Cauldron Films, round three

The third round of releases from Cauldron Films, despite – or perhaps because of – expectations, left me disappointed. This time they’ve unearthed a pair of relatively obscure found-footage movies. This is a genre fraught with problems, but I’m kind of partial to it, even when the execution is a bit rocky. At its best, it can provide deep and long-lasting chills, underlining disturbing events with an air of (necessarily contrived) realism. From Jean-Teddy Filippe’s Les documents interdits (1989) to the BBC’s Ghostwatch (1992) to the first couple of minimalist Paranormal Activity movies (2007, 2010) to The Last Exorcism (2010), the immediacy of faux documentary amplifies the creepy atmosphere and adds a kick to the jump scares.

The most difficult trick is to find a way to justify the continued recording of events – why keep running a camera when things get really dangerous? Although The Blair Witch Project (1999) put found-footage on the commercial map, it actually embodies some of the genre’s chief flaws; while the first half has a convincingly mundane tone justified by the students’ purpose, once things become threatening and it seems that time and space are distorting it becomes harder to believe anyone would bother to grab the camera and start filming when each new threat arises … and more particularly, the resulting chaotic imagery obscures rather than reveals, ultimately relying on the audience to conjure up whatever horror the characters meet in those climactic moments. This is the genre’s most irritating trope, the final refusal to offer any genuine revelation or resolution. Ambiguity is all very well, but it needs to have a firmly established foundation and too many found-footage movies neglect this in favour of characters running around and acting scared in response to things withheld from the audience.

The big question is always why use this approach rather than a more straightforward narrative technique. One reason is that it seriously constrains point-of-view, which in turn helps to limit budget – we are limited to what just a few characters are able to see, so it’s more likely we’ll just get glimpses of something an objective point-of-view would require more of. But limiting things too much becomes frustrating. It’s a balancing act.

And sometimes it just seems unnecessary. I love Richard Raaphorst’s Frankenstein’s Army (2013), but the found-footage technique is an unconvincing distraction best ignored; worse, it violates the technical limitations of the equipment supposedly being used – a problem all-too common to the genre. In that case, it’s small 1940s newsreel cameras, which were limited to only a few minutes per load and even if capable of recording sound certainly couldn’t capture the range we hear in the movie. In more contemporary examples there’s the ever-present issue of battery capacity. These might seem like nits which it’s unfair to pick, but they’re built into the concept and ignoring them undermines the verisimilitude the form is striving to achieve.

Some of these kinds of technical questions nagged at me as I watched the new Cauldron releases, along with those conceptual issues already alluded to. Both films have good points, but both are at least partially undone by these problems.

The Collingswood Story (Mike Costanza, 2002)

The most interesting thing about Mike Costanza’s The Collingswood Story (2002) is its use of video chat technology to tell its story before that was a common thing. Everything we see is on the computer screens of the two main characters, Rebecca (Stephanie Dees) and Johnny (Johnny Burton). Becca has just moved to another town to go to college and her older boyfriend Johnny has installed videophone software on her computer so they can continue to see and talk to each other. From our perspective, this technology seems both prescient and dated – the former because we all now use Zoom and its like to maintain personal and work connections, the latter because the design seems quaint in the way computers so often appear in older movies which are trying to convey a cutting-edge impression.

The big limitation here is that Becca and Johnny are tied to their computers, which makes for a very static mise-en-scene. Johnny sits in his apartment with a bookcase behind him and beside that a door which you just know, like Chekhov’s gun, will come into play in the third act; and Becca mostly sprawls across the bed in the room she’s rented in a big old house. Eventually, Becca does move around, carrying her laptop – amusingly tied to her modem by a cable because this is all before wi-fi. She buys a 100-foot cable which enables her to make a trip up to the attic for a very Blair Witchy climax.

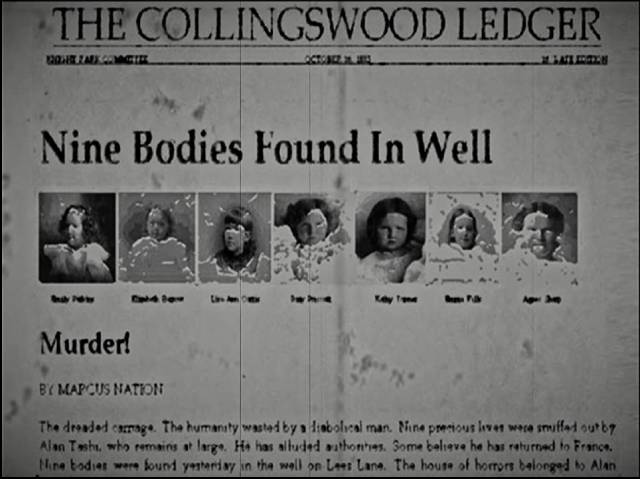

Having set up the mechanics, Costanza kicks the narrative into gear by having Johnny arrange for an on-line psychic consultation on Becca’s birthday. The psychic, Vera Madeline (Diane Behrens), seems like a typical phony, offering vague generalizations before seeming to show some genuine ability by saying Rebecca’s name although she initially offered a fake one. Then, after the call, the psychic calls Johnny and provides some unsettling background information about the town Becca has moved to, triggering some on-line research which reveals that there was once a murderous cult there and that there’s a connection to the house Becca is in.

Although Johnny urges Becca to get the hell out of the house, she decides to explore. This is where things get awkward, because she drags her computer with her up the ladder to the attic (still attached to that cord). Ostensibly this is so that she won’t be alone as she goes up there, though obviously there’s nothing Johnny can do if she runs into trouble … which she naturally does, as that door in Johnny’s room opens unnoticed behind him…

While Costanza deserves points for innovation – we take omnipresent screens and non-stop connections for granted now, but this stuff was not in wide use back in 2002 – and his choice allows him to limit most of the movie to just two characters, with only two other brief speaking parts and brief glimpses of a third sinister figure, he doesn’t entirely play fair. The claustrophobic constraints of the videophones are interrupted a couple of times with montages involving the cult’s activities which appear to be dreams Becca has – each ends with her waking abruptly – which is an absolute violation of the whole concept; there’s no possibility of subjectivity in found-footage.

On the plus side, performances are good, particularly Dees as Rebecca, who is plucky and charming and increasingly irritated by boyfriend Johnny whose growing concern does little except make her nervous about being alone in the old house. All the technical restrictions prevent either actor from really exploring their characters, relegating them to functions within the conceptual machinery, but they nonetheless manage to leave an impression even if the story never really gels or finds a satisfactory resolution.

Cauldron’s Blu-ray looks fine considering the nature of the production – it was mastered from the original tapes – and there’s a director’s commentary and interviews from 2005 with Dees, Burton and Grant Edmonds (who plays Johnny’s slacker friend Billy), plus a brief archival making-of.

*

1974: La posesión de Altair (Victor Dryere, 2016)

Much closer to the traditional found-footage form is Mexican filmmaker Victor Dryere’s 1974: La posesión de Altair (2015). One thing that appealed to me immediately was the fact that Dryere shot the film on super-8mm film stock, rather than video, justified by setting it back when videotape wasn’t yet a common consumer format. This gives the film a nice grainy texture, supporting a home movie quality – at least, to a degree. The decision to reframe the image from 1.33:1 to 1.78:1 immediately alters that impression of amateur naturalism; it becomes more like an actual movie, making the super-8 more of an affectation than a signifier of authenticity. An elaborate soundtrack with clear dialogue and layered ambiences which blend with a minimal score also creates a problematic distance from what the film is pretending to be – a collection of artless home movies which inadvertently provide a record of a couple beset by increasingly menacing supernatural events.

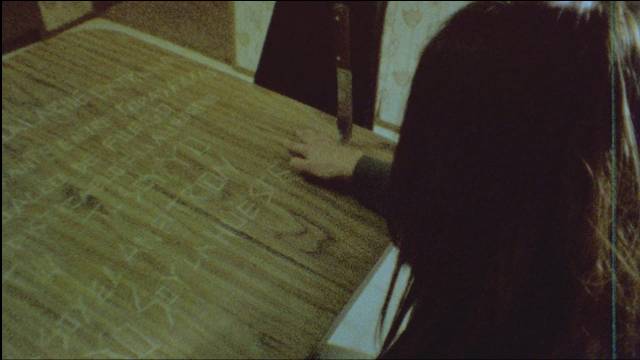

Altair (Diana Bovio), a teacher, and Manuel (Rolando Breme), a toy-maker, are recently married and moved into a new house in a heavily wooded rural area. Manuel, to Altair’s frequent irritation, documents every moment with his 8mm camera. It’s all very ordinary, even mundane, in the early stretches, with little moments of intimacy and affection. But gradually odd things happen. Dense flocks of birds gather over the house – and eventually crash into it, falling like hail to litter the ground with their broken bodies. And Altair begins to have disturbing dreams. In them, she reports encounters with intimidating figures which she believes are angels.

Slowly Altair becomes more and more withdrawn. She says the angels speak to her, they instruct her to do things like constructing “doors” in the bedroom and cellar with bricks which have mysteriously appeared in the garage. She kneels before these “doors” and mutters to herself as if praying and, unnervingly, seems to be able to pass through them. As Manuel becomes increasingly concerned, she stops communicating altogether.

Altair’s sister (Blanca Alarcón) isn’t very helpful when Manuel asks about her past, although he eventually learns that they once had a brother who disappeared mysteriously. A doctor (Ruben Gonzalez Garza) who is called in provides an audio cassette of a therapy session from Altair’s childhood which suggests that she has been visited by these angels before. In a climactic flurry, we get some very brief glimpses which indicate the (not very surprising) true identity of the angels.

Nothing is terribly new about the film’s events or that vague resolution, but Dryere does generate some unsettling atmosphere and Bovio and Breme give good performances. The evocation of the ’70s is convincing thanks to careful production design (though the appearance of a Rubik’s Cube feels a bit off – it was actually invented in 1974, but wasn’t made commercially available until 1980). But as the film is framed by a news report about the disappearance of the couple, Altair’s sister and Manuel’s friend Callahan (Guillermo Callahan), with police on the scene and the doctor hurrying away with a box full of Manuel’s film reels, we known from the start where everything is going so the accumulation of small incidents lacks any real sense of urgency or surprise.

Because of the tone and texture provided by the period setting and the look of the 8mm imagery, I wanted to like the film more, but it felt too familiar and predictable to be really scary. Maybe it’s just me, but that final glimpse which “explains” the film’s events not only felt like a tired cliche – it made much of what had preceded it, the apparently supernatural manifestations, senseless.

Recent hints suggest that Cauldron will be heading back towards Italian action and horror in future releases. Although I respect them for exploring different areas, I’ll be happy if their next batch contains a solid, previously not seen poliziottescho.

The 1974 disk includes only a very brief extra with sound designer Uriel Villalobos; there’s also a CD, which is an odd choice as there’s so little score (by Enrico Chapela) and most tracks are just effects and ambience.

Comments