Vinegar Syndrome summer binge, part three

in Randall Badat’s Surf II (1983)

Surf II (Randall Badat, 1983)

I’m not a big fan of teen comedies – I did see Porky’s in a theatre back in the day, but I haven’t seen any of the American Pie movies – so I probably wouldn’t have bought Vinegar Syndrome’s deluxe edition of one-shot director Randall Badat’s Surf II (1983) if it hadn’t been part of their big mid-year sale bundle. They promoted it as a big rediscovery, but I had modest expectations. The first thing I noticed as I started watching the longer director’s cut was that it looked pretty polished and must have had a decent budget because the nicely photographed and edited surfing montage under the main titles was invigorated by a Beach Boys track. As it turned out, the soundtrack alone must have cost what might have been the entire budget of some throw-away teen comedies.

The next thing I noticed was that the script was full of dumb wordplay which, delivered by a surprisingly good cast, quickly had me laughing out loud. And I do mean dumb. The local top cop is Chief Boyardie (Lyle Waggoner), whom everyone keeps referring to as “Chef”, while his second-in-command, whose name we first hear as he ogles girls in bikinis, is Inspector Underwear (Ron Palillo). Totally juvenile, but delivered with unironic enthusiasm. The tone and energy are sustained to the end, along with some genuine stylistic invention – we meet our two heroes’ middle-class families in an in-camera split screen which mirrors identical sets with identical pairs of parents speaking identical banal dialogue in perfect unison; these highschoolers are kicking against numbing social limitations with their rebellious beach-bum surfer attitudes.

But there’s more here than just some coming-of-age comedy set against a background of sun, sand and surf, because lurking off the beach in an underwater lab is the ultimate nerd using his scientific smarts to get revenge on the popular kids who made his growing-up hell. Menlo Schwartzer (Eddie Deezen) has invented a toxic soft drink called Buzzz Cola which is manufactured and distributed by our heroes’ fathers and it’s transforming the local high school kids into punk-rock zombies. It’s up to Chuck (Eric Stoltz in his first lead role) and Bob (Jeffrey Rogers) to defeat Menlo’s evil plans, while also trying to win a surfing competition despite Chief Boyardie’s orders to close the beach … not to mention hanging out and getting stoned with their girlfriends.

An update of Frankie Avalon/Annette Funicello beach movies, with a nod to The Horror of Party Beach (1964), Surf II is funny, gross (an “eating contest” between the boys’ friend Johnny Big Head [Joshua Cadman] and head zombie Jocko [Tom Villard] in which they guzzle handfuls of seaweed and dead fish is pretty stomach-turning), witty and visually inventive. How it ended up being Badat’s sole feature (which started out as a straight horror script) is covered in the extensive extras, which include commentary tracks on both the director’s cut and the re-edited theatrical version (which each get their own disk) as well as a long retrospective making-of which interviews Badat, producer George Braunstein and multiple crew and cast members.

Perhaps even for the early ’80s, Surf II was a bit too weird for its target audience and it disappeared fairly quickly, with limited visibility on home video until this impressive restoration. It may not have helped that its very first joke was misleading – there never was a Surf I. I was surprised and entertained despite (or is that because of) having no real expectations. This is definitively an instance of the benefit of a company like Vinegar Syndrome offering bundles of their new releases.

*

Scanner Cop/Scanner Cop 2

(Pierre David/Steve Barnett, 1993/1994)

Also included in that sale bundle was a double-feature box set – containing both 4K UHD and Blu-ray disks – of Scanner Cop 1 and 2, neither of which I’d ever seen before. In fact, I haven’t even seen the two direct sequels to David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981). That is far from my favourite Cronenberg and the concept has never seemed interesting enough to follow up. Again, I acquired this new release largely because it was in the bundle (which I had actually paid for long before all the included titles had been announced – so, an act of faith in the good judgment of the folks at Vinegar Syndrome).

The two Scanner Cop movies were relatively low budget, direct-to-video releases, which take place in a world where the existence of scanners is widely-known, with a drug used to suppress their psychokinetic powers because they’re so uncontrollable that they cause dangerous psychoses. In the prologue to Scanner Cop (1994) – the directorial debut of Pierre David, the producer of Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979), Scanners and Videodrome (1983) – a boy sees his scanner dad go crazy and has to use his own powers to save the life of cop Peter Harrigan who’s come to check out the disturbance. Improbably, the cop takes the boy home and adopts him. He grows up to be Sam Staziak (Daniel Quinn), who follows in his adoptive dad’s footsteps to become a cop himself.

When a series of cops are killed in seemingly random attacks by people who have never before shown signs of violence or antisocial behaviour, dad, who is now the police chief (Richard Grove), asks Sam to forego his drugs for a while so he can scan the mind of a surviving attacker who’s now in a coma. The session takes a heavy toll, but crucial clues are gleaned from the confusing imagery he pulls from the man’s head. Despite the risks, Sam refuses to resume the suppressing drugs while he’s on the team investigating the case, even though his grip on reality begins to slip.

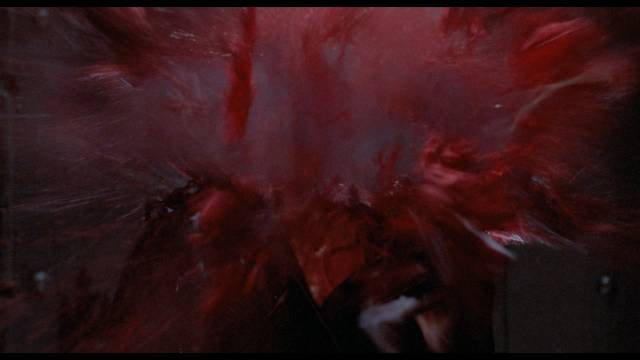

Eventually, Sam’s powers lead to Karl Glock (Richard Lynch), who is using radical mind control techniques to transform regular people into assassins in an elaborate plan to get revenge on Harrigan for once having shot him in the head during a violent arrest. There’s an inevitable mind-blowing showdown and Sam’s scanner powers are recognized as a valuable crime-fighting tool – so essentially Scanner Cop is a superhero origin story. In David’s hands, it’s an efficient B-movie. Richard Lynch is, as always, a good villain, but the sequel benefits from a better one.

in Steve Barnett’s Scanner Cop 2: The Showdown (1994)

In Steve Barnett’s Scanner Cop II: The Showdown (1995) Patrick Kilpatrick (dad in The Cellar) is Karl Volkin, a rogue scanner who manages to stop taking his drugs while imprisoned in an asylum for the criminally insane and uses his powers to escape. On the outside he starts tracking down and killing other scanners, who are left as shrivelled husks. It doesn’t take long for Sam to figure out, with the help of Carrie Goodhart (Khrystyne Haje), a counsellor he’s consulting about his own mysterious background, that Volkin has discovered a way to absorb other scanners’ powers and he’s rapidly becoming so powerful that even Sam’s powers may be insufficient to defeat him.

The sequel isn’t really any better than its predecessor, but Kilpatrick’s enthusiasm as Volkin does make it more entertaining. Additionally, there’s no longer any need for Sam to be struggling with his own powers, so he can just get on with the job of fighting the villain. Because both movies take for granted the existence of scanners, neither spends any time on Cronenberg’s theme of scientific irresponsibility; like any routine genre movie, they simply get on with telling a story with some action, some gore, and some perfunctory character development. Do they warrant UHD restorations? Maybe not, but they’re entertaining enough, and it’s nice to have them packaged together in a handsome set.

There’s a lengthy making-of doc spread across the two disks, plus a commentary track for each movie.

*

Six String Samurai (Lance Mungia, 1998)

Finally, and obviously intended as the sale bundle’s pièce de résistance, an obscure little movie called Six String Samurai (1998) is the second feature to get Vinegar Syndrome’s high-end box packaging (following Don Coscarelli’s The Beastmaster which was released as part of last Fall’s Black Friday sale bundle). I’ve mentioned before that I’m partial to post-apocalyptic movies; I’m also partial to movies which mix genres, so this looked like a good bet. My intuition proved correct. I really enjoyed this movie, made for peanuts by co-writer/director Lance Mungia in his mid-twenties with a Panavision camera package donated free of charge by company marketing executive Tracy Morse. This last point is crucial, because it gave the movie a high-budget sheen it would never have had if Mungia and first-time cinematographer Kristian Bernier had been limited to a budget-feasible 16mm.

Shot piece-meal mostly in Death Valley, the production apparently burned through crew members quite frequently (some would refuse to leave their vehicles because of the heat), but again the use of locations gives the movie a sense of scope which provides echoes of spaghetti westerns and samurai movies, two of the genres which Mungia weaves into the mix. This arid canvas provides the backdrop for a series of comic-violent encounters between hero Buddy (co-writer Jeffrey Falcon) and various post-apocalyptic gangs who are trying to prevent him from reaching Lost Vegas where he intends to compete for the position left vacant by the recently deceased King. Elvis was the ruler of the only remaining free place in the U.S. after Russia took over the country following a nuclear war in 1957, and his death has left a power vacuum which many hope to fill.

Buddy, dressed in a black suit, wearing Buddy Holly glasses and carrying a guitar which also serves as a sheath for a katana, is walking across the wasteland when he inadvertently saves the life of a young boy whose mother has just been killed by a gang of perhaps would-be cannibals. Buddy dispatches them all with his blade and continues on his way, the Kid (Justin McGuire) following him despite obviously not being welcome. During ensuing encounters, it turns out that the Kid has skills which prove useful to Buddy’s own survival. There are fights with both swords and kung fu, pursuits, explosions and occasional outbursts of music. Among Buddy’s rivals are a variety of gangs reminiscent of those faced by The Warriors in Walter Hill’s genre-bending movie of that name.

These include The Red Elvises, who also provide tracks woven into the score by composer Brian Tyler, whose second feature this was (helping to launch a long and prolific career – his latest credit is Fast & Furious 9). So Six String Samurai is almost a musical, along with all the other genres.

Also involved in Buddy’s odyssey is Death himself, pursuing across the wasteland with his own gang. When Death finally catches up with him, Buddy gets into a guitar duel with the big guy… while the final image is an overt reference to The Wizard of Oz, with Buddy walking away on a road which curves towards the magical towers of Lost Vegas in the distance.

Six String Samurai is one of those movies which follows its convictions wherever they lead (like favourites such as Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce [1985], W.D. Richter’s Buckeroo Banzai [1984] and John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China [1986]), trusting its audience to go along with whatever happens. That gives its absurdities an air of authenticity; there’s no hedging, no self-protective distancing via irony. It sets up its world and inhabits it fully. If you can’t accept that world and its often ridiculous details, you won’t like the movie, but if you go along it’s really entertaining. This is due as much to the presence of Falcon in the lead, playing the laconic hero to the hilt – he came by his fighting skills legitimately as a performer in Hong Kong action movies during the decade leading up to Six String Samurai – as it is to Mungia’s grasp of all the genre conventions and Bernier’s excellent widescreen cinematography.

Vinegar Syndrome have given the film a spectacular 4K transfer from the original negative – you can almost see every grain of sand, every thread in the costumes, every streak of dirt on the characters sweating in the Death Valley sun – and supplemented it with two commentary tracks (Mungia and Bernier on one, Mungia solo on the other), plus a 76-minute making-of (in four parts) by Mungia, which evokes the experience of cast and crew in vivid detail, making much more inventive use of Zoom than most similar projects trying to get around Covid-enforced restrictions. There’s also Mungia’s 1996 student film A Garden for Rio (15:08).

*

I’ve been enjoying Vinegar Syndrome’s releases so much that I actually bought their half-year subscription guaranteeing that I’ll receive every new bundle through December. (I received the most recent bundle a couple of weeks back: two low-budget ’80s regional horrors from Texas – Tom Daley’s The Lamp [1987] and Gary Marcum’s Through the Fire [1988] – plus Jeremy Hoenack’s Killer’s Delight [1978], with Daughters of Darkness and Dark Shadows’s John Karlen as a serial killer haunting California backroads in a white van.) Who knows, maybe I’ll go for the full 2022 subscription when it becomes available at the next Black Friday sale.

Comments