat apart from the others and, along with The Black Room, is the highlight of the set. Although produced on the same level as the others, The Devil Commands (1941) is noticeably different in tone, darker and grimmer. This is due to a couple of things, not least the replacement of Nick Grinde by Edward Dmytryk, still early in his career and several years away from what was probably his breakthrough, the Raymond Chandler adaptation Murder, My Sweet (1944). While Grinde’s work is visually somewhat flat, Dmytryk infuses his film with gloomy Gothic atmosphere which goes a long way to making up for the shortcomings of the script by Robert Hardy Andrews and Milton Gunzburg.

The other thing that draws me to this movie is the fact that the script was based on one of my favourite horror novels. William Sloane only wrote two novels, but both are genre classics. Although the first, To Walk the Night (1937), is generally regarded more highly, I prefer its follow-up, The Edge of Running Water (1939), which I bought in 1967 when it was reprinted by Bantam. It evokes the same kind of cosmic dread that H.P. Lovecraft aimed for, but the quality of Sloane’s writing was less overwrought, more literary. I loved the book so much that way back when I had big dreams I imagined one day adapting it into a movie. That obviously never happened, but I look back fondly on my naive younger self.

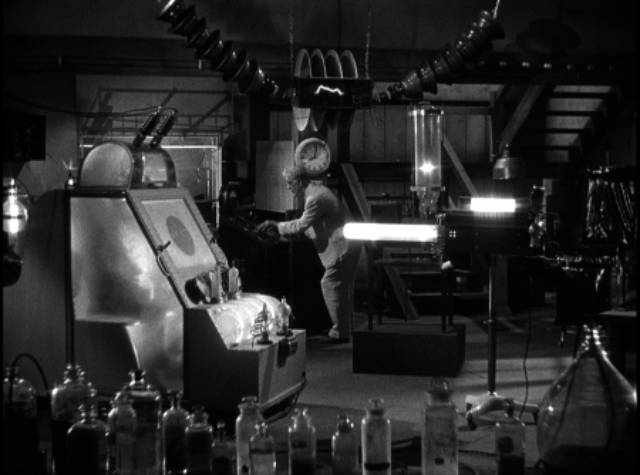

It was several years later that I learned that there had actually been an adaptation, a movie made just a couple of years after publication, when I read the surprisingly favourable entry on the movie in William K. Everson’s Classics of the Horror Film (1974), which was accompanied by an enticing still showing the lab with its ominous “high tech” seance set-up. It was decades later before I finally had a chance to see the film; Columbia released it on DVD in 2003. As always in such situations, all those years of anticipation complicated the experience, but despite its deficiencies as an adaptation of a brilliant novel, Dmytryk’s movie had – and still has – its own satisfactions.

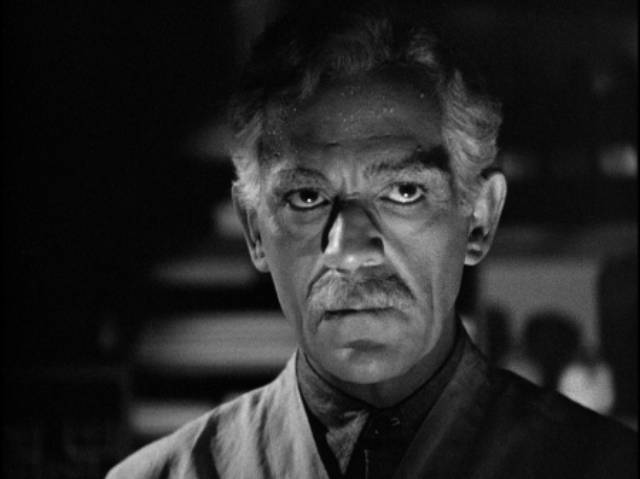

In The Devil Commands, Karloff plays Dr. Julian Blair, a researcher who is developing a machine which can read the electrical impulses of the brain and convert them into a graphic representation which he believes he will eventually be able to interpret as thoughts. (You have to be lenient here as his machine is essentially an electroencephalograph, which had actually existed for years, having first recorded human brain activity in 1924.) Blair is a pleasant man with a positive outlook … until his beloved wife is suddenly killed in a car accident. After the funeral, he retreats to his lab and while fiddling with his machine it produces a trace identical to his wife’s brainwaves.

Excited, he calls in his colleagues – and his daughter – to show them, arguing that this is proof of survival after death. He quickly realizes that they think he’s delusional, a victim of wishful thinking. The only person not humouring him with humiliating condescension is Karl (Ralph Penney), the custodian, who tells him about his own experiences contacting his dead mother with the help of medium Blanche Walters (Anne Revere). Although skeptical, Blair goes along with Karl and although he easily exposes Mrs. Walters cheap tricks, he nonetheless senses something powerful during the seance. He invites her back to the lab and demonstrates her ability to generate and withstand a powerful electrical charge. Connected to his machine, she serves as a booster and once again he seems to contact his wife’s consciousness. Adding Karl to the mix, he seems to hear his wife’s voice, but the huge charge fries Karl’s brain.

Realizing the financial potential of his work, Mrs. Walters persuades Blair to pack up his equipment (and the now mute Karl) and move to a remote location to continue his research. Here, about half way through, we get to the beginning of the novel, everything we’ve seen being backstory laid out chronologically. The tone now changes, becoming a mixture of Gothic horror and science fiction, with Blair so consumed by his desire to contact his wife that he doesn’t realize just how much Mrs. Walters is now controlling his life. He’s an emotional wreck and when the local sheriff comes by to ask questions about some bodies which have disappeared from the graveyard, it’s the medium who sends him packing.

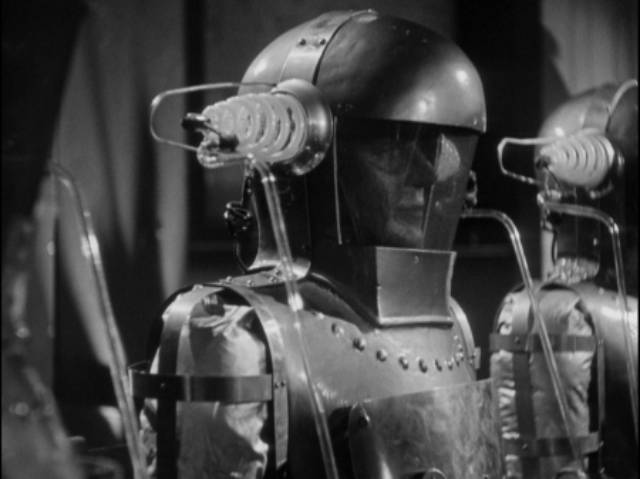

The bodies are actually in the lab, inside strange diving suits arranged around a table in a parody of a traditional seance, hooked together like a series of linked batteries which amplify Mrs. Walters’ powers, creating a kind of vortex which Blair believes is an opening to the afterlife. When the housekeeper, Mrs. Marcy (Dorothy Adams), sneaks into the lab at the sheriff’s request, she inadvertently knocks the power switch and is killed when the vortex drags her across the room. Although Mrs. Walters makes it appear that Mrs. Marcy fell from the cliff as she walked home, the local townsfolk have had enough and head for Blair’s house with what amounts to pitchforks.

Given the brief running time, it’s not surprising that the final act is rushed and there seem to be crucial narrative elements missing, and the low budget makes the ending perfunctory – how does Blair convince his daughter, who has suddenly arrived at the sheriff’s invitation, to take Mrs. Walters’ place in the control unit? This crucial conversation is missing. And the final rush obscures what may be the most interesting narrative element.

Blair has been convinced since that first intimation of survival that he is coming close to communication with the dead, proving conclusively that there is an afterlife. But is that just wishful thinking on his part? It seems as likely – perhaps more likely – that his machine is opening a portal to some other dimension which represents a kind of Lovecraftian cosmic horror, that whatever that voice he hears might be it’s certainly not his beloved wife, but rather something using him to get access to our world.

Whatever it is, there is no sense of comfort or consolation in the lab, but rather something dark and frightening. Given the implications of the story and the absence of some conventional religious explanation for what’s going on, it seems surprising that the movie didn’t raise any flags for the Production Code office. Science might be interfering with things better left alone, but there’s no countervailing orthodoxy to offset the air of horror.

Karloff is as good as ever in conveying the two stages of Blair’s fractured life, the cheerful optimist of the opening scenes and the victim of crushing grief who takes part in increasingly dubious activities under pressure from Mrs. Walters. But the film surprisingly belongs to Anne Revere, who is magnificently sinister and manipulative as a con artist who seizes the opportunity to control and exploit a brilliant man who is succumbing to his own weakness and delusion.

Although there are a few signs of print damage and compromised sources, for the most part the transfers look excellent, with fine detail and an authentic film-grain texture. Each film gets a commentary track (so far I’ve only listened to the lively and appreciative comments by Stephen Jones and Kim Newman on The Devil Commands) and each disk has two old radio half-hours starring Karloff. There are also still galleries and a fairly substantial booklet with essays and excerpts from books about the star.

Comments