Hammer Vol. 6: Night Shadows from Indicator

Indicator took a break from their series of Hammer Films box sets as they branched out to release Columbia Noir 1-3 (volume 4 arrived a couple of weeks ago and will be reviewed here soon), The Fu Manchu Cycle and John Ford at Columbia. Hammer Volume 5: Death & Deceit was released in March 2020, but Volume 6: Night Shadows wasn’t released until the end of June this year. It’s been sitting on the shelf here for two-and-a-half months while I’ve tackled numerous other disks … perhaps because the four films in this set didn’t seem particularly inspiring. No doubt rights issues have been responsible for the impression that Indicator have been circling just beyond the core body of Hammer’s most prominent productions – their hugely influential Gothic horrors which have turned up on Blu-ray from other sources. On the other hand, this archaeological digging on the fringes has brought to light a number of less well-known but nonetheless interesting titles.

While previous sets were anchored by at least one really strong film, this new one looked a trifle middling. There are two atmospheric black-and-white thrillers hampered by weak scripts, one colourful historical adventure, and one of the studio’s updates of an old Universal horror property. Having finally got around to cracking the set open, I enjoyed it more than expected.

in John Gilling’s The Shadow of the Cat (1961)

The Shadow of the Cat (John Gilling, 1961)

The Shadow of the Cat (1961) was the first feature directed for Hammer by John Gilling, who had attracted their attention with his excellent Burke and Hare movie The Flesh and the Fiends (1960). Ironically, Hammer’s name is nowhere to be seen in the credits, although all the key personal were Hammer hands – designer Bernard Robinson, cinematographer Arthur Grant, supervising editor James Needs, even production manager, art director and wardrobe were the usual Hammer people. But for various business reasons, the film was officially a production of BHP Films, a company formed by producer Jon Penington, writer George Baxt and agent Richard Hatton.

Baxt was an American who had a few notable low-budget horrors to his credit – Sidney Hayers’ Circus of Horrors, John Llewellyn Moxey’s The City of the Dead (both 1960), Hayers’ Burn, Witch, Burn (1964) – and had previously made some uncredited contributions to Hammer’s The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). His script for The Shadow of the Cat was a throwback to the Old Dark House genre which was popular in the 1920s and ’30s, and apparently had proposed to emulate the subtle movies of Val Lewton by leaving the menace unseen, a suggestion which might either be real or just a projection of guilty minds. Gilling, reworking the script, made the title cat for better or worse explicit.

I can’t say whether Baxt’s idea would have resulted in a better movie, but as it eventually turned out, the film is entertaining but fundamentally absurd. Suggesting a grounding in a respectable literary source, it opens with old Ella Venable (Catherine Lacey) up in her attic room reading Poe’s The Raven to her cat Tabatha. The old house creaks and groans, concealing the approach of a figure who beats the old woman to death. This is Andrew the butler (Andrew Crawford), who has committed the crime for his employer, Ella’s husband Walter (Andre Morell). Together with housekeeper Clara (Freda Jackson), Andrew and Walter dispose of the body by burying it in the woods.

Having called the police to report that Ella is missing, Walter summons other members of the family to discuss the disposition of the estate. These are Walter’s greedy brother Edgar (Richard Warner), Edgar’s crass son Jacob (William Lucas) and Jacob’s wife Louise (Vanda Godsell). Finally, there’s Ella’s favourite niece Beth (Barbara Shelley, in her second role for Hammer following The Camp on Blood Island [1958]). Walter’s scheme was designed to overturn Ella’s plan to leave everything to Beth and it’s crucial that he and his allies find the will which disinherits them all. Beth has just one ally of her own, reporter Michael Latimer (Conrad Phillips), who suspects Walter of foul play.

All of this is pretty standard for an Old Dark House mystery. But into the mix is added Tabatha, the only witness to the murder, who prowls the house and gradually knocks off everyone involved in her mistress’s death. Or rather, she prompts them all to do themselves in, her mere presence provoking such paroxysms of guilt that they behave in increasingly ludicrous ways, their escalating paranoia essentially pointing to their guilt like a big flashing neon sign. Although the cast is excellent, their rapid and extreme derangement becomes comic rather than evoking the psychological horror which was no doubt intended.

The turn-of-the-century production design and Grant’s shadow-filled photography create an effective atmosphere of menace and the cast are all fully committed, but as often happens in movies which try to use cats as a vector for horror, Tabatha seems rather cuddly and adorable. Perhaps a snaggle-toothed alley cat would have worked better than the plump tabby cast in the role … or perhaps if it had remained a mere shadow, suggesting a projection of guilty minds (as Baxt had intended), it might have avoided inadvertent comedy.

The most surprising thing about this minor entertainment is that the effective score was written by the great Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis, who would become widely known to filmgoers a few years later with his scores for Zorba the Greek (1964), Z (1969), Serpico (1973) and others. He had previously scored a couple of Michael Powell movies and just the year before had provided music for another film produced by Jon Penington (Faces in the Dark, dir. David Eady).

*

Nightmare (Freddie Francis, 1964)

Freddie Francis had established himself as one of England’s foremost cinematographers by the time he turned to directing in the early ’60s. Having been an operator on films by Michael Powell, John Huston and Carol Reed, he became a director of photography in the mid-’50s, winning an Oscar for Jack Cardiff’s Sons and Lovers (1961). Perhaps strangely, having been involved in numerous prestige productions in that capacity, his directing career consists chiefly of lower-budget horror movies – a genre he had no real passion for. Having shot one film for Hammer (Cyril Frankel’s Never Take Sweets from a Stranger [1960]), Francis was hired by the studio to direct one of Jimmy Sangster’s “mini-Hitchcocks”, Paranoiac (1963); pleased with the results, they immediately hired him again for a follow-up.

Although Sangster had been key to Hammer’s reinvention as an internationally successful purveyor of Gothic horror, having written The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), and a number of subsequent films in the genre, he wasn’t particularly keen on them. In the wake of the success of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), he turned to writing contemporary psychological horror scripts (although, as he acknowledged, these were more influenced by Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques [1955] than by Hitchcock). Having shopped the first of these around to various producers, he wound up back at Hammer. Taste of Fear (Seth Holt, 1961) initiated a new strand in contrast to the Gothic movies – contemporary stories shot in black-and-white and centred on psychological derangement rather than physical horror.

Nightmare (1964) was the fourth of these, made in quick succession, and it already shows signs of self-parody with its overly convoluted plot and overwrought performances. Typical of the type, it hinges on an elaborate plot to make a female character believe she is going insane (in this, the genre goes even farther back than Les diaboliques, to Patrick Hamilton’s play Gaslight, adapted for film in 1940 and 1944); the underlying motive for these schemes is almost always financial, getting someone out of the way to secure an inheritance. This is true of Nightmare.

Janet (Jennie Linden in her first feature) has been on the edge since witnessing her mother kill her father on her eleventh birthday. She lives in fear of inheriting her mother’s madness, a fear which produces terrible dreams which make her wake up screaming in her boarding school dormitory. After a particularly bad incident, the school decides to send her home, accompanied by a sympathetic teacher named Mary (Brenda Bruce). Janet is eager to get home because she has a crush on her guardian, Henry Baxter (David Knight), but she’s disappointed to find that he’s not there to greet her. Instead, he has arranged for a companion, Grace (Moira Redmond), to keep an eye on her.

Also in the house are the housekeeper Mrs. Gibbs (Irene Richmond) and chauffeur John (George A. Cooper), who are concerned about Janet’s unstable state of mind. But despite Janet’s precarious condition, she’s repeatedly left alone to be visited by the mysterious, spectral figure of a woman in white with a scarred face (Clytie Jessop) who leads Janet to her parents’ bedroom where the woman is found lying across the bed with a knife stuck in her chest. One of the script’s problems is that this is repeated several times, each time leaving Janet collapsed in hysterics as it takes a surprisingly long time for anyone to respond to her screams.

The most unexpected aspect of the narrative, no doubt influenced by Psycho, is the abrupt removal of Janet (a conscious reference to the star of Hitchcock’s movie?) from the film, although up to the mid-point she is clearly the story’s protagonist. Almost catatonic with fear and paranoia, she’s introduced to Baxter’s wife who, not surprisingly, is the spitting image of the woman in white. Janet stabs her to death in front of everyone and is hauled off to the same asylum where her mother has been imprisoned for years, never to be seen again.

The story abruptly shifts to Baxter and Grace, who quickly marry after the obstacle of his wife has been handily removed. Bringing Janet back to the house and staging those spectral encounters was designed to transform the girl into a murder weapon which would divert all attention away from the scheming couple, enabling Baxter to take complete control of the family fortune.

But something isn’t right. Grace and Baxter’s relationship is immediately threatened by a series of small incidents – a woman phoning for Baxter, whom he denies knowing; the barman at the inn they’re staying in who recognizes Baxter from a visit a few weeks earlier with a different woman… Grace begins to have doubts and is upset when he insists they go to live at the house where they staged the murder. Before long, Grace is seeing a mysterious woman wandering the halls and she becomes convinced that Baxter is now trying to get rid of her… This repetition suggests that women in general are susceptible to delusion and hysteria, their grip on reality precarious at best, and prone to outbursts of murderous violence.

The shift in focus from Janet to Grace and the repetition of the gaslighting tactics designed to push them both into madness and murder may be conceptually interesting, but in the event it tends to keep the viewer at a distance, perhaps interested in the mechanics but not really emotionally engaged. The final revelation ends up feeling perfunctory and anticlimactic.

And yet, as is generally the case with Hammer movies, production values are good despite the relatively low budget and as always the cast is full of talented character actors if not the studio’s more recognizable stars. Although credited to John Wilcox, a talented cinematographer himself, it seems evident that Freddie Francis had a hand in the photography as well as directing; the bleak winter exteriors and shadowy interiors reflect the work he had done for other directors and the look of the movie almost compensates for the weaknesses of Sangster’s script.

*

Captain Clegg (Peter Graham Scott, 1962)

Before their success with Gothic horror, Hammer tried their hand with a number of other genres, including comedy, mysteries, science fiction and historical adventures. The first of the latter was a Robin Hood feature directed by Val Guest in 1954, The Men of Sherwood Forest. It wasn’t a big success and the studio didn’t return to the genre until after the mid-’50s Quatermass adaptations and later Gothics had made a name for the company and firmly established their box office success. From 1959, with The Stranglers of Bombay, to 1967 and A Challenge for Robin Hood, they produced nine more, many of them leaning towards the graphic horror for which Hammer had become known. Among the imperial adventures (Stranglers, The Brigand of Kandahar) and English history (The Scarlet Blade), the studio made three low-budget pirate movies which managed to work around the seemingly serious limitation of not being able to shoot at sea on a ship. With the judicious use of some stock footage and, in the case of Don Sharp’s excellent The Devil-Ship Pirates, a full-size mock-up which didn’t need to set sail, the ingenuity of Jimmy Sangster’s scripts and Bernard Robinson’s art department effectively concealed the lack of sea-going action.

Made between Terence Fisher’s The Pirates of Blood River (1961) and Sharp’s The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964), Captain Clegg (1962) opens with a very brief prologue in which a ship is glimpsed in the distance, but then settles for an English village and a river with a couple of rowboats. In the prologue, the unseen pirate captain condemns one of his men who attempted to rape Clegg’s wife; the man has his ears slit and his tongue cut out before being stranded on an island. Years later, that man reappears, a prisoner of the King’s excise man Captain Collier (Patrick Allen), who arrives in the Kentish village of Dymchurch which is perched on the edge of Romney Marsh, a coastal area of woods, streams and swamp which is used as cover by a band of smugglers.

The entire village is in on the smuggling, prospering under the leadership of the local parson, Dr. Blyss (Peter Cushing), whom it’s not a surprise to discover is none other than the infamous Captain Clegg. Despite the brutality of the prologue and the state of the man in Collier’s custody – treated like an animal being used to sniff out the smugglers – Blyss proves to be something like the story’s hero, using the skills he learned during his years of committing crimes at sea to raise the village out of poverty. Back in England, it’s the King’s men who are the villains, preying on ordinary people, determined to squeeze revenue out of those with little money. The battle of wits between Blyss and Collier leads inevitably to betrayal and violence.

As usual with Hammer, the cast is full of fine character actors – Michael Ripper, David Lodge, Milton Reid, Martin Benson, Jack MacGowran – with Cushing obviously relishing the opportunity to play a kind of hero for once and Allen a strong antagonist, while Oliver Reed and Yvonne Romain are sufficiently engaging as the requisite romantic couple. The work of director Peter Graham Scott is serviceable, but the film seems to reflect his experience as a television director; though the locations are quite striking, the visual style is rather flat.

The oddest thing about Captain Clegg is that it half-heartedly tries to conceal its origins while yet hiding them in plain sight. Producer John Temple-Smith had proposed to Hammer in 1960 that the studio remake the 1937 Gainsborough adventure Dr. Syn (dir. Roy William Neill), which had been based on the novels of Russell Thorndike about a former pirate-turned-vicar who leads a band of smugglers. The studio bought the remake rights, but at the same time Disney had bought the rights to Thorndike’s books (eventually making a three-part TV adaptation called The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh [1963], cut down to feature-length for theatrical release as Dr. Syn, Alias the Scarecrow). Hammer’s film bears no credit to Thorndike, but essentially only changes one character name – Syn becomes Blyss – while retaining many other details: the setting of Dymchurch and Romney Marsh, the name of the parson’s right-hand man, Mipps (Michael Ripper), and many details of the story.

*

The Phantom of the Opera (Terence Fisher, 1962)

By 1962, Hammer had revived in lurid colour all the classic Universal monsters – Frankenstein, Dracula, the Mummy, the Werewolf – so it was time at last to get around to the earliest of Universal’s horrors. The studio had gone all out with their lavish 1925 adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera, building huge sets and shooting sequences in colour. The production was troubled and Rupert Julian’s direction rather clunky, but one crucial thing made the movie a lasting success: the casting of Lon Chaney in the title role. His extreme (and painful) makeup created an indelible pop-culture image of body horror which by itself compensates for many of the film’s shortcomings.

Universal remade the movie in 1943, with Claude Rains as the Phantom and Arthur Lubin directing; that version highlights some of the problems with the property as a horror story. Disfigurement and murder vie with classy high culture (the opera itself) and much emphasis was placed on the romance between Susanna Foster as Christine and Nelson Eddy as Anatole, who loves her and poses a threat to the Phantom as an object of her affections. The melodramatic story is more romance than monster and the supposed villain’s motive is simply to train a young ingenue’s voice so that it’s worthy of his music.

Although the story provides some set-pieces which can be milked for dramatic impact – particularly the famous unveiling of the deformed face and the dropping of the theatre’s gigantic chandelier – it’s closer in essence to something like Compton Bennett’s The Seventh Veil (1945) or Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948), the story of a demanding teacher who pushes a female student to the limits of endurance as he tries to mould her into his own image of artistic perfection. This is a far cry from vampires, werewolves and the living dead.

Hammer actually pushed the story even farther from monstrosity, originally developing it as a possible vehicle for Cary Grant, who had apparently expressed an interest in starring in one of the studio’s productions. Even though Grant vanished during development, producer Anthony Hinds’ script (written under his usual John Elder pseudonym) diminished the horror even more by making the Phantom a tragically romantic figure, while assigning a few murders to a newly invented character, a mute hunchback who saves the Phantom’s life and devotes himself to protecting his “master”.

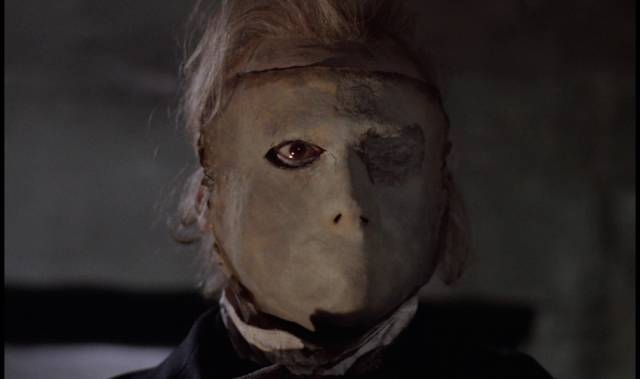

Terence Fisher was, not surprisingly, given the directing assignment and he took to the project as something of an escape from the Gothic horrors of which he was never particularly fond. A romantic by nature, The Phantom of the Opera (1962) brought out Fisher’s strengths; the film is authentically romantic, the strange triangle of Phantom (Herbert Lom), Christine (Heather Sears) and theatre producer Harry Hunter (Edward de Souza) providing an emotional core, while Hinds invents an excellent new villain in the form of corrupt Lord Ambrose d’Arcy (Michael Gough), who cheats timid composer Professor Petrie and presents Petrie’s music as his own. Enraged, the Professor is severely disfigured when he furiously tries to destroy the stolen music at the printer’s; scarred by acid, he jumps into the Thames and is washed into the sewers where the hunchback (Ian Wilson) finds and revives him.

This backstory is revealed later, of course, the early stages taken up with the production of the new opera claimed by d’Arcy as his own work. The obnoxiously predatory Lord continually interferes with the production, concerned only with self-aggrandizement and extorting sexual favours from the lead singer. Initially the role of Joan of Arc is performed by Maria (Liane Aukin), but she’s scared off by the spectral Phantom. During auditions for her replacement, young Christine is found in the chorus, impressing Harry and the theatre’s manager, Lattimer (Thorley Walters), who immediately want to cast her. d’Arcy, finding her to his liking, agrees, although he insists that she requires private voice tutoring from him … at night, in his private apartments.

When Harry steps in to save her from what would no doubt have been rape, d’Arcy is furious and fires them both. Needless to say, the Phantom is unhappy with this turn and has his henchman kidnap Christine for lessons in his sewer lair while causing problems for the theatre – threats, a couple of killings to intimidate d’Arcy into rehiring Christine. There is an obvious parallel between the Phantom’s and d’Arcy’s motives – both claim an interest in helping Christine to refine and develop her voice, but one is sincere while the other has unsavoury ulterior motives. Professor Petrie may be hideously scarred, but the smooth, manipulative d’Arcy is monstrous to the core.

Strangely, although Fisher has sustained an atmosphere of doomed romance and potential violence for much of the film, the final stretch is fumbled, almost as if he were wilfully suppressing the more blatantly horrific elements. When the Phantom confronts d’Arcy, the latter rips off the mask, but Fisher deprives us of the sight which horrifies the villain, who flees in terror, never to be seen again. So not only do we not see what has been concealed, we are also deprived of a satisfying come-uppance for the villain who has earned our hatred. Only in the final moments, as the chandelier is about to fall on the triumphant Christine, does the Phantom tear off his own mask before fatally jumping in to push her out of the way – giving us a very brief glimpse of Professor Petrie’s scarred face. It’s a throwaway moment, devoid of dramatic impact, a begrudging nod to the audience’s natural desire to know what has been hidden.

Despite this short-circuiting of the story’s few opportunities for crass horror, The Phantom of the Opera is actually one of Fisher’s best-directed movies. The limited resources available work in its favour, reducing the spectacle which dominated the original film (and, of course, the later stage musical) and keeping the narrative to a human scale. This is greatly aided by a fine cast, with Gough, Lom and Heather Sears all doing some of their best work. Even de Souza fares well in what could easily have been the thankless role of bland hero; he plays it with charm and humour, giving weight to his relationship with Christine. While Lom as the Phantom is driven by a kind of madness, the mid-point flashback which fills in his story humanizes him and elicits sympathy, his climactic sacrifice redeeming his more questionable actions as the Opera Ghost.

The Phantom of the Opera has never been a favourite of mine in any of its iterations and to be honest, I had always considered Fisher’s film dull until I first saw it on Blu-ray in 2017, when my opinion began to change – watching it again, my personal revisionism continues, and I was surprised to find myself liking it quite a lot. In retrospect, I wish I had been more aware of it when I met Heather Sears while working on Dune in 1983 – she was married to production designer Tony Masters and spent some time in Mexico during the shoot; I would have loved to chat with her about Hammer and Terence Fisher.

*

As with Indicator’s previous Hammer box sets, the presentation of each movie is impeccable (though the hi-def transfer of Captain Clegg does reveal the weaknesses of the effects used to create the “marsh phantoms” which scare off anyone who gets too close to the smugglers’ activities, and there is noticeable distortion in the Cinemascope image of Nightmare). Phantom is provided in three different versions, the theatrical feature in both 1.66:1 and 1.85:1, plus the extended TV cut which runs an extra fifteen minutes, presented in open-matte SD. The extras are too numerous to mention in detail. Each feature gets an introduction from Kim Newman and a commentary (two in the case of Phantom); there are interviews with various cast and crew members, retrospective featurettes on each production, analysis of each film’s score by David Huckvale, a lengthy audio interview with Freddie Francis and a startlingly long (201 minutes!) video interview with Peter Graham Scott. Each film also gets a substantial booklet with an essay, interviews, excerpts from contemporary reviews and selections from British and American promotional materials.

Comments