Vinegar Syndrome summer binge, part one

in Anson Williams’ All-American Murder (1991)

My disk buying has evolved quickly over the past year. It used to be a matter of browsing in a local store (there’s really only one left within easy reach of where I live) or glancing at on-line review sites for suggestions. There were a few websites I would check regularly for new releases – Criterion, the BFI, Arrow – and that would keep me busy. Then a couple of years ago, I began to visit other sites more often – Indicator, Severin, and then a bit later Vinegar Syndrome – looking through their back catalogues and placing occasional orders. But with the lockdown starting in March of last year, the visits to local stores became virtually non-existent and the on-line shopping became increasingly compulsive. With the back catalogues ransacked, monthly announcements of new releases became significant events – I began placing more and more pre-orders, sometimes several months ahead.

And then there were the bundles. These, a simple marketing technique, quickly got their claws in me. A lot of these companies, announcing three or four new titles per month, offered a discount if you ordered everything. And sometimes, they’d sweeten the offer with bonus swag – t-shirts, pins, figurines, comics based on the new releases. If there were four new titles and three interested me, I’d order the bundle and take the extra, less-interesting one as well, even though the discount didn’t really amount to much of a saving. Over the past year I’ve become much more of a well-trained consumer! And my collection has swelled accordingly with the inclusion of disks I wouldn’t normally have bought and which perhaps a little too often have proved disappointing. A growing awareness of the percentage of dross arriving in the mail may be provoking a bit of a backlash which will finally start reining in my knee-jerk “order everything” behaviour.

Vinegar Syndrome had a big sale in May with a bundle including three box sets and a couple of fancy special editions; I pre-ordered that in March even though two of the releases weren’t actually identified until the sale. I even added six catalogue titles to that order, eventually receiving a big box stuffed full of exploitation gold (though some of it turned out to be exploitation pyrites). Severin followed in June with their big mid-year sale and I ordered their nine-release bundle before all the titles had been announced. I should probably be scrawling a message on my wall in blood saying “Stop me before I do it again!” I assumed I’d have finished the Vinegar Syndrome cache by the time my big Severin bundle showed up – and no doubt I will, as a month later Severin still hasn’t shipped my order and there are only two VS disks left from the sale (though my July bundle arrived last week!).

*

Televised Terror (Various, 1978-90)

Although they didn’t get a lot of respect, made-for-television movies were a fertile ground for writers, directors and actors from the mid-’60s into the ’90s. This is largely explained by two connected developments in the movie industry. With the rise of television throughout the 1950s and the breaking up of studio monopolies in production, distribution and exhibition following the Supreme Court’s Paramount divestment decree in 1948, studios gradually abandoned the B-movie units which had not only provided supporting features for double-bills but also served as a training ground for actors and crew people. Initially, much of the slack was picked up by smaller exploitation companies. At the same time, the increasing demand for programming to keep eyes glued to the TV screen wasn’t being fully met by the studios’ continuing reluctance to make their productions available – after all, why should they feed the opposition? Network television had to wait a couple of years before they could access new releases, and then it was often with restrictions on how many times a movie could be shown.

And so TV-oriented production companies began to make features specifically aimed at the broadcast networks. Naturally there were issues to be dealt with; television had more restrictions on what could be shown than theatres, something which became increasingly apparent as the ’60s and ’70s saw greater freedom on the big screen for displays of sexuality and violence. Television needed to compete in a more permissive marketplace while adhering to tighter content rules. That need to compete often brought a censorious backlash as members of the more diverse television audience took offence at what was being beamed into their homes. One of the first features specifically made for TV, Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964), was pulled from the schedule when it was deemed too violent for home viewing and was given a theatrical release instead.

Over the next several decades, probably thousands of movies were made for television, but the ones which are best remembered are no doubt the horror, sci-fi and thriller movies which – at least in the ’60s and ’70s – fed an appetite only sporadically serviced by theatrical productions. While violence had to be restrained, these movies, like Paul Wendkos’ Fear No Evil (1969) and The Brotherhood of the Bell (1970), often compensated by creating an effectively disturbing atmosphere through supernatural and psychological disturbance.

Vinegar Syndrome recently released a three-disk set which promises to be the first of a new series devoted to Televised Terrors. To be honest, the packaging seems a little misleading; these aren’t horror movies, but rather mystery and suspense. What makes the set particularly interesting, though, is that it – whether purposely or inadvertently – illustrates the evolution of TV content across three decades.

in Walter Grauman’s Are You in the House Alone? (1978)

Are You in the House Alone? (Walter Grauman, 1978)

Walter Grauman’s Are You in the House Alone? (1978), based on a young adult novel by Richard Peck, has superficial similarities to theatrical movies of the time, like Halloween (1978) and When a Stranger Calls (1979), but the stalker elements are used in service of something like a grimmer after-school special about the impact of rape on a high school student. Gail Osborne (Kathleen Beller) begins to find ominous notes tucked into her locker, and there are heavy-breather phone calls at home. While she navigates a burgeoning relationship with fellow-student Steve (Scott Colomby), she’s also becoming aware of stresses in her parents’ marriage which make her mother (Blythe Danner) overly controlling. Facing distrust and accusations from Mom and Dad (Tony Bill) and very unhelpful advice from the school counsellor (Ellen Travolta), Gail has to face an escalating threat by herself.

When the rape finally occurs, she’s afraid to name her attacker because no one is likely to believe that a popular student from a wealthy family is actually a violent sociopath. Cast in the form of a thriller, Are You in the House Alone? is actually an effective examination of what we now call rape culture in schools and on college campuses. The uncomfortable objectification of girls which leads privileged boys to take for granted that they have an unfettered right of access to their bodies extends to the creepy art teacher (Alan Fudge) who constantly makes inappropriate comments about Gail in class and is always looking for excuses to get her alone.

The movie’s didactic purpose is effectively carried by strong performances, particularly from Beller, who transitions from doubt and fear to an angry determination to regain her own autonomy even as she recognizes that the society she lives in will never give her justice (after she does name the assailant, she’s told bluntly that his status and the fact she herself was not a virgin at the time of the attack guarantee that there will never be a conviction). Danner and Bill as her parents, Travolta as the counsellor and Fudge as the creepy teacher provide strong support, but remain subservient to Gail’s story.

in William A. Graham’s Calendar Girl Murders (1984)

Calendar Girl Murders (William A. Graham, 1984)

Made six years later, William A. Graham’s Calendar Girl Murders (1984) ditches any pretense of a socially responsible purpose. The influence of the giallo and slasher movies of recent years is obvious, but even in the mid-’80s regulations constrained what was possible on television and the results are more than a little absurd as the movie tries to be salacious without actually showing much. Centred around a Playboy-like magazine run by a Hugh Hefner-like publisher, it’s forced to suggest rather than show sexuality and ends up giving the impression that everyone is just play acting. It’s hard to take the attempts at suspense seriously because the stakes never seem even remotely real.

Wealthy Richard Trainor (a bored-looking Robert Culp) is unveiling his latest “playmate” calendar at a gala where drunken ex-celebrity Nat Couray (Robert Morse) butchers Neil Sedaka’s “Calendar Girl”. Miss January, also drunk, makes a poor impression for the TV cameras and returns to her room upstairs at the hotel. A POV shot follows her to the balcony and she falls to her death. Suicide or murder? Detective Dan Stoner (Tom Skerrit) is suspicious and his suspicions are confirmed when Miss February is done in. Trainor doesn’t want to cooperate, even as the killer moves chronologically through the calendar.

Stoner, although happily married to Nancy (Barbara Bosson) and with a young son, quickly falls under the spell of Cassie Bascomb, an office worker who briefly dabbled with modeling for Trainor, but left the business for some vague reason involving one of the company photographers. Although Cassie is played in full I’m-definitely-going-to-be-a-star mode by Sharon Stone, in her mid-twenties and still eight years away from Basic Instinct (1992), it’s never convincing that Stoner would ditch his personal life and professionalism for this woman, as attractive as she might be, so one of the movie’s main (if flimsy) dramatic hooks never really takes hold. What is interesting, though, is the dynamic which turns up so much more fully developed in Basic Instinct, with a much less ambiguous conclusion.

With the sex tamped down – despite all the talk of pornography and nude photography, all the models necessarily remain covered up for television – the movie has to focus on the mystery, drawing at least a little from giallo-inspired slashers. For visual interest, there are a number of fashion photo shoots which echo the sex-and-violence chic of Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), but what could have been as sleazily exploitative as a Lucio Fulci film has a timid quality which is not really off-set by a barely sketched mystery with a final reveal you can see coming from a long way off.

Child in the Night (Mike Robe, 1990)

By the end of the decade, while sex was still problematic, it was possible to show more violence on television and Mike Robe’s Child in the Night (1990) opens with a killing which echoes the Friday the 13th and Halloween theatrical franchises. Businessman Scott Winfield (Stephen Godwin), on his way to pizza with his young son, stops at the office to pick up some papers. As he opens the safe a dead bird is thrown through the window and he tells the boy to hide as he heads outside. Hearing voices, the boy creeps to the broken window in time to see his Dad brutally killed by a man in a yellow rain slicker who wields a big cargo hook.

As the cops deal with the aftermath, a consulting psychologist is called in to handle the boy, who refuses to stop clinging to his Dad’s dead body. Dr. Hollis (Jobeth Williams) doesn’t want to be there because she has some PTSD of her own, having had to deal with a bizarre disaster in which a plane crashed into a school playground, killing and traumatizing a whole bunch of elementary school kids; she was unable to help one of the survivors, who ended up killing himself. Hollis swore off working with kids, but her boss calls to interrupt her dinner date because no one else is available. At the scene, she manages to get the boy away from the body and she’s trapped because the kid immediately becomes dependent on her and the investigating detective insists that she remain on the case because he needs to know what his only potential witness saw.

The kid, by the way, is played by nine-year-old Elijah Wood in his first big role and he does a good job of portraying a boy suppressing horrific memories which insist on resurfacing in various ways – the doc gets him painting pictures and he filters what he saw through the story of Peter Pan, conflating the killer with Captain Hook, which eventually leads to a genuinely disturbing moment when he finally remembers a very Freudian primal scene involving his mother and Captain Hook, or rather the real-life model for Hook. Along the way there are more killings and a bunch of red herrings in the form of Winfield’s partners in his yacht-building business.

And of course there’s a burgeoning romance between Hollis and lead investigator Detective Bass (Tom Skerrit again), who wavers between his attraction to her and his irritation with her continuing resistance to working with the boy and her caution about pushing him too hard to remember. The final revelation of the killer’s identity may not be too surprising, but it is kind of creepy.

All three of the movies in the set echo things going on in theatrical production at the time, and they all have pretty good casts for the most part giving decent performances, but none of them can escape a feeling of being tamped down or held back by network standards. That would all change the year Child in the Night aired when ABC took a chance on David Lynch and Mark Frost and financed the first half-season of Twin Peaks (1990) … that series launched a frontal assault on broadcast standards and, along with the rise of cable, paved the way for more small-screen sex and violence than anyone had dreamed off during the previous couple of decades.

All three movies look excellent on Vinegar Syndrome’s Blu-rays. The only extras are two brief audio pieces by Amanda Reyes, a fan of made-for-TV movies (she wrote a book about them) on the Are You in the House Alone? and Child in the Night disks, and a feature-length conversation about the genre between Reyes and film historian Sam Pancake on the Calendar Girl Murders disk. There’s also an interview with composer Charles Bernstein about his score for Are You in the House Alone?

*

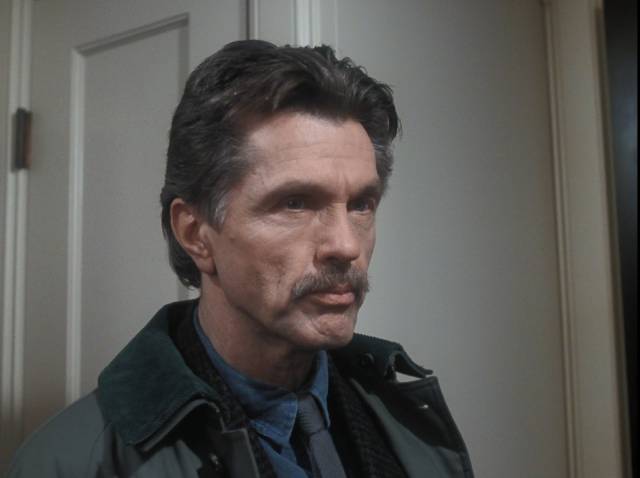

All-American Murder (Anson Williams, 1991)

Although All-American Murder (1991) had a theatrical release, its aesthetic is that of a higher-end direct-to-video or made-for-cable movie, drawing on elements of the ’80s slasher cycle and (maybe giving away too much) a bit of Noel Black’s wonderful Pretty Poison (1968). Who knows what it might have been like if original plans had worked out, because at the start none other than Ken Russell was attached to direct. When that fell through, the project became the theatrical feature debut of Anson Williams, Potsie on Happy Days (1974-84), who had started directing episodic television and the occasional small-screen feature in the mid-’80s. Stylistically, the movie is straightforward and functional rather than inventive, but Barry Sandler’s script is strong enough to keep its head above genre cliches. (A few years earlier Sandler had written and produced the more perverse Crimes of Passion [1984] for Russell.)

When bad boy Artie Logan (Charlie Schlatter) is kicked out of yet another school (accused of burning down his dorm – though he claims innocence), his unsympathetic father, a judge (Tim Green), sends him to Fairfield College for one last chance. There he’s immediately attracted to popular girl Tally Fuller (Josie Bissett, who had debuted a couple of years earlier in Umberto Lenzi’s Hitcher in the Dark) and he sets out to win her – though not before hitting the sheets with the Dean’s promiscuous wife (Joanna Cassidy).

Tally seems to return his interest, but when he arrives at her residence for a second date, she falls from a balcony in flames and dies a horrible death. Witnesses see Artie at the scene and immediately finger him to the police, an accusation given some weight by his previous suspected arson. The investigating detective isn’t so sure, despite his colleagues wanting a quick resolution, and he gives Artie twenty-four hours to clear himself. Although there are a bunch of red herrings, whenever there’s an additional murder Artie somehow manages to be at the scene, looking increasingly guilty. In the end, it turns out that the cop has been using him as bait to draw out the real killer … with a climactic revelation which isn’t much of a surprise, but does wrap things up effectively.

All-American Murder manages to evoke a number of better, more well-known movies, but it zips along and remains entertaining. The real attraction, however, is Christopher Walken as Detective Decker, the cop who takes as much pleasure in irritating his less imaginative colleagues as he does in tormenting Artie. Having someone of his stature in a major supporting role elevates the movie to a level it wouldn’t have otherwise attained and you keep watching the sometimes mechanical plot waiting for him to pop up again.

The disk includes a commentary by slasher fans The Hysteria Continues, plus interviews with Schlatter and cinematographer Geoffrey Schaaf.

*

Champagne and Bullets (John De Hart, 1993)

At least Anson Williams displays professional efficiency. That can’t be said for John De Hart, a lawyer who has one movie to his credit … or credits. De Hart wrote, produced, directed, composed the score, sang a bunch of songs and played the hero in Champagne and Bullets … or Road to Revenge … or Geteven… Its original 99-minute version was completed in 1993, but De Hart was unsatisfied and continued tinkering with it for years before settling on Geteven in 2006, for which he even shot some new footage, although it’s nine minutes shorter (the second version, Road to Revenge, is only 75 minutes). I have to confess that as of now I haven’t watched the two re-edits or listened to De Hart’s commentary because my initial viewing of Champagne and Bullets felt as if it was causing irreversible brain damage. To put it bluntly, De Hart had no clue about how to make a movie and most of his missteps lack the charm of, say, Christopher Thies’s Winterbeast (1992).

De Hart plays a cop who is framed, along with his partner, by their crooked commander who eventually becomes a judge who leads a Satanic baby-sacrificing cult. Which sounds pretty awesome, especially when you see that the villain is played by the great B-movie star William Smith and the partner is none other than the wildly unpredictable Wings Hauser. But De Hart doesn’t know how to shoot a scene, doesn’t know how to edit for pace, and despite being a guy nearing middle age obviously fancies himself a matinee idol – he lingers on himself and frequently removes his clothes to get jiggy with younger women, which feels kind of creepy … but that’s not all: he lingers for minutes on end as we are forced to listen to his mediocre songs in their entirety, not even bothering to move the camera a little or cut to another angle to relieve the tedium.

We can only hope that De Hart is a good lawyer, because listening to him deliver Hamlet’s entire soliloquy in a bar for no reason at all demonstrates conclusively that he’s no actor. Even Smith has trouble breathing life into the villain because he gets no support from his director. Only Hauser manages to make something of a bad situation as he obviously lets loose with some absurd improvisations several times which have nothing to do with the story and give the impression that as an actor he’s crying out in pain and frustration at what he’s being subjected to.

When painful memory fades, I may take a look at the variant cuts, but for now Champagne and Bullets stands as one of the worst cinematic atrocities I’ve ever seen.

*

Nightmare Weekend (Henri Sala, 1985)

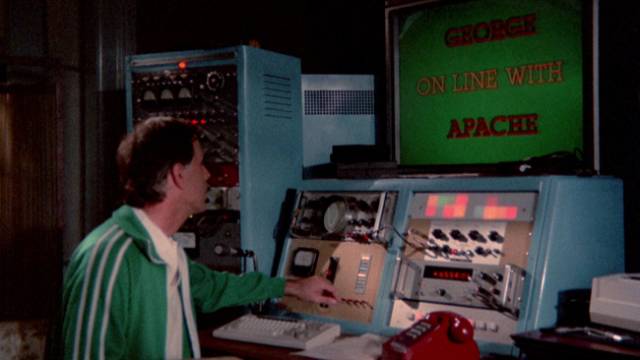

Having said all that, it may seem hypocritical to say that I kind of enjoyed Henri Sala’s Nightmare Weekend (1985), which itself is not what you’d want to call a good film. But its non-goodness is laced with enough weirdly imaginative elements to relieve the occasional tedium with a WTF laugh. Foremost among these surprises, introduced right at the start, is an animated puppet named George which turns out to be an interface with a sentient AI system and also the best friend of the AI creator’s daughter Jessica (Debra Hunter). She plays games with George which, through the AI, affect the real world – a racing game takes control of a car and sends it on a wild drive, eventually crashing it into a tree.

Dr. Brake (Wellington Meffert) has designed the computer as a “therapeutic” tool which can alter behaviour through some kind of computer magic (it takes an object which has some association with the subject, turns it into a silver ball which is somehow shot into the subject’s mouth and … does something … better not to ask what!). He’s been testing it on animals, but there have been negative side effects. His venal assistant Julie Clingstone (Debbie Laster) is pushing for human trials because, unknown to the doc, she has made a deal with a sinister corporation. Working on her own, she has invited three college girls to the estate for the weekend and launches an experiment with them as subjects; but rather than providing therapy, she turns them into psychotic monsters.

While many of the cast don’t seem to have appeared in any other movies, Dale Midkiff as Jessica’s biker boyfriend went on to Pet Sematary and a lengthy television career, while creepy guy from the local bar Robert John Burke immediately moved on to a number of Hal Hartley movies, Dust Devil, and a busy career in features and television which to date has reached ninety credits.

There are some fairly effective gore effects – somewhat inconsistent for an amusing reason: the French director and production team kept changing the script but didn’t bother to translate it for the American crew, so makeup effects artist Dean Gates was creating effects which were no longer in the script. The sci-fi/horror elements are wacky and amusing, occasionally reminiscent of Phantasm (1979), but they’re spread a little thin, with more time taken up by lengthy stretches of soft-core sex – not surprising, perhaps, as director Sala was a prolific maker of French hardcore movies.

A thesis could probably be written about European exploitation filmmakers shooting strange genre movies in Florida. Usually these were slasher-oriented thrillers by giallo and horror directors, so Sala and Anglo-Indian producer Bachoo Sen get points for the absurd fantasy elements here.

Along with an impressive new transfer of the original uncut version, the disk includes interviews with Gates and crew member and bit player Marc Gottlieb which provide some amusing stories about the confusion arising from the multi-national nature of the production and the resulting language problems. There are also a few minutes of alternate R-rated scenes.

To be continued…

Comments